This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On the first weekend in March 1986 Ed McBirney, a Dallas savings and loan magnate, organized a junket to Las Vegas for fifty of his institution’s closest friends and customers. A dark, slim, square-jawed 33-year-old, McBirney was known as the financial wizard who had forged Sunbelt Savings from six disparate savings and loans and in less than four years increased its assets more than 5200 per cent. McBirney also had a reputation as a party animal. In Dallas he frequently threw lavish theme parties and every spring arranged other trips for Sunbelt’s friends—to Hawaii and to Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, for fishing and, of course, to Las Vegas for gambling. McBirney was no stranger to Caesar’s Palace, the Stardust, and the Dunes; he had lines of credit at two of them.

But this Las Vegas trip was the most outrageous jaunt of all. The guests flew on a borrowed 727, and they checked into luxurious rooms at the Dunes. Some of the travelers contributed to an entertainment fund. The entertainment arrived one evening later in the trip at a cocktail party in McBirney’s spacious suite. Four women came into the room and began a striptease act. Once disrobed, they proceeded to perform sexual acts on some of the businessmen. For some, it would be the most memorable extravaganza in a long string of Sunbelt excesses. But for McBirney, it would be his last bash.

Just four months later Edwin T. McBirney resigned as chairman of Sunbelt Savings. Current Sunbelt officials say that $190 million of its real estate portfolio is “real estate owned,” or REO, an accounting euphemism for investments that have soured so badly the institution has had to repossess the property. REOs are not unique to Sunbelt. They are the ghosts of the golden age of real estate in Dallas. REOs haunt the landscape in the form of empty buildings, unleased shopping centers, partially occupied apartment complexes, and overvalued land—follies financed in large part in the early eighties by savings and loans, institutions high on the rush of OPEOM, the cynic’s rubric for Other People’s Money.

Sunbelt, like a lot of savings and loans, emerged from the golden age crippled rather than prosperous. McBirney left Sunbelt loaded with bad loans on its books. He, and many other go-for-broke entrepreneurs like him, indulged in their own rules for making quick profits. Many lenders chose to ignore the reality of real estate investments. Instead of research and rationale, greed often fueled their decisions. They avoided the arduous number crunching that was necessary to predict the long-term viability of a project and cavalierly executed transactions, expecting the market to bail them out later. They funded “flips” that artificially inflated the value of land, and they used the easily made dividends to support their high standard of living. The billions of dollars they sank into bad real estate projects drove out good projects, causing grievous distortions in the market. And when the real estate market began to deteriorate, the savings and loans’ owners worked together to disguise their actions from federal investigators.

Now Dallas is in the midst of what one developer calls a real estate depression, and the savings and loan system of the entire Southwest is strained. In March Governor Bill Clements declared that Texas S&Ls were in a state of crisis. Clements described the problem as “extremely complicated” and said that he would name a task force to study it. Even a brief study of the problem shows how complicated it is. The president of the Federal Home Loan Bank, which regulates savings and loans, has said that more than forty Texas institutions are “brain dead”—technically insolvent or broke. Figures recently released by the bank show that Texas as a whole lost $462 million in February alone. Another 104 savings and loans institutions had dipped below the level normally considered healthy.

Some thrifts have been affected by the hobbled economy, but federal regulators say many also have been crippled by bad management. Since 1985, ten savings and loans in Texas were placed under management consignment orders—decrees made by state and federal regulators for management changes at troubled thrifts. The orders began appearing when funds at the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), which insures savings and loans deposits of up to $100,000, became so depleted that regulators could not afford to close any more ailing institutions. The orders save the FSLIC from liquidating an institution, which would force the FSLIC to pay off the institution’s losses all at once. Instead, the FSLIC engages new management, and the institution is rechartered as a federal savings and loan. For the moment the debilitated thrift is kept alive.

In congressional testimony in March federal regulators said it would cost more than $5 billion to patch up the sick thrifts in the Southwest (other observers say it would cost $40 billion to do the job right). Regulators want $15 billion to recapitalize the FSLIC fund. But Congress has been under intense lobbying from the real estate and thrift industries, which are afraid of the actions that strengthened regulators would take against them. For two months Congress has been fighting over how much new money—first it was $5 billion, then it was $15 billion—to infuse into the FSLIC fund. And as Congress niggles, the situation in Texas does not improve.

