If you believe his fund-raising appeals John Cornyn is worried. In an August email, Texas’ senior senator claimed that for the first time his reelection campaign may not meet its money goal by the end of the month. Things were so bleak that Karl Rove himself—via info@johncornyn.com—reached out in an email a few days later to tell me and many thousands of others that some “old friends”—identified as “loyal patriots, everyone”—had stepped up to match any donation dollar for dollar. “Senator Cornyn is running out of time,” Rove warned, “and if he fails to meet his goal, it will give dangerous momentum for his opponents.”

That kind of borderline panicky language was also apparent in July, when Republican party chairman James Dickey thanked Cornyn and almost the entire Texas GOP congressional delegation for turning out in force at a Republican Party of Texas fundraiser. Dickey said the event “underscores the urgency we all feel in Texas to come together and dig in for an election fight next year that we haven’t seen in decades in Texas. There are real threats to our majorities in Texas because of the 2018 election.”

Really? Are the Texas Republicans actually running scared, or are they just scaring supporters into reaching deeper into their wallets? According to the latest campaign finance reports, Cornyn’s campaign had $9 million in the bank for his reelection bid and had raised more than $2.5 million in the previous quarter alone. Compare that to MJ Hegar, the Air Force veteran who is one of seven Democrats challenging Cornyn. As of July, she had raised a measly $1 million during the same period. All the gnashing of teeth and rending of garments seems a little … hyperbolic.

In fact, since Cornyn first ran for office in 2002, challenging him has seemed like an errand for only the foolish or hapless. If you were a Republican, what wasn’t to like about the heir to Phil Gramm’s Senate seat? Cornyn practically radiated the once-admired characteristics of moderation and reasonableness—he was so moderate and reasonable, in fact, that President George W. Bush considered him for the U.S. Supreme Court to replace either Sandra Day O’Connor or William Rehnquist.

