This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

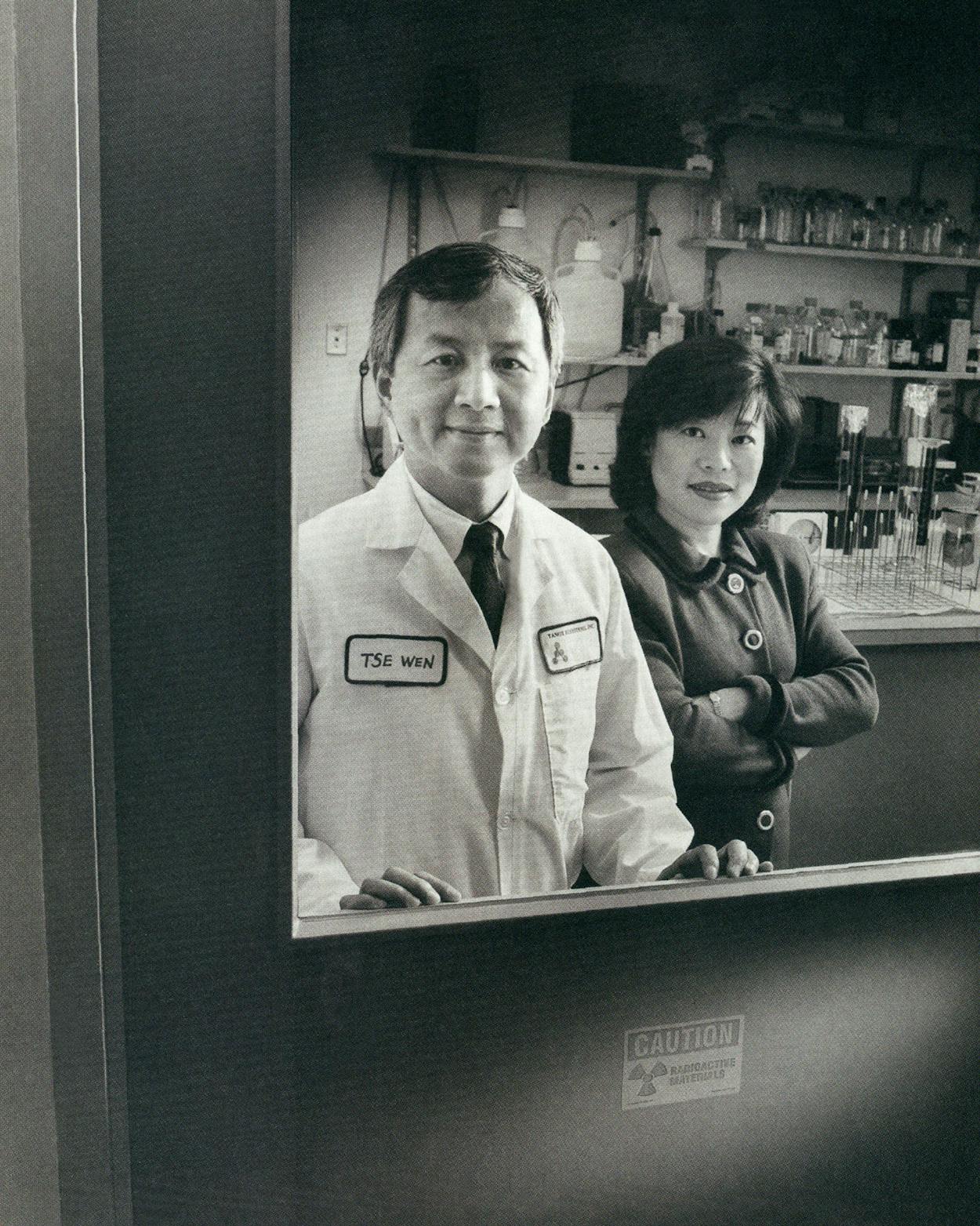

At first blush, Nancy Chang seems an unlikely person to wage war with an industry giant over a billion-dollar remedy for allergies and asthma. She is small and shy and can be humble. When you scratch the surface of her personality, however, you find a woman of singular ambition. At 45, Nancy is the president of Tanox Biosystems in Houston. Her former husband, Tse Wen Chang, 47, is the creative genius behind the company and serves as its vice president of research and development. It was his idea to use the tools of DNA technology to develop an antibody that could stop an allergic reaction or asthma attack before it ever gets under way. Tse Wen’s invention could bring relief to millions of Americans—among them thousands of Texans who suffer in undignified sniffling misery every spring, fall, and cedar season. But now the Changs are feuding with a formidable rival that wants to produce essentially the same product, and whether they will ultimately receive any credit or any gain for their idea has abruptly been called into question.

