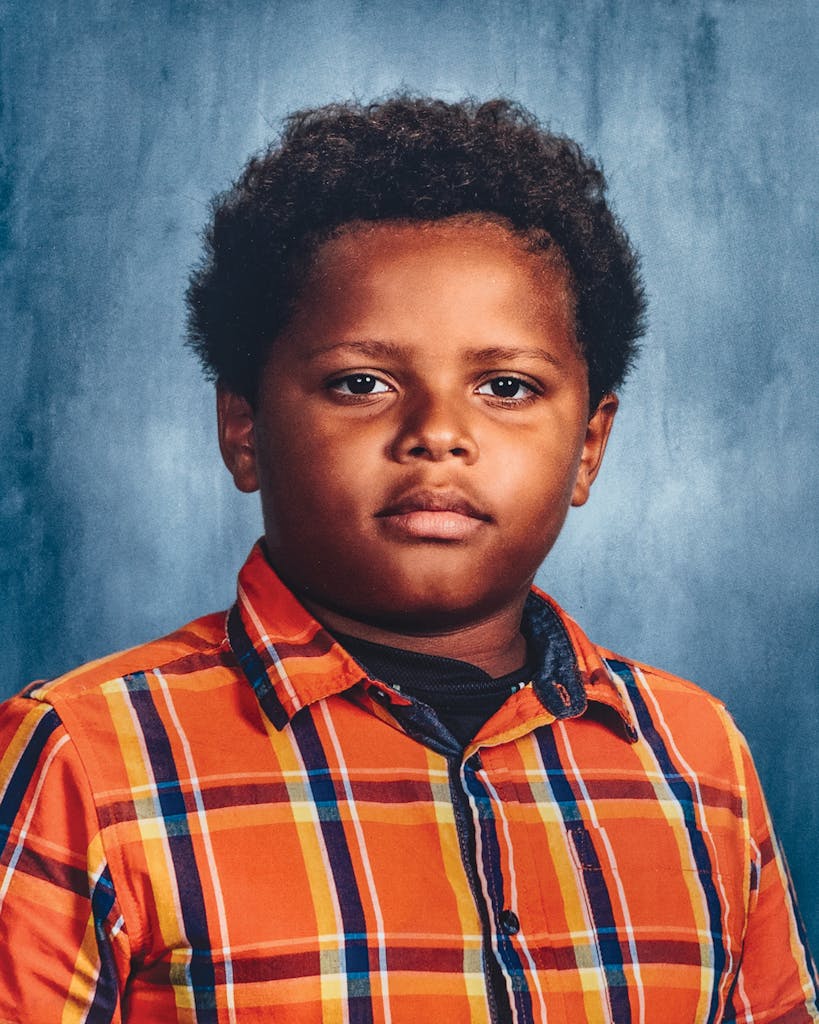

In the beginning, the ailment seemed to be little more than an ordinary cold with a low-grade fever. Out of caution, Amber McDaniel kept her ten-year-old son, Zyrin Foots, home from school. Zyrin plopped down on his family’s big, brown living-room recliner, watched TV, and waited for the sluggishness and congestion to pass. But three days later, McDaniel began to grow concerned. Though Zyrin was normally quick to bounce back from illness, his condition didn’t seem to be improving. He was still just as lethargic as he’d been days earlier. Even more worrying was his breathing, which had tightened to a shallow wheeze.

On a Thursday evening in late September, as Zyrin’s breath became more labored and his legs began to ache, McDaniel decided she’d seen enough and asked her mother and father to take them to a clinic in Huntsville. After they arrived, the clinic called an ambulance that took Zyrin to nearby Memorial Hospital. There, Zyrin went into sudden cardiac arrest. A few days earlier, the carefree little boy had been riding his bike through his neighborhood in Huntsville, an East Texas town of 46,000 about an hour north of Houston, and talking about Halloween costumes with his little brother, Zaiden. Now McDaniel found herself watching doctors perform chest compressions on her son and praying that his heart monitor would start beeping again. The suddenness of it all—the way a child could be healthy one week but on the verge of death the next—was hard to comprehend. Even so, McDaniel remained hopeful. “Zyrin is my firstborn, and he’s a lot like me; he’s stubborn and he’s a fighter,” she told me several weeks later. “So, when his heart started beating again, I just knew he was going to be okay. And for a little while, he was.”