An Opportunity for Growth

Thrifts haven’t always been so conspicuous. Historically, savings and loans were in the steady business of savings accounts and home loans—transactions involving relatively small amounts of money, usually within hundreds of thousands of dollars. But the industry started to skid in the late seventies, when regulation restricted the interest rates that S&Ls could pay their depositors and the much higher yields of money market funds became available. Many customers took their money out of the thrifts and put it into the funds, seriously weakening the thrifts. By 1980, however, a gradual lifting of the interest-rate ceiling began, and the institutions started competing with the money market funds that had lured away their deposits. But that created a problem too. The S&Ls had to pay high interest rates to keep their depositors, but on the income side of the ledger, the mortgages they had sold over the years were fixed at low interest rates. That was a money-losing proposition. By July 1982 more than six hundred savings and loans in the country were insolvent.

The Garn–St. Germain Act, which deregulated the thrifts in November 1982, was hailed as one means by which S&Ls could make themselves profitable again. The act allowed thrifts to deal in commercial real estate by lending a developer money on a piece of raw land, and in addition to lending money on the project, the S&L could actually be a part owner in the real estate, something banks are not allowed to do. Thus, a savings and loan could make a loan on a piece of land; earn a profit on the fees, percentage points, and interest associated with the loan; and have a potential profit as a part owner of the property.

Under those conditions, the most aggressive S&Ls expanded their commercial loan portfolios rapidly. Commercial loans involved much larger amounts of money than S&Ls were used to dealing with, and commercial real estate appraisal involved not only the soundness of, say, a building but also the building’s future capacity to generate income in a changing market. Investing in commercial real estate was tricky enough that banks had done it for years with only checkered success. But that didn’t cause some S&Ls to hesitate.

With the prospects of making money on the points of a loan and the possibility of making profits as a partner in the real estate involved in the loan, thrifts had a pretty rosy future in Texas, and especially in Dallas. High occupancy rates in offices, apartments, and retail space in the early eighties meant there was a need for new building, and steady migration into North Texas indicated that the market would remain strong. Dallas’ pervasive can-do attitude propelled the expansion. At a time when oil was no longer running the economic engine of cities such as Houston, it seemed that real estate could fuel new prosperity.

And as if S&Ls weren’t already encouraged enough to get involved in the real estate market, another important change occurred shortly after deregulation that allowed them to lend more than before on real estate. Previously, the S&Ls could lend no more than two thirds of the appraised value of a piece of land. If the property was worth $100, the S&L could lend just $66.66. That meant the borrower had to put some of his own money into the deal or find another source of funds for the remaining one third. As of April 3, 1983, however, S&Ls could begin lending at 100 per cent of the appraised value: they could lend $100 on a piece of land worth $100. It could be a no-risk deal for the borrower, because he wouldn’t have to invest any of his own money. Looking back, one regulator now calls April 3, 1983, “the day the war started.”

Hot Money

It is true that in the early eighties many thrifts were on the brink of disaster. But it is also true, in hindsight, that in their haste to help failing thrifts, regulators and lawmakers did not realize that the situation they had created carried a tremendous potential for abuse. Not only were million-dollar deals made at no risk to the borrower, they were also made at no risk to the S&L: deregulation gave S&L owners the opportunity to make money whether or not the loans they approved were economically productive. Simply put, if investors bought a savings and loan at that time for $3 million, they had the potential to loan $100 million. To attract deposits, they could turn to money brokers who would bring in new funds in the form of $100,000 certificates of deposit. These jumbo CDs, paying higher than the prevailing interest rate, are commonly known as “hot money.” On any given day large investors, pension funds, and even municipalities are shopping the jumbo market for the S&Ls paying premium rates. The S&L pays a price in obtaining brokered funds—a cost the institution must make up in higher profits somewhere else—but once the deposits are on hand, the savings and loan can start making commercial real estate loans.

Some thrifts would routinely charge six percentage points in fees on loans for acquisition, development, and construction. Thus on a loan portfolio of $100 million they could make $6 million in points alone, regardless of how sound an investment it was. Since the owners invested only $3 million in the S&L, they have already made $3 million to pay themselves.

The war that started on April 3, 1983, it turns out, was a battle of risk that left the federal government the most vulnerable. Savings and loans were already one of the most highly leveraged businesses in America. And, under Texas law, the owner of a savings and loan that had the ability to lend $100 million could also form a service corporation through his S&L and borrow $200 million more.

