These Indians told us a very strange tale. They said that fifteen or sixteen years ago there wandered about the country a white man of small stature and with a beard whom they called Bad Thing . . . and whenever he would approach their dwellings their hair would stand on end and they began to tremble. . . . That man thereupon came in and took hold of anyone he chose, and with a sharp knife of flint, as broad as a hand and two palms in length, he cut their side and, thrusting his hand through the gash, took out the entrails, cutting off a piece one palm long, which he threw into the fire . . . Then he placed his hands on the wounds, and they told us they closed at once.

— La Relación of Cabeza de Vaca, 1542

Three centuries after Cabeza de Vaca, Uncle Fox Tatum put each of his feet into a bucket and set forth to stroll across the surface of Hendrick’s Lake. But certain natural forces Uncle Fox had not taken into account began to assert themselves. He teetered for a few seconds before falling forward into the lake where, with his feet still caught in the buckets, he almost drowned.

But Uncle Fox was undaunted. He was a technological visionary who believed that, given the proper hardware and imagination, humankind could transcend itself. Accordingly he turned his attention to the mastery of another element. Circa 1860, he stood on the second floor of his house and stepped out into the void trailing a homemade parachute. He broke both his legs.

Uncle Fox’s hubristic flights were definitely suborbital, and it’s probably best not to project them into the expanded possibilities of our own time. Still, I wonder how his faith in progress would compel him to react if he were around today to meet the advance glad-hander from the power company: “Uncle Fox, we’re gonna scrape away the first fifty feet or so of your land, haul away a mess of unsightly congealed prehistoric swamp components, fill in the holes, and fix everything up again so’s you won’t know the difference!”

Maybe we should be grateful that Uncle Fox is no longer here to give his approval, to witness his eccentricities fulfilled on such a mass scale.

But whether Uncle Fox, lying now in sanctified and unleased ground, knows it or not, strip mining is coming to Tatum, the town that bears his name, as it has come already to five or six other Texas communities, as it will come eventually, barring a deus ex machina like solar energy, to a great swath of land that runs intermittently from Texarkana to Laredo, land that is nesting above 10.4 billion short tons of strippable lignite and another 100 billion tons too deep to be strip-mined but which could feasibly be recoverable. There is enough fuel here to keep the whole U.S. for another thirteen years in the style to which it has grown accustomed.

Lignite is coal, a low-grade, lackluster coal, not quite primordial goo but several steps below bituminous coal, the industrial standard, and far from the ivy league glossiness of anthracite. Lignite is to coal as Peking man is to you and me, but the people who are after it are not evolutionary elitists. Though it has, on average, probably only half the Btu’s (British thermal units—a measure of heat energy potential) per pound that bituminous coal does, it has a low sulfur content and it burns.

I have a piece of lignite here on my desk, and though it is a little dried out and bleached by exposure to the sun, it should serve for demonstration purposes. In its natural state, lying compressed and content beneath the earth in a glacier-like seam, this piece of lignite would be softer and more malleable. (Here on my desk it’s grown brittle and flaky—I think it’s pining away.) Held up to the light, lignite wavers in color between a flat black and a very drab shade of brown: it’s not “coal-black,” but it speaks with a certain organic authority. Its surface is splintering into what I read are “subconchoidal” fractures, and this gives it the look of tree bark, a fitting analogy since this piece of lignite began its afterlife many millions of years ago as a pile of compressed flora in the remnants of a moldering swamp.

Lignite is hardly a new discovery. Early settlers to our state discovered that lignite shoals made natural crossings on the Sabine River. A French cartographer named L’Hertier reported witnessing charbon de terre mined in East Texas in 1819, and by 1950, 150 lignite mines had been in operation. The coal was deep-mined until several decades ago when the rooting instinct found its technological form. The obvious, ungracious method of strip mining that proved efficient in Appalachia moved into Texas on a blessedly small scale.

That was before the energy shortage. Now big-time strip mining in Texas has taken the increasingly shorter jump from feasibility to inevitability. The power companies are giddy with the sense of mission: lignite will break the back of the OPEC cartel and give the United States a reprieve from all this doomsday talk, strip mining will unleash the lignite, and land reclamation will put the earth back like it was.

