On a streaky blue morning in early 1976 Shearn Rovinsky curled up in the backseat of his car to die. Rovinsky had been a member of Zale Corporation’s ruling family for seventeen years, a mathematical whiz recognized for his brilliance as the company’s chief financial officer and number one money manager. He was fond of saying that he loved Zale as much as he loved his own life and family. But on this particular work day Shearn Rovinsky did not make the usual drive from his suburban Dallas home to the headquarters of the world’s largest retail jeweler at Diamond Park. Instead, he waited until his wife had taken the children off to school, then closed his garage door, started his car, and climbed into the backseat, apparently hoping to succumb to the sweet sleep of carbon monoxide poisoning. In a suicide note left for Zale chairman Ben Lipshy, Rovinsky promised to “take the company’s secrets . . . to the grave.”

Ben Lipshy had already been in his office for nearly three hours when Shearn Rovinsky decided to kill himself. Famous for arriving at the building at 5:30 every morning, Lipshy had spent much of that time in consultation with his nephew, company president Donald Zale, the 43-year-old son of Zale’s founder, Morris B. (“M.B.”) Zale. The day before, Donny and Ben had confronted Rovinsky about some $600,000 found missing from the corporation’s accounts after a weeklong investigation prompted by a Rovinsky assistant. After several controversial meetings and much circumlocution, Rovinsky had finally been given 24 hours to come up with a satisfactory explanation for the missing money.

Now Rovinsky’s time had just about run out, and he had not shown up at the Zale’s Building. With M.B. out of town, Donny and Ben had to decide what to do. Ben kept dialing Rovinsky’s home phone number and kept getting a busy signal. Then the maid answered and said no one was home.

Meanwhile, Ben Lipshy’s son Bruce, the company’s 35-year-old senior vice president, was engaging in some decision making of his own. The day before, Bruce had discovered that 26- year-old Shari Oliver, a svelte part-Indian “executive secretary” with whom he had been having an affair, had also been having an affair with the hapless Rovinsky. About 8:30 on the fateful morning of February 6, Bruce summoned Shari to his eighteenth-floor office.

According to her recollection of the meeting (Lipshy will not discuss it), the younger Lipshy lit into her the moment she came into the room.

“I know, baby, I know!” he shouted. His eyes were boiling—not with tears but with liquid rage.

“I don’t understand,” Shari answered.

“I know who your boyfriend is!” Bruce shouted. “And this morning we fired him.”

Then, according to Ms. Oliver, Bruce began to scream. “Just get out!” he yelled. “Tell your boss you have to be home with your baby. Anything. Just get out!”

Bursting into tears, Shari turned and ran out of the office. She frantically telephoned her embattled “boyfriend” to see if what Bruce had told her was really true.

But this time Rovinsky himself answered the phone. His suicide attempt had failed as miserably as his accounting acrobatics. Clumsily, luckily—some would later say, calculatingly—he had rolled up the windows on his car, creating an air bubble that kept him alive until his maid discovered him. Neither Rovinsky, nor the company’s secrets, would make it so easily to the grave.

Meanwhile, back in the glittering Zale headquarters building, the tension mounted. There were guards everywhere, especially around the bookkeeping vault on the fourth floor, where no one was allowed in or out. Every employee in the building knew something was wrong, but no one was sure what it was. The initial rumor was that the company’s chief financial officer had been caught with his hand in the till and had fled to Brazil. Then, around midmorning, a more somber rumor arrived: Rovinsky had not flown off to Brazil; he had apparently committed suicide instead.

Up on the eighteenth floor, Donny, Ben, and Bruce and their legal and public-relations counsel prepared an urgent press release announcing that Sol Shearn Rovinsky had been fired for “violation of company policy.” By the time that news came out, Shari Oliver and Rovinsky were on their way to her mother’s home in Oklahoma, where they could get away from the crisis and where she could help prevent another suicide attempt.

As the day wore on, several other family members swung into action. While Shearn’s wife, Linda Burk Rovinsky, grappled with a severe bout of anxiety, Ben Lipshy’s daughter, Joy Burk, picked up the three youngest Rovinsky children at school and took them back to the Rovinsky house on Yamini. By the time the Rovinsky’s eldest son Kirk, 16, arrived home, he found the house under the command of his uncle, Larry Burk, Joy’s husband. According to Kirk’s recollection, Burk informed him that his father had been caught stealing and that his whereabouts were unknown, but that he had probably killed himself. Then Burk told the boy that he, Burk, would be head of the household thenceforth, adding solemnly, “Your father’s not part of the family anymore.”

That, in the eyes of Shearn Rovinsky, was the unkindest cut in the whole affair; the blow which would ultimately compel him to attack his own family—one of the state’s most powerful—in the harsh glare of the public limelight. But it was the family that would move first.

The next day, Bruce Lipshy personally filed charges of criminal theft against the still-missing Rovinsky with the Dallas County district attorney. Returning to Diamond Park to clean out Rovinsky’s desk that afternoon, Bruce confided to a friend that “this is going to hurt us”—meaning, of course, the family members still in good standing—“as much as anyone.”

That turned out to be one of the grossest understatements in the 53-year history of the company. For when he was finally brought to trial last fall, Rovinsky was acquitted of the theft charges. Worse, his attorneys, George Milner and Billy Ravkind, cleverly turned the tables and put the Zale Corporation on trial. They alleged that Rovinsky had taken the $600,000 as “secret compensation” for carrying out a whole series of multimillion-dollar tax evasion and secret payment schemes that permeated the company’s recent history. In the course of the trial, many of these charges were substantiated in whole or in part by documentary evidence and by the admissions of top Zale Corporation officers and employees.

Suddenly, the house of Zale was rocked to its foundations. The company’s stock plunged from $25 a share to less than $12. The IRS and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), already aroused by Rovinsky’s pretrial allegations, spurred on separate criminal and civil investigations, while three groups of outside shareholders pressed lawsuits aimed at removing the company’s top management. The corporate family structure Fortune magazine once described as “nepotism that works” was threatened with virtual annihilation.

That threat is still pending. But the Rovinsky affair has not simply been diminished by its revelations of corporate misdeeds and amorality—those, by now, are fairly common stuff. Rather, the most interesting aspect of the story is the glimpse it has given of this exceedingly powerful Jewish family and the unique institution they have created.

Zale Corporation is not, as many still believe, just a chain of cheap jewelry stores. It is the world leader of its industry, a $650-million-a-year multinational conglomerate that owns a full line of jewelry houses from the discount level to the “carriage trade” level of its Corrigan’s stores in Houston, its Lambert Brothers stores in New York, and its Bailey, Banks & Biddle stores in Philadelphia. Zale also owns 100 drugstores under the Skillern’s name, the Karotkin furniture chain, newsstands at Dallas-Fort Worth airport, the Butler Shoe Company, the Cullum and Boren sporting goods chain, and the Sugerman military insignia and optical/electronics company of San Antonio; until recently, it also owned the Levine’s department store chain. Zale has family, business, and political ties that run deep into the heart of the Texas establishment, linking it to such institutions as Republic of Texas, the state’s second-largest bank holding company; Commercial Metals, one of the state’s twenty largest corporations; and both major political parties. And despite being a “public” corporation it remains 50 per cent owned by the family and family friends who operate it, a corporate anachronism that has made millionaires of them all.

To understand the tragedy that has befallen the house of M. B. Zale, you must understand what it means to be a member of this family. Especially a member who, as the Yiddish phrase goes, knows the emis—the “real truth.” The real truth about the Jewish merchant heritage and the small-town prescription drugstore beginnings. The real truth about the decision to go public and the drive for bigness. The real truth about the sort of pace and practices required to keep Zale Corporation the world’s largest and most profitable, retail jeweler.

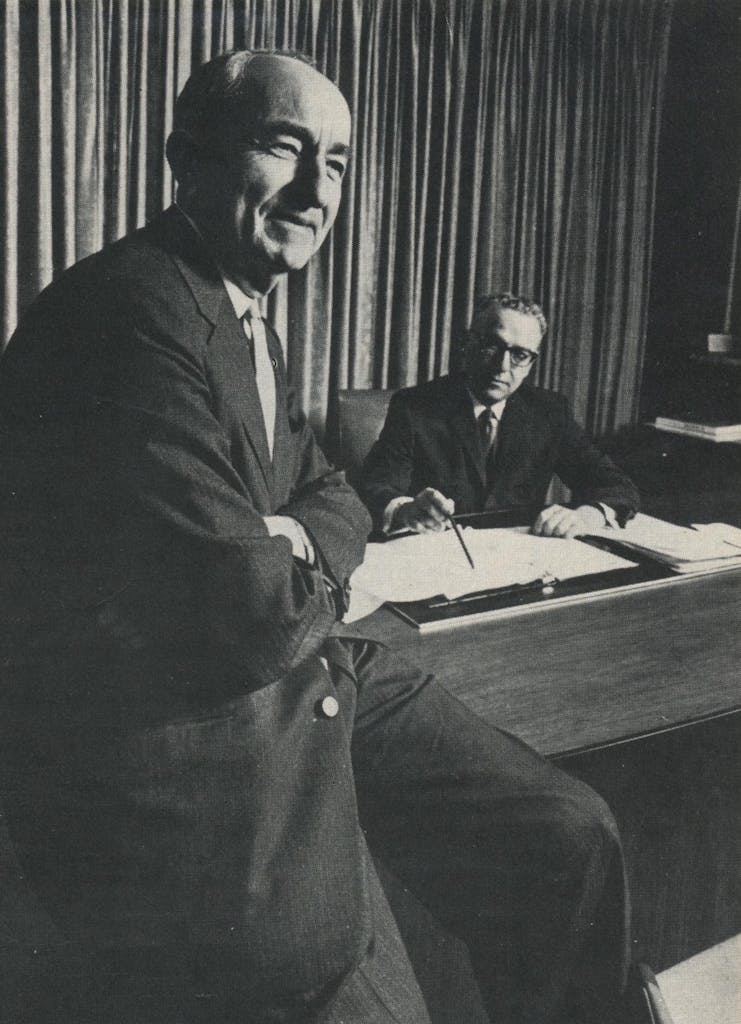

As in so many great family stories, the emis begins and ends with the father, the family patriarch, Morris Bernard Zale, “Mister M.B.” Physically, M. B. Zale is not a very imposing man: he is short and skinny, with dark bushy eyebrows, steady gray-green eyes, and enormous ears set on a balding, angular head, hardly the sort of figure one would expect to play godfather to a great dominion. But the range of his mind and the intensity of his energy are astounding. At the age of 76, he has been in “official” retirement for half a decade; his brother-in-law, Ben Lipshy, his son Donny, and, increasingly, his nephew Bruce Lipshy, have taken over the corporate family leadership—at least in title.

But there is no question that M.B. still passes on every major corporate and family decision. He still logs tens of thousands of miles in world travel each year; he still knows his business from top to bottom. Nearly every employee in his company, nearly every member of his family will stand hand on foot to please him, for despite his advancing years, Morris Zale is still der mensh—“the heavy.”

Some time around 1905, Morris’ father, Sam Zalessky, managed to immigrate to America, thanks to some money sent to him in the Russian-Polish border town of Shereshov by his wife’s brother, Sam Kruger. Kruger had begun a budding jewelry business in Fort Worth and Sam Zalessky went to work for him in the family store. The jewelry business was a natural one for Jewish immigrant clans like the Krugers and Zalesskys. Excluded from many European countries and barred from owning property in others, Jews had traditionally gravitated toward portable professions and toward merchandise with high per-weight value. Diamonds and jewelry were more dependable and more widely negotiable than the fluctuating currencies of Europe. They were of incontrovertible worth and were easy to carry from place to place, small enough, in fact, to be smuggled out of a country in one’s teeth. So just as they had become the continent’s moneylenders, hoarders of gold and silver, Europe’s Jews had also come to dominate the trade in precious gems. When they immigrated to America, they brought their acumen and expertise, even though they often had to leave their merchandise behind. Three years after coming to America, Zalessky had saved enough to send for Morris and his mother.

Morris was not yet eight years old when he first crossed the Atlantic on a ship crowded with huddling women in tattered old scarves and shawls and bearded men in high hats and dusty black coats. Had he been capable of grasping the history of the time, he would have known himself to be a part of the third and largest wave of Jewish immigrants to America, one of the lowly Eastern European Jews that even the Sephardic of the first wave and the German doktors and meisters of the second wave disdained and called “kikes.”

If the Zalesskys had chosen to stay in the ghettos of old New York, Morris might well have been exposed to these internecine class distinctions at an early age and found his horizons limited accordingly. But after passing the dreaded medical tests on Ellis Island, Morris and his mother moved quickly through the pushcart-crowded streets and boarded a train for Texas.

Here, the Zalesskys would encounter their share of prejudice, but conditions were generally more benign than in the East and the class structure more flexible. There was also a considerable and fairly well-accepted Jewish presence in the state, particularly in the booming city of Dallas. In fact, by the late 1890s great families like the Titches, the Sangers, the Harrises, and the Goettingers had already forged lasting business ties with the gentile establishment and were conducting their own high-society affairs with as much lavishness as any goyish debutante ball in town. Among Jews themselves, the basic distinction was between city and country, between those who were still close to the rural rag-seller tradition and those who felt that their income and urbanity put them above and beyond the indignities of the past. If Dallas was the center of the new Jewish affluence, Fort Worth, where Morris’ Uncle Sam Kruger had his store, was the “jumping-off place” for those who had yet to make their way. As Morris would recall years later when he recounted his life to University of Texas oral historians Floyd Brandt and Joe Frantz, “There was no place else to go.”

For half a dozen years, young Morris went to school in Fort Worth and spent afternoons and weekends at his uncle’s store. Then, at thirteen, he quit school and went to work full time. He soon became a traveling salesman, peddling his uncle’s wares down the dirt roads and in the small towns of North Texas, places like Ranger, Brackenridge, and Burkburnett, villages light-years removed from Shereshov.

In 1922, the oil boom hit Graham, and Morris, by then a veteran salesman of 21, moved to town and opened a small drugstore that sold everything from potions and poultices to jewelry and Victrolas. These early days in Graham were the days of Prohibition, and the ambitious young merchant also engaged in the lucrative “prescription” liquor trade. Indeed, while men like Joseph Kennedy made their family fortunes bootlegging on the East Coast, Morris chipped away selling booze by the pint bottle; conveniently, there was a “prescribing” doctor in the office above the store.

The Ku Klux Klan, however, had come back strong in the twenties, and the new objects of its bigotry were not just blacks, but Catholics, Jews, and immigrants. As elsewhere, the Graham KKK had so cloaked its hatred in the robes of respectability that even the town’s most prominent citizens were proud members. Law-abiding folk by day, by night they would burn crosses on the hill east of town. The message to an immigrant with a funny name and one of only two Jews in town was clear. But by this time, Morris had accumulated several debts and was forced to auction off all his merchandise before he could leave town. Fortunately, Uncle Sam Kruger was vacating an old storefront in Wichita Falls. Though he still made a small profit on his Graham venture, the experience would rankle him for many years to come.

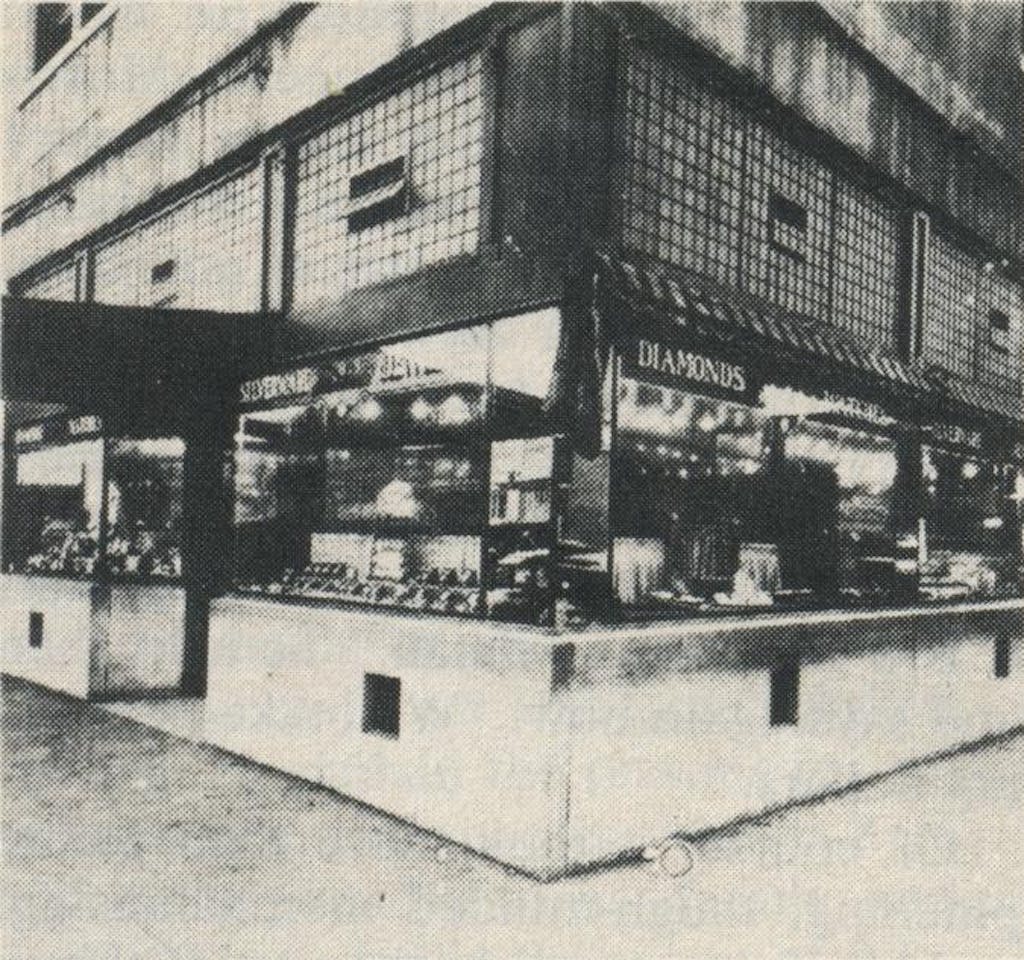

Better days were soon at hand. On March 29, 1924, Morris took the small profit he had made in Graham and with his brother, William Zale, and Uncle Sam Kruger incorporated the first “Zale” jewelry store at the corner of Eighth Street and Ohio Avenue in Wichita Falls. It was the tiny flagship of what was destined to become a huge corporation.

Setting the style and substantive principles that would guide him into the future, Morris vigorously attacked his new business, spending virtually every waking minute in or around the store. For him, there was no separation of work and play. He lived and loved every aspect of his trade and insisted on knowing everything about every transaction.

At the same time, he never succumbed to the “love of merchandise” for which he often castigated his uncle. Morris recognized that an interest in jewelry stores and an interest in what he sharply termed “museums” were not compatible: no matter how pretty it was, the merchandise had to be moved. Thrifty to the point of being penurious, Morris kept a tight rein on each expense. “This is not a business of genius, it is a business of detail,” he said then and says again now. “We make pennies, not dollars.”

Of course, it took more than penny pinching, tough-minded merchandising, and blind energy to do the sort of things Morris Zale was beginning to do, and it was during these early days in Wichita Falls that he got the inspiration upon which the greatest share of his future success would rest—the idea of selling jewelry to modest-income customers.

At the time, most jewelry stores were like the ones owned by Morris’ uncle. They were austere, formal places that invited only the so-called “quality people.” To the common man, these stores were as forbidding in atmosphere and clientele as they were in price. But Morris Zale changed all that, starting with his uncle’s old Wichita Falls location. He introduced into his jewelry store something of the atmosphere of his old drugstore back in Graham. Keeping the checkered tile floor swept but uncarpeted, he filled the cabinets and shelves not only with bracelets and gems but also with pots and pans, gifts, and specialty goods. Thanks to these “traffic items” and to services like watch and eyeglasses repair, the store became a place that could attract people for more than a once-in-a-lifetime purchase like a wedding ring.

Morris also did his best to make his customers feel wanted and needed regardless of their means. More, he helped enhance their means by selling his merchandise on liberally arranged terms of credit. Morris Zale was not the world’s first credit jeweler—in fact, he claims to have learned the technique from the Chicago diamond suppliers—but, more than anyone else, he introduced and popularized the idea at a retail level. He and his brother would go out of their way to keep a customer, shaving the price, extending the due date, doing whatever they could to build up a broad-based and faithful clientele.

It was also during this period that Morris Zale began building an even greater commercial asset—his family.

In 1924, he married Edna Lipshy, the dutiful daughter of another East European Jewish immigrant couple who were struggling to make a living selling vegetables from a pushcart in Wichita Falls.

From the outset, their union produced growth for the company and prosperity for the two families. Quick to recognize the genius of their brother-in-law, four of Edna’s seven brothers and sisters soon went to work for Morris or married people who did; the only male sibling in the Lipshy family who did not enter the Zale business wound up in an insane asylum. Together, they expanded the sales force, while keeping the enterprise family controlled, something that would continue to pay inestimable dividends as the company and the family grew larger and larger. Asked years later to explain the reasons for his enormous financial success, Morris Zale would point proudly to his family and remark, “That’s really the secret of it.”

The Lipshy destined to go the farthest within the company ranks was Edna’s younger brother, Ben, the current chairman. Ben began as a clerk and all-around errand boy in the Wichita Falls store in 1926 at sixteen. His starting salary was $16 a month; characteristically, Morris withheld part of the money so that the boy would not squander it all at once. Such precaution proved unnecessary. Ben soon showed himself to be no less thrifty and diligent than his brother-in-law. In fact, he made a point of working even longer and harder than Morris did, often arriving at the store at 4 and 5 o’clock in the morning. “Here was a fellow whose concentration on the job was extraordinary; and whose ability to get the work done with a minimum of discussion was and still is a rare talent,” M.B. would remark years later with admiration.

Still, the two were as different as diamonds and gold. Though both displayed a special brilliance, Morris was talkative and personable and blessed with a great breadth of vision, while Ben was quiet and diffident, absorbed in detail. Morris was quick and decisive; Ben was slow and cautionary. They were, in short, wonderful complements to each other. Nonetheless, the true genius of the two was Morris, and Ben was fated to live out his life in M.B.’s shadow.

Ben and Bill Zale, Morris’ younger brother, strengthened and broadened the Zale-Lipshy family ties by marrying a pair of loquacious Wichita Falls sisters, Udys and Sylvia Weinstein. Like other great family dynasties, the Zale-Lipshy clan grew tighter and more fiercely loyal as its founders struggled through life together. They cultivated few friends outside their kinship group, in part because of their time-consuming devotion to the family business and in part because a certain introversion was one of the widely shared family traits. Proudly iconoclastic, they set their own standards and style in everything they did. Education is one particularly ironic example. Though the family now contributes generously to support higher education, the first generation of the clan takes pride in the fact that none of them ever finished high school. The second generation, in turn, is proud that only three of their number ever finished college, a fact they delight in underscoring with the prideful reminder, “We don’t always do everything by the book.”

Morris’ attention to this budding family and to his early clientele proved its worth with the onslaught of the Great Depression. After half a decade of steady growth and the addition of two more stores, the family business ran into a half decade of stagnation and a severe credit squeeze. But rather than call in the accounts and risk losing the clientele they had cultivated, the family joined together to economize at every level. Morris cut down on overhead, reduced his sales force, cut back salaries, and allowed his customers more time to settle their accounts. As a result, the house of Zale weathered the hard times and kept the foundation for second and third generations of jewelry customers and jewelry sellers. (Ironically, while Morris Zale recommended credit to his customers, he remained firm in his determination to avoid bank borrowing to finance his business. In fact, after leaving Graham in 1924, he borrowed only once—and that time only $10,000—until 1956, shortly before Zale’s went public.)

When the Depression began to bottom out, Morris resumed expanding the family chain across North Texas and into southern Oklahoma. As a rule, he looked for what he then considered “medium-sized” cities and towns, places where the business was brisk but the competition was not too expensive. Bill Zale took on the management of Tulsa, and Ben Lipshy started store number four in Amarillo. The company opened store number six in Springfield, Missouri, then the farthest out-of-state venture; in 1937, Zale’s opened its first Dallas store, which was number seven. World War II brought the chain more business than ever, much of it credit sales to departing servicemen, their brides and families. Zale’s gained four more stores, completing the group company insiders refer to as “the first eleven.”

In 1944, Zale’s came to another crossroads. Until then, Zale’s had been exclusively a discount jeweler. But the approaching end of the war promised to bring home flocks of marriageable servicemen and a new affluence. There were signs of an emerging petrochemical industry and a population boom in Texas and the Southwest. Morris Zale decided it was time to fill out the company’s portfolio, so to speak, by moving into the high-priced jewelry lines. Conveniently, Leo Corrigan’s fine jewelry store in Houston was for sale, and Zale’s snatched it up.

By 1947, Morris and the family company were doing an annual business of about $10 million a year in three states. They had clearly outgrown Wichita Falls and were badly in need of a headquarters site serviced by a transportation network with arteries linking the chain’s major outlets. The logical choice was Dallas. Morris found a home for the company in a two-story building on North Akard Street and led the family flock into comfortable and unostentatious North Dallas neighborhoods. He soon made fast friends with Fred Florence, the Jewish wunderkind of Republic National Bank, and formed a lasting business relationship; in 1963 he joined the Republic board of directors.

Over the next ten years, Zale’s grew nearly fourfold. By the late fifties, company sales had increased to $60 million per year; though this was just a fraction of the total industry sales and the Zale Corporation annual sales of the future, the company was already the world’s largest retail jewelry chain. Morris always said that he had no “big plan,” that each expansionary move was but a “step next door.” But to continue his own metaphor, it did not take Morris long to acquire the whole block and then the whole neighborhood. In the years to come, he quickly took Zale’s across the country and around the world, from the towns of North Texas to London, Switzerland, Belgium, Brazil, South Africa, Israel, India, Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Puerto Rico. Perhaps his greatest strength was his ability to adapt to change and reap profits from it. He was, for example, one of the first retailers in the country to computerize his operations, beginning in 1954 with an IBM 350 he saw at an exhibition in San Francisco. When commercial jet service was perfected, he quickly seized the opportunity to go global on a major scale. Later years saw the introduction of regular polygraph tests for employees and the installation of point-of-sale TV-screen computers to allow daily monitoring of business.

Of course, at no time did Morris think solely of business. Along with Ben Lipshy, who with his socially fervent wife, Udys, often acted as Zale’s official public figurehead, Morris also devoted considerable time and money to civic and philanthropic activities. Though hardly a giver of Rockefeller proportions, he became a big contributor to and board member of Bishop College, a black college south of Dallas, and he gave generously to area hospitals. In 1951 he established the Zale Foundation, which has a current endowment of $5.5 million. The foundation has supported projects ranging from educational programs to train black ministers, doctors, and lawyers (Morris Zale’s scholarship support was, for example, one of the chief behind-the-scenes factors in the integration of the SMU student body in 1955) to programs that brought milk to starving children in India.

Morris Zale’s liberalism has been shaped by continuing personal experience. “Being excluded from a lot of places sort of wakes you up,” he told the two oral historians. “I’ll tell you frankly that there are very few times that I had any feeling of being wanted in the gentile community. I mean by that socially.” (This liberalism has conveniently found no contradiction in Zale’s close working relationship with the South African diamond suppliers.)

Politically, Morris Zale has supported one candidate or another as much for business as for ideological reasons, something about which more will be said later. Two of the men he has most admired are Lyndon Johnson and John Connally, the first having hosted him at the LBJ Ranch and the second having spoken to the company’s annual meeting. He has also “tolerated” company employees who engage in all sorts of fringe organizations, including some who were in the peace movements of World War II and the Viet Nam War. Though the top echelons of the company always were and still remain occupied by Jewish males, the company reports that about 15 to 20 per cent of its current employees and 33 per cent of new hirings are blacks and other minorities. Women, however, have not fared quite so well, a fact some attribute to attitudes of the Jewish males who run the company. Traditionally, females have composed the vast majority of the direct sales force in the Zale’s stores, but they are seldom found in top managerial or executive positions.

The very top positions are reserved for the family, but Morris always took pride in evaluating his relatives’ abilities with cold objectivity, regardless of the repercussions. One good example came at still another company crossroads, the great reorganization of 1957, when Morris decided to take the company public and move up from president to the newly created post of chairman of the board. Instead of passing the presidency to brother and co-founder Bill, he gave the job to Ben Lipshy and kicked his brother upstairs. Despite all the single and double family ties, the decision created something of a family schism. According to company insiders, Bill Zale’s opinions continued to be heard and often acted upon by the highest family councils, but he was no longer among the family power brokers. His sons, meanwhile, worked only briefly for the company, then left to pursue other careers and enjoy their considerable inheritances.

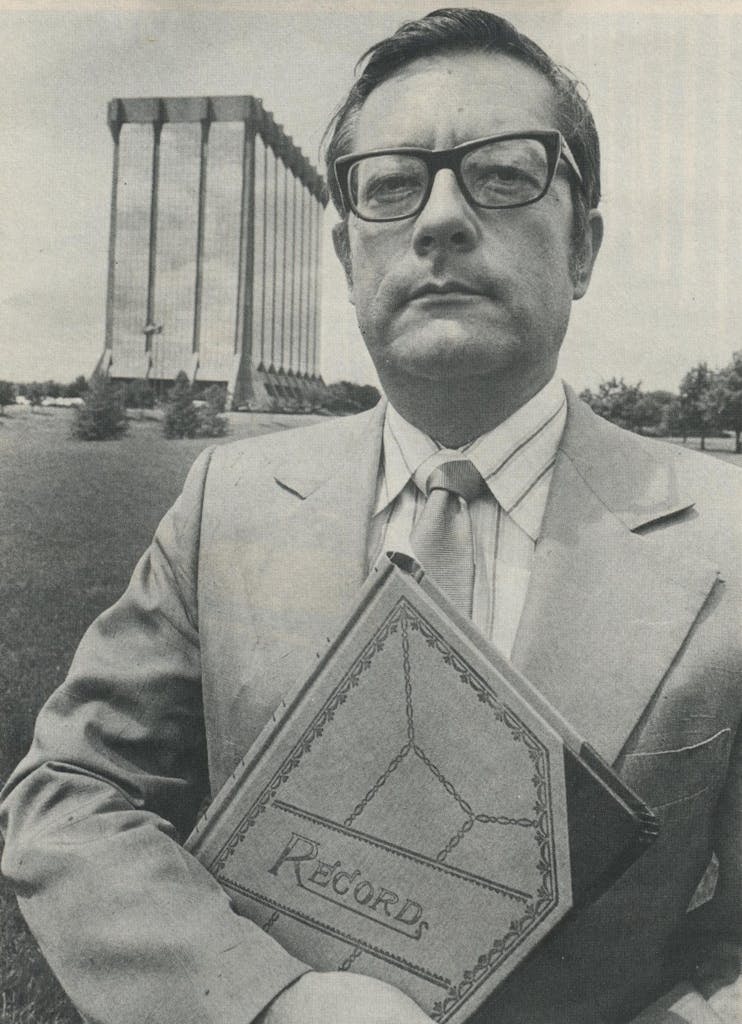

About the time of this schism two portentous young men joined the company ranks. One was Morris Zale’s second son, Donny. An SMU graduate who did a brief stint at Texas A&M, Donny never displayed his old man’s absorptive intelligence. But unlike some of his cousins and siblings, Donny always showed tremendous drive and seemed to have a crystal-clear vision of his corporate destiny. He began working in Wichita Falls store number one at the age of six and continued to work for his father on Saturdays and on afternoons after school when the family moved to Dallas. Short and stocky with a wide, rounded face, he had already developed a sharp and abrasive self-confidence and outward toughness by the time he joined the company full time in 1954. Though he twice failed the certified public accountant’s examination, one of Donny’s first major jobs was supervising the accounting department. His task: to set up the bookkeeping principles that would guide the company through the coming boom of the sixties. It was an assignment that would one day come back to haunt him.

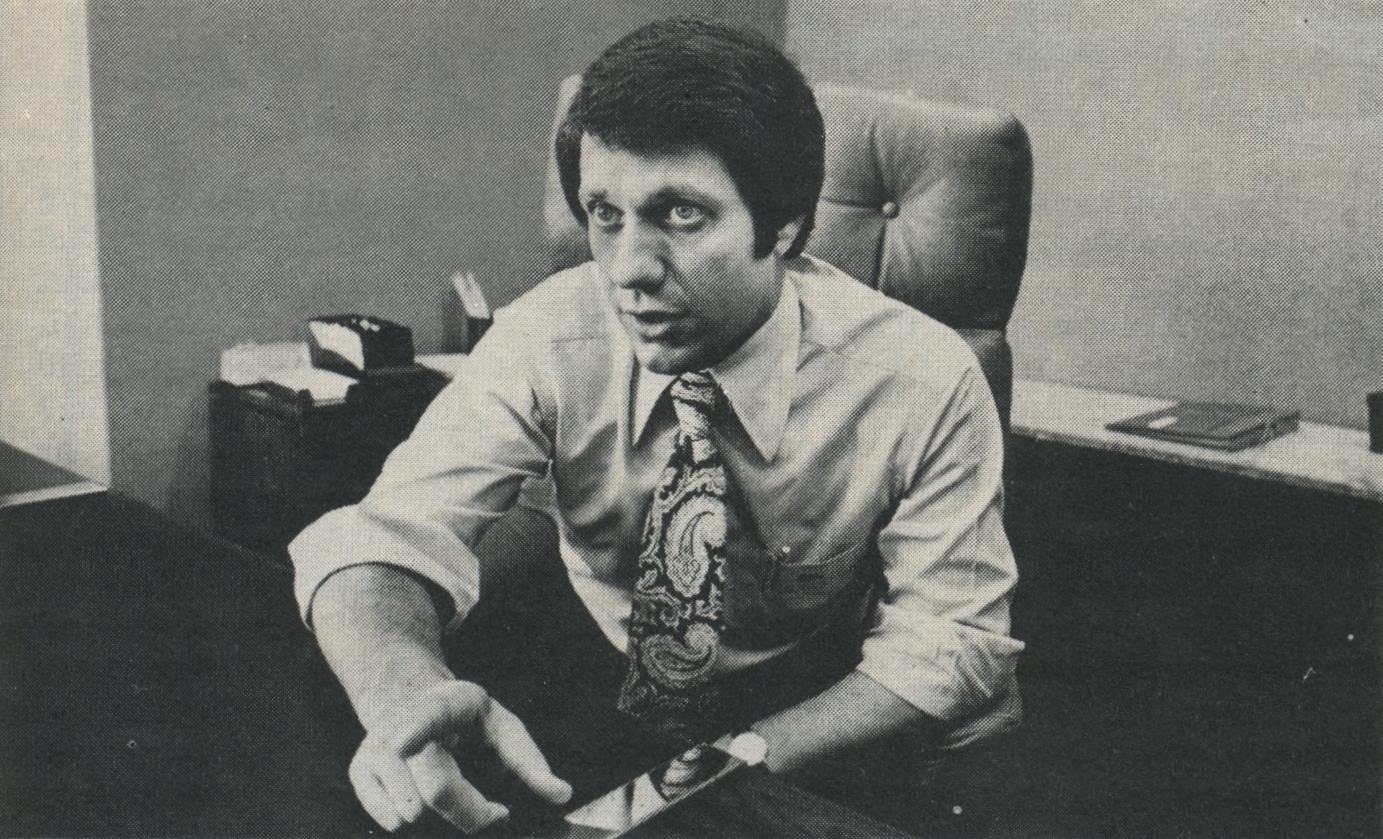

The other ominous young figure to enter the corporate-family picture during the fifties was Sol Shearn Rovinsky. Also short and bespectacled, but with a lean, delicate build and crafty, arched eyebrows, Rovinsky was the opposite of Donny Zale in almost every way. The son of an executive with Southwestern Life Insurance Company, he had been a publicly acclaimed whiz kid. He had a photographic memory that had enabled him at the age of six to memorize the Gettysburg Address from a first reading. But his true gift was for numbers. Given a person’s birth date, he could tell him on what day of the week he was born—instantly. These and other numerical talents won him recognition in Ripley’s Believe It or Not before he was ten years old, but because of constant requests to perform, they also gave his personality something of a beating. By the age of seven, young Shearn was under doctors’ orders not to display his talents without parental permission.

Rovinsky attended Highland Park High School in Dallas, where he was a classmate and casual acquaintance of Donald Zale. After graduating from the University of Texas, he did a brief stint as an officer aboard the aircraft carrier Yorktown, then joined the IRS as a special agent and went to school to get his CPA certificate. In 1958, Rovinsky married Linda Burk, the daughter of a successful Dallas blue-jeans manufacturer. Linda’s brother Larry had recently married Joy Lipshy, Ben’s daughter, and in short order, Linda made the appropriate connections for her new husband. In the fall of 1959, Shearn joined his former schoolmate Donny Zale in the company’s accounting department. As time went on the Rovinsky’s and the Lipshy family’s offspring would have children the same ages, send them to the same private schools, and celebrate the traditional Jewish Seder in each other’s homes.

Not too surprisingly, this cozy family relationship has been utterly destroyed by the recent allegations and counter-allegations. But remarkably enough, both Rovinsky and present and former Zale loyalists paint similar portraits of the company and its ruling family as they fought their way to power and prestige in the sixties and seventies.

Zale’s struggle to modernize and grow—the period insiders refer to as the company’s “phase two” of growth—actually begins with two critical executive decisions of the late fifties. The first was the move in 1957 to become a publicly held company. Oddly enough, the decision was not primarily motivated by the need to raise money from equity markets; in fact, the company was so underleveraged that it could easily have raised as much money from banks and other sources as it did from its stock offerings. Rather, the main reason for going public had to do with the family and with taxes. Morris Zale and the other senior members of the clan were advancing in years and could easily envision their fortunes—which already amounted to several million dollars apiece—being decimated by estate taxes. By converting their personal assets to corporation stock and keeping the majority of stock for themselves, the Zales and Lipshys could protect themselves and their descendants and still retain control over their company. Or so they thought. In reality, the decision to go public also brought with it a tremendous amount of exposure, since the corporate family opened itself and the company for the first time to the scrutiny of a host of regulatory agencies. The true implications of this decision wouldn’t become apparent until almost two decades later when Zale and Shearn Rovinsky began their fight to the finish.

The second critical decision the Zale company leaders made in the late fifties was to begin cutting and polishing their own diamonds on a large scale. This decision meant they would have to broaden an already existing relationship on the international diamond Syndicate by gaining an invitation to participate in the Syndicate’s diamond sales in London. By becoming the only retailer invited to the Syndicate sales, Zale gained an unprecedented privilege and potential. Zale could now acquire the raw materials of its product—the rough or uncut diamonds—directly from the people who mined them, thus eliminating entirely one middleman other retailers could not avoid. Much like today’s major oil companies, Zale could add a measure of “vertical integration” to its operations by becoming involved in nearly all phases of its industry—from cutting and polishing the stones and manufacturing the jewelry to marketing and retailing.

Being invited to participate in the Syndicate sales also meant joining an elite and arcane fraternity unlike any other business organization in the world, with the possible exception of the OPEC cartel. The Syndicate consists solely of the seller, sometimes called the Central Selling Organization or CSO. This, in turn, is another name for the DeBeers Consolidated Mines of London and South Africa, which controls about 80 per cent of the world’s rough diamonds. Sales are made exclusively on DeBeers’ London exchange to some 250 approved buyers about ten times per year. In 1975, the total was 2.5 million carats for a gross of $7.5 billion. The other major world diamond suppliers are the Russians and the Angolans, but neither provides much competition for the South African cartel.

Transactions on the London exchange are based on blind trust. All sales are made in sealed parcels called “sites.” The buyer does not even see what he is getting until after his purchase is completed. Aside from applying for a certain type of assortment, he has almost no control over the shape or quality of the diamonds he gets. In most cases the seller simply quotes the weight and price; the buyer can take it or leave it. On large stones, however, DeBeers does leave some room for price negotiations.

The shipment and transaction of these diamonds is a matter of mystery and top security. Zale executives often say they do not know how diamonds are shipped and would not tell if they did. However, a company spokesman says that the bulk of the diamonds Zale receives are sent by registered mail, often to a low-profile addressee. For example, when Zale brought the massive 130-carat $1.3 million Light of Peace diamond into the country, it was mailed to M. B. Zale’s granddaughter in New York.

Obviously, business of this sort could not be conducted for very long without high ethical standards. The buyer must feel confident he is not being systematically defrauded; the seller must fill his sites with a view toward the needs and capacities of the buyer. Both must maintain impeccable credit and credibility. The Yiddish phrase for these transactions—as well as for deals of trust on all levels of the diamond business—is the salutation “mazel und brucha,” which literally translates “luck and blessing.” More than a Semitic rendition of let the buyer beware, mazel und brucha is the industry expression for honor and integrity.

Closely connected with the Syndicate are world diamond trading markets in Antwerp, Belgium and Tel Aviv, Israel, where stones are bought and sold after being acquired on the London exchange. Both Israel and Belgium grant jewelers special tax advantages and minimal reporting requirements that some say amount to officially sanctioned black markets.

Blessed with its special rights of participation in these two special societies, Zale surged into the sixties with a force none of its competitors could hope to match. By the end of the decade, the corporation had expanded from 140 to over 1000 stores and increased its sales volume twelvefold. By 1975, the year before all the trouble hit, Zale had 1700 stores with sales of $607 million per year, and profits of $30 million. Gordon’s Jewelers, its closest rival, had only 386 stores with annual sales of $197 million.

Thanks in part to some uncharacteristic skittishness on the part of its founder, the company also became a conglomerate. Worried that the development of the synthetic diamond would rip the bottom out of his jewelry business, M.B. decided in 1963 that the company should begin to diversify. The company’s first acquisition was the Skillern’s drugstore chain, a symbolic return to Morris Zale’s commercial roots in Graham. Soon after, Zale acquired the Butler Shoe Company of Atlanta, the Cullum and Boren sporting goods chain, and the family-connected Levine’s junior department store chain. Morris Zale began to think of his enterprise not as a jewelry business but as a pure retailing business, a company concerned with the movement of merchandise, regardless of whether that merchandise be 24-carat pendants, size 14 wash-and-wear dresses, high-heel shoes, double-stitched baseballs, or bottles of mouthwash. Most of these acquisitions proved successful with the exception of Levine’s, which Zale managed to sell early this year after ten years of losses totaling nearly $7 million.

In the process, the mechanics of Zale’s daily business became infinitely more complex. Zale had to be tuned to the fluctuating world price of gold, the politics of underdeveloped mineral-producing countries, women’s fashions, the price of cotton and synthetics, military recruitment projections, trends in sports and leisure, and government food and drug regulations, to name but a few of its diverse considerations. Even the marketing of an ostensibly simple jewelry item like a five-stone diamond cluster ring became a major project. To make only five such rings for each jewelry store would require finding 25,000 diamonds of the same size and weight and color, a task roughly akin to finding 25,000 dollar bills with the same pattern of folds and wrinkles.

Still, selling jewelry was and is the company’s true strength, and it was jewelry that formed the backbone for Zale’s unprecedented growth in the sixties. While comprising only 62 per cent of all Zale’s stores after diversification into nonjewelry retail lines, the jewelry division still accounted for 78 per cent of the total profit.

One of the secrets of Zale’s success was its ability to keep innovating. For example, the company brought about a subtle but significant transformation in the basic design of the modern jewelry store by eliminating the long, unbroken glass cases, in which watches blended into bracelets which ran together with rings. Instead, Zale introduced “islands” of cases, which permitted the customer to focus on individual items rather than a glittering undifferentiated array.

Another key to Zale’s growth was the company’s ability to attract and train top personnel. “Zale’s became the West Point of the jewelry business,” recalls one successful former executive. “Anyone who wanted to get ahead in the jewelry business wanted to work for Zale’s. We were the best, no question about it.” Army after army of salesmen, store managers, and executives poured out of the Zale’s training programs and filled the ranks not only of the mother company but also of the independent stores and chains around the country. “Probably one-third to one-half of the people you see running jewelry stores in San Antonio, Dallas, and Houston are graduates of Zale’s,” says one knowledgeable industry source. As one result, Zale’s began to nurture the business that nurtured it: barely a billion-dollar-a-year industry in 1960, the U.S. jewelry trade had grown to $5 billion a year by the early seventies.

Much of this growth, of course, was buoyed by the general spread of affluence during those years; jewelry in general and male jewelry in particular became an affordable new luxury. But Zale’s exploited this phenomenon with an aggressiveness and perspicacity that left its competitors in the dust. As this new affluence brought a flight to the suburbs, Zale’s was quick to spot the trend and seize leasing space in the multiplying new suburban shopping centers. As was and still is the case with other retailers in other industries needing shopping-center space, the company and the developer would often agree to an “exclusive” contract that prohibited leasing space in the same center to another jeweler. Many of Zale’s slower-moving competitors found themselves trapped in the central city where they would often wither and die. (Levit’s jewelers of Houston is currently suing Zale’s and Gordon’s jewelers, which also negotiated “exclusive” contracts, claiming that the contracts amounted to a violation of the antitrust laws and restraint of trade.)

Zale’s also learned to use its size to great advantage. Being the world’s largest retail jewelry chain, the company was often in a position virtually to name its price on large volumes of merchandise. This was especially true when, for one reason or another, a supplier had to unload his goods quickly. At times, Zale’s would be cast in the role of savior, as recently when it picked up several million dollars’ worth of Bulova watches. Other times, Zale’s would be cast in the role of backbreaker.

But, like the military academy to which it was sometimes compared, Zale’s was toughest when it came to its own people and its own internal practices. M. B. Zale’s favorite saying is, “Our people are our greatest asset. We could lose everything tomorrow and build it all back if we still had our people.” But the way M.B. treated his people was, to quote several present and former executives, “like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”

On the one hand, M.B. made sure that he did not create a static organization. Although there was an unspoken consensus that the top positions were reserved for family, everyone always knew there was room to grow and a higher job to strive for. And if anyone had a personal problem, M.B. would attend to it as if the employee were a member of the family. This was particularly true when it came to personal financial problems. Over the years, he and Ben Lipshy made hundreds of thousands of dollars in interest-free loans from the corporate accounts to both family members and regular employees. One nonfamily executive, for example, was lent over $200,000 to cover a stock market loss. Others were lent ten, twenty, fifty, one hundred thousand dollars simply on their word. It is unclear how—if at all—some of these loans were finally paid back.

Salaries, on the other hand, were notoriously low and still are. “The company was built on the backs of the salesmen and the managers,” says a veteran of the phase-two growth years. “They had a lot of people working for $15,000 to $20,000 who could have made $35,000 to $40,000 somewhere else.”

To supplement its low salaries, the company made skillful use of its profit-sharing plan. Each store was assigned a sales goal and its manager was promised a certain percentage if the goal was met; the same system worked on up the organization chart to the top executive level. However, there was considerable flexibility in the way this program was actually administered. If, for example, a good man in a good location simply had an off year because of some extenuating circumstances, he would often get as much profit sharing as he had the year before. Conversely, a manager who turned in an exceptional record might get no more than the standard share with the assurance that “your year will be next year.”

“The new people would get the pie-in-the-sky treatment,” says one Zale’s veteran. “M.B. would point to the senior people at the company and brag about how much profit sharing they had built up. And some of the people who had been with him for a long time really did make themselves millionaires or close to it. Once you’d been around for awhile and had built up a certain amount of profit sharing, it was harder than ever to leave.”

Just as in the old Wichita Falls days, M.B. and Ben continued to work sixteen-hour days six and often seven days a week. Both zealously guarded their health, but their only major exercise, consisted of taking early-morning walks, often as much for thinking as for stretching their legs. Habitually the first ones to arrive at work in the morning, they expected the same sort of singular devotion from their hirelings. Neither touched the typical time-consuming executive sport of golf. Indeed, on one occasion when M.B. learned that the manager of a North Texas store was a devotee of the game, he had the “golf shooter” fired at once.

M.B. was also tough when it came to executive perquisites, or perks. Despite its heavy national and international travel requirements, the company owns no private planes and no company cars. The company pays only for a tourist-class ticket for executives. If an individual wants to fly first class, he must pay the difference. M.B. and Ben, however, always fly tourist. Though their enormous stock holdings make the gesture purely symbolic, M.B. and Ben have always insisted on paying themselves very low salaries relative to their status and positions; the highest either has ever earned is $100,000 a year. The highest salary in the entire company today is only $110,000. This goes to Allen Ginsberg, the company’s resident diamond expert.

“I know it sounds like a Jewish stereotype, but the Zales and the Lipshys have always been tight and they still are,” says one former employee. “It’s not that they’re cheap, it’s just that they happen to be extremely thrifty.”

That, still, is an understatement. Even as the company’s yearly volume swelled into the tens and then into the hundreds of millions, M.B. maintained his practice of checking every invoice the company paid. Though he eventually had to delegate some of the responsibility to others, M.B. will still make periodic invoice checks for a whole month at a time. “You used to get a personal call from M.B. if you so much as bought thirteen light bulbs instead of twelve,” recalls one Zale veteran. “I know because that is exactly what happened to me. The boss wanted to know why I needed that extra bulb. When we would move into new stores, he would always remind me to buy used fixtures instead of new ones. ‘You save five thousand dollars that way,’ he’d always say.”

Similarly, M.B. was never sentimental about closing stores that did not do well. “That’s one of our great strengths,” he has been quoted as saying. “The only thing we’re sentimental about is cash.”

This was particularly true at tax-paying time. Like all other forms of saving, saving on taxes was always a number one priority at Zale. And again, the impetus came from M.B. A citizen of the world, he has never been awed by the divine right of governments to exact tribute. This attitude has been traditional among Jewish jewelry merchants since before they moved the world jewelry-trading center from Holland to Belgium in the wake of a decision by the Dutch to impose a tax on the industry.

One of his most ingenious tax-saving gestures was to develop a unique identity and structure for his rapidly modernizing corporation. The basic idea was consistent with Morris’ vision of his company as being actually two things at once—a unified mother corporation and a loose confederation of independent and self-sustaining individual stores. With the help of a longtime family accountant named Joe Bock (one of Shearn Rovinsky’s predecessors), Morris translated this vision into a legally convenient form known as “multiple corporations,” a structure fairly rare among major retailers. While Sear’s, Penney’s, and McDonald’s, though also composed of a multiplicity of individual outlets, were considered solely as unified corporations, Zale tried to get the best of both worlds. The first 11 stores and the company administration acted as a holding company for the other 1700 stores in the various merchandise chains, which were in turn organized into 1000-odd separately incorporated subsidiaries. At different times and under different circumstances, Zale was one or it was many.

The extra accounting work required to run such a multiple-corporation structure was considerable, which was why most other large retailers avoided it. But the possible tax savings this setup afforded were also considerable, and no one was better at exploiting these possibilities for tax-conscious Zale than the company’s brilliant young chief financial officer, Shearn Rovinsky. Unfortunately for himself, the company, and the ruling family, Rovinsky’s tax-saving schemes often crossed back and forth between the realms of the legal, the extralegal, and the illegal, a pattern of behavior that may ultimately be the undoing of them all.

The legal devices Rovinsky used were clever enough. For example, Rovinsky saved the company some $300,000 in property taxes by having the Dallas real estate upon which the Zale headquarters building sits purchased by the company’s Puerto Rican subsidiary. Similarly, when Zale brought the Light of Peace diamond into the country, Rovinsky saved about $700,000 in U.S. entry taxes by having the diamond purchased by the Puerto Rican subsidiary. Both maneuvers were perfectly legal and brilliant uses of Zale’s corporate structure and the special tax advantages that flow from Puerto Rico’s status as a U.S. territory.

But Rovinsky also devised and maintained several highly questionable tax-saving and cash-payment schemes. One is the practice of paying many overseas employees—including Israeli executives—cash salaries so they can cheat on their foreign income taxes. The company has done this for years and, according to the trial testimony of Donald Zale, intends to continue it in the future. Why? Because in Zale’s view, Israeli taxes are “too high,” and direct payment is the only viable method of retaining “top people” in that country. Asked during Rovinsky’s trial, “Does that tell us, Mr. Zale, that you would bend the rules when necessary to do your business?” Donny answered with a crisp, “Yes, sir.”

The fund that Shearn Rovinsky set up to handle these and other curious transactions has come to be known as the “Belgian fund” because of its location in the benign tax climate of Antwerp. But proceeds from the fund were also used in the United States. During the Rovinsky trial, Zale admitted making some $25,000 in illegal political contributions to undisclosed U.S. politicians with money from the Belgian fund. The company insisted the donations stopped in 1972. A ledger produced at the trial also showed that numerous withdrawals for unspecified purposes were subsequently made by M.B., Ben Lipshy, Donald, and Donald’s brother Marvin with the largest and latest withdrawal being $175,000 to Marvin in late 1975, just a few weeks before Rovinsky’s demise.

Zale also admitted during the course of the Rovinsky court proceedings that the company’s Sugerman division, a San Antonio-based military insignia supplier, made unspecified “gifts” of Zale merchandise to certain unnamed military post exchange buying agents in the late sixties and early seventies. The company said that upon discovering the “gifts,” top management stopped them and made it known that anyone continuing the practice would be terminated. However, Rovinsky now claims that top management was in on it all along. He says that at Donald Zale’s request he created a fictitious customer named “Sol Jackson” to whom the merchandise was billed. Donald Zale proposed the name Sol Jackson, Rovinsky says, because he knew that Rovinsky—whose full, name is Sol Shearn—hated the name Sol.

Of course, neither the Belgian fund nor the “gifts” to the buying agents are terribly unusual in the corporate world, and the crisis at Zale would not be so severe had Rovinsky’s projects ended there. But they did not. Instead, as he told the judge in his first trial, Rovinsky went on to devise a series of tax-evasion schemes, ranging from the simple underreporting of inventory value to complex but improper deferments of profits. By far his most ingenious ploy was a tax “misallocation” scheme designed to save money on what was known as the surtax exemption. The essence of the scheme consisted of “switching” the profits of high-income stores—the “winners”—with the losses of poorly performing stores—the “losers”—to minimize the number of stores showing a profit of more than $25,000 in a year. Under the surtax provision the stores would be taxed at a reduced rate of 28 per cent, like a small business, instead of at the regular corporate rate of 48 per cent, which applied to stores with over $25,000 profit. The key to Rovinsky’s scheme was moving the profits of stores which made over $25,000 a year into stores which suffered net losses. Some measure of the tax-saving potential of this plan can be gleaned from the knowledge that the actual profits of Zale’s stores range from the $15,000-to-$20,000 level of its discount stores to the $250,000 level of its Corrigan’s stores, a spread which leaves plenty of room for beneficial “misallocations.” Eventually Rovinsky systematized his switching scheme with the help of the company computer.

About the basic outline of this “misallocation” plan there is relatively little substantial disagreement between Rovinsky and the ruling family. The dispute is over how extensively and with whose knowledge and authorization these schemes were conducted. Rovinsky claims that the practice began on a small-scale way back in 1960 after a run-in with M.B. over the way the tax returns were being handled. According to Rovinsky, the old man in checking the returns had complained that Rovinsky had listed a recently acquired store as having been acquired at a taxable profit, which, because of the value of the store’s inventory, was in fact the case. Rovinsky quotes M.B. as saying, “ ‘The way I look at this, this is one company. I don’t understand why one of my stores has to show a profit when my Phoenix store is losing money. As smart as you are, you ought to be able to figure something out.’ ”

That summer, when Zale acquired a store in Canton, Ohio, at a profit, Rovinsky “moved the profit” into the Phoenix store.

“Canton, Ohio, was the first store where we buried the profits, and there were many more from 1960 through 1964,” Rovinsky says. “Every time we made an acquisition, we made a profit. It was all examined in detail by M.B.” In 1970, as the surtax exemption was being phased out by the government, Rovinsky reasoned—on the basis of his own IRS special agent experience—that government auditors would not give much attention to surtax matters and concluded the time therefore was ripe to use the computer for a refined company-wide “misallocation” scheme.

By this time, he says, Donny and Ben and several others had become party to the knowledge of what he was doing and smiled upon it and other schemes. Rovinsky claims when he first showed Donny his computerized version of the “misallocation” scheme, Donny noticed a Corrigan’s store that usually made $250,000 profit had been listed at only $25,000 profit and told Rovinsky, “This is fine for tax purposes, but I need the emis to run this company.” Henceforth, Rovinsky says, the company kept two sets of books: one for tax purposes, and another for running the company. The latter set, Rovinsky says, he and other family insiders called “the emis.”

Aided by computer technology, switching the profits and losses of “winners” and “losers” became easy fun. “We didn’t consider tax evasion a crime,” Rovinsky recalls. “It was just a big game.”

Rovinsky estimates the “misallocations” resulted in a total tax savings of $8 million. He says the total tax liability with penalties for that and other schemes he ran is about $50 million—conservatively. His allegations have received at least partial support from the testimony of his two assistants, Joe Underwood and Ronnie Hickerson, who admitted participating in the “misallocation” scheme since 1971, but said they did not report it to Donny and Ben because “that was Shearn’s job.” Neither man was fired. In addition, two former high-ranking executives of the company who did not become involved in Rovinsky’s trial proceedings have said in interviews that “at least twenty” top people in the corporation were aware Rovinsky was falsifying the company’s tax returns; there was, say these sources, a “standing joke” about which set of books the company would show when the tax men came.

Meanwhile, the corporation itself has admitted to $4 million in potential tax liability as a result of the “misallocation” scheme, a figure which admittedly covers only the last four years of Rovinsky’s tenure. But while acknowledging an “underpayment” of taxes may have occurred, M.B., Donny, and Ben all deny ever knowing about the “misallocation” scheme or any special computer printout for the purpose of tax evasion, and claim further that any improprieties that may have occurred ended with Rovinsky’s dismissal.

They say Rovinsky devised and authorized the tax dodge schemes entirely on his own. He had demonstrated his brilliance as an accountant and they had complete faith in his honesty and ability. They claim that the only computer printouts they saw were ones which accurately reflected the profits and losses of their stores. They say they did not review the printout Rovinsky devised for tax purposes or compare that one with the printouts they used to operate the company, and add that by the time Rovinsky began to perpetrate his illegal schemes, Zale was too big and had too many subsidiaries for M.B. or anyone else to check everything. Taxes, according to the ruling family, were Shearn Rovinsky’s responsibility. “Everybody’s been asking us about the emis” Donny said in a recent interview. “I never heard that word used for one of our printouts until the trial.”

This dispute will eventually have to be settled by the IRS and the courts, but as the corporate family well knows, there is almost no way Zale can emerge unscathed. If charged and found guilty of criminal fraud, the Zales and the Lipshys could face not only further disgrace and humiliation but also stiff fines and prison sentences. Even if they are not held responsible for the actual commission of crimes, the corporate family still stands to lose severely. Just as Rovinsky’s theft trial led to a host of apparently unrelated disclosures about Zale’s questionable activities with the Belgian fund, these allegations about the tax schemes could lead to still further embarrassing disclosures about other areas of company behavior. “Rovinsky’s charges are just the tip of the iceberg,” claims one former employee who had working access to the company’s books.

Whatever the emis really is, both sides agree that this period in the company’s history is filled with other examples of the tension between the family ways and the ways of the outside world, between tradition and modern corporate life. Perhaps the best sign of the times was the move from the old two-story building on Akard Street to the glittering bronzed-glass eighteen-story headquarters building on Stemmons Freeway. Set at a special angle to the freeway, on a cul-de-sac appropriately named Diamond Park, the great toaster-shaped edifice is a prideful sight in the morning sun as it shimmers from gold to black and back to gold. But it is also the symbol of some significant changes in the corporate family and its leadership.

In 1971, as he was approaching the “mandatory” retirement age of seventy, M.B. moved from chairman of the board to chairman of the executive committee, leaving Ben Lipshy to take his place. Donny Zale, Marvin Zale, their cousin Leo Fields, and Marvin Rubin, the highest-ranking nonfamily member, were instructed to choose a president from among themselves. Though only the second-oldest of M.B.’s sons, Donny, then 37, won out.

Donny reacted to his new responsibility by becoming more tough-minded and somewhat more daring. One of the first assertions of his leadership was to change the very nature and identity of the Zale’s store. The stores had been typical discount credit jewelers selling pots and pans and appliances alongside bracelets and rings. As Gordon’s and other competitors determined that their clientele had become affluent enough for them to abandon the sale of these “traffic” items and become “jewelry boutiques,” Donny decided Zale’s, too, should become a pure specialty outfit for fine jewelry, “the diamond store,” as the company’s advertisements now say. “The decision was obvious but it took some balls to get it implemented,” Donny said recently, looking back. “The decision to go into diamonds involved dropping about 20 per cent of our business. That’s a hell of a risk.”

These and other moves Donny made did pay off, but many company insiders who had been loyal to M.B. and to Ben Lipshy found Donny too concerned with proving himself, not only in charting new directions but also in handling people. Much of it they describe as Donny’s overreaction to the company’s increasing size. He always had to make it clear he was the boss, that he had 17,000 employees depending on him for their livelihood, that he could not be the same old Donny anymore. “M.B. and Ben were hard but compassionate,” says one Zale veteran. “Donny was just hard.”

The same was said about another family member who joined the top executive ranks in the early seventies, Ben Lipshy’s son Bruce. Though born in Wichita Falls, Bruce was a child of Dallas and a graduate of SMU. He did not start out working in a jewelry store like his father, his Uncle Morris, and his cousin Donny, but went to law school and became one of the founding members of a prosperous Dallas law firm before deciding to join the Zale Corporation in 1972. When he came, at 29, he began as senior vice president.

Not surprisingly, Bruce quickly developed a reputation for being arrogant and impetuous, a kid who had gone too far too fast. Like his cousin Donny, Bruce seemed constantly concerned with proving himself. Symbolically, an assistant once gave him a poster, which hung in his office, titled “The Prince” after people around the building began calling him “Prince Bruce.” Then he picked up the nickname “Mr. Impetuous” for his tendency to snap at decisions and people. Bruce faced other personal problems as well. Short, stocky, and frenetic, with handsome features and enormous green eyes, he gained a reputation as something of a ladies’ man. His standing was not enhanced by a bitter divorce proceeding in 1975 in which he accused his wife of adultery and invoked all the powers of the corporate family, the local rabbinate, and even presumably confidential psychiatrist’s files to aid in his custody fight.

But at the corporation, Bruce and Donny began to assert, at least something of a modernizing second-generation influence on a company with one foot in the past and the other now firmly in the present. Though the executive committee of the corporation still held its official meetings over lunch at M.B.’s apartment, the coming of Bruce and Donny signaled a new and more impersonal management style. M.B. began to stay away from Diamond Park and devoted his energies to foreign acquisitions, while the others began an increasing reliance on management systems and procedures.

As Bruce and Donny and their corporation grew in stature and sophistication, so did their chief financial officer, Shearn Rovinsky. On the surface, Rovinsky seemed a picture of success. He won considerable public praise from his peers and his employers for his apparent magic as a taxman, but he also distinguished himself in other areas. He saved the company $200,000 a year in overhead costs by integrating the accounting systems. He developed a highly accurate cash flow forecasting system and was instrumental in obtaining an A-1 rating from Standard and Poor and a Prime I rating from Moody’s. Such ratings pave the way for a corporation to raise money by selling commercial paper to the public. In the tight-money days of 1974 and 1975, the company was thus able to draw on a cash reserve of some $75 million Rovinsky had built up through such sales.

Rovinsky himself was often the first to list these accomplishments, boasting that he was the best accountant west of the Mississippi and east of Jerusalem. But beneath his prideful facade, Rovinsky was a strange and troubled man, a tightening knot of opposites. His delicate build and propensity for almost childlike gestures, expressions, and postures conveyed an impression of weakness. He could sit cross-legged on the floor, simper like a schoolboy, or frown and flail his arms like a bad-tempered brat. He was a follower, not a leader. He craved acceptance in the Zale-Lipshy inner circle and worked hard to get it. He was gullible and trusting to a fault. But at the same time, he was sly and devious, capable of deceiving everyone from his employers and the IRS to his wife and family. Despite occasional diffidence, he was full of sharp prejudices, and he retained a bitter sense of personal superiority over those whose favor he sought. Perhaps more than anything, he was a character of the Walter Mitty style, a fellow who bounced from one fantasy world to the next. The only constant for him was numbers.

As Rovinsky’s corporate success increased, he began to make his separate dream lives into separate realities. He began to wear shiny silk suits and flew first class on business trips instead of tourist class like M.B., Donny, and Ben. Privately he disdained them for what he called their “Jewishness.”

Always drawn to the mathematics of games of chance, Rovinsky became ever more obsessed by the dream of quick, easy money and began to gamble heavily. He kept a television in his office to watch the sporting events he bet on and held what some have called the “biggest poker game in Dallas” at his house on Yamini every Tuesday night. He would later testify that he bet approximately $50,000 with a net loss of about $150,000 between 1971 and the end of 1975.

In addition, Rovinsky spent plenty of money on his family during these years. He sent his four children to private schools, helped put on a $20,000 bar mitzvah for his son Kirk, installed a pool in the backyard, and supplied his wife, Linda, with tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of clothes and jewelry.

Unbeknownst to his family and most of his friends, Shearn lavished thousands more on his girl friend, Shari Oliver, who was simultaneously having an on-again-off-again relationship with Bruce Lipshy and several other boyfriends. Typically, Rovinsky lost his head over his new lover. He bought Shari new clothes, fine jewelry, and a Pontiac Grand Prix, paid the rent on the North Dallas townhouse apartment she shared with her seven-year-old daughter by a previous marriage, and took her on trips to Las Vegas.

Strangely enough, no one seemed to wonder where Shearn Rovinsky was getting the money to finance his swinging new lifestyle, perhaps because only Rovinsky himself knew about all the fragmented sides of it. His wife, an heiress to a blue-jeans manufacturing company, had some money, but she was not all that wealthy, and Rovinsky’s take-home pay was only about $50,000 a year. Still, he was depositing hundreds of thousands of dollars in his accounts at Republic National Bank every year and spending the money fairly visibly and with speed. And despite his huge depositing, his personal bank account was almost constantly overdrawn, but with no apparent alarm to his bankers or to anyone else. “I always thought we were rather conservative,” Rovinksy’s wife, Linda, would remark after her husband’s fall. “Most of the money we spent was my money, but I was never consulted on anything.”

Finally, in late January 3976, the high times came crashing down. The beginning of the end came when Rovinsky’s assistant Ronnie Hickerson stumbled across an irregular entry on the Zale Corporation books: one of the property tax accounts showed that $30,000 had been paid out. This was unusual because debits to the property tax account were typically odd-numbered figures like $5,768.95; property taxes were never nice round numbers like $10,000, and they were never quite that high. Further investigation revealed that the $10,000 had not been paid as a property tax expense: it had been withdrawn by Shearn Rovinsky. When Hickerson and his assistant Joe Underwood confronted Rovinsky with the entry, he kept giving them double-talk. First, Rovinsky said that the money was connected with a commercial paper transaction and that a check had been deposited to make up the balance. But Hickerson and Underwood discovered that story to be a lie when they learned that Rovinsky did not deposit a check to cover the $10,000 until after they had confronted him about the irregular entry.

Confronted a second time, Rovinsky did something his two assistants had never seen him do before: he broke into a cold sweat. He told Hickerson and Underwood that the money was “for political” and made it known by his stern facial expression that the matter should be dismissed. Hickerson and Underwood were not satisfied. The massive tax “misallocation” scheme they had been participating in for years had never prompted them to report to Donald Zale, but Rovinsky’s inability to explain this curious $10,000 entry did. It appeared that Shearn might have had his hand in the till. A week-long investigation of company accounts by Hickerson and Touche Ross & Company, Zale’s outside auditing firm, eventually determined that over $600,000 was missing. After a series of hotly contested private meetings with Donny and Ben, Rovinsky was given 24 hours to come up with a satisfactory explanation.

When Rovinsky went home on the fretful night of February 5, he got a telephone call from his brother-in-law Larry Burk, a Lipshy son-in-law not employed at Zale Corporation. “I understand you’ve committed some horrible misadventures,” Burk jibed. Apparently, the word on him was already out. Shearn slammed down the phone without replying. “It sounds sort of silly,” he would recall months later. “But that’s when I decided I was going to have to kill myself.”

No doubt both Rovinsky and the Zale people have at times wished the suicide attempt had been successful. For when Rovinsky came back from his flight with Shari Oliver to face the first set of theft charges against him, he and the Zale family began a legal battle which appears destined to continue until one or both are totally destroyed. The great shock so far is that round one—the first trial on theft charges—went to Rovinsky.

Having already convinced the Dallas County district attorney of the nobility of their enterprise, the Zales and the Lipshys apparently expected to march down to the courthouse and convince the jury, too. But Shearn Rovinsky turned out to be a marvelous witness on his own behalf, with his photographic memory spilling out detail after colorful detail. He claimed that part of the $600,000 he had taken was for political contributions made by his superiors. The rest, he said, was “secret compensation” for his work on the company’s tax evasion schemes. When the trial judge ruled Rovinsky could not claim one illegal act as a defense against charges of committing another, Shearn modified his story to say the money was “loans” against a $2 million stock award Ben and Donny had promised him. Rovinsky’s attorneys then pointed accusing fingers at Zale; in cross-examinations they concentrated on the family’s own record and the questionable activities they admitted authorizing Rovinsky to pursue—the Belgian fund, the $25,000 in political contributions, and insider loans.

Ben and Donny, on the other hand, were terrible on the stand. Though their own well-known penury was perhaps the best counter to Rovinsky’s claim of a $2 million stock award, they hemmed and hawed and claimed to know so little about their former chief financial officer and the way the company’s accounts were handled that it seemed a wonder they could even sell a watch, much less run a great multinational corporation. Though by no means convinced of Rovinsky’s total innocence, the jury apparently felt that he was at worst just one rascal among many and should not be made to suffer while his masters got away. They voted to acquit.

The impact on the Zale corporate family was devastating. A clan that had built its business and its reputation on honor and integrity—mazel und brucha—had had that honor and integrity seriously impugned not only by a disgruntled former employee but also by the legal process. And more was yet to come: already stirred up by Rovinsky’s pretrial allegations, the IRS, the SEC, and three groups of outside shareholders were sure to crank up their separate attacks with renewed vigor and credibility. In the meantime, to add insult, the bonding company that insures Zale against theft up to $5 million made it known that they had no intention of reimbursing the company for the $600,000 Rovinsky had been acquitted of stealing.

Characteristically, the family attempted stoicism and restraint: shortly after the verdict was announced, Donald Zale came out of his office, turned to a trusted employee, and simply quoted the cliché heading printed atop his Uncle Ben Lipshy’s memo pads: “When the going gets tough the tough get going,” then he addressed himself to the details of some routine jewelry transactions. But it was not easy to maintain the front for long, especially not for the older generation of family leadership. For weeks afterward, M.B. Zale wandered around the offices, thinking aloud, “Where did I go wrong? After fifty years, what was my mistake?” And for the first time in their living memories the women of the family feared what would happen the next time they showed their faces in public.

The reaction in the Jewish community was fascinating. A respected member of the rabbinate expressed the apparent consensus when he wondered aloud, “How could Morris not have known what Shearn was doing? This is what everyone cannot understand. Perhaps it is a symptom of size—that one man cannot control everything the way he used to.” Among local Jewish businessmen, the reaction was harsher and more cynical. “Frankly, the last place you expect a Jewish businessman to get beat is on the books,” said one, “especially when it’s people who watch the books as closely as the Zales do. The worst part of it is that they let themselves get caught by turning themselves in. That implies a serious error of judgment. No matter how bad things are, you just don’t blow the whistle on your accountant, because he’ll always have something on you, no matter how honestly you try to run your business.”

Exactly when Zale’s officers will do their explaining to stockholders remains to be seen. Because the SEC finds the company’s proxy statement “inadequate,” Zale has been unable to hold an annual shareholders’ meeting for over a year and a half, and there is none scheduled for the near future.

Apart from the questions directed at Zale, Rovinsky’s acquittal and the allegations he made before, during, and after the trial also raised serious questions about the behavior of Touche Ross & Company, the IRS, and Republic National Bank. How had Rovinsky been able to mislead them for so long? Why had they not been able to discover the irregularities, his tax evasion schemes, his profligate spending? Rovinsky’s answer was that Touche Ross had “winked at” his tax evasion schemes and that lie—the former IRS special agent—had simply used his wiles and experience to convince the IRS that the company’s books were in order; he still does not know why the bank did not inquire into his incessant overdrafts. Meanwhile, Touche Ross, the IRS, and Republic National Bank all refuse to comment on the case.

Then came round two. Shortly after Rovinsky’s acquittal, he and Ben Lipshy met in a series of face-to-face sessions at the Fairmont Hotel in downtown Dallas. At issue were three points of contention between Rovinsky and Zale: a $55.5 million civil suit the former chief accountant threatened to file against the corporation and the family; the extent to which Rovinsky would cooperate with the shareholders suing Zale or with media people researching stories on the company; and, of course, Rovinsky’s testimony to the IRS. Although stressing he wanted to structure their agreement “legally,” Rovinsky said his cooperation on this third area would have to be unwritten because “it might be obstruction of justice.” Rovinsky said that he could shade his testimony either to exonerate the family or to implicate them in tax fraud.