Despite temporarily stabilizing, Zyrin was rushed to Texas Children’s Hospital The Woodlands, where he tested positive for COVID-19, and then to Texas Children’s in Houston, where he survived open-heart surgery after suffering a second heart attack. Doctors placed him on life support in hopes that his body would begin to recover. The opposite occurred. Weakened by the coronavirus, Zyrin had contracted respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and later developed a rare condition called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), which causes various parts of the body, such as the heart, lungs, and brain, to become inflamed. There have been more than five thousand cases of MIS-C across the country since the pandemic began, but doctors are still trying to understand how exactly COVID-19 is triggering the condition. (McDaniel said her son had no preexisting conditions that might have made him more susceptible to these complications.) With Zyrin’s heart damaged and unable to pump blood, his appendages became gangrenous, with the tissue on his arms and legs turning black and eventually dying.

As her son’s state worsened, McDaniel tried to remain optimistic. She never thought Zyrin would succumb to the coronavirus, she said, in part because two other family members, her father and her nephew, had easily recovered after contracting it. She said she’d tried to have her boys vaccinated in the spring but was told that they were too young. McDaniel chose not to get the shots herself. “I wasn’t super concerned about COVID before Zyrin got sick,” she said. “As far as I knew, most people who got infected recovered just fine.”

Almost as soon as Zyrin had arrived at Texas Children’s in Houston, McDaniel had begun using her iPhone to take photos of her son from different angles. She took hundreds of them, she estimates. Some of the images she showed me zero in on his face, still soft and healthy-looking even as the rest of his body is at battle. Other, more distressing images document that battle at close range, focusing on the gangrene’s purplish-black hue as it marches from Zyrin’s toes and fingers toward his thighs and forearms, consuming his body gradually, inch by precious inch.

McDaniel didn’t snap the photos to say goodbye or to come to terms with his morbid predicament. Instead, she took them because some part of her remained convinced Zyrin was going to live. “I wanted to show him how horrible things had gotten during the time he was in the hospital, to show him what he’d survived,” she said.

But about ten days after Zyrin’s hospitalization, doctors presented McDaniel with an excruciating choice: she could take her son off life support, allowing him to die, or she could give doctors permission to amputate his right arm and both of his legs. His left arm would be left intact but likely unusable because of multiple strokes he’d endured. After undergoing these procedures, McDaniel said, the doctors estimated the child would have a 25 percent chance of survival. Assuming he did make it through the surgeries, Zyrin wouldn’t be able to wear prosthetic legs—the procedures would leave too little of his thighs intact. They gave her a couple of days to make her decision.

Refusing to leave her son’s hospital room, McDaniel consulted with friends and family by phone, processing her choices out loud. But as she lay on a small couch each night, she realized that only she could make sense of what seemed an impossible dilemma. Her son was a few feet away, his eighty-pound body wrapped in plastic tubes that cut into his abdomen and poured from his mouth. He was unconscious, his face innocent and peaceful, but his body was losing its fight.

She thought about how Zyrin had been independent for his age—the result, family members believed, of being the eldest sibling in a single-parent household. A fan of video games and cooking shows, he was active and energetic, a kid his mom had nicknamed Chef Boyardee, for his culinary skill. He’d learned how to prepare French toast from scratch. “He was going to be the next Emeril Lagasse,” McDaniel said. “He had the raw talent.”

In photos, Zaiden and Zyrin look inseparable, their faces lit up with smiles and their arms draped across each other’s shoulders. McDaniel kept picturing Zyrin waking up and realizing he could no longer walk, feed himself, or go to the restroom on his own. There would be no more riding bikes with Zaiden, no more happy-go-lucky adventures, but instead years of painful surgeries, intermittent hospital stays, and constant uncertainty. “I kept wondering if he’d thank me for keeping him alive or if he’d hate me for making him suffer for the rest of his life,” McDaniel told me. “I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t want to say goodbye to my child or give up on him, but I also didn’t want him to experience more trauma. I kept hoping for God to make some miracle happen so it wasn’t in my hands.”

“I kept wondering if he’d thank me for keeping him alive,” McDaniel recalled, “or if he’d hate me for making him suffer the rest of his life.”

Her indecision was amplified by her own experience with physical trauma—trauma that, like her son’s, had come into her life one day without warning and changed everything that followed. It was a February evening in 2013, family members recalled, and McDaniel, then 26, was five and a half months pregnant with a third child. She had just left a Walmart in Conroe, a town thirty miles from Huntsville where she was then living with her two sons and their father, pushing a grocery cart full of snack food to satisfy her pregnancy cravings. As she crossed a nearby street on her way home, she was struck by a truck traveling at high speed. The driver, who left the scene but later returned, was never charged, and to this day, details of the accident remain foggy for McDaniel. She remembers briefly regaining consciousness in a patch of grass beside the road, her body broken, bloody, and surrounded by first responders. She spent the next four months in an induced coma. “The doctors later told me that if I wasn’t pregnant when the truck hit me, then I wouldn’t be alive,” McDaniel said. “They said the baby protected some of my vital organs, but of course, I lost my child.”