By far most of the lignite mining in Texas today is being done by Texas Utilities Services (TUS), a subsidiary of Texas Utilities Company, a holding company consisting of three regional power entities: Dallas Power and Light, Texas Electric, and Texas Power and Light—a “cartel” that serves a third of the people in the state. The power generated by TUS through the strip mining of East Texas immediately wafts away to TUS’s clients in Dallas, Fort Worth, and other more westerly Gothams. Southwestern Electric Power Company (SWEPCO), the power company that serves East Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas, is in the process of converting from gas to coal-burning generators and is leasing all the anointed ground in Northeast Texas they can find.

But for now, TUS is who to watch. It is a shrewd company with a keen ear to the ground: it heard the rumblings of environmental concern early. Long before the mood of its constituency had ossified into legislation, TUS began planning how to set things aright. At Fairfield, 85 miles southeast of Dallas, the site of its first operation, it began reclaiming land five years before a new state law requiring it went into effect this year. It may not even be out of place to grant TUS a sort of prehensile conscience. Even people who consider strip mining an abomination and reclamation an act of cosmetic arrogance are impressed with the company’s environmental attentions. TUS remains a paradox, an ogre with a heart of gold.

Tatum is a tiny community, twenty miles from Longview, nestled within the imaginary borders of an area the forces of boosterism have labeled Opportunity Valley. The city limits sign indicates a population of 694, but, with the influx of construction workers building the generating plant that the coal will fuel, Tatum’s inhabitants now number closer to 1100. There is not enough housing in Tatum for all the workers, and those who haven’t found a place in one of the new mobile home parks commute from Longview or Henderson.

The land at Tatum is pine forest and pasture, and the ground rises into low hills in anticipation of the long upward grade to the Ozarks. This used to be cotton- and corn-producing land, but those who still work it use it for timber and grazing.

At one time Opportunity Valley was a part of the great confederation of Caddo Indian nations. In the sixteenth century, when the Caddo culture declined, the land passed to a succession of Indian tribes, most—like the Creeks and the Cherokees—migrating westward, until white colonists came down from Arkansas on an ancient Indian thoroughfare renamed Trammel’s Trace after a white horse thief. It was on this trail that Davy Crockett and Sam Houston are said to have come to Texas. The Trace exists today as a boundary road between Rusk and Panola counties before it disappears into Martin Lake, TUS’s brand-new reservoir for cooling water from the generating plant.

Mining in Tatum is expected to begin in May. A dragline—the machine that does the actual earth removal—is being pieced together a few miles out of town, and on the shores of Martin Lake the generating plant waits placidly for something to ingest.

