Chief Brown started his shift early that day. There were demonstrations planned in Dallas and cities across the country, and he knew his officers faced the difficult task of protecting protesters, some of whom were seething at police. The day had passed relatively peacefully, though a few people had been arrested at afternoon protests. Brown stayed late to monitor the evening march through downtown. Everything seemed to be going smoothly, so he decided to head home for the night. Before leaving, he told David Pughes, his second in command, to call him when the last protesters left the area. Brown made it to his condo across the street from police headquarters and had just taken off his gun belt when Pughes called. Brown could hear that he was out of breath.

With all that’s happened in the world since then, it’s easy to forget just how angry and tense the country felt in July 2016. On July 5, a video went viral showing two white police officers in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, fighting a 37-year-old black man named Alton Sterling outside a convenience store. At some point, they appear to have him pinned on the ground when one of them yells that Sterling is reaching for a gun. Then the officers fire six times, and the video shows Sterling on his back, blood soaking through his red polo shirt as he dies in the parking lot.

The very next day, another video circulated, this one from Facebook Live, showing the immediate aftermath of a police shooting in suburban Minnesota. When the video begins, a 32-year-old black man named Philando Castile is behind the wheel of a car. He is moaning and covered in blood. His girlfriend explains that they’d been pulled over for a broken taillight, that Castile had told the officers he had a license to carry a gun, and that the officer had opened fire. As the girlfriend narrates, a police officer outside the car has his gun drawn, and he’s shouting, sounding panicked. The video ends with the girlfriend handcuffed in the backseat of a police car, screaming while her 4-year-old daughter—who has just witnessed everything—tries to reassure her. “It’s okay,” the little girl says to her crying mother. “I’m right here with you.”

In the middle of a divisive presidential election, the videos spread and the names Alton Sterling and Philando Castile began trending on Twitter. The public outrage was immediate. These were two black men killed on camera by police in two days, adding to a list that already included the names Tamir Rice and Eric Garner and Eric Harris and Laquan McDonald and Walter Scott and John Crawford III.

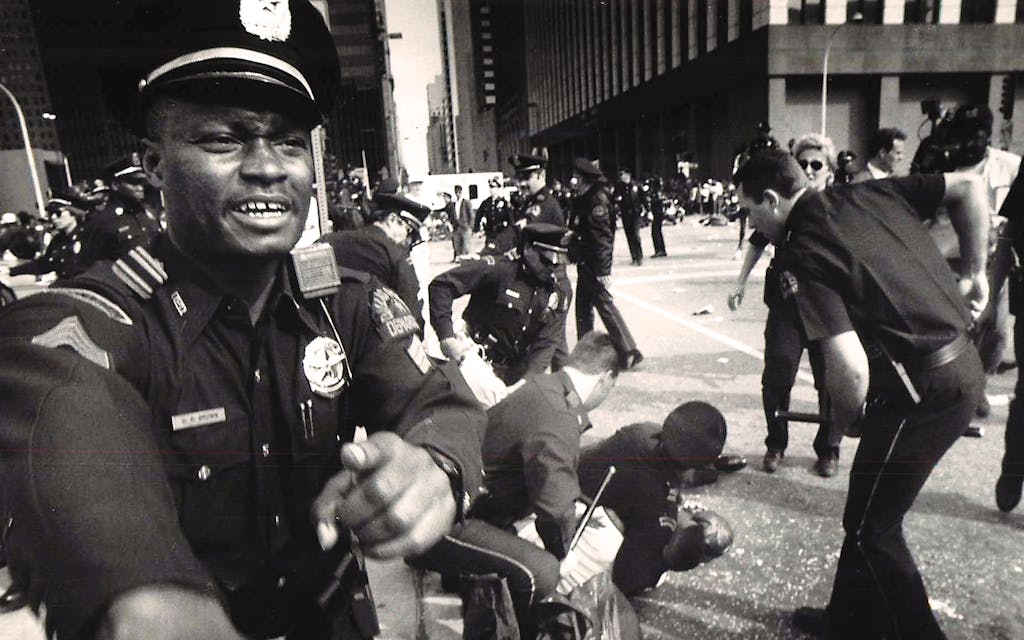

On July 7 activists took to the streets all over America, carrying signs and chanting, among other things, “No justice, no peace!” About a thousand protesters, surrounded by a hundred or so police officers, marched along Main Street in Dallas. There were raised fists and loud declarations of indignation, but there was no aggression. As they marched, a few of the protesters even stopped to pose for photos with police officers. Brown was actually feeling relieved when he got home that night, like he’d “dodged a bullet”—until he received that call from Pughes. He knew right away that something was wrong. “It was the worst news you want to hear as a cop, that you have officers down,” Brown told me.