But another side of the business had not been deregulated. The FSLIC still insured deposits, so it would be stuck with working out the problems S&L entrepreneurs might cause. If the savings and loan goes broke, the investors lose only their original $3 million. They have already made $3 million in profits in points. The government must pick up the tab for the remaining $100 million.

“Fast Eddie”

Spurred by the prospects of a deregulated market, Ed McBirney began buying a string of S&Ls from Bonham to Stephenville that were eventually assembled into Sunbelt Savings. Then Sunbelt grew; it acquired mortgage companies that did business in California, Florida, and Georgia. It formed a commercial banking division, and it created a telemarketing division that took phone orders for deposits. Since there are regulatory limitations as to how much an institution can loan on any one project, S&Ls commonly sell pieces of their loans to other thrifts. Sunbelt had a division that did this over the phone.

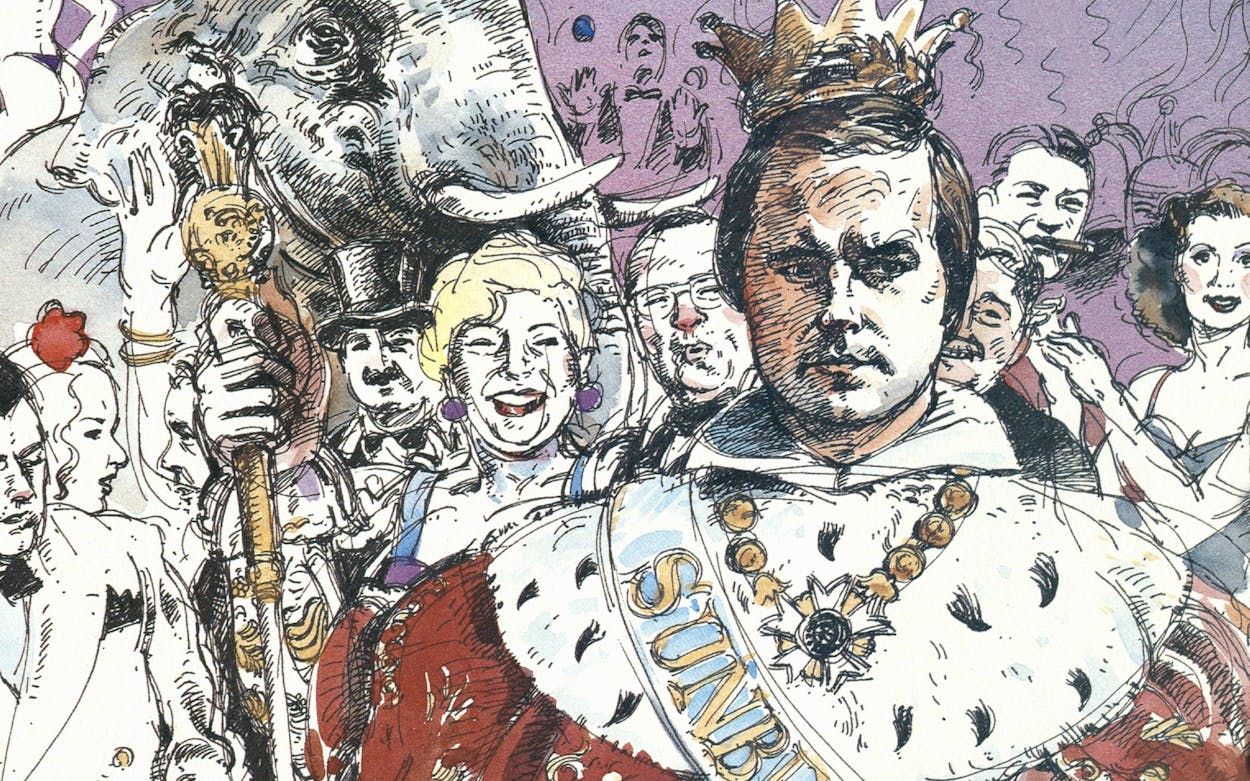

Ed McBirney was at least as visible as his company, and his party-giving added to the luster. On Halloween 1984 hundreds of guests arrived at his palatial North Dallas home to find a feast of lion, antelope, and pheasant. In the back yard smoke machines provided an eerie, supernatural fog. A magician performed feats of levitation, while two huge disco singers, Two Tons of Fun, supplied the dance music. Those who know him say McBirney had two speeds, “on” and “off.” At this party, dressed as a king, he was on. McBirney was pulling in a six-figure income, and his S&L, which had grown into a $1.3 billion institution, was famous for outgunning the competition. It was no wonder that Sunbelt’s nickname was “Gunbelt Savings.”