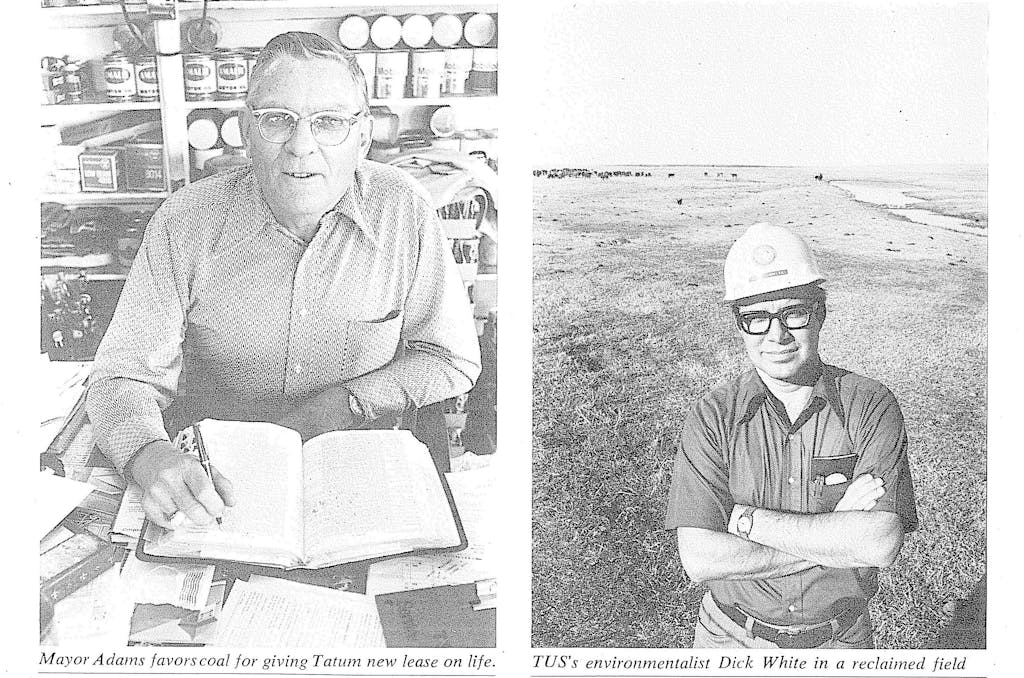

I have come to Tatum with my environmentalist knee-jerk reflexes set on a hair trigger, ready to bear witness, Steinbeck-wise, to the ravaging of ancestral land by the ruthless shock-troops of big business, to record farmers attacking great earth-gulping machines with their shovels. My first stop in this enterprise is Adams Texaco Station, where Murray Adams, mayor of Tatum, sits behind his desk chewing on a cigar and occasionally spitting some vile substance into a motor-oil box filled with pecan shells.

“Naw,” he says, “I hadn’t heard of anybody that’s against it. It’s helped our town, it’s helped our community, our county, and our school. Where this recession or depression or whatever has hit lots of little towns, we just ain’t had one.”

He says this with the canny detachment common to both his professions, and regards my interest about strip mining with what I interpret to be a mild puzzlement. He has every reason to be suspicious of my motives; TUS has indeed done a lot for his town: the school board and the county will be taking in hundreds of thousands of dollars in tax revenue from the power plant, its construction creates jobs and raises property values, and there will be a state park on Lake Martin if TUS and the Parks and Wildlife Department ever come to terms over where and how large it should be.

And that’s not even taking into account the benefits to the individual landowner who has leased the mineral rights to his acreage. Here’s What You Get: $300 per acre-foot mined, 20 cents per ton of lignite extracted, reimbursement for surface damages, and the company’s word, now backed by law, and the law now backed (perhaps a little dubiously) by the Texas Railroad Commission, that the land will be returned “to its original or other substantially beneficial condition, considering past and possible future uses of the area and the surrounding topography.” (These are all TUS figures; other companies have slightly different lease arrangements, and the actual amount of the contract will vary with the individual, depending on how much the land is needed, and on how long the landowner held out.)

All of this means, of course, that if you can avert your eyes while your land is shoveled up by a machine that weighs five million pounds, that if you don’t mind taking a sabbatical for two to five years and returning, check in hand, to see how the Good Fairy has transformed your land into something crisp and new and in a “substantially beneficial condition,” then you stand to make a lot of money.

“If somebody’s got enough coal under their land,” says Mayor Adams, “and if they can get two thousand dollars an acre for it, they’d be foolish not to let them mine it.”

Not many people in Tatum are that foolish; not many can afford the luxury. According to one well-informed resident, virtually the whole area from Tatum to Longview is leased up, including most of Tatum itself, and although Mayor Adams doubts it will happen, it is not inconceivable that some years hence, what is now downtown will be down under.

But it is time to see this phenomenon firsthand, and so I drive up the highway a few miles toward Darco, the site of a surface mine that has been operated by a series of companies for the production of activated carbons and charcoal for twenty-five years. As I pull out of Tatum the site is just visible in the distance, an almost hallucinatory outcropping on the horizon, a pygmy mountain range the color of steel.

Further on, the roadside undergoes some modulations subtle enough at first to escape notice. But soon the land is clearly different: the terrain has become abrupt, and past a suspiciously regular stand of young pines I can see a landscape consisting of odd low hills connected by twisting gullies. At first I mistake the hills for remnants of Caddo temple mounds, but they are obviously monuments of a different sort, the heritage of the pre-reclamation era.

The mounds are composed of “overburden,” the soil that was removed to expose the lignite seam and left where it was shoveled aside. I have a taste for spectral landscapes, and find myself rather attracted to this earth sculpture hiding behind the pine fence. But a mile or so down the highway there is not much latitude of response available. Here, down a dirt road, past a No Trespassing sign, the delicate webbing that holds cold beauty apart from cold-bloodedness begins to disintegrate.

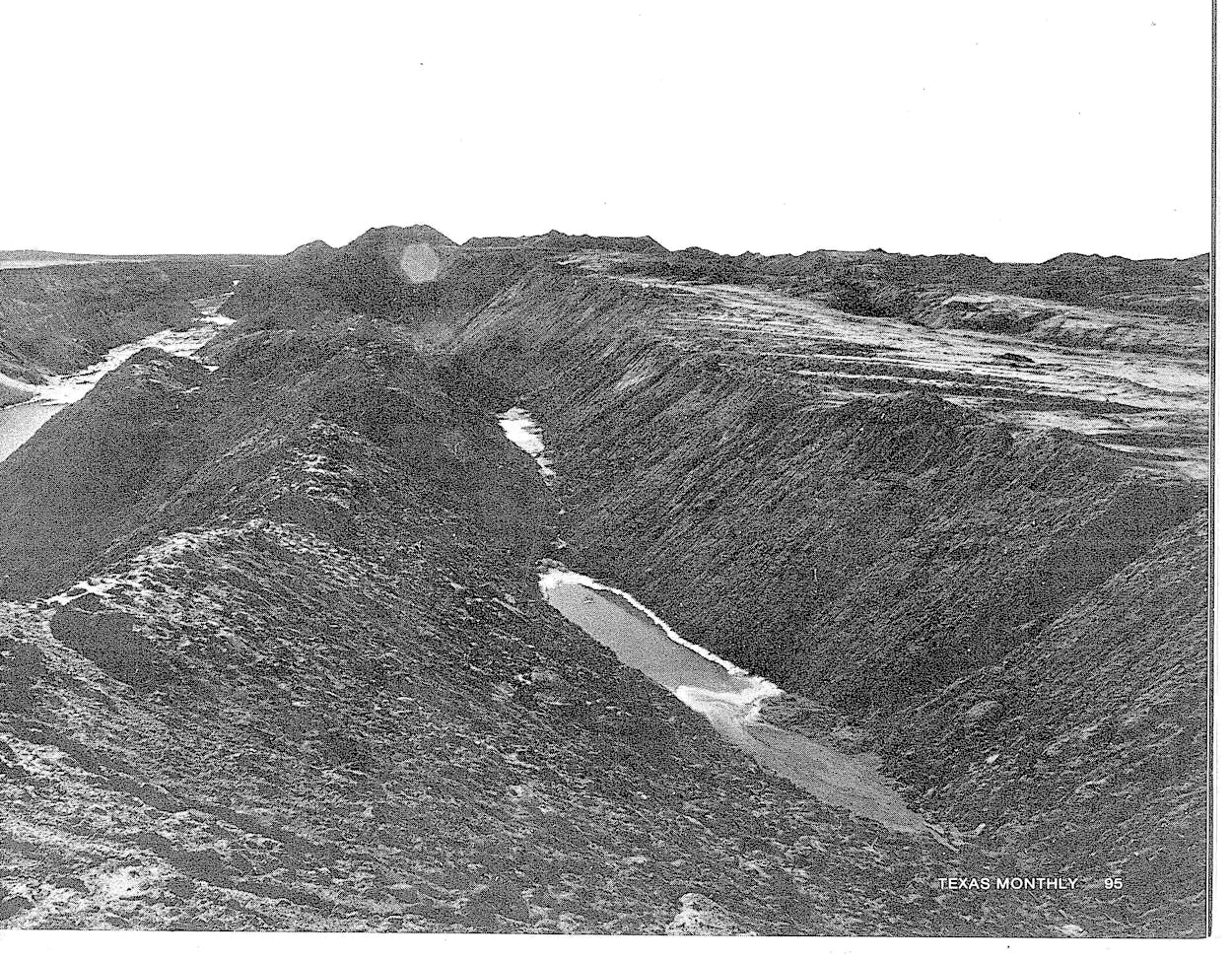

I know this is standard rape-of-the-environment stuff, but look: the road goes on and plunges into an ash-blue valley set between two sterile overburden walls, and goes on to forge a desolate canyon all the way to the horizon. It is all below the perception of color: whatever tones this vista possesses do not engage the rods and cones of the eye, neither does its vastness assimilate as proportion in the brain. No, it’s too much. It doesn’t square with our world.

But I’m getting carried away. It’s really not that bad, folks. Even now the land is in the process of being reclaimed. Bulldozers have smoothed and contoured some of the overburden, and from these areas blankets of grass the exact shale color of this morning’s sky are sprouting. Pine seedlings, sparse and fluffy, cover the distant hills like down. Petrified logs dug up by the dragline loom picturesquely about, freed from millennia of entrapment but with no place to go. If you look up to the sky you can almost see, as if in one of those New Deal propaganda posters, the hand of man shaking the hand of God.

In Tatum, where I spend that afternoon and the next morning soliciting opinions, the reaction to the coming strip mining is low-key, just as Mayor Adams predicted. What outrage there is in this town resides in some of the people whose land was condemned for the creation of Lake Martin and who were forced to sell to TUS and move off. But a company cannot condemn land for mining: it must buy the surface rights.

“Really, I’m for it and against it,” Troy Williams says. “I grew up here and I like it here and I wish it’d stay like it is.

“Ninety-nine per cent of the people, when they come in and tell you they’ll let you keep your land and give you two thousand dollars, well they’re going to go ahead and do it.”

Williams has a garage on the edge of Tatum’s “ghost town,” a block-long stretch of empty buildings perpendicular to the railroad. He seems vaguely out of place here, with the wavy blond hair and wistful blue eyes of an aging enfant terrible in a local country band. Williams has inherited 100 acres of land, 77 of which his father leased for coal before his death several years ago. Williams admits that he’s not too happy about it, but if it were up to him he’d have done it himself. It was just too good a deal.

“The way I understand it they’ll put it back any way you want it. They’ll plant pine or clover, anything you want. Personally, I don’t feel like it could be put back the way it was. We’ve got twelve or fifteen ponds on the place and some big old trees a hundred years old I wouldn’t take a thousand dollars apiece for.

“Yeah, you might have one man out of a thousand who’d refuse to sell his land, but I ain’t heard of anybody.”

Neither have I. There are plenty of people who haven’t sold yet, but most of them are holding out, waiting for the ante to go up. Strip mining, the idea of it, gives a slight bittersweet cast to Tatum’s boom, but it’s not that big a problem. The cattle market is down, farming is a thing of the past, what else is there to do with your land? Look at it?

“I’ll tell you my opinion of strip mining,” Melton Turlington says. “You’ve got unpopulated sections of the United States where it takes thirty-five or forty acres to support a cow. Hell, let ’em strip-mine that! It’s not doin’ anybody any good. But I’ve got an eleven-year-old boy and three grandchildren, and if they start strip-mining this land around here they’ll be sorry for it some day.”

Beneath his suede and rakishly applied cowboy hat Turlington levels a stare at me with a set of finely tuned blue eyes. He is holding forth in Mike Dragisic’s drugstore where he has come to fill a prescription. Dragisic himself, a pharmacist from Longview who has already explained to me how leasing his land to SWEPCO helped him buy his store, leans over the counter and listens.

“But what’s people gonna do for energy?” Turlington goes on, getting himself swept up in every facet of the question, like a man trapped in a revolving door. He hasn’t leased his land yet—he hasn’t been approached yet—and in his case it seems that fatalism and not pure economics will be the major factor in his decision to do so.

“If I leased it or sold it I’d move out of this part of the country. What’s the point in me staying here with a strip mine all around me? Why should I sit around and watch where I was born and raised butchered when I can take a hundred thousand from Texas Utilities’ and go live in Colorado somewhere?

“But people need, energy. You know I’m not very smart—I’m a country boy and I had a little junior college. I read suggestions that they put this stuff in rockets and send it to the sun to get energy. But that’s just too deep for my head. A man can really get to thinkin’—and I mean soul searchin’— and still not know what to think.”

Turlington reminisces about the days before Texas Eastman and all the other industry moved into Longview, 25 miles up the road. He claims that the Sabine, now muddy and opaque, used to run clear when he was a boy.

“I like to hunt and I like to fish and see things grow. You can’t have all that and have this going on too.

“Now you don’t see nothin’ when you look out this here drugstore window. But goddam, I see forty-six years out there! That’s home!”

“Ah hell,” says Louis Austin, “the world has been ecologically unsound ever since Adam first wee-weed in the stream.”

Louis Austin is chairman of the board and chief executive officer of TUS, a trim man in a trim dark suit whose gray hair is cut in one of those perfect crew cuts you used to see pictured in the Butch Wax ads in Boys’ Life. We’re sitting in a south Austin motel room, and he is presenting me with a card graphing the “World’s Ultimate Supply of Fossil Fuel and U-235.” The message of this graph is that coal is the United States’ greatest fuel resource, it has the highest Btu equivalent of any fuel, and it is the least utilized.

Common sense, therefore, dictates to us that the mining of coal should be our first priority. But common sense is also whispering in my ear that coal is under-utilized for a reason; it is hard as hell to get out of the ground.

“You can strip-mine all the coal in the U.S. without hurting society any,” says Austin. We are sitting by a picture window, in those ubiquitous symmetrical motel chairs. Austin bends forward to make a point, taut and excited, the kind of person who rises to key positions as naturally as certain elements find their own levels. His features bear a chimerical resemblance to both John Connally and Jonathan Winters.

“Look, here’s how it works. This is all there is to it. You’ve got land for food productions. You swap it for energy production for five years and then turn it back to food.”

He opens his hands and shrugs. Simple.

“Society has got to decide. If we’re going to have energy we’ve got to use this resource.” He slumps back in his chair. “I don’t know. I’m beginning to not care. If people want to freeze in the dark, let ’em. You either go in for coal or for nuclear, or you go in hock up to your eyeballs to the A-rabs for the rest of your life.”

We discuss the feasibility of in situ recovery of coal, a process in which lignite is ignited underground and the gasses released are tapped for fuel. The technology for this is available—the Russians have been doing it for 30 years—and the environmental impact is, for the most part, minimal. But Austin says the efficiency is too low, although TUS is spending about a million dollars a year researching it. But Austin would rather talk about strip mining, and I can’t say that I blame him; though they will have to use in situ eventually if they want to extract the vast resources of coal in the state too deep to be stripped, for now TUS is committed to surface mining.

“I have no idea how far away we are from in situ. If you can tell me how far medical research is from a cure for cancer I’ll tell you. As a businessman, I’ll do anything that society wants to pay for. We have an environmentalist and a research center up at Fairfield. Now we don’t need one at every plant, and if we put a research center at every plant the light bill goes up in Dallas.”

I ask him if he’s encountered any opposition from people not wanting to sell the mineral rights to their land.

“Well, once I went out here and met with a bunch of people in a Negro church. A fellow came in and said he didn’t want to sell. I said ‘Fine.’ But I think he’ll sell. See, the guy next-door will want us to get all the lignite we can from his property. That means we’ll be digging right up to this other guy’s property line. So he might as well let us come onto his land too and get some benefit out of it.”

Austin is prone to slapping his palm on the arm of his chair in moments of conviction, and the gesture punctuates the conversation as it drifts into generalities on such topics as; the state of the union (“Dammit! We could build a great society if everybody would get out of the way!”), air pollution (“You know, if you inhale a whole lot of sulfur dioxide in a lab, it’s harmful. But so is taking a whole bunch of aspirin. One aspirin is helpful!”), and aesthetics (“Some of that strip-mined land in California is prettier than the land around it. Hell, you couldn’t even raise a jackrabbit on that land in a hundred years”).

“The real way to get energy to the U.S. is to get more energy. And the quickest way to get it is to strip-mine coal. And it can be done right.” He slaps the arm of the chair once more before rising to see me off. “Dammit! It can be done right!”

“You go up there to Fairfield,” he says as we shake hands, “you go up there and if you find anything wrong you call me up. That land is not being hurt.”

Fairfield. If you’ve been dabbling about for a while in strip-mining lore, the name takes on a kind of allure. Someone is always bringing it up, condemning it as an isolated showplace or praising it as a model of ecological concern. High schools go on field trips there, members of the Legislature and environmental groups and reporters are taken on tours, and they all leave with the same message: Strip Mining Is Not Necessarily All That Bad.

I have been warned that the showmanship at Fairfield is of a very sophisticated quality, but I am not really prepared to sit down in an office and listen to a TUS employee out in the corridor whistle the unmistakable strains of the old George M. Cohan standard “Harrigan.” Intentional or not, it is the subliminal high point of a firm media blitz that includes the presence of Ray Sissel, TUS’s information coordinator, who has taken the trouble to drive down from Dallas; a retrospective discussion of some of my past magazine articles led by Dick White, the plant’s manager of environmental services; and a souvenir piece of petrified wood.

Dick White’s office, where I arrive for orientation after passing through a guard booth manned by a Pinkerton operative, is located in a one-story barracks-like building in the shadow of two huge thrumming power units, each with a 400-foot smokestack through which, depending on your angle of vision, either white or brown smoke emanates.

Most of White’s wall space is given over to framed portraits of reclamation: cattle grazing picturesquely on once-defiled land, a reclaimed field sprouting with crimson clover like Tulip Time in Holland.

White sits behind his desk and reminisces how Corpus Christi Academy, my now-defunct alma mater, once slaughtered the McAllen High School basketball team on which he was playing. The transition from athlete to scientist must have been a smooth one for him to make, for he retains the neutral, industrious grace of each. His face, clean shaven and balding, looms forth, inviting trust.

He has been at the Fairfield site (more particularly at the Big Brown Steam Electric Station a few miles northeast of Fairfield) since 1971, before the plant was built and mining was begun. Before coming to work for TUS he spent eleven years as an aquatic biologist in various fishery projects.

My tour begins at the environmental research center (ERC) on the manicured shore of Lake Fairfield. We enter this building by a door that leads through a large laboratory equipped with centrifuges and microscopes and mason jars of pickled snakes. Past the lab is what appears to be a model home, with a large kitchen and a living room offering a view of the lake. A bookcase on one wall of this room is stocked with encyclopedias and field guides and bound issues of scholarly journals. The latest issue of Texas Monthly rests conspicuously on an end table.

What exactly is this place?

“The company obviously knew we were going to have some effect on the air, land, and water around here,” White explains. “This is not just lip service. They were genuinely concerned about environmental problems. And since there was a lot of speculation about effects of strip mining but very little research, we set up the environmental research center.” Voila.

White walks over to the picture window and looks through a telescope, hoping to focus on one of the bald eagles that have come to nest on the new lake. We don’t see them, but while I look through the telescope, gazing at the foreshortened perspective of bare trees against the sky, White begins to elaborate on the functions of the ERC.

“What we do here is entertain proposals by graduate students to do research on our operation and its effects on our environment. This study then serves as a master’s thesis or a doctoral dissertation.

“Because the student is awarded a fellowship by the company, people say ‘Hell, you’re paying the student to say what you want.’ But we have no review rights, no editing rights, no publication rights on his thesis. We just want to know what the answers are. This is a sincere attempt.”

He pulls five or six bound dissertations from the bookshelf and lays them on a table—studies on wildlife, soil analysis, weather, crops.

All this costs TUS about $75,000 a year. An average of nine students, selected by an interdisciplinary committee comprised of professors and scientists, work and live here in the dorm wing just off the living room.

“We don’t do anything off the top of our head,” White continues. “What we have shown here is that we shouldn’t run around without facts. I don’t like being tarred with a common brush. Just because there’s problems with strip mining in other areas doesn’t mean there’s problems here.

“I’ve been an environmentalist all my life. I believe in this. Hopefully I’m a man of enough principle where I wouldn’t have come over here unless I believed in it.”

We leave the ERC and ride in White’s car past the plant and out to the strip-mining area. The smoke from the stacks is white from this angle, so white that the whole plant could be a machine for creating the clouds that loom above it. It wouldn’t be surprising to see elves climbing about the scaffolds.

The road leads us away from Big Brown and into pastureland surrounded by groves of post oak. From the backseat Ray Sissel shows me a photo album of reclaimed land: the 8 X 10s look like the Eisenhower era photos in my old geography books: the ones with neat, easy-going pastures populated by two-tone Guernsey’s.

“I’ll be the first to grant you that we’re disturbing the environment,” White says as Sissel flips to a few pictures of the actual mining process. “But I think we’re doing a tremendous job. And it’s not all because of us. We have some real, real benign conditions. We don’t have any rocks in the overburden, we have a low sulfur content in the lignite, adequate rainfall. But the most important commitment we have is the commitment to return the land to its natural state.”

Soon White points off to the right, to a field banking slightly up from the road. This is reclaimed land. From the car it looks exactly like the untouched land off to the left, beige and bare and wintry.

White stops the car and, in fulfillment of an indiscriminate and whimsical TUS requirement, the three of us put on our hard hats before walking out into the open where the only conceivable danger to our craniums would come in the form of bird droppings.

The field we are walking over was strip-mined in 1971 and reclaimed about a year later. Today it is an expanse of coastal Bermuda and incipient crimson clover, with small embryonic copses of cottonwood, sycamore, and ash seedlings. Retention ponds, to catch toxic runoffs from the soil and to prevent erosion, are tucked into small gullies that crisscross the pasture.

There is nothing very wrong with this land, I suppose. There are peculiar, almost unnoticeable rills, like the tracks left on a lawn by a new underground sprinkler system, and there is a spooky silhouette of a dragline taking up a good deal of the horizon, but this is nit-picking.

Still there is nothing all that right about this land either. Remember on The Twilight Zone when astronauts would crash-land on some planet, and the inhabitants, wanting their new captives content while they performed their nefarious experiments, would build them a replica of earth? This place is like that for me: it has the feel of earnest but naïve artifice.

Understandably, a company like TUS cannot accommodate itself to individual neurotic tremors. Well, yes, for what they have set out to accomplish they have done a good job. Here, anyway. Here in a natural savannah where the lay of the land can be easily simulated after it has been disturbed, here where TUS itself owns most of the land and not some farmer who needed the money more than the topography of his birthplace. TUS has the technology, the environmental data, and the legal obligation to “redo” a heavily wooded place like Tatum, to perform a root canal on the great molar of East Texas, and then set into motion the arduous, ongoing, eternal process of reforestation. But will it take? That dragline on the horizon is capable of extracting 70 cubic yards of earth in one scoop. Does the hand that built that have a green thumb?

Returning to the car, we drive on to an area that has not been seeded yet, but which is in the process of being filled in and smoothed down by bulldozers and dump trucks and odd anthropodal machines I can’t identify. The land is dark gray, bare as the moon, but it lacks the cutting edge of real aridity. It looks like the first layer of an electric train layout that some giant model railroader in an engineer’s hat has just finished applying. On its rim, the overburden is piled up in a “herringbone” pattern that suggests a miniature Tibetan mountain range.

“This is what people think the land is going to look like,” White points out.

Down, down, down we descend, 90 feet into the maw of the strip mine. Overburden, stratified, rises above us. The car moves ahead on a highway of lignite. Further on we can see the great bucket, suspended on the long boom of the dragline, dip into the earth.

Here is the way it works: the land is mined in long parallel bands, so that as one trench is dug the overburden is shoveled into the empty, played-out trench next to it. This is what the dragline ahead of us is doing now, forming neat telescopic peaks off to the side with its overburden. Close-up the machine is massive, and it seems that for a considerably long time as we approach it we are under the shadow of the 285-foot boom that swings back and forth above us with anomalistic spryness. White waves to the face of the machine and from a glass cab on the right front side that looks like the eye of a grasshopper, a man waves us on board.

Inside the cab I watch the operator work the levers; through the picture window the boom and the bucket swing so far ahead, so autonomously, that it does not seem possible they have anything to do with these two simple levers. The operator’s job seems merely a formality; in a machine this massive, cause and effect can only be inferred. The dragline sways back and forth, following the lateral sweeps of the boom, and this movement and the glassed-in vista ahead of us make me think of those early Cinerama movies in which Lowell Thomas took you on a tour of the Seven Wonders of the World.

After a few minutes of this, White takes me back into the dragline’s internal organs. We come to an area the size of a large two-story house filled with electric motors and generators and transformers and winches of thick self-lubricating cable. The floor shifts beneath us like a fun house.

Before we drive away we watch the dragline walk. It does this like a robot, lowering two huge pods onto the ground and using them for leverage to scrunch itself back on its haunches. The operator stands on the catwalk outside the cab: this is one trick the machine can do on its own.

A buzzard sways above the trench. I don’t know what it could be looking for.

At another site we watch a smaller version of the dragline scoop up coal and pour it into gargantuan black trucks which will take it down the road to a pit near the generating station. There the lignite will be crushed and then either stored or sent on to the pulverizers and furnaces where it will become, finally, fuel.

White and I ride the elevator up to the twenty-second floor of one of the generator units. The shrill throbbing sound in the plant is deafening, and so we speak as little as possible and look out at the landscape, at the fields of untouched and reclaimed land, at the great ugliness of the active trenches, at the mountain of stored coal, and at the moon vehicles traveling, swarming over everything.

Is it bad? I don’t know. I know that that bland, contoured, rectified land out there speaks as certainly for our time as those unrepentant mounds back in Darco speak for theirs. We now have the means, not only to scrape off the entire crust of the earth, but also to put it back. The earth is a letter we can finally steam open and close up again.

When I glance at my shadow, I see the unfamiliar shape of a hard hat resting on my head. Maybe it looks like a conquistador’s helmet only because at the moment I’m thinking of that mythical white man, Bad Thing, who came to this country long ago to demonstrate how he could both wound and heal, who with his great knife could gouge and extract and ignite and restore to no purpose the Indians could perceive, except maybe to frighten them, and to prepare the way for his children.