As the crowd downtown had begun to disperse, a 25-year-old Army veteran named Micah Johnson had driven his black Chevy Tahoe around the protest and onto Lamar Street, which had been blocked off by police. He parked sideways, facing the doors of El Centro College and left his hazard lights flashing. A stout five foot eight, he wore a brown body-armor vest and carried a Saiga AK-74 rifle with several thirty-round magazines. Because there were open-carry activists at the march also carrying rifles, Johnson didn’t stand out. He may have even talked with some officers before opening fire. A grand jury is still examining the events of that night, so some details, including more than 170 hours of body-cam footage, haven’t been released to the public. But the reports that have been made public, along with shaky cellphone videos and blurry security camera footage, reveal some of what happened next.

At 8:58 p.m., Johnson shot into a passing police car, then fired at officers gathered at the edge of the protest. At first, nobody was sure where the shots were coming from. The sound reverberated off buildings and bullets skipped off the pavement. The calls going out over the police scanner were calm at first: “Code three. . . . Shots fired, officer down.” Then they quickly escalated: “We got a guy with a long rifle. We don’t know where the hell he’s at!” Within three minutes, officers were yelling into the radio, calling for SWAT and using the phrase “low sick”—a term that indicates an officer is close to death.

At the corner of Lamar and Main, Johnson shot and killed Officer Patrick Zamarripa, age 32; Officer Michael Krol, age 40; and 48-year-old Senior Corporal Lorne Ahrens, whom the Dallas Morning News would later describe as “so kind that he once bought a meal for a homeless man and his dog.” At the same intersection, Johnson wounded three other officers and a civilian, Shetamia Taylor, who’d brought her four sons to the protest; after she was shot in the leg, Taylor tried to shield her kids from the bullets.

As the sound of gunfire crackled through the streets, protesters broke into sprints, ducking behind parked cars. Johnson shot out the glass doors of the community college building and tried to get in. He wounded two campus police officers inside, but they fired back, sending the shooter scurrying away.

Johnson made his way down Lamar Street, darting between concrete pillars until he encountered Brent Thompson, a 43-year-old transit police officer who had gotten married just two weeks earlier. When Johnson fired at him, the officer retreated behind a pillar for cover. Johnson fired a few rounds to the left of the pillar, forcing Thompson to instinctively take a step back. Johnson moved quickly to the right of the pillar and shot the officer from behind. With Thompson down, Johnson stood over him and continued firing.

Then the shooter went around the corner of the El Centro building, to a different entrance. He went up a flight of stairs, through a library, and down a hall. When he came to a set of windows overlooking Elm Street, he fired at officers on the ground, injuring one and killing another, 55-year-old Sergeant Michael Smith.

About fifteen minutes after the shooting started, with five officers dead or in critical condition and several more wounded, police cornered Johnson at the end of a long hallway on the second floor. They sealed off exit routes and evacuated the college. They didn’t have a line of sight, but at least they knew where Johnson was. Pughes called Brown to give him an update.

By then, the chief was on his way to meet the mayor at city hall. Brown managed a command center there with dispatchers on hand and staffers to coordinate with ambulances and hospitals and SWAT teams. Tables were pushed together, and the quiet room soon filled with the chatter of people working.

Brown made sure people were updating social media feeds with the latest information, some of which turned out to be wrong. At the time, the police still thought there was more than one shooter, so there was also a search to coordinate. More politicians were showing up too, so he had to manage that as well. He looked around at the bustle. At one point, there were about forty people in the room. People who were scared and confused and looking for answers. No one knew what the coming hours and days might bring, if there would be more violence or if the city would divide along racial lines and turn on itself.

That’s when it dawned on him. Brown remembers thinking right then that his entire life—all of his experiences and assignments, all of the tragedy and pain he’d endured—had been preparing him for this singular, seminal moment.

Brown isn’t given to exaggeration. His demeanor is solemn, deliberate. When he talks to you, he’ll rub his chin in contemplation and peer at you through the thick frames of his glasses, sizing you up. Dallas mayor Mike Rawlings worked closely with Brown for five years. “He’s not a warm, fuzzy guy,” says Rawlings, who also spent most of the night of July 7 with the chief. “He was all business with me day in and day out. He’s not a hugger. But he’s a very loyal, heartfelt man.”

Brown rarely tells jokes, but he still manages to make people laugh with the earnest and self-deprecating way he talks about how, back in high school, he approached girls he liked, or the way he pulls out old goofy pictures of himself or casually mentions that he once played Captain Von Trapp in a production of The Sound of Music. Mostly though, he’s calm, blunt, and matter-of-fact. That’s the way he talks about his life.

Both of his parents were born in the basement of Old Parkland Hospital, because that’s as close to a maternity ward as black babies got in Dallas during the thirties and forties. The old hospital has long since been converted into posh office space, and sometimes Brown parks his black Land Rover in the same basement—a life coming full-circle, the way he sees it.