A young man hired at Sunbelt during this period says he was “scared to death” from the moment he first walked in the door. Although he had extensive experience in the financial industry, he says, “I had never seen loans being made as fast as they were making them.” The office atmosphere was frenetic and unorthodox. Ed McBirney was known as Fast Eddie, a man “so smart that it was frightening,” whose role was to come up with ideas for deals.

McBirney’s reputation as a highflier extended outside Sunbelt’s offices on the LBJ Freeway. He regularly held court at Jason’s, a North Dallas restaurant, where he had a house account and his own table equipped with a phone. He frequently lunched with real estate developers as well as with the executives of other Dallas savings and loans, among them Jarrett Woods of Western Savings, Don Dixon of Vernon Savings, and Tom Gaubert, a principal owner of Independent American Savings. Over lunch and a pricey bottle of Bordeaux, Fast Eddie sketched out his deals: the table was covered with butcher paper, so the evolving facts and figures could be written down. When lunch was over, McBirney sometimes took a piece of the paper with him for future reference. The ideas would then be pitched to a team of lawyers, who would structure them in legal form on paper. A deal was never really a deal until it was “papered,” and McBirney’s lawyers were meticulous in their paperwork. However, McBirney moved so fast and did so many deals that he proved exceedingly difficult to pin down during final negotiations. There is now litigation concerning at least one deal that calls into question the tactics McBirney used while negotiating it.

But in 1984 there was enough prosperity to go around that hard feelings were soon forgotten. By the end of the year, many S&L empires appeared indestructible. To celebrate, McBirney threw a Christmas party at the film studio in Las Colinas. Ben Vereen entertained on a soundstage transformed into a winter wonderland. The theme was, appropriately, “Babes in Toyland,” and guests donated gifts to a children’s charity.

Kissing the Paper

Outsiders coming to Dallas during this period, dazzled by the burgeoning buildings and reflective glass, accepted the growth as the logical extension of a city that had its own soap opera on television every week. For those inside the real estate market, the excitement of the period is often described as similar to that of being in an athletic event every day. The thrill of a done deal, a big real estate commission, or a large profit put adrenaline in the veins. It made deal addicts out of many a young broker and developer.

One of them was Sam Ware, a 22-year-old graduate of Abilene Christian University, who, in just a few years, would become one of Sunbelt’s biggest borrowers. When Ware arrived in Dallas in 1980, he began working for a company that bought apartments and syndicated the ownership of them to investors. “I was a bush-beater,” he says, “in charge of discovering undervalued properties and finding ways to acquire them.” Then, like many of his contemporaries, he decided he could be bush-beating for himself and making more money. In 1983 he formed Dabney Companies.

For young developers like Ware looking for investors, banks were generally out of the question. They required longer track records and more financial wherewithal than many new developers had. With their historical experience in real estate, banks were also cynical about the quality of the deals many young developers brought to the table.

So the new developers went to savings and loans. At first, even S&Ls eyed some of them warily. Their financial statements were not substantial enough to acquire loans on their signature alone. But there was a solution. The institutions would encourage the borrower to find a wealthy, established individual to “kiss the paper.” With a famous name belonging to someone rich on the dotted line, the loan was co-guaranteed and could be approved.

A young developer would pay a price for all of this. He would pay two or three points more on his loan than he might have been charged at a bank. He might pay a higher interest rate than at a bank. He would have to give his co-guarantor a piece of his profits. But the developer would be in business, and the momentum of the market was such that almost any piece of property could be flipped for a profit.

Ware found someone to kiss his paper and accelerated the breadth and size of his activities. Eventually he could start qualifying for loans on his own, and most often he went to Sunbelt Savings. “Not just the lenders were making the money, at that point,” Ware says. “Real estate attorneys were coming in, more title companies, more contractors, more real estate brokers, more homeowners, more office developers, and retail operations. Every facet [of the market] was perking because of the millions of dollars that came in—more speculators, more everything—because people saw tremendous profits in a short period of time.”