The impact shattered her legs, punctured both her lungs, and nearly destroyed her liver, which required seven surgeries to heal fully. For months, her meals were delivered through a feeding tube. The accident cost her the use of her right hand, and for years, she was unable to walk without assistance. The injuries, which she and her sister say generated more than $1 million in medical bills, also forced her to stop working as a door-to-door vacuum-cleaner salesperson, a job she’d grown to love. Almost a decade later, she remains on disability but has stopped taking pain medication and has regained her ability to walk without a cane. While the wreck left her right leg shorter than her left, she makes a point of walking everywhere she goes. “She walks to Walmart and H-E-B, and she walks the boys to school every day, and she’s been doing it that way for years,” said Ashley Engmann, McDaniel’s older sister. “It’s her way of refusing to let her disability define her.”

When I visited McDaniel in late October at her home, a small, one-story brick residence in a Huntsville neighborhood devoted to low-income residents, she showed me a calendar on which she awards herself a tiny star each time she completes physical therapy exercises. Over time, her dedication has yielded significant results. After training herself to become left-handed, she has nearly regained complete use of her formerly dominant right hand. She has become accustomed to fighting for incremental improvements in her quality of life, some of them years in the making. As she debated whether to take Zyrin off life support, she envisioned him trying to do the same, only without any viable appendages to rehabilitate.

The most difficult call in Pastor Philip A. Hagans II’s career arrived on October 12. The 41-year-old preacher at Huntsville’s Unity of Faith Missionary Baptist Church had led funerals and counseled grieving families before, but this situation was different. On the other end of the line, McDaniel wanted to know if he could offer any guidance. Considering what was at stake, Hagans knew he didn’t want to influence McDaniel’s decision. Instead, he asked God to give him the right words for the moment. “She was leaning toward letting her little boy go peacefully,” Hagans recalled. “My only words to her were ‘I’m going to support whatever decision you make, and do not feel bad because I know—and God knows—you’re doing the best you can for your son.’ ” Hagans added, “That was basically all I could say. This was the most difficult decision any parent could have to make.”

Hagans was a Zyrin fan. He’d first met the boy about a year earlier, when Zyrin and his brother had ridden up to the airy, white-steepled church on their bikes, walked inside, and asked if they could start attending the Sunday service. From that point on, the boys became regulars, attending more consistently than many adults. Though McDaniel describes him as more reserved than his younger brother, the Zyrin who walked into Hagans’ church, at least, was a talker. Sitting in the pastor’s office, he opened up about kids at school giving him a hard time, about stress at home, and about the upwellings of anger that had begun to occur without warning, sometimes as soon as he woke up in the morning. Family members told me the anger had several origins, one of the most obvious being taunting from classmates. McDaniel said she didn’t know why exactly he was targeted. “Zyrin was a very sweet kid and a very handsome kid, and I saw other kids pick on him for no reason,” she said. “I think it was jealousy, because I couldn’t figure out any other reason for them to be mean to him.”

The other source of tension in Zyrin’s life involved his father, McDaniel’s ex-boyfriend, who had been incarcerated in 2019. While she declined to share details of the troubles the man had caused, McDaniel said his arrest came as a blessing. “Zaiden, my other son, said we really started to live life once my ex went to jail,” she said. When Zyrin found Hagans, McDaniel was thrilled that her son had a trustworthy male figure to open up to, an adult who didn’t also happen to be his mother. The minister wasn’t surprised by the boy’s frustrations. At only ten years old, Zyrin had already witnessed his mother’s medical struggles, and while his father’s absence was in one way a relief, he now felt pressure to care for both his mother and his little brother—challenges, Hagans told himself, with which most adults would struggle to cope.

Together, the pastor and the preteen talked about video games, cooking, growing up, and the Bible. Hagans taught Zyrin to pray and, when angry, to observe his feelings while he counted down from the number ten. Despite Zyrin’s challenges, Hagans was struck by the boy’s uninhibited ability to tap into joy. Whereas most kids would play on their phones or sleep during services, Zyrin would sit in the front row and engage with the sermon. “He would stand up and wave his hands and clap with the music,” Hagans said. “The atmosphere seemed like it was making a difference in his life.”

Soon after she spoke with Hagans, McDaniel made up her mind. She told family members that she would spare her son another invasive surgery and the years of fraught health that were certain to follow. They would have a short time to say goodbye to Zyrin before doctors removed him from life support. One by one, masked family members were allowed to make brief visits to the hospital room. Some prayed over him; others spoke to the little boy one last time, telling him how much they loved him. Engmann, his aunt, got permission to escort Zaiden into the room; he’d been too scared to go in by himself. “It was just a horrible feeling, because I think all of us felt like Zyrin wasn’t supposed to be there,” she said. “Until he took his last breath, I don’t think my sister fully believed that he wasn’t coming home at some point.” Zyrin was pronounced dead on October 13 at 5:03 p.m., sixteen days after he’d started feeling ill.

When he saw his brother in the casket, Zaiden insisted on placing his finger beneath Zyrin’s nose to make sure he wasn’t breathing.

When I asked how she’d decided to let him go, McDaniel said that a single expression, one only a mother would recognize, had given her the answer she was looking for. “He was unconscious, but he had this look of anguish on his face that I hadn’t seen since he was an infant,” she said. “At that moment, I knew he was in too much pain to continue.”

A few days after Zyrin’s death, Hagans, a father of four boys who range from seven to seventeen years old, told me he was struggling with it, not just because he was sad but also because he was frustrated. Huntsville had always been the kind of place, he said, where people looked out for one another. But that same thoughtfulness didn’t seem to extend to concerns about COVID-19, even though Walker County has experienced more than 10,000 cases and lost 185 residents to the virus. Some folks in Huntsville were still not masking around vulnerable neighbors and relatives. Others, he said, were sending kids to school with COVID-19 symptoms because it was more convenient than keeping them at home. Hagans couldn’t understand it. “I chose to keep my kids home when they tested positive for COVID, and yes, it interrupted my schedule and my wife’s schedule,” Hagans said. “But I’d rather do that than allow them to get someone else sick whose body can’t bounce back, and they end up losing their life like Zyrin—all because I didn’t want to miss work? That’s a disgrace.”

At press time, more than 220,000 Texas students had tested positive for COVID-19 in the 2021–2022 school year. Of the state’s roughly 72,000 reported COVID-19 fatalities as of November 19, 35 were younger than ten years old and 77 were between ten and nineteen, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services. Zyrin’s family members think he may have contracted COVID-19 at school, though that can’t be confirmed.

I first reached McDaniel by phone about a week after Zyrin’s death, late on a school night, and asked her to tell me about her son. Midway through our talk, Zaiden, who was sitting nearby, grabbed his mother’s phone and began to tell me about his older brother’s favorite color (bright orange) as well as his favorite animal (the tiger). That night, he was in the process of writing a eulogy to read at Zyrin’s funeral two days later, though he was already feeling some stage fright. Despite the nerves, he assured me, he planned to push past his discomfort. “I want everyone in the church to know that he was a great brother to me and that he would always make me have a good day or find a way to make me smile,” Zaiden said. “I already miss him.” Then he handed the phone back to his mother and disappeared into his bedroom.

A few days later, when he saw his brother in the casket, Zyrin’s body clad in a dark suit and an orange tie and his face unblemished, Zaiden insisted on placing his finger beneath Zyrin’s nose to make sure he wasn’t breathing, Eng-mann told me. “He needed to be certain his best friend wasn’t really there, that this was all real,” she said. “He just couldn’t believe that Zyrin wasn’t going to get up and come home.”

McDaniel said she’d been trying to stay strong for Zaiden, who was “devastated,” and had been unable to begin her own grieving process. Instead, she’d been compartmentalizing her agony to keep it from overwhelming her. Drawing upon skills she’d developed after the hit-and-run that nearly killed her, she said her plan was to move forward hour by hour, focusing on the next task at hand. When I asked her what she wanted others to know about her son, she paused, seeming to hold back tears. “I wish I could put it into words,” she finally said. “He was such an awesome little guy. He was going to be an amazing man.”

A few minutes after we hung up, McDaniel called back. This time, her voice trembled with some barely containable mixture of exhaustion and heartbreak. “I thought Zyrin was going to beat it, because I died too, but I’m still alive,” she said. “And he, well, he was just like me.”

This story appeared in the January 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “One Mother’s Nightmare.” An abbreviated version originally published online on November 1, 2021. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Health

- Longreads

- Huntsville