Brown was born in the newer Parkland three years before JFK was shot and Dallas became known as “the city of hate.” He grew up in the Oak Cliff section of the city, the middle boy of three. His father was in and out of the picture, and his mother, Norma Jean, managed apartment complexes, so they moved around South Dallas often. Parts of the area had a reputation for high crime rates, but when Brown thinks of Oak Cliff, he thinks of the bucolic, tree-lined streets and the rolling hills and hardworking neighbors.

He was a quiet, serious kid. “I do think he has a sense of humor,” a longtime acquaintance once told the Dallas Morning News, “but I think he disguises it fairly well.” It wasn’t that Brown was particularly unpopular as a child; he just preferred spending time with adults. People told him he had an “old soul.” He figures that’s why he always liked listening to his mother and his great-grandmother Mabel tell stories and impart advice. He still remembers the things they’d say: Make something of yourself. Not everybody that smiles at you is on your side. Don’t get too high on your horse.

As a teenager, he interned for an attorney who would become the first black district judge in Dallas, and Brown decided he wanted to be Perry Mason. In his senior year at South Oak Cliff High, he was voted both Most Likely to Succeed and Most Intellectual.

A mix of financial aid and scholarships allowed him to attend the University of Texas at Austin in 1979. Every time he came home from school, though, he noticed his neighborhood looking worse. More drugs, more guns, more violence. In 1983 he decided to change his plans. By then he had a wife and a baby on the way, and Brown wanted to help clean up Oak Cliff. He dropped out of UT and applied for a job as a Dallas police officer. He figured he’d serve for a few years and then go to law school to be Perry Mason. The first time he ever held a gun was at the police academy.

In the mid-eighties, crack had come to South Dallas, and the area became one of the most violent places in America. Brown liked busting drug dealers—he was a true believer in the war on drugs at the time—but his partner and best friend, Walter Williams, encouraged him to think beyond his own neighborhood. Williams was twenty years older than Brown, and he pushed his younger partner to think more critically about the way police are trained, the way leadership operates. In the mornings before work, they talked about what they might do differently if one of them were in charge one day. The idea seemed ridiculous to Brown at the time. “Walter challenged my motivations,” he says now. “He had a more comprehensive view. He planted the seed in me, the idea of thinking of bigger things, caring in a bigger way.”

One night in 1988, Brown was called to the scene of an officer-involved shooting and immediately recognized his friend’s glasses on the ground, broken and covered in blood. Williams and a young officer he was training had been responding to a domestic violence call when a man hiding outside the apartment ambushed them and shot Williams in the forehead. When Brown realized who the downed officer was, he drove to the hospital.

He saw his best friend, still and silent, attached to a series of machines. Walter’s wife, Joanne, sobbed and asked Brown to go to her house, to look after their three kids. Just 27 years old, he didn’t want to be the one to tell them what had happened to their father, but he went anyway. And after breaking the news, he sat with them all night, until, one by one, each of them fell asleep.

He remembers watching the children wail a few days later, as their father was lowered into the ground. He remembers the pain and despair welling in his chest. But he wanted to stay strong for the family, so he waited until he got home to cry.

He’s always been a private man. City officials tell stories of seeing him out at restaurants, dining alone. For years he watched as other officers befriended reporters and politicians, but that wasn’t his style. He says the only reason he’s sharing his story now, in extended interviews and in a new book, Called to Rise, is because he thinks he might be able to help people experiencing some of the same things he has. He’s not particularly introspective, and he doesn’t talk much about what it means to be a black police officer in modern America. But his family has seen the damage that drugs and unchecked mental illness can do. He’d been personally affected by gun violence long before July 7.

On one of his trips home from college, Brown noticed his brother Kelvin, who’s three years younger, acting strangely. There was an “unsettling gaze” in his brother’s eyes, and Brown worried for him, but he didn’t know what was wrong and didn’t mention his concerns to his relatives. “My family didn’t talk a lot about people struggling with whatever they were struggling with,” he says. “We stayed hopeful that our love would make it okay, that prayer for them would make it okay, without interrogating them, like ‘What are you doing? Where are you going?’ I was hopeful, even though I knew.”

Brown convinced himself everything would be fine. Kelvin had a family, and by the early nineties, he had a job as a truck driver. “I didn’t want to see the signs,” Brown says. He didn’t want to accept that his family had a problem. “I kind of blinded myself.”

At the time, nearly ten years into his career, Brown was working his way up the ranks of the force. His first true supervisor position came when he was transferred to the 911 center, where he managed a team of mostly women—and learned that merely dictating orders wasn’t an effective leadership approach. He’s still friends with several of those women today, and they joke now about how personality clashes taught him early on that “working collaboratively, persuading your people, is always better,” he says.