Real Estate Night

The profits allowed a sumptuous lifestyle for those lucky enough to make them. The wives of young real estate brokers, still in their twenties, found it possible to hire nannies for their children and to build additions onto their upscale homes. And lest anyone be jaded by Dallas nightlife, there was the Rio Room.

Club developer Shannon Wynne’s new, members-only night spot was nestled at the edge of the Park Cities, Dallas’ most affluent suburbs. The Rio Room was the closest thing that the city had to a speakeasy. Its clientele was a fashion parade of designer suits, expensive jewelry, and even tuxedos on occasion. Patrons threw money around the way Wall Streeters did before the Depression (which in the case of Dallas real estate was just a few months away).

Ed McBirney made the scene. Larry Hagman, Sammy Davis, Jr., and Adnan Khashoggi all came to the Rio. Status seemed important to Rio members, who never numbered more than five hundred. For $500 a Rio member received a silver membership card; for $1000, a gold card. Mere dabblers could walk in for $20. And bar tabs of more than $1000 were not unusual. Louis Roederer Crystal Champagne, at $150 a bottle, was a big seller, as was Dom Pérignon, at $140 a bottle. Waitresses sometimes accepted cocaine in addition to their tips. The Rolex was the watch to wear; the Mercedes=Benz 380 SEC coupe, the car to drive. One entered the club two ways—through a parking lot that was a statement in itself (Rolls-Royces and Ferraris filled the front row, Porsches and Mercedes were lined up behind them) or through a hallway that connected to another of Wynne’s clubs, called Nostromo, which adjoined the Rio Room in the front.

The Rio was small, fifty feet by fifty feet, with a three-dimensional mountain range depicted on one wall and a backlighted mural of sandblasted glass on another. A disc jockey controlled not only the room’s music system but also the lighting behind the mural, which had the effect of regulating the mood of the evening. A one-way mirror in the men’s room offered a view of the dance floor. On many a night, the dancing moved from the floor to the tables. The patrons knew their behavior at the Rio would be kept in strictest confidence. As the evening progressed, the music grew louder and the lights pulsed faster; the 4 a.m. closing time would sometimes arrive before anyone expected it.

On Thursday night—real estate night, as it was called—the mood was electric. The avant-garde of the property business came to swap business cards, celebrate their latest sales, and sometimes do deals. One night a loan was consummated with a handshake, and on another a contract was signed in the men’s room at neighboring Nostromo. One evening a guest, exuberant from a big deal he had signed earlier that day and impaired by the cocktails he had been drinking since noon, proceeded to the parking lot, where he kicked in the door of a Rolls-Royce, just for fun.

Made as Instructed

By the middle of 1985, the party lights were still on in North Texas real estate, enhanced by an abusive practice typical of the golden age: the land flip—real estate vernacular for when a piece of property changes hands rapidly and escalates in price. For such a process to succeed, a network of financial institutions had to work together. One of the biggest real estate deals of the period was a textbook example of the procedure. The property was a collection of more than 1500 acres in south Fort Worth, which eventually became known as the Hulen 1541 Joint Venture. On November 2, 1983, the acreage sold for $17 million on a note from First City Investments. One day later it sold for $24 million on a note from State Savings of Lubbock. Thirteen months later on a note from Stockton Savings the property sold for $32 million. Finally, on December 26, 1985, the acreage sold for $50 million. It roughly tripled in price in just over two years. The final loan on the parcel was made by Jarrett Woods at Western Savings.

An appraisal done by Richard Hewitt on the land after the sale says it is worth only $21 million. Hewitt is a nationally known appraiser who wrote the guidelines then in effect as the industry standard. In his evaluation Hewitt wrote, “The property has experienced numerous ownership transfers over the past five years examined. Several of these title transfers occurred on the same day or within several days of each other and are likely less than ‘arm’s length’ transactions.”

Other appraisals on the property set its value much higher. The final appraisal of the property, done for Woods at Western, set the value of the property at $58.5 million “as is,” or $85.5 million “as developed.” The development plan calls for some of the land to be used as residential property, however, and at current absorption rates the supply of lots in the parcel will last well over a decade.