Nancy and Tse Wen Chang emigrated from Taiwan 22 years ago. In a high-tech version of the classic American arrival story, they obtained Ph.D.’s from Harvard Medical School and then worked on pioneering projects in the young field of biotechnology before they were recruited by the Baylor College of Medicine to come to Texas. After settling in Houston in 1986, they sank their personal savings and most of their waking hours into Tanox, the privately held company they founded together. Tanox has several products in development, including a novel AIDS therapy, but by far the most promising of its undertakings is the remedy for allergies and asthma, and the Changs have devoted the bulk of their resources to that project. The moment Tanox succeeds in getting a drug on the market will be the culmination of years of struggle and dreaming. If Tse Wen’s idea works, the Changs could make an immense sum of money. Annual sales for asthma and allergy medications run to at least $5 billion.

However, all the effort that the Changs have put into Tanox will bear fruit only if they get to market before anybody else, and a company they once hoped to collaborate with is now sprinting to produce a nearly identical drug. In 1989, when Tanox needed additional funds, the Changs approached Genentech, in South San Francisco, to discuss the possibility of collaborating on the allergy remedy. One of the largest biotech companies in the world, Genentech is known for rigorous lab work that has resulted in an impressive series of discoveries, and Nancy Chang was attracted to the company for that reason. She directed a Tanox scientist, Fran Davis, to disclose Tse Wen’s findings after Genentech pledged in writing not to pirate any proprietary information. Davis did so in meetings and telephone conversations with Paula Jardieu, a scientist at Genentech who evaluated the importance of Tanox’s research. In 1990, however, negotiations broke down, and Genentech and Tanox agreed to go their separate ways.

Of course it would have been foolish to imagine that the hard-working immigrant is the only character in American business mythology that needs to be updated. Since the age of the robber barons, the high-stakes battles have usually been won by characters who represent the darker side of competition. If the Changs neatly typify the idealistic immigrant, Genentech can be seen as a modern version of the more pragmatic and more ruthless kind of company that often—for better or for worse—comes out on top. Though Genentech’s researchers regularly dazzle scientific circles with their exceptional results, the company’s management and marketing staff have earned the firm another kind of reputation: Genentech is known for playing hardball. Some of its marketing practices are so aggressive that federal authorities have questioned whether they may be unethical or even illegal. Not long after the negotiations with the Changs ended, the company launched a competing asthma project based on a nearly identical approach. The project was spearheaded by Paula Jardieu.

Genentech contended that it stole nothing from Tanox—that all the outside information it used was technically in the public realm—but Nancy Chang didn’t see it that way. While Tse Wen has dreamed up most of Tanox’s scientific achievements, it was Nancy who possessed the drive to strike out as an entrepreneur in the volatile and tumultuous field of biotechnology. Ultimately, it is not so strange that this shy immigrant from Taiwan would challenge a powerhouse like Genentech. After all, the California company was threatening to destroy everything she had worked to accomplish. In 1993 Tanox sued Genentech in state court in Harris County, alleging unfair business practices and breaches of contract and confidentiality.

As that suit and a countersuit subsequently filed by Genentech in federal court move forward, Tanox and Genentech are locked in a fierce race to get their products to market. For Tanox, the outcome means everything. Nearly all the biotech giants started out small and then ballooned into heavyweights on the strength of a single drug. In Nancy’s vision—which does not permit her to consider defeat—the asthma therapy that Tse Wen created is going to catapult her company into the ranks of the biotech titans. One afternoon late in January, she walked through the corridors of her company and pointed out its first laboratory facilities, built with money that she and Tse Wen had saved during the years that they worked for other people. Then she pointed out the labs constructed later, after a venture capital firm invested in the company. Finally, she opened a door that led into 10,000 square feet of plasterboard and exposed insulation, which she confidently announced would become the first pharmaceutical manufacturing site in Texas. “If this drug works,” Nancy says, lowering her voice to a dramatic whisper, “then this is where Tanox transforms from the little duckling into the beautiful swan.”

Both Nancy and Tse Wen Chang grew up in Taiwan, although they were raised in different circumstances. Nancy’s parents immigrated to Taiwan from China and were relatively wealthy; her mother was a surgeon, and her father was a civil engineer. Tse Wen’s family had lived in Taiwan for generations, and most of his relatives were farmers. Nancy attended the best schools; Tse Wen had no shoes when he went to elementary school. They met at a prestigious university in Hsinchu, where they had the same thesis adviser. They both applied to universities in the United States for graduate studies, and shortly after they were married, in 1973, they flew to the U.S. Tse Wen’s grandmother and some of her neighbors came to the airport to see him off because they didn’t know anybody who had flown in an airplane before.

From the minute the Changs left Taiwanese soil, everything was difficult. “I didn’t speak much English at the time,” says Nancy. She enrolled at Brown University, in Rhode Island, and then in her second year transferred to Harvard, where Tse Wen was a student. She says, “The first exam in anatomy, there were many, many questions I didn’t understand. One question, I encouraged myself to go and ask somebody. The word I asked about was ‘colon.’ I said, ‘What does this word mean?’ And the teacher made a big announcement: ‘Can you imagine this? That a student would come to Harvard and not understand this word?’ He wrote, really big on the blackboard, c-o-l-o-n. So I made a fool of myself, and I said, ‘I’m never going to make a fool of myself again.’ Then I studied very hard.” Nancy and Tse Wen hardly ever took vacations. They caught the earliest bus to campus in the morning and the last bus home at night, and they studied all the time.

In graduate school the Changs were introduced to the new field of recombinant DNA technology, which had been born of a single, momentous discovery made in 1973 by two Stanford University professors, Herbert Boyer and Stanley Cohen. Boyer and Cohen harnessed the ability of bacteria to copy the DNA instructions of other cells and replicate quickly, effectively transforming bacterial cells into tiny factories that could produce large quantities of organic substances. Until this point, collecting or manufacturing something like insulin was terribly expensive, but recombinant DNA technology made it feasible to produce lots of insulin relatively cheaply. The first biotech companies were created soon afterward, changing the face of medicine. Traditional pharmaceutical companies manufacture drugs made of chemicals, but biotech companies manufacture biologies, which are made of organic substances found in the body. If the biotech field lives up to its promise, it could cure many diseases that traditional medicine has failed to conquer.

After Tse Wen earned his Ph.D., he did postdoctoral research in immunology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he worked with immunologist Herman Eisen, who had done ground-breaking work on the structure of antibodies, the proteins that patrol the bloodstream looking for intruders. Tse Wen then went to work for Johnson and Johnson, where he helped develop an antibody that disables T cells. Because T cells are the immune system’s defense against foreign entities, they can sometimes cause patients to reject transplanted organs; Johnson and Johnson’s research led to a medication that helps patients accept transplants.

At Harvard, Nancy tried to coax bacteria into making silk in an early exploration of biotech’s new tools. After she graduated, she did postdoctoral research at Hoffmann–La Roche, a well-known pharmaceutical firm, where she was part of a team that used bacteria to produce alpha interferon. Alpha interferon is a protein normally made by white blood cells; since scientists have figured out how to make it themselves, alpha interferon has been used to treat hepatitis, among other things. It was cutting-edge science and a high-profile project. “I was on TV all the time,” says Nancy. “My professor would be on TV and then I would be on TV doing some experiment, just the student in a lab.” The attention was heady stuff for a reserved but ambitious young woman. And then Nancy’s aspirations were stymied, for the first time but perhaps not the last, by a young company called Genentech.

Before the alpha interferon project was finished, Hoffmann–La Roche decided to collaborate with Genentech—which Herbert Boyer had co-founded after leaving Stanford—because of its expertise with the tools of recombinant DNA technology. Genentech was hungry for business, and it had a lot of good scientists on the payroll. Its laboratories were set up like an assembly line, and Genentech’s people could do everything much faster than the researchers at Hoffmann–La Roche. Eventually Hoffmann–La Roche handed the entire project over to Genentech. It was a significant break for Genentech, and a big disappointment to Chang and her fellow researchers. But biotechnology is a quintessentially modern field, in which speed is paramount, and the lesson implicit in this early defeat was that the goals of individuals who work on this frontier will be subordinated to efficiency. Old-fashioned values such as fairness do not enter into the equation at all.

In the mid-eighties, as the bust tightened its stranglehold on Texas, the bottom fell out of the oil industry and real estate values collapsed, prompting enterprising businessmen to diversify their holdings. In Houston various people decided to invest in the medical field, most prominently George Mitchell, the oilman and real estate developer who built the Woodlands, a research complex and subdivision north of Houston. Spurred by this flurry of activity, institutions such as Rice University, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, and the Baylor College of Medicine formed technology transfer programs to push science out of academia and into the marketplace. They also started to hire innovators in new fields. In 1985 Nancy and Tse Wen received overtures to join the parade of Ph.D.’s who were migrating south and west.

At the time, Nancy and Tse Wen were working for Centocor, a small company in Malvern, Pennsylvania. Tse Wen was the vice president of research, and Nancy was the director of molecular biology. At Centocor, Nancy had collaborated with Robert Gallo, a prominent AIDS researcher at the National Institutes of Health, to produce the first recombinant DNA test for antibodies to HIV. “There were only a few companies in the biotech field then,” she says. “We were identified as leaders, so Baylor interviewed us. We came down for the weekend, met the department chairman and a couple of other people. Then Monday morning, back at Centocor, everybody knew. My boss called us into a meeting: ‘Why are you going down to Texas? Are you unhappy here?’ ” A bidding war began. Baylor offered to give Tse Wen a full professorship and tenure, and Nancy a job as an associate professor; Centocor offered Tse Wen a position on the company’s board. But there was one thing that Centocor could not offer: Since childhood, Tse Wen had dreamed of becoming a university professor. That December, the Changs moved to Houston.

Nancy and Tse Wen continued to work with Centocor on a consulting basis, and they performed some interesting experiments at Baylor. They were looking for innovative ways to treat people with AIDS. “We generated antibodies that can be of therapeutic value,” Nancy says. “These antibodies can neutralize the virus’s activity and stop the virus’s transmission. We achieved this in mice, and my chairman was so excited he called a press conference, announcing this was a breakthrough.” This time, the Changs decided, they should reap the benefits—not Hoffinann–La Roche, not Centocor, not Baylor. In 1986, with their personal savings and additional money from a few friends, the Changs built the first laboratories of their newly formed company on Stella Link Road, near their home in West University, to develop the AIDS treatment. They called the company Tanox (Nancy says she won’t explain what the name means until her goals for the company are realized). It wasn’t until the following year at Christmastime, when Nancy had no money to buy presents for her parents after meeting the company’s payroll, that the enormity of what they had done began to sink in.

To devote more time to Tanox, the Changs severed their ties with Centocor and Nancy quit her job at Baylor, though Tse Wen continued to work there part-time. While Tse Wen took the lead in the laboratory, Nancy assumed responsibility for the financial side of the business. She quickly earned a reputation in Houston’s business circles as a scrappy fighter. Nancy also pushed her employees—including her husband—to work their hardest, and not everyone was happy. “I think it’s always difficult to work under a husband-and-wife team, particularly when they don’t see eye to eye,” says a former Tanox employee. “Nancy was very domineering.”

Tanox’s AIDS therapy looks like it might prevent the AIDS virus from infecting somebody if it is administered very soon after the person is exposed—one possible application is to give the therapy to rape victims. The medication is now in the second phase of the Food and Drug Administration’s arduous clinical trials (the first phase tests a drug’s safety; the second phase tests safety and effectiveness; the third and final phase tests safety, effectiveness, and dosage). Almost immediately after the Changs founded Tanox, however, Tse Wen came up with another idea—a discovery that soon eclipsed the importance of the AIDS treatment in Tanox’s business plans.

For reasons that scientists have not fully determined, the incidence of asthma is on the rise. “Already, around twelve million people in the United States have asthma,” says Benjamin Interiano, the director of the Asthma Institute at the Baylor College of Medicine. “It’s the largest cause of school absences in children.” The disease inflicts a terrible sense of loss of control in those who suffer from it. Trying to breathe during an asthma attack is like trying to breathe while someone holds a pillow over your face. Every year, about 200,000 people in this country are hospitalized because of serious attacks, and about 5,000 people die. “You die of suffocation,” says Martin Wasserman, a pulmonary specialist who has asthma. “It’s caused by constriction and swelling in the lungs, and a pathological mucus that fills the airways. It’s not like mucus in your nose. It’s enormously thick, gooey stuff that doesn’t move along.”

Most of the irritants that set off an asthma attack—dust mites, pollen, animal dander, cigarette smoke—also cause allergic reactions, and scientists now believe there is a link between asthma and allergies. But a clear understanding of asthma is only evolving. Twenty years ago, asthma was viewed as a problem that occurred simply because muscles in the lungs contracted too much, obstructing the airways, and the disease was treated with bronchodilators, which cause the lungs’ muscles to relax. These drugs, administered by means of inhalers, make it easier to breathe, but they do nothing to address the underlying problem. “It’s a Band-Aid approach,” says Wasserman. “It’s like taking an aspirin for a brain tumor.” After scientists realized that asthma also involved an abnormal swelling of the lungs, clinicians began to prescribe anti-inflammatory drugs such as corticosteroids, but even steroids are not a cure. So there is a great deal of incentive for somebody to come up with a better solution.

Like thousands of his fellow Texans, Tse Wen suffers from severe allergies. He has had them since the late seventies, and they have gradually gotten worse. In 1987, the year after the Changs founded Tanox, Tse Wen had a sudden insight into how to tackle the root cause of his affliction. “I remember well,” he says. “I had the idea while I was in bed and couldn’t sleep. I got up and started talking about it. I do that kind of thing often.” He decided to develop a therapeutic antibody to a substance known as IgE, which seems to play a significant role in triggering both allergic reactions and asthma attacks. Antibodies to IgE already existed, but if anyone else had thought of trying to use them as a therapy for asthma and allergies, they probably dismissed the idea as unfeasible because the conventional wisdom argued against such an approach.

IgE itself is a type of antibody, one of the many immunoglobulins that are part of the immune system, and it was identified in the mid-sixties by Kimishige Ishizaka. IgE is produced by one type of B cell—an obscure cousin of the more famous T cell. It acts by circulating in the blood and in tissue and keeping watch for two things: allergens and the body’s weapons to dispose of allergens. These weapons are special cells that contain a potent cocktail of chemicals, including histamine (in the blood, these cells are called basophils; in tissue, mast cells). Antibodies are generally quite useful, but at least as far as its role in allergic reactions is concerned, IgE may be an exception to that rule. When IgE attaches to a mast cell or basophil and then grabs hold of an allergen too, the cell releases histamine into the bloodstream. Histamine is supposed to help (by causing sneezing and watery eyes to expel allergens), but the process is a distinctly uncomfortable one.

Using recombinant DNA technology, Tse Wen decided to create a therapeutic antibody that would chase down the problematic IgE antibody and keep it from attaching to histamine-laden cells; the therapeutic antibody would also stop B cells from making IgE in the first place. Most scientists had dismissed the concept because anti-IgE antibodies themselves usually cause allergic reactions—they attach to IgE just like an allergen would and set off the same cascade of troublesome symptoms. “It was too obvious that it was a dead end,” says Fran Davis of Tanox. “No one ever seriously considered it.”

But Tse Wen reasoned that if he developed an antibody aimed at the very spot on IgE where it attaches to cells that contain histamine, then his antibody would block IgE from binding to those cells. And his antibody could never mimic an allergen and bind to IgE already attached to a histamine-containing cell, because the antibody’s target would be inaccessible. If IgE was the key that opened the door of the cell that contained histamine, Tse Wen wanted to ensure the door stayed closed—with histamine safely locked inside—by making sure the key no longer fit into the cell’s keyhole. Because of the research he had done at Johnson and Johnson on antibodies that suppressed T cells, he realized that his antibody would attach to the IgE that was being secreted from B cells and act like a switch, turning the B cells off and halting their production of IgE.

So far, the concept has elicited a cautious enthusiasm among asthma experts. “I think it’s an attractive idea,” says Marshall Plaut, the chief of the Asthma and Allergy Branch of the National Institutes of Health. “It may have some value in regulating allergy-induced asthma.” Plaut wonders whether the therapeutic antibody will have any effect on asthma caused by viral infections, and he worries that getting rid of IgE might have harmful side effects. But if the antibody doesn’t prove hazardous, then there’s a good chance it will work.

Tanox employees consider Tse Wen’s idea one of those insights that turn prior understandings upside down. “It really is that sudden moment of realization: ‘Oh, yes, of course that’s true,’ ” says Fran Davis. “Because the idea was so simple, you’re vulnerable. For someone who works in the field, once someone tells you, it is so obvious. So we guarded this. From the day I joined, the whole concept was highly secret.” Other experts in the field are divided in their estimation of Tse Wen’s work. Some say the idea is too self-evident to be considered truly original; others credit Tse Wen with genius. In any event, to protect the idea, Tanox filed an application for a patent in 1987, and it is still pending. Subsequently, Tse Wen decided it was safe to publish news of his research, and in 1990 he published a general article about his antibody for a journal called Bio/Technology. It never occurred to him that by doing so he might jeopardize the prospects of his undertaking, let alone the prospects of the company that he and Nancy had founded. “It’s a common practice in the field to publish after you file a patent,” says Tse Wen. “It takes a lot to convince a corporate partner to work with you, and you need to publish to establish your credibility.”

By this time, of course, the future of the antibody and the future of the company had become intertwined. Almost as soon as Tse Wen decided to tackle IgE, Nancy made the asthma remedy Tanox’s primary focus. “In AIDS, the virus changes too fast, people do not understand the disease, and therefore ideas are all over the place,” she says. “If you’re infected with HIV, you may have twenty different strains in your system, but allergies are very different. If you’re allergic to peanut butter, you’ll make IgE against peanut butter. And the market is huge. So if you look at the risks and the return, there’s no question.”

The average biotech company is a mere thirteen years old and only 27 biologic products are on the market in the United States today, according to the Big Six accounting firm Ernst and Young. This is an infant industry. Like Tanox, the typical biotech firm has no income because as yet it manufactures nothing—the firm being so new, and biotech products taking so long to develop and gain approval from the Food and Drug Administration. A large front-runner such as Genentech generates annual sales in the hundreds of millions of dollars, but no biotech firm yet generates anything like the sales of pharmaceutical giant Johnson and Johnson, which reports annual sales in the tens of billions. Most biotech firms are tiny and suffer from a chronic need for cash.

In the past, scientists with an entrepreneurial bent found it fairly easy to get assistance from Wall Street, but the financial industry’s ardor for biotech stocks cooled after several bitter disappointments. (For example, Wall Street was thrown into an uproar after Centocor spent nearly $300 million to develop a product and then suspended clinical trials in 1993 because an unusual number of patients died during the trials.) So small companies made strategic alliances instead. These were usually with pharmaceutical companies or one of the larger biotech firms.

By 1988, the Changs had exhausted their personal savings, as well as an initial $4 million infusion from the venture capital firm Alafi Capital, which has invested in many prominent biotech companies, including Genentech, Biogen, and Amgen. Nancy tried raising additional venture capital but was unable to do so. “Any textbook will tell you anti-IgE is a potent allergen,” she says. “So venture capital companies were doubtful that this was a good approach. Only people who had the expertise to analyze the concept and see the finesse of the idea would say, ‘God, this is a gold mine.’ That’s when we started shopping at large companies.” Over the next year, Nancy approached about fifteen potential partners. Three firms, including Genentech and Ciba-Geigy Corporation, a Swiss pharmaceutical giant, expressed interest in collaborating.

Although Ciba-Geigy responded first and offered the most generous terms, Tanox felt drawn to Genentech because of the quality of its research. Among the company’s products are biologics that treat cystic fibrosis and reduce the risk of blood clots in heart attack patients. “Genentech is the premier good-science biotech company in the world,” says Fran Davis. At the same time, under the stewardship of G. Kirk Raab, a hard-driving CEO, Genentech had begun to acquire a reputation for aggressive, ruthless tactics. (Five years later, in 1994, Edmon Jennings, the company’s vice president of sales, would be indicted for alleged involvement in an attempt to bribe doctors to use Protropin, a growth hormone made by Genentech. Now, after reports that the company urged doctors to use its drugs for unapproved purposes or at unapproved dosages, the Food and Drug Administration has launched a broad inquiry into Genentech’s marketing practices. A spokesman for the company says that any inappropriately zealous behavior has been curbed.)

Tanox’s lawyers will not allow Nancy to speak in detail about events that are at the heart of the pending lawsuits, but according to court documents, Tanox and Genentech signed a confidentiality agreement in 1989. In it, Genentech pledged not to embark on a project that relied on information from Tanox without gaining permission from the Changs, so that the Changs would feel safe about revealing their ideas. Some of Genentech’s people visited Tanox that spring. That summer, the two companies exchanged information about Tanox’s product, and Tanox sent Genentech three milligrams of its antibodies to test. Throughout the courtship, Fran Davis was in regular contact with Genentech’s Paula Jardieu. “She thought this was a great idea,” says Davis. “I remember she was really excited about this prospect—maybe a little dubious, but excited.” (Jardieu declined to comment while the case is still pending.) Tanox and Genentech then tried to come to a business agreement, but the talks bogged down after Nancy insisted on more than Genentech was willing to offer.

“Tanox thought this was just fantastic, and Genentech thought that it was not,” says Stephen Raines, Genentech’s vice president for intellectual property. “There ended up being little basis for a cooperative effort.” In February 1990 Genentech withdrew from the negotiations. Gerald Birnberg, one of Tanox’s attorneys, summarizes the communication: “What they said was, Tanox didn’t want to accept their offer, therefore they wished Tanox luck, and they were going to spend their development dollars on something other than an anti-IgE antibody.” Later that year, Tanox signed an agreement that gave Ciba-Geigy the license to its antibody, thus guaranteeing Ciba-Geigy a generous share of any future profits in return for providing Tanox with the funds to develop the product.

Two years later, the Changs decided to separate, and the following year, they got a divorce. Nancy says only, “We’re good friends. We put the kids in front of us, and we put the company in front of us. We couldn’t live together, but we certainly respect each other. Neither of us remarried—I’m sort of married to the company right now.” And Tse Wen says, “In general, our working relationship is better now since the separation. Now both of us can function more or less independently. Both of us have our hearts in the company.”

In 1992 the Changs got a scare when they learned that Genentech had initiated its own anti-IgE project, but they were reassured after learning the project was substantially different from theirs. What the Changs didn’t find out, at least not right away, was that after Genentech’s project ran into trouble, the company changed course. Nancy was given her first hint of this change the following year when a Wall Street analyst called to say he had just met with Kirk Raab, the CEO of Genentech, and that Raab was planning to introduce an antibody that sounded a lot like Tanox’s. Later that year the Changs’ fears were confirmed when Genentech scientists described their new line of research in the Journal of Immunology. This time, Genentech’s work bore a great deal of similarity to Tanox’s. “How could this happen to us?” asks Nancy, fuming at the betrayal. “We trusted them. We gave them an open book about the technology. We trusted them.” Every adviser counseled Nancy to take conciliatory steps—Genentech was too big an opponent, they told her, and the company’s reputation for strong-arm tactics made it even more formidable. Nevertheless, late in 1993, she filed suit.

As far as Genentech is concerned, the two projects are similar, but not because Genentech stole anything from Tanox. Genentech says most of Tanox’s work isn’t proprietary, largely because of the article that Tse Wen published about his findings. “We picked up a program directed toward asthma and allergies with the goal of developing a product, but we didn’t take theirs,” says Stephen Raines. “As a matter of fact, there was an awful lot in the public domain. Much of their stuff had been published. Our people have found in the prior literature essentially everything that they brought to the table.”

Nancy bristles when told of Raines’s remarks. “That’s like saying, ‘I made an invention and then the invention was made public, therefore everybody else can steal the invention,’ ” she retorts. “That’s not why you have patent law.” Whether Tanox’s idea is proprietary or whether Genentech has the right to use Tse Wen’s published writings in formulating its product is now a matter for the courts to decide.

Last December, one year after Tanox initiated legal proceedings against Genentech, Fran Davis and Paula Jardieu met at a hotel in New Orleans, where they delivered back-to-back speeches at a conference on allergies and asthma. They were there to drum up enthusiasm for the products they are hustling to develop. Davis, who spoke first, was dressed in a black suit with brass-colored buttons, and her hair was in a bun; she could have passed for a librarian. She stressed the original nature of her company’s research. “This process was invented by our vice president of research and development, Tse Wen Chang,” Davis told the audience. “This strategy had not previously been seriously considered.” She added, “The invention was disclosed to Dr. Jardieu of Genentech, who now is following in our footsteps.”

Jardieu is petite, with a kind of worn beauty and an upturned nose. She was dressed in a snazzy black skirt and jacket and cut a more fashionable figure. At the same time, Jardieu is a serious rival: She previously studied with Kimishige Ishizaka, who discovered IgE, and is regarded as one of the foremost experts on this part of the immune system. Jardieu talked at length about scientific discoveries that laid the groundwork for an anti-IgE antibody. “Looking at the literature going back a couple of decades, it’s pretty obvious that people were very aware that allergens were somehow correlated with asthmatic symptoms,” said Jardieu, implying that the idea to treat asthma and allergies in this fashion should have been self-evident.

Afterward, many scientists at the conference agreed that Jardieu had won the skirmish. Her experiments were elegant, and she had displayed an expert’s command of her subject, while Davis had tailored her remarks for a less knowledgeable listener. It was, as even Davis would concede, nice work. In the meantime, Genentech has taken the lead in the race to market, roaring into the second phase of clinical trials last July, five months ahead of Tanox. The soonest that either company anticipates concluding its clinical trials is sometime in 1997. Most observers are betting that given its scientific prowess, Genentech will win the race. Unless, of course, the courts intervene.

The dispute between Tanox and Genentech is scheduled to go to trial next year. Tanox alleges that while Tse Wen may have disclosed the outlines of his idea to the public, Genentech nevertheless violated the terms of the confidentiality agreement. Genentech’s strategy seems to be that the best defense is a good offense: Two months after Tanox filed suit, Genentech retaliated with a countersuit in federal court. This past February, Genentech sued Ciba-Geigy too.

Genentech alleges that Tanox’s project is itself a form of theft, because it violates Genentech’s Cabilly patent, which gives the company broad rights over the technology used to make antibodies by splicing together human and animal genes. Since Genentech originally filed for its patent, the methods of manufacturing antibodies have evolved, and it is not clear whether the more sophisticated techniques Tanox is using fall within the domain of Genentech’s patent. In fact, where biotechnology is concerned, patent law is something of a muddle because many significant patents are just now being challenged in the courts.

Tanox’s lead attorney, Michael Madigan of Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer, and Feld, says he is counting on the tendency of Texas juries to side with small local businesses wronged by large out-of-state corporations. Genentech’s Raines admits, “There are advantages to being the small guy in going before a jury, but I would hope at the end of the day that the jury would get to the merits of the arguments. Our patent clearly covers Tanox’s product, and I would hope that a jury wouldn’t say that just because this is a Texas company, it doesn’t infringe.”

In many ways, the lawsuit is Nancy’s biggest gamble yet. After the suit was filed, several of her directors quit and about a dozen of her employees walked out amid rumors that Tanox could never survive the ordeal. But to her, the logic of the situation was obvious. “Everybody, including my partners, said we have to succumb to the power and the money and the pressure and give up, and we did not,” she says. “We believe in what we are doing. This is our dream. How can we give up our dream? It is everything.”