“Time doesn’t heal; it merely dulls the pain, and years later, at last dims your memory of it.”

He was at the 911 center one night in 1991 when someone told him his mother was on the phone. That worried him. His mother had never called him at work, and now it was after midnight. When he took the phone, all he heard was his mother weeping. He asked her several times what was wrong before she got the words out. “Kelvin was killed.”

To this day, Brown doesn’t know all the details. He could have called the Phoenix Police Department and asked, but he couldn’t bring himself to do it. He knows the basics: Kelvin, 28, had been driving through Arizona and found a crack dealer in Phoenix. He bought and smoked some, but he didn’t feel high, so he was convinced he’d been ripped off. When he went back to the dealer, there was a fight and Kelvin was shot.

After Walter Williams was murdered, Brown had begun to question his faith. He’d felt that because he was fighting for good, he’d be protected and rewarded by God. Why would God allow a black man from Brown’s own neighborhood to ambush his best friend? Williams’s death “shook me to my core,” he writes in Called to Rise. But members of his church persuaded him to move forward with prayer. And he took the same approach three years later, when his brother died.

“You don’t ever really get over the loss of a loved one,” he writes. “I’d learned that in the years following Walter’s death, and I learned it again now, as I grieved for Kelvin. In your sadness, you just keep getting up every day, breathing your way from one moment to the next. Time doesn’t heal; it merely dulls the pain, and years later, at last dims your memory of it.”

When he thinks about his brother’s death now, he’s struck by the fact that it could have been him instead. It sounds crazy, but not to him. As a teenager, Brown says he once took a hit from a joint, but he didn’t like the taste so he didn’t try it again. He’s convinced that if he’d been a few years younger, living in South Dallas during the crack epidemic, his whole life would have been different.

“Kelvin has a son and a daughter that are going to hear this story,” he tells me. “So I want them to hear: how you look at your father and how you look at me shouldn’t be much different, except for me leaving and going to school and being away from that environment. I would have tried it. I likely would have been addicted. My life is about going all in when I decide to do something. I don’t halfway do something.”

Brown had just left college when his son, David Brown Jr., was born. Everyone called him D.J. The boy was five when Brown and his mother divorced. Brown eventually remarried, to a fellow officer named Cedonia, and they have a daughter. But Brown saw D.J. every other weekend. It wasn’t always easy to make time as he went back to school to finish his degree and continued to ascend the ranks of the force.

After the 911 center, he spent seven years in SWAT, often in the middle of the most intense situations the department faced. He also did a stint on the community policing team, a group assigned to strengthen the department’s ties with neighbors and leaders in troubled areas. He was a skeptic at first—he thought officers should spend their time chasing bad guys, not doing “soft policing”—but the assignment proved to him that real trust building with a community can have a dramatic effect. (In 2005 Brown was promoted to second in command under his predecessor, Chief David Kunkle.)

In 1996, D.J., at that point a teenager, was fighting with his mother, so he moved in with his father. Brown describes himself as a disciplinarian. Chores done. No back talk. Homework turned in on time. Father and son had what Brown calls “a few bristles” early on, but D.J.’s grades and his attitude improved through high school. He played trombone in the school band, and Brown was there for every one of his son’s concerts.

D.J. enrolled at Prairie View A&M University, outside Houston, but he had trouble adjusting and returned to Dallas after just a year. In 2003, D.J., now a father himself, was arrested on suspicion of selling marijuana in Waxahachie. He pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor drug charge.

“I’m much more impressed when you make mistakes, how you respond to it,” Brown told reporters years later about the incident. “It speaks to the kind of man he is. He continued his education, he’s gainfully employed in spite of some of the mistakes that he’s made.”

In the fall of 2009, Brown got a call in the middle of the night. All he heard was the sound of his then 26-year-old son screaming. But when Brown arrived at the apartment, D.J. and his girlfriend seemed perfectly normal. “We’re fine,” she told him. It was “nothing,” D.J. said. The baby was sleeping soundly, as usual.

But a few minutes later, D.J. began talking unusually fast. Then he started convulsing. Brown called 911 and followed the ambulance to the hospital. Because D.J. was an adult, doctors wouldn’t tell Brown anything without his son’s permission. The girlfriend didn’t want to upset D.J., so she didn’t tell his father anything either. Brown asked D.J. what was happening, but there was no response. His son just stared off, expressionless. Brown stayed by D.J.’s hospital bed, praying. He thought maybe it was epilepsy. He says that D.J. wouldn’t talk much about what happened that night.

In May 2010, Brown was sworn in as the second black police chief in Dallas history. At the swearing in, he was surrounded by his family and the scores of men and women he’d served alongside and commanded for more than two decades. True to form, he told reporters at the time that he’d have preferred a smaller, more private ceremony.