“It’s not what a property is worth; it’s what you can get it appraised for” is a real estate maxim. The American Institute of Real Estate Appraisers has rigid qualifications for an appraiser before he or she can be called an MAI (Member, Appraisal Institute). But for many in the real estate business, MAI means “Made as Instructed,” because they believe appraisers tend to value property at what they have been told it will sell for. “When you’ve got a buyer who’s agreed to a specific amount on a parcel and an S&L that’s agreed to lend that amount, it’s hard not to set that value on it,” says one appraiser. In a transaction in which the lender is a third party to the buyer and the seller, the lender can be expected to scrutinize the property. But when a savings and loan is both lending the money and buying the property as a participant in the deal, the S&L is no longer disinterested.

Brokers, developers, and S&Ls have been known to hire different appraisers to look at the same piece of property until they get an evaluation they like. Independent American Savings in Irving actually went so far as to acquire its own commercial company that made appraisals on Independent American’s loans. The transactions may have been at arm’s length; it is simply a question of how long the arm was.

A Dead Horse for a Dead Cow

By autumn of 1985, some saw the market softening. It wasn’t apparent in snowballing foreclosures, which would characterize late 1986 and early 1987, but it was evident in the way savings and loans approached some of their borrowers. Institutions were going to great lengths to keep bad loans off their books. Unlike banks, S&Ls were not required by law to set aside reserves to cover bad loans. With their smaller capital reserve requirement, they had a much lower capacity to absorb loans that weren’t performing. So in order to stay out of trouble with examiners, they found ways to disguise their bad loans. And to make their S&Ls look healthy, they found ways of putting new, cosmetically acceptable loans on their books.

One method of disguise is known as trading a dead horse for a dead cow. Two institutions each have a nonperforming loan. Institution A has a dead horse. Institution B has a dead cow. Institution A creates a new loan on its books for B’s dead cow, while B creates a new loan on its ledgers for the dead horse. They have traded their bad loans, each institution has a new loan on its books, and the loan’s status as a troubled asset is, for the moment, hidden from the federal regulators who inspect the institution’s books.

Another trick is called “cash for trash,” which in its simplest form works like this: A developer approaches an S&L with a loan proposal. He has found a piece of property that he can buy for much less than its appraised value. The S&L agrees to lend on the parcel under the condition that the developer helps take care of a “trash” piece of rental property on its books. So the S&L lends the developer far more than he needs to buy the good property. He agrees to divert some of the extra cash into upgrading the trash property, at no liability to himself. He puts the rest of the extra cash into his pocket. The deal is done. The developer has his parcel of land and money in his pocket. The S&L has repaired its trash loan for the time being, while booking a new loan. A new loan means revenue in points, fees, and interest; dividends for the S&L’s owners; and the potential to make more loans. The trouble was, as S&Ls slipped closer to financial ruin, they took more and more risks on their good loans in hopes that points and profits would bail them out of their bad ones. In time, some would become desperate.

The Need for a Jet Fleet and 84 Rolls-Royces

Nevertheless, by Halloween of 1985, Ed McBirney appeared to be prospering more than ever. His Halloween bash featured the Spinners, and the warehouse where the party was held was decked out like a jungle. There were water buffalo ribs for appetizers and a live elephant for decoration. For entertainment a magician made the elephant disappear. Clad in a pith helmet and khakis, McBirney presided with binoculars hung from his neck.

McBirney and other S&L wild guys didn’t limit their fun to parties. As their institutions grew, so did the perks of some savings and loan executives. A number of them decided they had a need for corporate aircraft. Sunbelt, through one of its subsidiaries, purchased two jets—a Gulfstream II, the Cadillac of executive planes, and a Falcon 10. McBirney used the Gulfstream to fly to Las Vegas, where Sunbelt had acquired a mortgage company. Sunbelt also had a Beechcraft King Air and a Bonanza.

But the largest jet fleet was maintained by Vernon Savings. Owner Don Dixon, a Dallas builder and developer who had bought his hometown S&L in Vernon, sixty miles west of Wichita Falls, and had set up a Dallas branch, outdistanced his rivals by amassing a collection of six aircraft. Three baby-blue jets topped the list. The largest, a Falcon 50 jet, which looks like a small replica of a Boeing 727, was followed by a Learjet and a Cessna Citation. A twin-engine Cessna and a Beechcraft King Air were also registered to Vernon. And where other institutions needed only fixed-wing aircraft, Vernon needed a helicopter. It bought a seven-passenger Agusta 109. Dixon, whose beard, gold chains, and open shirt gave him the look of Kenny Rogers, also kept a staff of five full-time pilots, who often were called upon at odd hours to fly the aircraft.

