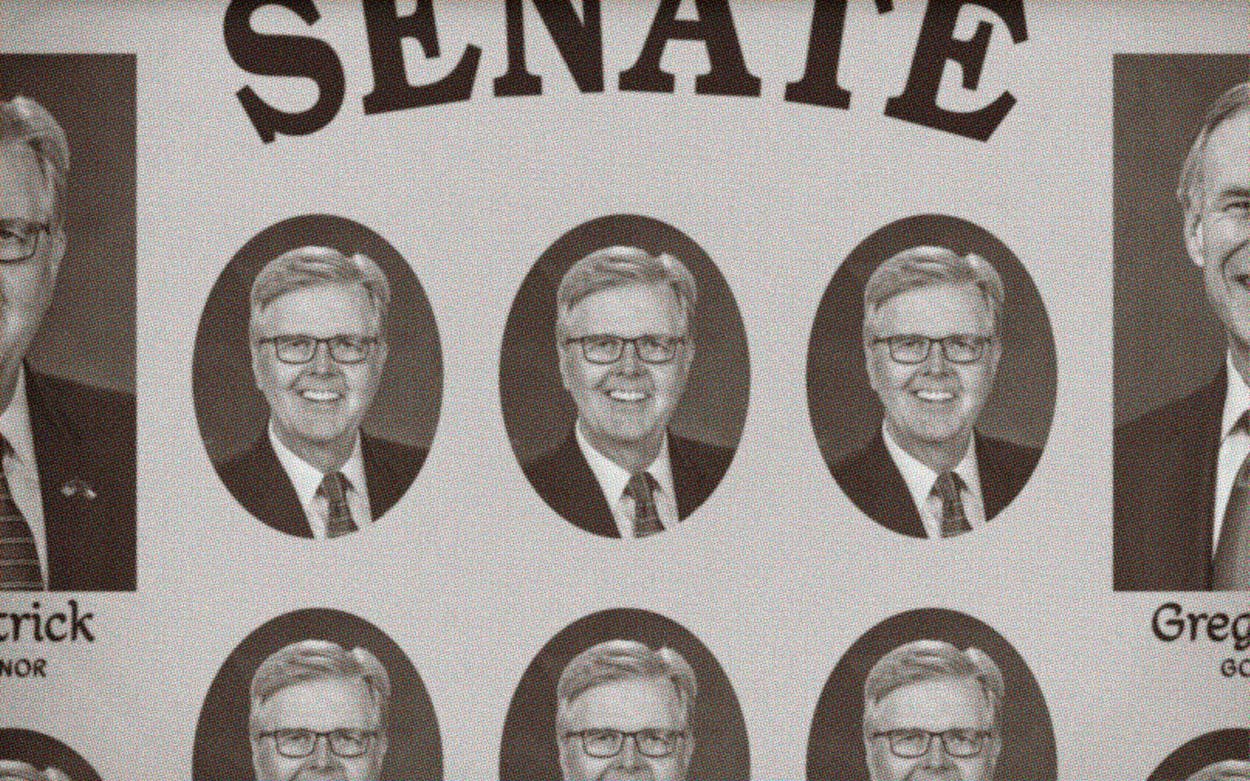

Gather round, my friends, to hear true stories about the knights of the rectangular tables, the misshapen band of 31 adventurers we call the Texas Senate. Today we consider news from Charles Schwertner, Republican state senator from Georgetown, and King Dan Patrick, the benevolent ruler who inspires senators to feats both great and small, hand in hand with his ageless wizard (adviser Allen Blakemore). How does Patrick mete out justice to his sometimes wayward warriors—and what does it say about his plans?