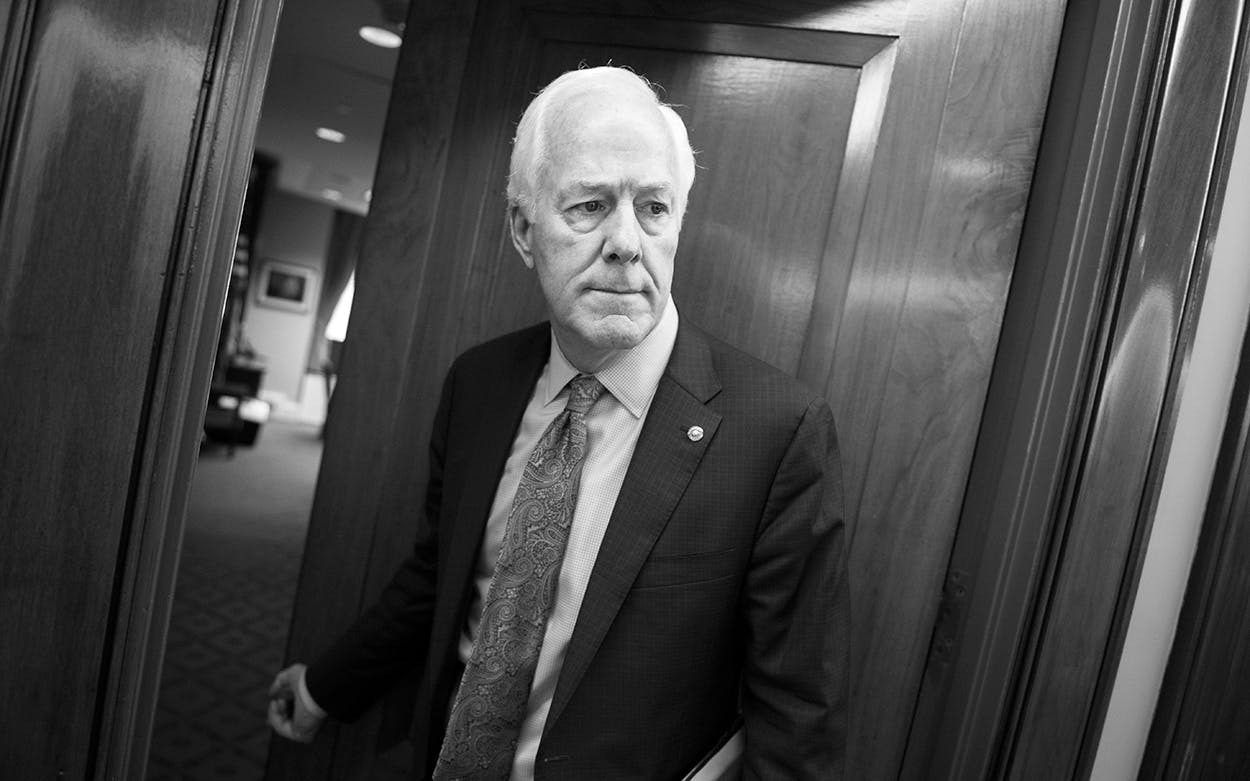

When he last ran for reelection, in 2014, Cornyn raised $14 million and trounced all comers. (Okay, yes, his primary opponent was Congressman Steve Stockman, who is now serving ten years in federal prison for committing more than 23 felonies. His sacrificial Democratic opponent was David Alameel. Cornyn beat him 61-34.) Compared to the junior senator from Texas, Ted “Voldemort” Cruz, he was well-liked, known to play well with others—at least with other Republicans. And damned if he didn’t just look the part, too. White-haired and square-jawed, Cornyn offered a courtly face to represent Mitch McConnell and Donald Trump’s more outrageous policies.

So to most people—including many Texas Democrats—Cornyn’s run for reelection in 2020 seemed like just another sure thing, one last ride before the 67-year-old hung up his spurs and started raking it in as a lobbyist or a rainmaker for some big-deal law firm. Cornyn is certainly still the favorite at this point in the race, but in the last few months, his invincibility has come to look, well, less sure. In fact, a few things have happened that might be responsible for turning fat-cat Republicans into fraidy-cat Republicans.

The first shock came with Beto O’Rourke’s surprisingly narrow loss to Cruz in 2018. And then the polls started rolling in. In February, a Quinnipiac poll showed that voters actually liked Cruz better than Cornyn—51 to 43 percent. This September, another Quinnipiac survey showed that 23 percent of Texas voters said they would definitely consider voting for Cornyn, while 35 percent said they definitely would not. Thirty percent were leaning toward supporting him, while 13 percent were still undecided. You could almost hear the huhs among ambitious Democrats.

Unlike Cruz, Cornyn has a squishy base. Cornyn started out as a Bush Republican, but as time passed and politics changed, he tacked right and then further right like virtually all Texas Republicans. But perhaps Cornyn wasn’t convincing enough as he shifted: Despite his Trumpian voting record, he’s drawn a tea party opponent in the primary. State senator Pat Fallon, of Prosper, is hitting Cornyn in the same way some of the Democratic presidential candidates are attacking front-runner Joe Biden: “What would happen in Texas if we can finally have a candidate—a new one—that energized the right?” Fallon said in a speech on September 9, before announcing he was exploring a run. “That gave everybody in this room something to believe in.”

Fallon is probably not much of a threat, but Cornyn’s fealty to President Trump, which probably looked like a good idea early on, might create other problems. Half of all Texans are not fans of the president, according to most polling. If you are a Republican, maybe you are okay with the border wall, but perhaps those family separations make it hard to sleep at night. Maybe you’re worried about labor shortages that Trump’s anti-immigration policies could create in your business. And what about the trade policies that threaten to cut into profits generated in ports from Laredo to Houston?

Then there is the gun issue, which is also starting to make some Republicans (even Dan Patrick!) rethink their stance. For anyone who needs a reminder why, Texas has been the scene of four mass shootings in less than two years. The killing of 22 people in El Paso, with Latinos specifically targeted, has the potential to become a major campaign issue. The same September Quinnipiac poll that showed Cornyn slipping also showed some shifts on gun control: 53 percent of Texas voters support tougher gun laws. Cornyn has made a lot of noise about background checks and the like, but so far most of what he has proposed has remained just that: noise. Asked about stricter gun laws after El Paso, Cornyn replied, “I would say there is no simple answer,” and went on to blame “people who are twisted” for mass shootings.

Of course, a vulnerable Cornyn is still different from a defeated Cornyn. Democrats will almost certainly look to O’Rourke’s near-victory for lessons. After all, it’s the only thing close to a win for Texas Democrats in a quarter-century. Was it right or wrong to seek out new voters instead of maintaining the traditional focus on crossovers and independents? Should a Democratic candidate focus on rural votes when the cities are—and will continue to be—the Democratic strongholds? Should one run as a staunch progressive or a moderate?

As it stands today, the best thing on the Cornyn campaign horizon is the lack of a major, well-funded Democratic opponent. In contrast to the Cruz/O’Rourke race, this field is larger and far more diverse, with no obvious stars. (Of course, people have already forgotten that Beto was far from celestial when he announced his candidacy. People thought he was nuts for thinking he had any shot at all.) Air Force veteran MJ Hegar has the most support in the race so far, according to the most recent Texas Tribune/UT poll, though more than half of those polled hadn’t formed an opinion on the field. No one else even gets into the double-digit range.

Chris Bell, a former congressman and perennial candidate, checks the (probably hopeless) white male liberal box. Royce West, an accomplished African American state senator from Dallas who has served since 1993, is also in the running, as is Amanda Edwards, a Harvard-educated Houston city councilwoman who has made a name for herself by pushing to speed up Hurricane Harvey aid to those who need it most. (Edwards is also African American.) Then there is Cristina Tzintzún Ramirez, a progressive community organizer who was the cofounder of the Workers Defense Project and a founder of Jolt, a Latino political group.

If Texas is shading blue, the outcome of this crowded primary could tell us a little bit about what kind of blue the state will be—moderate or progressive, standard-issue Democrat or someone from the grassroots. According to Bob Stein, a professor of political science at Rice University and a longtime pollster, the Democratic base is growing and the Republican one is shrinking, but not much else is certain.

Some of Cornyn’s opponents see the path to victory coming through imitating Beto’s near-success, while others are carrying out a return to business as usual—ditching any kind of progressive notions to command the middle ground. Conventional wisdom suggests that a moderate like Hegar, who lost to deeply conservative incumbent Congressman John Carter in 2018 by just 3 percent, would be the strongest candidate against Cornyn. Amanda Edwards takes essentially the same moderate tack: she defined herself to me as a “coalition builder…a candidate for people in the middle who feel like they are without a home”—in other words, the traditional Democratic base.

But progressives like Tzintzún Ramirez see a different calculus in O’Rourke’s numbers: instead of trying to win over aging whites and crossover moderates, the right approach is to energize new voters among the young, people of color, and the poor: “The idea that you can win in Texas by running to the middle is why Democrats have consistently lost,” says Ramirez.

It’s worth noting that the Cornyn campaign has already taken aim at Royce West. The commercials that ran during the August Democratic debates damned West as a liberal who pals around with the likes of Wendy Davis and Chuck Schumer. The Texas Tribune’s Ross Ramsey pointed out that Cornyn’s dumping on West was similar to Governor Abbott’s attacks on Lupe Valdez. The criticism raised her profile, and she then went on to beat the (probably) more viable Andrew White in the 2018 gubernatorial primary. The general was a relatively predictable rout, 56-42.

Other factors will certainly affect the Senate race: the elimination of straight-ticket voting, the identity of the Democratic presidential nominee, and, in turn, how much energy and cash the national political organizations spend here. And then there is President Trump, who was not on the ticket in 2018 but probably will be in 2020—with all the baggage and benefits that entails. As one Austin gadfly put it, “This year, everyone is at risk.”

This story has been updated to reflect that Chris Bell served in the U.S. House, not the Texas House.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- John Cornyn