There were excesses in terms of business deals too. At Sunbelt, the Gunbelt reputation of shooting from the hip lived on. Three days before Thanksgiving of 1985, Dallas luxury-car dealer and Sunbelt client Bob Roethlisberger landed in a private jet at Rancho Rajneesh, Oregon. The ranch was home to the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and Roethlisberger had come to the remote desert community to buy more than seventy cars from the Bhagwan’s Rolls-Royce collection. It would be a difficult deal to finance, because the final sticker price for that many exotic cars would run into the millions. Selling the cars would be equally difficult once they were purchased; 36 of them had been painted by one of the Bhagwan’s staff artists, designed with peacocks and geese in flight and decorated with two-toned metal flake and cotton bolls. That many luxury cars painted in that way would be hard for any market to digest. But Roethlisberger bought 84, and the deal was financed with a note of more than $3 million from a wholly-owned subsidiary of Sunbelt Savings.

Steady Decline

Back in Dallas, by Christmastime, much of the real estate community had become decidedly edgy. Evidence was surfacing that the Dallas market was overbuilt. If McBirney was concerned, it wasn’t visible at his Christmas party. A furniture warehouse in North Dallas was decorated in a Russian-winter theme. Waiters dressed as Russian peasants strolled among the guests, making sure no one went hungry. Blintzes were prepared to order. A live bear was one diversion, and the Manhattan Transfer was another. McBirney’s cohost for the party was one of his biggest clients, Sam Ware, who had borrowed $50 million from Sunbelt.

But that party was the last hurrah for Ware. Just a few weeks later, early in 1986, Ware was forced to restructure many of his loans. Since then, his business has been in a steady decline. Today, at age 29, he estimates that he has borrowed about $300 million on real estate in the short four-year life of his company. But in the last eighteen months, he has had to reduce the size of his firm by 65 per cent. He looks older than someone approaching thirty. His six-one frame shows the effects of too many long hours and too little exercise. There are deep circles under his eyes. He says he has taken a few “seven-digit hits” in the market decline.

Many young developers who got off to a grand start in the golden age share Ware’s fate. But Ware differs from them because he is willing to talk about the past and admits that he and others made mistakes. “There was more capital available to do anything with than there’s ever been before,” he says. “The faults the lenders made, I believe, are that some projects should not have been invested in. I believe that certain people who borrowed money should not have been allowed to borrow as much money as they possibly did, and I think the supervision of borrowers was probably not as tightly reined as it should have been. Everyone knew the music would stop. I hope that people were not that naive to think that it wouldn’t.”

When the Music Stopped

In 1986 the silence of deals not being made was deafening. As the market cooled, borrowers fell behind on their payments and S&L balance sheets began to bleed red. Federal regulators focused greater scrutiny on savings and loans’ real estate lendings. Developers, without money, were unable to flip property.

Early on it looked as if the biggest loser stuck at the end of the land-flip chain would be Jarrett Woods at Western Savings. In the middle of 1985 Woods had been the last lender in the Carrollton 80 Joint Venture flips, a $17 million project-eighty acres north of Dallas of unzoned, unincorporated land without road access—that ultimately would be posted for foreclosure. He ended 1985 with a loan on the Hulen 1541 Joint Venture, south of Fort Worth, which, before 1986 ended, was in bankruptcy. Those are just two loans in a much larger portfolio. Records show that Western continued to lend heavily into 1986, after other lenders had drastically curtailed their lending activity. According to Roddy Reports, which are compilations of statistics for North Texas commercial real estate, Western loaned $175 million in Dallas, Tarrant, and Collin counties in 1986. As early as March 1986, however, Woods and other directors of Western may have felt that trouble was coming. They paid a Dallas law firm $500,000 to defend against a possible shutdown of the S&L by federal regulators and put another $1 million in an escrow account for the same purpose.

But the defense tactic didn’t work. On September 12, 1986, federal regulators closed Western Savings. It reopened the next Monday as Western Federal Savings. Jarrett Woods, the majority stockholder of Western Savings, had fought the closure, saying that the regulators had devalued the net worth of the institution without informing him. By the time it closed, Western had grown more than 5700 per cent in less than four years. Regulators said Western used high-cost brokered funds to fuel its growth. Several months later, in congressional testimony, federal regulators described the actions of a Texas savings and loan executive who collected more than $3 million in salary, bonuses, and dividends while his institution went into the red. They later identified that institution as Western Savings.