Consider the following tale. On Thursday Patrick, flanked by nine senators of both parties, held a press conference at the Capitol to tout a package of bills that he said would restructure the electricity market in Texas and prevent another failure of the electric grid. With his introductory remarks, he gave Schwertner, the head of the Senate Committee on Business and Commerce and his handpicked subordinate on the effort, a big bear hug. Patrick said he was “so proud” of the bills that Schwertner had produced after “days and months of study,” adding that he was “really proud of their effort” before stepping aside and pushing his courtier into the spotlight.

The hearing was fairly rote stuff, but it was notable for Patrick’s strong vote of confidence in the senator, who got into some trouble earlier in the session. In a not-so-great feat, knight errant Schwertner was arrested for suspicion of driving while intoxicated early in February, after having been pulled over in the early morning hours just past closing time for bars in Austin. The arresting officer noted he had “bloodshot, glassy, watery eyes, was confused, and had slurred speech patterns,” which is not all too different from the way many lawmakers look and act while sober. Later that day Schwertner copped to making “a mistake” and retained the services of fancy Austin lawyer Perry Minton.

Drunk driving is unfortunately pretty common business at the Lege, which sees a host of substance use–related arrests and misbehavior every session. A noble senator getting booked is more notable than the same thing happening to a lowly representative, but it’s much less scandalous than, say, a lawmaker dropping an official envelope filled with cocaine at the Austin airport. And Schwertner had the good sense to be “polite” and “cooperative,” according to the police report. After news of the incident broke, Patrick’s response was terse. Drunk driving is very bad, he said, but added, “I will await the final outcome of this issue in court before making any further statement on the matter.”

This is a very gentle statement, for a few reasons. Schwertner looks likely to get gentle treatment from the court. Heck, he didn’t even have to post bail before getting out of jail—an irony, given he sponsored a 2021 bill to limit the circumstances under which defendants could be released without posting bond. If Schwertner resolved the matter quietly, Patrick seemed to be saying, perhaps by winning deferred prosecution, he would handle it quietly too. And indeed he has.

This is not Schwertner’s first big “whoopsie” in recent years. In late 2018, in the run-up to the legislative session, the senator stood accused of sending lewd texts and at least one picture of his senatorial junk to a University of Texas student with whom he had been corresponding. “This is Charles,” someone with Schwertner’s phone number texted. “Send a pic?” Perhaps most perversely, the person attempted to continue the sexting on LinkedIn. (Schwertner said that someone else with access to his phone had sent the texts, but he did not identify the individual to UT investigators or otherwise cooperate fully. The investigators determined it was “plausible” a third party had sent the messages and did not find that Schwertner had violated school policy.) Patrick took a wait-and-see approach then, too. Schwertner gave up his chairmanship of the Senate’s Committee on Health and Human Services in 2019. But he was allowed the conceit that he was yielding it voluntarily. He won a new chairmanship in 2021, signaling that he was back in the fold.

The light touch with which Schwertner was treated, then and now, stands in stark contrast to the way Patrick has litigated other disputes in the Senate in recent years. In 2019, Patrick stripped state senator Kel Seliger, from Amarillo, who had a justified reputation for independence of thought and action, of a high-profile chairmanship of the Higher Education Committee, in favor of a lower-profile one on Agriculture. Shortly thereafter, Seliger got in a public sparring match with Patrick aide Sherry Sylvester over the slight. During a radio interview, Seliger accused Sylvester of disingenuously framing some statements he made about the drama, and then said, “I have a recommendation for Miss Sylvester and her lips and my back end.”

This was among the tamest gibes that have ever been delivered at the Texas Capitol. But Patrick came down like a hammer. He accused Seliger of making a “lewd comment” about a “female staffer” that “shocked everyone.” Patrick portrayed Seliger as, essentially, a sexual harasser, and gave him a 48-hour ultimatum to apologize for his “unimaginable” actions. Patrick stripped Seliger of his second, lesser chairmanship, and relations between the two men remained in the toilet until Seliger retired last year.

Why was Seliger’s misdemeanor worthy of a death sentence while Schwertner has repeatedly gotten a pass? Simple: Patrick has stressed time and time again that he brooks no dissent in the Senate, and that he values obeisance above all else. Seliger was not a reliable vote for Patrick’s priorities. In 2017, he voted against both Patrick’s proposed property tax regimen and his school choice initiative. Schwertner was more pliable, and his subsequent scandals increased his dependence on Patrick’s favor, surely making him more pliable yet.

Leaders in legislative bodies are generally not proud fathers and mothers there to build up the confidence and résumés of their backbenchers: they’re there to keep them in line. The more members mess up, the more they depend on leadership’s favor. Though it would not be ideal for Patrick if every Republican senator racked up a DWI this session, he would surely prefer getting those panicked calls from the Travis County lockup to having a room full of Seligers looking back at him with eyebrows askew. This is not an approach to leadership that engenders trust and love. For Patrick, it has often seemed, begrudging respect for his authority is enough.

Speak to even like-minded GOP Senate staffers, and the picture that emerges of Patrick is of a relentless micromanager who is loathe to let any slight pass unnoticed. It’s his way or the highway. To admirers, he’s the boss. To others, he’s a tyrant. Either way, Patrick’s power over the chamber is a terrific accomplishment. When he came to the Senate in 2007, relatively late in life at 56, he was a comic figure, a right-wing radio shock jock turned fringe lawmaker with almost no power or influence who was treated with open contempt by his colleagues. Had he lost his 2014 bid for lieutenant governor, he might still be on the fringe. But he won.

Patrick consolidated power soon after coming to office by eliminating the Senate’s decades-old two-thirds rule, which required supermajority support to bring a bill to the floor for debate. That rule had effectively empowered Democrats to block the more extreme parts of the majority’s agenda. After Democrats won a few more seats in 2018 and 2020, Patrick changed the rule again to require even fewer votes to advance a bill. Over the last eight years, his control over the chamber has only increased, as mouthy independents such as Seliger have hit the dusty trail and been replaced by young know-nothings who were elected with Patrick’s help.

Only 4 of the 31 current senators have served longer than Patrick has. “He’s the most powerful figure ever to have held the post,” says lobbyist Bill Miller, who has been watching lieutenant governors wheel and deal since 1985. Miller says it’s a lot simpler to lobby the Senate now than ever before. If Patrick wants a bill passed, it passes. If he doesn’t, it doesn’t. Approach a senator about a bill, Miller says, and the “first question out of the box is, ‘How does the lieutenant governor feel about it?’ ” One time, Miller said, by way of example, he convinced a senator to hold up a bill in his committee, effectively killing it. But Patrick wanted the bill alive. So he simply plucked the bill out of the senator’s hands and gave it to another committee, where it passed without incident.

A body that until fairly recently could have been described as a den of cats—ones who were a bit too pleased with themselves, to be honest—has been transformed into a family of mostly loyal lapdogs. The few Republican senators who occasionally chafe under the enlightened absolutism of Lieutenant Dan had long comforted themselves with the knowledge that Patrick’s current term, ending in early 2027, would be his last. “That’ll be time,” Patrick said in July 2020. “I’m kind of a term-limits guy.” But in January, Patrick made his most significant announcement of the session: he would run again. “I really love what I do,” he said. “I’m in good health, and I just won by eight hundred and thirty-some thousand votes, so why wouldn’t I come back?” He now seeks to extend his tenure to 2031, when he will be eighty.

That could mean, remarkably, that we’re only at the halfway point of Patrick’s tenure as lieutenant governor. The only question now is if senators stay as docile as they have been. At least a handful of Republicans in the chamber surely hoped to run for lieutenant governor in 2026, but the king has cruelly dashed their dreams. There’s no hint of a budding revolt now, to be sure. But eight years is a long time in the Capitol, as it was in Camelot. Lancelot was loyal to King Arthur, too, until he wasn’t.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Texas Legislature

- Dan Patrick

- Georgetown