“TEXAS A&M IS NOT GOING TO BECOME a school of nerds.” These unlikely words have just been spoken by Ray Bowen, the president of the university, who is explaining to me why he doesn’t want to see the average Scholastic Assessment Test score of A&M students rise much higher than the current 1174—even though scores at the University of Texas are higher. “A&M’s mission has always been to train leaders,” Bowen says. “I don’t ever want us to get to the point where test scores count more than leadership.” That the president of Texas A&M should be worried about keeping test scores down instead of getting them up is all the evidence necessary to establish how much A&M has changed in recent years and how far it has come academically. As recently as the mid-seventies, the catalog requirements for admission to the College Station campus were only that a student had to be a college-track high school graduate of good moral character and free of infectious and contagious diseases. Today A&M’s SAT scores exceed the average at most major state universities—not just gimmes like Louisiana State University and Oklahoma but also such respected flagship institutions as Ohio State, Illinois, Indiana, Purdue, Minnesota, Connecticut, and Washington.

Reputations, though, are hard to live down, and for many Texans who have grown up on Aggie jokes, the idea that the onetime Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas has evolved into an academic powerhouse is a Copernican challenge to long-held assumptions about the order of the universe. Indeed, as Bowen switches into a conversation about his desire to bring A&M’s library up to the elite standards of the Association of Research Libraries, a corner of my mind dredges up the hoariest of Aggie jokes: “Did you hear what happened to the Aggie library? It had to close because somebody checked out the book.” And the sequel: “When the book was returned, the library couldn’t reopen. All the pictures had been colored.”

But the old Texas A&M that gave rise to the stereotype no longer exists. Last October U.S. News and World Report’s annual ranking of American colleges and universities—based on eleven numerical indicators ranging from test scores to the percentage of alumni who give money—placed Texas A&M among the top fifty schools in the country for the first time. UT-Austin, which had been on the list in previous years, dropped off. And that’s not all. A&M now has the largest full-time undergraduate enrollment in America. Its annual research funding ranks sixth nationally. Among Texas colleges, it has the best retention rate from freshman to sophomore year and the best graduation rate. At a time when state and federal support for education is under intense budget pressure, A&M has just raised $637 million from alumni and other private sources—the largest fund drive ever completed by a public university. The University of Texas is still the superior graduate institution, but Texas A&M had earned the right to be called the best public undergraduate university in the state.

Any attempt to rate something as individualized and subjective as higher education is open to attack, of course. UT student body president Jeff Tsai denounced the U.S. News ranking system as “a specious attempt to quantify the intangible elements of higher education” and called for the university to withhold statistical data from the magazine in future years. Still, the U.S. News top ten—Yale, Princeton, Harvard, Duke, MIT, Stanford, Dartmouth, Brown, Cal Tech, and Northwestern—could hardly be confused with the Associated Press football rankings, nor does it suggest that there is some giant flaw in the formula. And if it is intangibles that make the difference in education, well, Texas A&M will match its intangibles with anyone’s. For almost a century, intangibles—tradition, loyalty, school spirit, service to the school—were all that Texas A&M had going for it. These values, sometimes referred to by Aggies as “the other education,” remain among A&M’s most cherished assets. UT president Robert Berdahl has told Ray Bowen that what UT needs is a stronger sense of place and more loyalty from its alumni. When the University of Texas wants to emulate anything about Texas A&M, you know that times have changed.

The rise of A&M to academic prominence is a remarkable odyssey. It was born a stepchild in 1876, declared by the state constitution to be a “branch of the University of Texas,” which would not even exist for another six years. For the first half-century, the school faced repeated threats by the Legislature to shut it down. As recently as the 1950’s it was more likely that the school would cease to exist than become a serious academic institution. Over the years, A&M has had to overcome politics, poverty, isolation, fire, and ridicule. Most of all, though, it has had to overcome Aggies.

The lifetime love and loyalty that Aggies have for their school have been A&M’s greatest asset—and its greatest liability. Its long history as an all-male, compulsory military institution made the experience of attending A&M intense and unique. All universities must deal with alumni who don’t want their school to change, but at A&M the pressure from former students (which is the correct designation for Aggie alums, since there is no such creature as an ex-Aggie) to resist change has been extreme and unyielding. No university has had to endure more fights over what its fundamental mission should be. Until recent years, the occasional attempts to elevate scholarship inevitably lost out to advocates of technical education, military training, and character and leadership development.

The history of Texas A&M, then, has been an unending battle between New Aggies, who saw the change as something that could elevate the school, and Old Aggies, who were passionate in their conviction that change would destroy it. To describe such feelings as hypersensitive is an understatement. John Lindsey, a current A&M regent from Houston, says that there are Old Aggies who still have not spoken to him since he advocated the admission of women back in the sixties. Even as the school gained academic stature through the seventies and eighties, the university administration remained mired in an Old Aggie mentality, managing the campus more like a family business than a modern billion-dollar enterprise. Record keeping was minimal, lines of authority were bypassed, and controls on research were ignored. The result was a series of soap operas and scandals that obscured from the public just how good a school Texas A&M was becoming: the hiring and then the firing of football coach Jackie Sherrill, in both cases after open power struggles at the highest levels of the university; an embarrassing claim that A&M scientists had achieved a breakthrough in cold fusion research; an even more embarrassing claim that an A&M chemistry professor had found a cheap way to turn base metals into gold; accusations of harassment made by female members of the corps of cadets against their male colleagues; and most recently, a long-running investigation by the Texas Rangers into management practices at the university that led to controversial convictions on ethics charges of Ross Margraves, the chairman of the board of regents, and Robert Smith, the school’s most powerful administrator. The success of Texas A&M today is all the more impressive in the light of what the school had to overcome to achieve it.

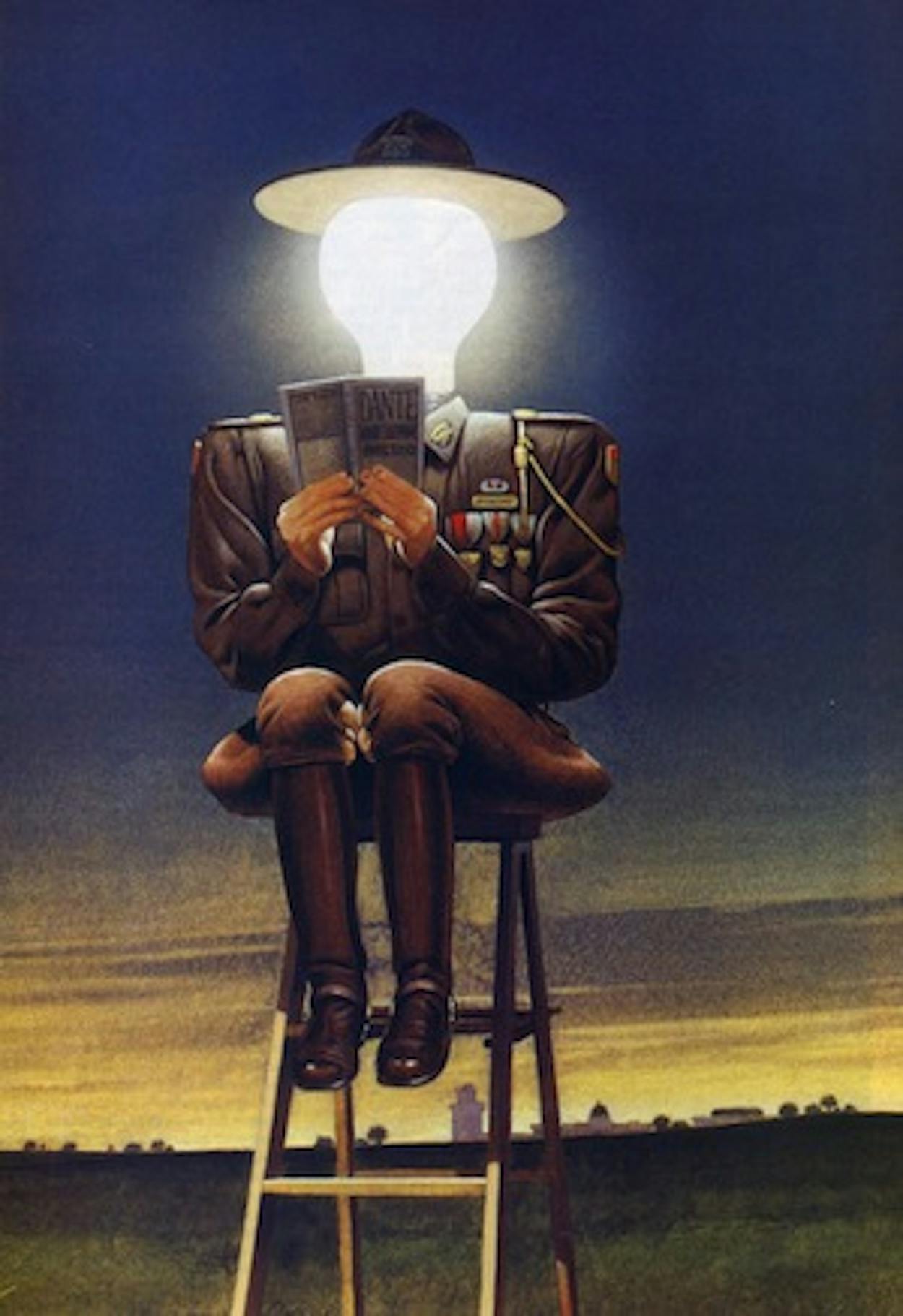

“Inspiration to Greatness”

Outsiders have always had a hard time understanding Aggies, and I confess to faring no better. As an undergraduate at Rice University, I would occasionally go to College Station to watch athletic events, and I always had the uncomfortable feeling of entering a Third World country. The yells, the gestures, the conversation, even the fierce and close-cropped look of the students (all men in those days) were the rituals of a primitive tribe. With its graceless cell block buildings, A&M resembled a prison more than a university. How could anyone revere such a place? Aggies, I thought, were people who believed everyone was out of step but themselves. This view crumbled when I entered the post-collegiate world and met A&M graduates I came to like and admire (and, in one case, work for). I had to admit that, whatever I thought about the behavior of people who went to school there, the condition didn’t seem to be permanent. While I still root for the University of Texas, where I received a law degree, to beat the Aggies in athletics, I realize that the old distinction between the two schools—sophisticates versus hicks, or from the A&M perspective, tough guys against teasips—is long out of date. In the more important arenas of politics and education, there is no rivalry between the two schools. They are on the same team, aligned against envious smaller schools and local legislators who want to grab more state funds for their hometown colleges. UT and A&M are Texas’ best hope to prevent a brain drain—a specter that used to haunt Texas but no longer does, thanks largely to the quality of education at the two schools.

So I returned to Texas A&M this year with a different viewpoint, and I saw it through different eyes. The campus is still far from handsome, but it has an unmistakable energy. A&M’s explosive growth—from 10,000 students to 43,000 in the past thirty years—has been accompanied by a building boom, mostly of undistinguished high rises that appear to have been wedged into any available vacant space, sometimes at odd angles. Students walk faster than they used to, having more distance to cover (the busy railroad line that used to be the school’s western boundary is now in the middle of the campus), and they don’t say howdy when they pass each other either, as they did in the old days. Instead of “whipping out”—offering handshakes to visitors—they just smile. Only a handful of students are in uniform; the corps of cadets is down to 2,200 members. The remainder dress casually, jeans and T-shirts on a cool day, shorts and T-shirts on a warm one, the main contrast to their peers at UT being that more shirttails are likely to be tucked in at A&M. At first glance the scene might pass for an Old Aggie’s worst nightmare. Everything has changed.

And yet, what is remarkable about Texas A&M is how much has remained the same. The sense of place is exuberant. The shuttle buses (white with maroon trim) that run through campus identify their routes not by numbers or letters but by Aggie terms: Old Army, Gig ‘Em, Hullabaloo, Bonfire, and so on. The streets are named after Aggie icons: former governors, former school presidents, former athletic heroes. The buildings may be ugly, but Texas A&M has the world’s most beautiful campus from the ankles down. The grounds are Disney World clean, and Aggies who come across a stray piece of trash invariably pick it up and throw it away. Application forms for Aggie license plates are prominently placed at the checkout window of campus parking garages. Plaques in the Memorial Student Center tell the story of Aggies who earned the Congressional Medal of Honor. In another part of the center short multimedia presentations—a series of still photographs with voice-overs—provide an introduction to Aggieland. Ostensibly the presentations are for visitors, but the earnest freshman who is manning the information desk nearby tells me, “Students looking for a pick-me-up drop in to watch.” The one that was running at the time was called “Inspiration to Greatness.” On the screen, a professor, accompanied by swelling symphonic music, was saying, “We will reach into the future as a global university.” Another said, “A&M has become a great university in the last ten years and it will become a greater university.” More faces marched across the screen: “The tradition of greatness moves us forward… . Texas A&M means being part of something larger than ourselves… . That’s why Texas A&M is great. That’s what it takes to be an Aggie.”

Highway 6 Runs Both Ways

More than a century of struggle over what it takes to be an Aggie would pass, however, before a comfortable equilibrium was reached. Texas A&M was barely three years old when the school faced its first identity crisis. It had opened in 1876 as a land-grant college, which meant that it received funds from the sale of federal lands in exchange for teaching agriculture and mechanical arts. The idea was to educate the industrial class and leave classical studies for private colleges, which tended to serve the wealthy. But there were few textbooks and fewer trained instructors in the disciplines that A&M had been created to teach, and almost immediately it began to emphasize classical education. This was the path down which most land-grant colleges would go—but not Texas A&M. By 1878 the Texas State Grange, a politically potent farmer’s organization, was complaining about the lack of emphasis on agriculture, and the next year Governor Oran Roberts pitched in: A&M’s mission, he said, was to teach students “How to produce two ears of wheat and corn and two bales of cotton by the same labor and capital that have been heretofore producing but one.” Students interested in literature and science, he noted, “are seldom found to spend their lives between the plow handles or in the workshops.” Late that year the board of directors, as A&M regents used to be called, fired the first president—who had been recommended by Jefferson Davis after the former president of the confederacy turned down the job—and the entire faculty of nine. The new president declared, not surprisingly, that students had to major in one of the two land-grant areas of study.

Two years later Governor Roberts called for the building of “a University of the first class”—The University of Texas. A&M would remain the Agricultural and Mechanical College. UT, in the discourse of the day, was “The University,” which Aggies derisively shortened to T.U.—a designation that survives in College Station to this day. For more than forty years, A&M would fight its nemesis for a share of the income from the public lands that the state constitution had set aside for UT, of which A&M was legally a branch.

All of this may seem like ancient history, but at Texas A&M, all history is contemporary. At a school that places such a heavy emphasis on tradition, nothing about the effort to become a modern university was harder than resolving the issue that had dominated its past. Was A&M a university or a vocational school? Was it a second-class adjunct of the University of Texas or an equal? Who should be allowed to go to school there? Was military training of primary or secondary importance? Could the good features of “the other education” survive an emphasis on formal education? Every one of these battles goes back at least a hundred years.

The new agricultural curriculum was not a success. As A&M professor Henry Dethloff observed in his history of the school’s first one hundred years, the farmers’ sons who went to college did so in the hope of escaping the farm, not going back to it. During the 1880’s there was serious talk, in the Legislature and in the press, of closing A&M down and converting it into—this is too perfect—a lunatic asylum. The UT regents proposed that they take over A&M. What saved A&M was the decision to offer the presidency to Governor Lawrence Sullivan Ross. A former Texas Ranger who had killed the Comanche chief Peta Nocona in battle and “rescued” his white wife, Cynthia Ann Parker, Sul Ross made peace with UT and pried money from the Legislature, and talk of shutting down the school subsided. But his lasting importance at Texas A&M was his declaration that military training at the school should be of “transcendental importance.”

A&M had found its calling. Education, even agricultural education, was relegated to secondary status: As Dethloff put it in his history of A&M, ” ‘college spirit’ and indoctrination surpassed and even began to smother academic interests.” Cadets lived together, drilled together, went to class together, even danced together. (At campus-sponsored stag dances, “girls” were identified by a handkerchief tied around a cadet’s arm.) The Corps was an all-inclusive fraternity. Its rituals became traditions; its traditions became sacrosanct. Compulsory membership in the Corps, opposed by much of the faculty, ceased to be an issue after 1912, when the regents notified administrators, faculty, and staff that “if there is among them those who cannot conscientiously support the military feature they are advised that they will seriously hamper the institution by continued opposition.” This get-in-or-get-out attitude would become an Aggie hallmark. As the saying goes, “Highway 6 runs both ways.”

By the teens the consequences of A&M’s military bent were all too clear. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching visited the campus and reported, “It is a display of great leniency to term the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas an institution of higher education at all.” There were renewed efforts to close the school. Following fires that destroyed the mess hall and the main building, the Legislature in 1913 was reluctant to appropriate money for new construction. Only a personal guarantee by regents’ chairman Edward Cushing enabled A&M to borrow money and avoid being consolidated with UT.

The discovery of oil on UT’s public lands in 1923 brought the issue of A&M’s relationship to UT to a head. The issue of whether A&M, as a branch of the university, was entitled to a portion of the oil revenue became worth fighting for. After A&M threatened to go to court, the two boards of regents agreed on a compromise: UT would get two-thirds, the Aggies one third, a division that inspired another Aggie joke. “Why was A&M’s share just one third? The Aggies got first choice.” There is a grain of truth here. A&M, starting from zero and having an uncertain legal position and less political influence than UT, was willing to settle for a minority interest.

With its funding assured, A&M no longer faced the threat of closure. But the oil windfall was spent on bricks, not brains; new buildings popped up on campus, with no effect on the quality of education. A school of arts and sciences was formed in 1924, but it offered just two courses—one called liberal arts and one called sciences. The chemical engineering department failed to achieve accreditation in 1937. Faculty members were not required to do research and had no tenure system. As late as 1946, only 17 percent of them had Ph.D.’s. Post-war A&M, historian Dethloff says, was still a school for the training of agriculturists and engineers and little else.

No one at A&M seemed terribly troubled by this state of affairs until the fifties. That’s when A&M’s enrollment began to decline during a decade when attendance at public colleges across the state was growing by 92 percent. Twenty thousand Aggies had fought in World War II, seven thousand of them officers commissioned at the college. But with the war over, the appeal of military training to returning vets and younger students alike was diminished. To the faculty, the remedy was obvious: End compulsory membership in the Corps (the freshman attrition rate in Corps dorms hit 48 percent in the fall of 1946) and admit women. But the regents, the alumni, and the Corps were Old Aggies who resolutely opposed any change: If Aggies weren’t going to be in uniform, if they weren’t going to say howdy and whip out, then they wouldn’t be true Aggies anymore, and Texas A&M wouldn’t be Texas A&M. The school president made the Corps optional in 1954, but after four years of open hostility between military and civilian students, the board reversed the policy. Once again, the survival of Texas A&M was at stake.

None Udder But Rudder

Into this volatile and deteriorating situation stepped the right man at the right time, although no one either intended or foresaw what would happen. In 1959 James Earl Rudder became president of Texas A&M. He was Old Aggie to the core—class of ‘32, an industrial education major, an ex-football coach, a general, and a World War II hero. Years later, a number of Rudder’s contemporaries would try to take credit for persuading him to open A&M’s doors to women and end mandatory Corps membership once and for all, but the reality is that it did not take a great amount of insight to see what had to be done. What it took was courage and clout—the willingness and the stature to stand up to the Old Aggies—and Earl Rudder had plenty of both. During World War II he had scaled a cliff on D-day, leading a team of Rangers that captured a key German position above Omaha Beach. In 1954 Governor Allan Shivers had called Rudder away from his Brady ranch to take over the scandal-ridden General Land Office, and he had restored the integrity of the agency. When Rudder ran for reelection, he wanted a slogan that people could remember. Current A&M regent John Lindsey was his Harris County campaign manager, and all he could think of was “None udder but Rudder.” The general hated it, but it became the successful campaign’s unofficial mantra.

Rudder had no academic background before he came to A&M as vice president in 1958, but he could see that the school was in serious trouble. The campus was in turmoil over the issues of coeducation and compulsory military training. The student senate had called for the resignation of the editor of the Battalion after the student newspaper came out in favor of admitting women. Academics were in sad shape, the library was terrible (“seriously inadequate” was the verdict of professional librarians from other colleges who had evaluated it in 1949), and the faculty and the administration were full of deadwood. It wasn’t long after Rudder became president that he began telling friends, “What A&M needs is a lot of funerals.”

Earl Rudder had to become a New Aggie to save Texas A&M from fading into oblivion, but it was not a role that came naturally to him. When it came to facial hair, student protests, and highfalutin ideas, he was Old Aggie all the way. A&M had no art history course and Rudder didn’t see the need for one. To him, art meant only one thing—pictures of naked women. Rudder got so exasperated with Wayne Stark, the longtime and much-loved director of the student center, for trying to interest Aggies in art that he would grumble to friends that he ought to fire Stark, which of course was as unthinkable as the regents firing Rudder. Stark had established a tradition called Cultural Weekend, in which he would take students he regarded as the cream of the crop to Houston, where they would stay at the Shamrock, four to a room, and go to the art museum and the Alley Theatre. Rudder, who hated the whole idea, made Stark change the name of the outing to Leadership Weekend.

Rudder knew that it would be easier to admit women than to end compulsory Corps membership. There was considerable precedent for coeducation. The daughter of a professor attended classes in 1893. That same decade, President Ross wanted the Legislature to establish a girls’ industrial school at A&M, but the proposal died in the Legislature. Limited coeducation for families of faculty and students’ wives was allowed into the mid-teens (and then ended), in the early twenties (and then ended), and in the thirties (and then ended). After World War II, though, coeducation became a much more emotionally charged issue, the litmus test of whether A&M would have to give in to a changing world.

Rudder had two strategically placed allies who favored the admission of women. One was the chairman of the board of regents, Sterling Evans; the other, the formidable state senator from Brazos County, Bill Moore. In 1953 Moore had passed a nonbinding resolution in favor of coeducation at A&M through the Senate while no one was paying much attention. When one senator asked Moore what the resolution said, Moore, who was in the process of earning the nickname the Bull of the Brazos, growled, “Read it yourself. You never vote with me anyway.” The resolution passed, but when Moore’s colleagues found out what he had done, they rescinded the vote two days later by a vote of 28-1. Never one to be graceful in defeat, Moore barked that A&M would be coeducational within ten years. He was right on the money. Moore held up the appointment of regents who opposed coeducation, and saw to it that Governor John Connally got the word that future appointees would not be approved unless they were willing to let women attend A&M. Suddenly the A&M board found itself with a 5-4 majority for admitting women. On April 27, 1963, in what was reported to be a unanimous decision, the regents reinstituted the old policy of letting the wives and daughters of people at A&M attend school as well as women who wanted programs available only at Texas A&M. Two years later Rudder was allowed to admit women at his discretion.

In 1965 the board voted to end compulsory membership in the corps of cadets. Rudder blamed a decision by the Department of Defense to cut back on college ROTC programs, but that was just a rationale for what had to be done. Although the Old Aggies didn’t like it, they couldn’t take on Rudder. Only he could have changed A&M from an all-male, all-military school. But Rudder had too much Old Aggie in him to be an ongoing reformer. A&M was slow to install restroom facilities for women and didn’t build a woman’s dormitory until 1972, two years after Rudder’s presidency ended with his death. Even so, he remains the school’s greatest president, the one who set A&M free. (“If it hadn’t been for Earl Rudder,” says state agriculture commissioner Rick Perry, a yell leader during the Rudder era, “Texas A&M would be The Citadel of Texas today.”) Rudder is one of two A&M presidents honored by a statue on campus. The other is Lawrence Sullivan Ross, whose work in shaping Texas A&M Rudder dismantled.

The Logic Demon

It isn’t hard to improve a university. All that’s really needed is the money, the will, and a compatible institutional culture. In the space of a few years, Texas A&M went from none of the above to all three. The subsequent history of A&M has been the steady ascendancy of New Aggies over Old Aggies.

In the seventies A&M suddenly found itself in a fortuitous position. With the Corps no longer at the center of life, A&M students could put education first. With the admission of women, the talent pool available to the school doubled. Oil royalties from university lands were flowing in. A&M was practically a brand-new university, except that it had the benefit (and sometimes the downside) of a hundred years of tradition and a fanatically loyal alumni.

A&M’s timing was perfect. The nation’s elite universities had gone through their growth spurts in the sixties, when A&M was stagnating. Graduate schools were producing many more Ph.D.’s in the seventies than they had in the sixties—but the top universities had already stocked their faculties in the previous decades. A&M (and the University of Texas) had jobs available, oil revenue that could supplement state funding, and the luxury of recruiting in the buyer’s market. (“We turned down people from Stanford!” a longtime A&M administrator told me.) The academic reputation that both schools enjoy today is largely as a result of the faculty recruiting that was done fifteen and twenty years ago.

To get a closer look at how A&M had made use of its opportunities, I decided to visit the college of liberal arts, the area that has been A&M’s biggest educational shortcoming over the years. Liberal arts received a big boost in 1986, when the New Aggies on the faculty senate adopted, over objections from Old Aggies, core requirements that required all students, even those in agriculture and engineering, to take a number of courses in liberal arts. Another nineteenth-century decision had been reversed; A&M’s mission would incorporate classical education for all students after all. Today liberal arts is the third largest of A&M’s ten colleges, trailing only engineering and agriculture in the number of students who major in one of its subjects. A film touting liberal arts has just been added to the student center’s collection of Aggieana. (“A broad-based education gives us the edge we need to be leaders in the twenty-first century.”)

The department that intrigued me the most was philosophy, because the concept of an Aggie philosopher seemed to be something of an oxymoron. A&M’s emphasis on leadership, service, and other practical skills that make up “the other education” are not exactly conducive to a life of cogito ergo suming. But philosophy at A&M turns out to be very practical indeed, a case study in New Aggieness.

“Did you know that philosophy majors do the best on the law school entrance exam?” asked Robin Smith, who came to A&M from Kansas State to head the philosophy and humanities department three years ago. He spoke with a serious air that was enhanced by a gray beard that ran from sideburn to sideburn and encroached onto his cheeks. “At the undergraduate level, most philosophy departments in the country are dominated by students who want to go to law school. We want to learn how to examine arguments. We have to learn to listen to the arguments of others. You can’t reject their opinions unless you understand why they think they are right.”

I asked Smith about what I had heard repeatedly from administrators and faculty at A&M, starting with President Bowen: One reason A&M has come so far so fast is that the university is constantly reevaluating itself. This year, the university is going through a formal planning process in which every department and every college is being asked to propose ideas for self-improvement. All universities do this, of course; the question is, Does all the planning mean anything?

Smith pondered. “How can I put this?” he said. “A&M has its bureaucratic complexities, but there is considerable institutional support for innovative thinking and new ideas.” He gestured to a stack of examinations on his desk. “I teach introductory logic to one hundred and sixty students,” he said. “I can’t give everybody half an hour a week of individual attention. So I thought, ‘Maybe participation could be virtual.’ Two professors got a grant from the university for a Web site where students can get help and do practice problems. They wrote a special program for it. It’s called the Logic Demon.

“Right now, we’re giving ourselves a long, hard look. We have one of the three or four best master’s degree programs in the country. Do we want to expand to a Ph.D. program? There are plenty of Ph.D.’s in the field now. Maybe we should have postdoctoral fellowships or something else instead that are designed for people in executive, administrative, and political positions.

“We have to ask ourselves, What should this department be like in ten years? What will this discipline be like in the future? Are there applications for philosophy? The university is especially open to ideas that have some usefulness to other disciplines. Take consciousness. How do I know that you’re conscious? As philosophers, we spend a lot of time worrying about things that are far from everyday life. But there are a lot of people in other disciplines who are trying to understand intelligence. Are computers intelligent? Are animals? If philosophers can give them a clear picture of the issues in determining what intelligence is, we can help them with their work.”

And so I discovered that philosophy and Texas A&M are not incompatible after all. A&M is not likely to establish a broad Ph.D. program in philosophy, but there is room for niche programs that are practical. Hegel himself couldn’t have devised it better; thesis plus antithesis yields synthesis; philosophy plus practical education yields practical philosophy.

Darn Good Aggies

The Old Aggies turned out to be totally wrong. Admitting women and ending compulsory military training did not ruin Texas A&M. Students may not say howdy, but other basic values that mattered a lot more—like the sense of family—have not changed.

Brooke Leslie, who in 1994 became the first woman student body president at Texas A&M, found out about the sense of family before she ever enrolled. She is the model of a New Aggie—smart, serious, self-confident, female (this year, for the first time, the freshman class has more women than men), and every bit as loyal to Texas A&M as any Old Aggie ever was. She is from the small North Texas town of Glen Rose, and she came to A&M not for emotional reasons but because she had been recruited by Joe Townsend, the associate dean of agriculture, who had heard her speak at Future Farmers of America meetings. She had been awarded a full scholarship to study agriculture.

One day in the summer of 1990, before the start of her freshman year, Brooke received a call from Townsend. Would she come to College Station to talk with him? When she arrived, he said he wanted to help her get adjusted to A&M since she was coming from a small high school. What sort of activities might she be interested in? After she mentioned student government he said, “Brooke, you have a chance to make history. It’s going to be hard work, but you can be the first woman president of the student body at A&M.”

I first saw Brooke Leslie in one of the multimedia presentations at the student center. The theme of this one was leadership. It began with the voices of Churchill, Martin Luther King, and others, and then showed a tall, dark-haired woman student welcoming George and Barbara Bush at the groundbreaking for the Bush presidential library at A&M. “You two would have made darn good Aggies,” she said. Who is that? I asked the man from the university relations office who had brought me over to watch the films. “That’s Brooke Leslie,” he said. “She’s going to be the first woman president of the United States.”

Today she is a second-year law student at the University of Texas with 3.7 grade point average. I caught up with her at a sandwich shop near the law school after class and before her job at a downtown law firm. She was wearing a long black skirt and a red jacket with a black collar. Her hair was pulled back but not tightly, and she kept brushing stray wisps behind her left ear.

“From the very beginning,” she said, “it was drilled into us that you go to A&M to get an education, but you leave to make a difference. You learn that you’re part of something bigger than yourself, and that you’re part of a huge family, that you have to give back to the university. I know it sounds like I’m reading from the A&M recruiting brochure.”

That the tradition of “The other education” has thrived in the New Aggie era is no accident. A deliberate effort to preserve and promote it is made by administrators like Joe Townsend and by students. Columns in the Battalion emphasize tradition (TRADITIONS MORE IMPORTANT THAN INDIVIDUALS INVOLVED read one headline) and service (“Part of every student’s responsibility as an Aggie is to attempt to improve Texas A&M.”) At many state universities, fraternity and sorority members owe their primary loyalty to their social organizations, but at A&M, they wear T-shirts that say “Texas A&M Greeks—Aggies First.” Two thirds of the freshmen attend a four-day summer orientation program called Fish Camp that is held at a Methodist Church retreat in East Texas, a four-hour ride on non-air-conditioned buses from the A&M campus. Students learn the arcane yells, encounter traditions called Muster and Silver Taps that honor the Aggie dead, and meet with two counselors in groups of twelve known as DGs (discussion groups). They talk about everything from how to study to where to go on a Saturday night. Fish Camp is entirely student run, and counselors have to pay $85 to attend just as students do.

Among the traditions at A&M is Open House at the student center, a fall weekend when 15,000 students come to check out some seven hundred organizations on campus. That level of participation, says President Bowen, is “big-time unusual.” To encourage leadership, the Association of Former Students donates money to the vice president of student affairs for funding the service ideas of students. Several years ago, a group of black students got some money to hold a conference for three hundred black student leaders in the Southwest. Now an annual event, the conference draws a thousand students to A&M today. One of Brooke Leslie’s goals as student body president was to establish scholarships for service and leadership, regardless of grades. “That’s so important here, I felt it should be recognized,” she says. Now there are ten endowed service scholarships.

New Aggies have a different feeling about the school than Old Aggies do. “It’s not better or worse,” Brooke says, “It’s just different. I think it used to be based on mainly male camaraderie. For me, it’s the hometown values, it’s people who haven’t lost sight of what it means to be good friends, it’s the opportunity to develop my skills in an atmosphere conducive to community service.

“It took me a year to fall in love with the school. As a freshman, I enjoyed A&M, but I wasn’t in love with it. Then came Muster, on San Jacinto Day. I hadn’t really planned to go, but I happened to be walking past the coliseum just at the right time. I followed the other students in. The Ross Volunteers fired a 21-gun salute, and family members lit candles for Aggies who had passed on in the last year. When each name was read out, friends and family around the building called out ‘here.’ I thought to myself, ‘I am so lucky to have gone here. It’s so much more than a degree.’”

Never Been Better

An adoring history of Texas A&M published in 1951 observes, “It has been a typical growing youngster in many ways, except that in its tendency toward extremism it has been more glaringly good and bad than most. And now it has begun to mature … as we view the college today, it has achieved a substantial degree of dignity and has lost little of its driving ambition and fire.” With the advantage of hindsight, we know now that just when a new A&M seemed to be emerging, the Old Aggies would soon lead it close to ruin. That is a useful lesson for New Aggies to remember today.

Texas A&M has never been a better university. A hefty 49 percent of its students were in the top 10 percent of their high school graduating classes—higher than UT, higher than Wisconsin, higher than all but a few elite state universities. Just 33 percent of students who apply to medical schools are accepted; at Texas A&M, the figure is 44 percent. A recent study by the State University of New York at Stony Brook determined that the political science department whose faculty had the most articles accepted for publication in the three leading professional journals was Texas A&M. In defiance of the laws of probability, A&M has managed to keep everything that is essential to the Aggie tradition of “the other education” while shedding, albeit with great difficulty, almost everything that was nonessential or harmful. It has quadrupled in size without losing the feel of a much smaller school.

And yet there is always a danger at A&M, always a concern that the Old Aggies may resurrect themselves and undo what has been done. Aggies are loyal, but they are not always loyal to the same idea of what Texas A&M is. Just as Old Aggies once thought that A&M would never be the same if women were admitted, the Old Aggies of the future may think that A&M will never be the same if academics become more important than some other tradition, such as conservative political values or success in football. Highway 6 still runs both ways.

I suppose that attitude is why I have a hard time imagining myself ever going to school there. At A&M, the culture, the traditions, the sense of family, the values, are all handed to you, and you are expected to accept them. It’s a nurturing environment, but that is not the right environment for me. Come to think of it, though, Texas A&M seems like the perfect place for my son.

- More About:

- Aggies

- College Station