On March 20 of this year, federal regulators assumed control of Vernon Savings, naming a new president and board of directors. By December 1986 Vernon had grown 1600 per cent in less than four years. Federal regulators said that 96 per cent of the institution’s $1.3 billion in loans was more than sixty days overdue. They said Vernon made many loans based on faulty appraisals or no appraisals at all. Parts of those loans were sold to savings and loans in other cities and states that will now suffer the consequences. Don Dixon, who held 91 per cent of Vernon’s stock, had left the institution a few months earlier. Before the federal takeover, regulators said Dixon had collected more than $8 million in salary, bonuses, and dividends during his tenure. Now federal regulators are charging Dixon and six other former Vernon officers with looting the institution. A civil suit filed in Dallas federal court seeks more than $380 million in damages.

S&L owners say many of their problems were brought on by the mistakes of the regulators. The biggest regulatory blunder, they say, occurred at the end of 1984, when an edict came from Washington that net-worth requirements for thrifts would be raised as of January 1, 1985. That meant that instead of having $3 in reserve for every $100 on deposit, thrifts would have to start setting aside more, so that by 1990 they would have to have as much as $6 in reserve for every $100 in loans. A certain amount would need to be set aside every quarter, and if the institution grew, even more would need to be saved. At the same time, S&Ls would have to start setting aside money as reserves for possible bad loans. From a regulatory standpoint, these draconian measures were mandated by the failing health of the $900 billion thrift industry.

But the way some thrifts see it, this requirement made things worse, because it tempted a few institutions into making even riskier-than-normal loans on the long-shot chance of raising their net worth. Now, some of the long shots and quick-profit loans are on S&L books as REOs. That property, in the form of empty buildings, is a sore spot for developers who did not do business with savings and loans in the golden age.

“The S&Ls just didn’t do a lot of basic research,” says one of those developers. “They’d fund a shopping center on an empty corner and think they were pretty smart. But three other S&Ls would be lending on the other three corners. Now we’ve got a shopping center on each of the four corners. I did my research and built one where there wasn’t any competition. But I’m affected by the glut of space the S&Ls built somewhere else. What do I do?”

The Party’s Over

Dallas now has office space to last eight years; that’s more than enough to fill nineteen InterFirst Plazas, whose 72 stories make it the tallest building downtown. S&L money didn’t build all the offices in Dallas in the last four years, but it built a good share. It built a bigger share of apartments and retail space, which are also in oversupply. In March $951 million worth of commercial property was posted for foreclosure in Dallas County, according to Roddy Reports. That included 19 office buildings, 60 pieces of raw land, and 86 apartment complexes.

When Ed McBirney resigned at Sunbelt, he was replaced by Thomas Wageman, who came from First National Bank of Midland, where he took over after that bank’s failure in 1983. Wageman is not a Texan. In a thick Chicago accent he speaks from experience with the energy crash in West Texas and what he calls the total break of the real estate market: “Our confidence has been shaken. Maybe that’s useful. Maybe it needed to be shaken. Maybe we were too full of ourselves. Maybe we showed off more than we should—humility has never been a strong point for us. We’ve got that pain now.”

In January the Rio Room closed its doors. Before it folded, it became known as the REO room to its most celebrated clientele. On a recent evening at Pasha, a dark-wood-and-polished-brass members-only club that is much more subdued than the Rio, McBirney was seen sitting by himself, staring at the floor. It must have been one of his off times—with characteristic brio, he has started a new company called Tangent.

A federal grand jury in Dallas has subpoenaed the financial records of three hundred S&L executives, real estate developers, and brokers who did deals with one hundred savings and loans in Texas. The FBI has brought extra agents into North Texas for what a spokesman describes as “one of the largest S&L investigations in history.” But many in Dallas real estate say the industry is climbing out of the hole. Developers are now working as consultants to S&L regulators, helping them manage the REOs they have acquired as they have taken over savings and loans. And one broker sees the bright side: “If I get a call from a company wanting to move down here, I’m all ready for them. You want an office building? How big do you want it? What color do you want?”

Byron Harris is a reporter for WFAA-TV in Dallas.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas