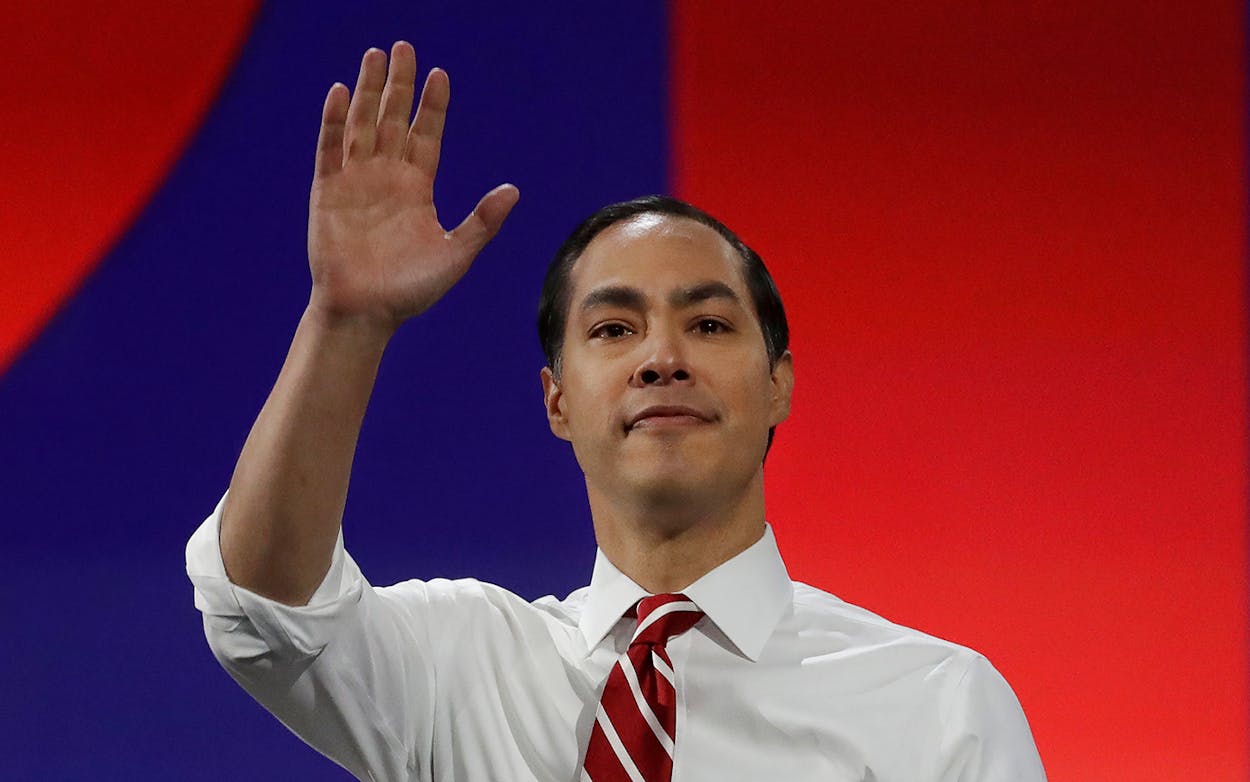

When you spend a great deal of time covering a politician, you learn which buttons you can push to set him off. For Julián Castro, it was asking him about the widespread criticism that he’s too cautious in his political decision making. Fairly or not, the notion was commonly leveled at him when he decided not to make a run for governor or the U.S. Senate in 2018. It’s a critique that extended to his brother, Joaquin, who decided against a Senate bid against incumbent John Cornyn this year. The familiar refrain about each of the Castros became, “No tiene huevos. He has no balls.”

Yet in his efforts to become the forty-sixth president of the United States, a national campaign that lasted ten days shy of one year, Julian Castro defied these critics. He demonstrated political courage by speaking ill of his own party’s nomination process and by speaking boldly on behalf of the underserved, including victims of racial profiling, indigenous people, animals, and migrants seeking new lives in our country.

“We helped shape the debate,” he told Rachel Maddow on her MSNBC show Thursday evening, some twelve hours after he’d released a video announcing he was suspending his campaign because “it simply isn’t our time.”

He launched his bid last January in his hometown of San Antonio, just two days after President Trump had traveled to Texas to make a show of decrying an “invasion” of our country by migrants from the south. The bilingual nature of Castro’s official announcement, made in English and pointedly repeated in Spanish, seemed to signal his appreciation of the role he could play by taking on a president who rode a wave of xenophobia into office.

Most media outlets didn’t mention the subtle power of the moment that began when Castro said, “Cuando mi abuela llego aqui,” and repeated the story he had just told in English about how his grandmother could never have imagined that, two generations after her arrival from Mexico, one grandson would be a member of Congress and the other would be running for the White House. Instead, reporters noted his lack of fluency in Spanish, a choice he later described to Maddow as the beginning of a double standard of campaign coverage that plagues candidates of color.

Of course, Castro must reflect on his own failure to garner significant support even among Hispanics. A member of his inner circle told me in November that his strategy was focused on shaking up the race with strong showings in South Carolina—the state with the fifth-fastest growing Hispanic population in the last decade—and Hispanic-friendly Nevada. Judging from massive email appeals toward the end of last year, he ran out of money to pull it off.

Meanwhile, his departure from the race may exacerbate a growing feeling among Hispanics that they are being ignored by the top-tier candidates, a disaffection the Washington Post reported on last month. The departure of the only Hispanic contender in the presidential race before a single vote has been cast could squander an opportunity to expand the party’s base of Hispanics in the face of Trump’s stridently anti-immigration rhetoric.

Democrats must reckon with how the most diverse field of candidates in the history of any political party has been winnowed to a handful of top-tier white contenders before a single vote or caucus has taken place. Just two major candidates of color remain: Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey and businessman Andrew Yang. As my former colleague R.G. Ratcliffe has long complained, the primary system now relies almost exclusively on money and national name identification. It’s a system that favors white candidates at a time of massive demographic transformation in our country. Two states with a relative lack of ethnic diversity—Iowa and New Hampshire—vote first and thus have an outsized influence on the nomination process.

After failing to make the cut for the televised debate in November, Castro himself bravely (or foolishly?) called out this problem with Iowa’s first-in-the-nation status while campaigning in Iowa. It was yet another instance in which he reframed the debate for his party and became a voice for the underserved. He proposed plans to help Native Americans, for protecting animals, and for lead abatement in water pipes. His call to decriminalize unauthorized border crossings became a position that other candidates soon adopted. His proposal for police reform sent a consistent message about reforming one of the deadliest manifestations of white privilege.

Ultimately, it was his ethnicity that may have had the greatest impact on this year’s election. His influence on immigration policy, for example, would have been a harder sell for his white rivals had he not been in the race. The last time I spoke with Castro at length was when he visited Matamoros to see the conditions in which thousands of Central Americans were living as a result of Trump’s Remain in Mexico policy. He easily worked his way through the crowd, with many speaking to him in Spanish. How much he understood may be debatable, but he seemed approachable. By contrast, a few months later, Jill Biden served as a proxy for her husband, Joe Biden, making the same journey to Matamoros, but seeming out of place, perhaps even uncomfortable in this harsh environment.

At 45, Castro’s age provided a stark contrast with Trump, who is 73; Castro’s penchant for deliberation contrasts with Trump’s impulsivity. But it’s his heritage that could have made Castro the perfect foil to Trump in November. Trump’s winning campaign rhetoric four years ago was steeped in attacks on Hispanics and Latin American countries. Shunting aside so early a voice that could more directly confront such rhetoric is a dangerous gamble for the Democrats. While the remaining Democratic candidates are certain to speak out against xenophobia, one criticism of last month’s debate in heavily Hispanic California (a debate for which Castro failed to qualify) is that the candidates ignored issues of concern to Hispanics.

I have had several conversations with Castro about his place in history. He understands the ways in which his heritage adds additional dimensions to his political calculus. As he told Maddow, “I said things that other candidates weren’t willing to say.” Along the way, Castro showed his critics that he has huevos.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Julian Castro