Crime in Dallas had declined for five straight years. As number two in the department, Brown had helped implement many changes during Kunkle’s tenure, including an increase in community policing and a focus on statistical analysis to help target high-crime areas. When he took over, Brown wanted to double down on all of it.

On Father’s Day that year, a few weeks after he became police chief, Brown was sitting in church when his cell phone rang. He let it go to voice mail. “Everybody knows I don’t answer the phone in church,” he says. The message was from the police chief in the Dallas suburb of Lancaster. One of his officers had responded to a call at D.J.’s apartment, and while everything was apparently okay now, D.J.’s girlfriend was going to stay overnight with her parents.

Brown called his son and left a message asking for a call back. He didn’t mention the call from the Lancaster chief. “We were planning to get together anyway,” he says. “We were gonna go out and talk about it, and I was going to give him some fatherly advice about relationships and ‘Go say you’re sorry’ and that kind of thing.” Around 2 p.m., Brown fell asleep. The call that woke him up a few hours later came from a Lancaster detective.

What Brown didn’t know at the time was that D.J. had been living with bipolar disorder. That morning his girlfriend had called 911, but when police arrived, D.J. seemed fine. After his girlfriend took their baby to her parents’, D.J. was spotted at the apartment pool. Witnesses said he was acting strange, dancing and humming, wearing only boxer shorts and sunglasses. At some point he disappeared and returned with a handgun. (Reports would later show he had PCP in his system.)

He approached a car moving through the parking lot. Jeremy McMillan, a 23-year-old father of two, was driving his Mitsubishi Galant into the complex. He was taking his girlfriend, his 3-year-old daughter, and his infant son to meet his sister. The couple were chatting, going over a speed bump, when they saw a man with a gun.

D.J. fired at least three times into the car, hitting McMillan in the head and neck, and blood splattered over the children in the backseat. The car kept rolling, coming to a stop against a garbage can, and D.J. ran back to his apartment and picked up a rifle.

He got in his car and was trying to drive away when Lancaster police officer Craig Shaw, a father of two, arrived on the scene. D.J. fired at Shaw several times, hitting him in the head and fatally wounding him. Within minutes other officers arrived and shot D.J. at least twelve times.

“It’s hard to find the words when you hear something like that,” Brown says. “You don’t pass out, but it takes your consciousness away.” Some part of him just couldn’t believe it. “I’d never seen him with a gun. He’s not acclimated to guns because I’m a cop. I don’t own but one gun, my sidearm. I never took him out to shoot, none of that.”

His phone began to ring as friends and relatives saw reports on the news. Every conversation started the same way. “Tell me they’ve got it wrong.” Or “This can’t be true.”

Because two other people had died—one of them a police officer—Brown never felt comfortable grieving in public. “I started almost being split in half,” he says. A preacher arranged for him to meet the families of the men his son had killed. Brown doesn’t remember much from that time. He recalls saying that he was sorry and that he didn’t raise his son that way and that he knew his words were inadequate.

He stayed at home and didn’t answer the phone. He felt as though he was going to die from the grief. Every breath felt as if it could be his last. He couldn’t eat, couldn’t sleep, and told the people closest to him on the force to stay away. He would get distracted from the pain for a second and then remember it all over again. He existed in a fog.

He couldn’t even quite describe the state he was in. A few years later, he was sitting in an optometrist’s office getting his eyes checked when he saw a poster listing the warning signs for glaucoma. “I was like, ‘That’s how I felt!’ Like you’ve got this narrow space,” he says, lifting his hands to his eyes like he’s peering through an imaginary set of binoculars. “It was dim everywhere, except where I was looking. Everything else was a real dark place. I feel like I had glaucoma for a long time.”

He wondered where D.J. had gotten the guns. He wondered why he’d never known about the mental illness. He wondered if he should have done something different after the hospital episode. He expected the city management to ask for his resignation simply because the situation looked bad. But that didn’t happen. Two weeks later, he returned to work.

For years, Brown wouldn’t discuss his son in public. People around him noticed that he seemed different, more distant, even more serious than he had been. Privately, Brown wanted to know why God had done this to him. He wanted to know what purpose all of this pain could possibly serve. Looking back now, though, he believes these tragedies were, in part, God preparing him for what was to come. There were other trials too, like the teen who tried to blow up the Fountain Place building downtown. Or the guy who attacked police headquarters in an armored vehicle. In that case, the only thing that stopped the gunman was a bullet from a .50-caliber sniper’s rifle, which Brown had to be persuaded to obtain for the force. He also had to be persuaded to send some of his officers to an explosives school, something that would come in handy later.

He understands the concerns about the militarization of police. On SWAT, he was on the front lines of the issue well before it became a national discussion. So while he sympathizes with the community’s fear of military-style armaments, Brown also sees it from an officer’s vantage point, that if there are tools that could save your life, you’d like to have them. “You only need to get shot at one time, and you start thinking about the world differently,” he says. “Those life-and-death moments where, man, we need to have this or we need to have that, so the next time I have a better chance of surviving if I ever make it out.”

Another lesson came in 2012, in an area of Dallas known as Dixon Circle. That summer, a white officer shot an unarmed black man. Police were responding to a report that someone had seen a man being forced into a house there. When officers arrived, the men in the house ran. An officer chased one of the suspects over three fences, through a series of backyards, and into an old horse barn. There, a witness saw the men fighting. The officer, exhausted from the chase, pulled his gun and fired three times.

A rumor went through the neighborhood that the man had been shot in the back, and by that afternoon, hundreds of people had gathered to protest. This was two years before the events of Ferguson, Missouri, but even then police knew how combustible the situation could be.

Brown decided to speak to the public and to be as transparent as possible. At a press conference, he explained the facts as he knew them—that the officer had shot the man in the stomach—but instead of immediately defending his officer, he said things like “We will now second-guess him.” He said he would review the department’s chase policy. He asked for an expedited medical examiner’s report, which usually takes weeks, and implored pastors and members of the Black Panthers in the area to calm the tensions. He believes these are the reasons the unrest didn’t escalate, why there was no riot. (An investigation revealed the 911 call came from a rival drug dealer looking for revenge, and a grand jury later cleared the officer.)

Throughout his tenure, he made an effort to hold officers accountable for misconduct, firing some despite objections from inside the force. He referred several cases to the district attorney’s office, for potential criminal charges. That irritated police unions, but it earned him a measure of trust in the community. Meanwhile, crime declined steadily for five more years under Brown, even as his officers left in droves for suburban forces that paid better, and morale on the Dallas force was low. Brown actually advocated at times that some of the money that would have otherwise gone toward the department be reallocated to things like schools.

In the beginning of 2016, though, crime rates—most notably the murder rate—rose dramatically. Experts tossed around potential explanations, from lagging 911 response times to competing Mexican cartels. Brown decided that, whatever the reason for the increase, the department needed to act swiftly. He immediately moved more officers to night shifts, which was especially unpopular among veterans and single parents on the force. Morale sank even faster, and there were even more defections.

By the beginning of that summer, every one of the local police unions, including the Black Police Association, was united in calling for his resignation. It seemed all but certain that he’d soon be fired or forced to resign. But that all changed on the night of July 7.

Micah Xavier Johnson grew up in Mesquite. His parents divorced when he was four. He graduated from John Horn High School in 2009 at the bottom of his class. But his parents have said he was a patriotic boy and dreamed of one day being a police officer. After high school, he joined the Army Reserves and was called to active duty in Afghanistan in November 2013. Reports since released by the Army show that he was viewed as a loner. He was removed from Afghanistan and discharged from the Army after being accused of sexual harassment and stealing underwear from a female soldier. In the civilian world, his co-workers have said he had anger issues. Back in Texas, he lived with his mother and his disabled older brother. Neighbors sometimes saw him practicing what looked like combat drills in the backyard. He also started amassing weapons.

People who knew him have told reporters that he wasn’t particularly interested in social issues before he deployed, but at some point he “liked” several black nationalist groups on Facebook. His profile picture was of him in a dashiki with his fist raised. He attended a few meetings of various organizations; one in Houston asked him not to return. Activists in Dallas, too, declined his offer to help with a protest in June 2016.

By the time police had him pinned at the end of the hallway in the El Centro building, Johnson was already injured. He’d stopped twice in the building to write the letters “RB” on the wall in his own blood—it’s not clear why.

Chief Brown was getting live updates from officers on the scene. Every few minutes, he’d brief the politicians at city hall. Brown says Johnson was mocking officers. He asked them how many he’d already killed. He said he’d planted bombs all over downtown, and he could detonate them at any moment. At one point he demanded to talk to a black officer. The negotiator he’d been speaking with was black, but he “played along,” as Brown says, lowering his voice and pretending to be someone else. The officer asked Johnson if he liked R&B. Brown says Johnson yelled back down the hall that he liked Michael Jackson, then proceeded to sing.

It seemed all but certain that he’d soon be fired or forced to resign. But that all changed on the night of July 7.

After nearly three hours, the chief and mayor agreed that they needed to hold a press conference. Before he headed out to talk to the media, Brown told a SWAT commander to come up with a plan to end this. He remembers saying, “Use your creativity.”

He walked out to a row of cameras and, in a quick, concise manner, explained that eleven officers had been shot and that at least three were dead. He said they were negotiating with a gunman, but they thought there might be multiple shooters. He ended with a curt, “I have to get back real quick.”

Then he got back on the phone with SWAT team commander Bill Humphrey. Brown says he nixed the idea of charging down the hallway for a shoot-out or sending officers down with a shield; he didn’t want to lose any more cops that night. Humphrey had a third idea. They could send in a robot carrying an explosive and blow the shooter up.

No department in the country had ever done anything like this. Brown worried that Johnson might shoot the bomb while it was still close to the officers. Or that the robot would get stuck somewhere—an explosive new obstacle. Or that they’d accidentally blow up a load-bearing beam somewhere and take down the whole building. But this plan still seemed like the safest option for officers. He gave Humphrey the go-ahead.

The robot, a Remotec Andros Mark V-A1, costs somewhere around $150,000 and weighs about eight hundred pounds. They attached a pound of C-4 to the little metal arm and set up both manual and remote detonators. The negotiator was told to distract Johnson with conversation so he wouldn’t see the robot. The negotiator asked the gunman why he disliked cops so much, and Johnson unleashed a tirade.

He did look around the corner in time to see the robot approaching, but by then it was too late. At 1:28 a.m., the bomb went off. You could hear the explosion nearly a mile away. It didn’t take down the building, but it did destroy some computer servers. It also left Johnson lifeless, covered in dust and sheetrock.

Brown got the call telling him that the plan had worked just as he and the mayor were getting to Parkland, the first of two hospitals they would visit that night. By the next morning, police had finished searching downtown and hadn’t found any bombs. They also never found evidence of a second shooter. At Johnson’s house, in Mesquite, they found journals filled with notes about combat strategy and incoherent ramblings. Brown says there was evidence that Johnson had been planning an attack on officers since before the Sterling and Castile videos, and that the Dallas march had simply provided an opportunity.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack, it seemed possible that the shooting would further divide the country. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick blamed Black Lives Matter supporters for instigating the attack. President Barack Obama called for stricter gun control laws. And the largest police union in the country criticized the president and wanted the shootings to be investigated as a hate crime.

But Chief Brown, whose reaction would be perhaps the most important, took a different approach. At a press conference in the morning, he stepped to the microphone with a black stripe over his badge. Before talking, he paused to compose himself.

“We’re hurting,” he began. “All I know is this must stop. This divisiveness between our police and our citizens.” He explained what happened the night before, so tired that he had to stop and carefully enunciate the words “bomb robot.” He complimented all the officers involved and related some of the things Johnson had said the night before. “The suspect said he was upset at white people. The suspect stated he wanted to kill white people, especially white officers.” He closed by calling the Dallas officers and transit officers “some of the bravest men and women you’d ever want to be associated with.”

At another press briefing a few days later, while giving an update on the investigation, he spoke to reporters and newscasters gathered there about the larger issues facing police. “We’re asking cops to do too much in this country,” he said. “Every societal failure, we put it off on the cops to solve. Not enough mental health funding? Let the cops handle it. Not enough drug addiction funding? Let’s give it to the cops. Here in Dallas, we’ve got a loose-dog problem. Let’s have cops chase loose dogs. Schools fail, give it to the cops.” It’s too much to ask, he said. “Policing was never meant to solve all those problems.”

He said police need help from other parts of our democracy, including the free press. And he spoke directly to protesters. “We’re hiring,” he said. “Get off that protest line and put an application in. We’ll put you in your neighborhood, and we’ll help you resolve some of the problems you’re protesting about.”

Here, addressing America directly, was a black police officer. Someone who knew both the pain of losing officers in the line of duty and losing a son at the hands of officers. Someone who had worked hard to reform policing, to lower violent encounters. Video of that press conference was shared millions of times because, even during this terrible time, Chief Brown was a symbol of hope.

His life is proof that you can support the men and women who serve and protect us and still want cops who violate the public trust to go to jail—or at least lose the badge. You can believe that people should respect and cooperate with police officers, but that not doing so shouldn’t result in death. That people in general should have more empathy and compassion for one another.

“He just goes about his life,” says Mayor Rawlings. “But his sense of grasping reality and facing it and looking it in the eye is really kind of off the charts.”

On July 12 there was a large memorial downtown. There were speeches from President Obama, from former President George W. Bush, and from the mayor. But it was the chief who offered perhaps the most genuine, emotional remarks.

“When I was a teenager and started liking girls, I could never find the right words to express myself,” he said. There were snickers across the room. “Being a music fan of seventies rhythm and blues love songs, I put together a strategy to recite the lyrics to get a date.” There was more laughter from people in the theater: young, old, white, black, police officers, politicians, regular people who just cared enough to show up. Brown explained that if he liked a girl, he might recite some Al Green or Teddy Pendergrass or Isley Brothers. “But if I fell in love with a girl, I had to reach down deep and get some Stevie Wonder.” Today, he said, he wanted to pull out some Stevie Wonder for the families of the fallen officers—and for the officers themselves. He told the crowd to close their eyes and imagine they were back in the seventies.

“We all know sometimes life’s hates and troubles can make you wish you were born in another time and place,” he recited. “But you can bet your lifetimes that and twice its double that God knew exactly where he wanted you to be placed.”

The officers who had been laughing a moment earlier began to cry. The politicians too. And as Brown went on, reciting lyrics, the grief came pouring out.

“Until the rainbow burns the stars out of the sky, I’ll be loving you. Until the ocean covers every mountain high, I’ll be loving you.” He went on. “Until Mother Nature says her work is through, I’ll be loving you. Until the day that you are me and I am you—now ain’t that loving you.”

After unthinkable tragedy, this is what he had for the city and the country. He had love.

A few months after the shooting, Brown decided to retire from the force. He says that before the attack, when it felt like the whole world was calling for his ouster, he knew that 2016 would likely be his “final lap.” He expected he’d get fired for his community-policing policies, and that seemed like a noble cause to sacrifice for.

Instead, he was the grand marshal of the St. Patrick’s Day parade, always the biggest party of the year in Dallas. Tens of thousands of people lined both sides of Greenville Avenue for the parade, and tens of thousands more packed themselves into nearby bars and house parties. The crowd was as diverse as the city itself: rich and poor, young and old, people of all races and religions celebrating side by side on a sunny Saturday afternoon.

Despite the presence of uniformed police officers in every direction, most people were also drinking openly. A few of the more brazen were smoking weed. That’s because this is the one day of the year when Dallas—or at least this corridor of Greenville—feels more like Bourbon Street. It’s the one day when the police officers don’t worry about open containers or public intoxication because, well, the community doesn’t want them to.

There were drummers and bagpipers marching and music playing on every street corner. Parade participants tossed green beads to the crowds and the spectators threw stale marshmallows and green tortillas. Neighborhood parties spilled out onto the sidewalks and tailgating groups blended together around coolers and kegs.

Brown was decked out in a slick navy blue suit, with a Kelly green top hat, a matching green tie, and old-school green Adidas sneakers, and he perched on top of the backseat of a new Rolls Royce convertible as it moved slowly down Greenville.

Brown smiled and waved to both sides of the street. At first he seemed a little reserved and stiff, uncomfortable with this sort of attention. But soon he was lifting his top hat, extending his arms with a flair of showmanship. He lifted his right foot so the crowd could see his green sneakers. He pointed to a young man who was wearing nothing but green bikini briefs and yelled to him, “Nice shorts, brother!”

To his credit, he’s remarkably candid about why he stepped down. He knew his popularity was at an all-time high, that he’d served his purpose on the force. “A police chief can’t be untouchable,” he says. Even his harshest critics—the few that remain, anyway—had used that word to describe Brown before he retired: untouchable. Everyone else, from protesters to presidents, has been hailing him as a voice of unity.

“Chief Brown was a really strong leader, not just of the Dallas Police Department but of our community,” former President Bush told me recently. “He cared deeply about every part of our city, every neighborhood. He was a unifying figure throughout his tenure and an example of strength and grace when he was needed most.”

Brown’s book will be released on June 6. He’s also taken jobs at a private security company and at ABC News, where he is expected to comment on topics ranging from race and policing to mental illness and guns. He says Dallas will always be his home, even if he has to live somewhere else for work.

He’s never been overseas, so he plans to travel to Europe and Asia. He doesn’t remember the last vacation that wasn’t cut short by work; eventually he quit trying to travel and just stayed in town. He also plans to play more golf. Most immediately, though, he’s had to teach himself how to drive like a civilian again. He says he hasn’t looked at a speedometer or searched for parking in more than thirty years.

A lot of people are hoping he might enter politics; actor Tom Selleck said he wrote in Brown’s name on his presidential ballot last November. Brown concedes he’s always been ambitious. And a lot of political careers begin with books that have titles like Called to Rise. Brown says he’s just happy to feel appreciated.

“Have you ever been in a relationship where you love someone and they didn’t love you back?” he asks. “That’s how you feel in this profession. But after July 7, they finally love me back.”

Near the end of the parade route, Brown was still tossing beads, pointing at the cheering crowd. As the car slowed for the final stretch, a tall white man wearing a kilt and no shirt burst through the line of onlookers and out into the street. He seemed less than sober. He ran over to Brown, who was still perched at the top of the backseat.

“I just want to thank you,” the man said. He was out of breath, and a little drunk, but he seemed to be having an emotional experience. He looked up at Brown. “Thank you for saving the city,” he said. Then he shook the chief’s hand and wandered back to his friends.

When the Rolls Royce came to the end of the route, Brown got out. He thanked the driver and the staff. Then he headed to his car, parked nearby. The parade was still going on behind him. He could hear the drums and the bagpipes and the drunken masses. It had been fun, but he had finished what he came here to do, and now it was time to go.

Michael J. Mooney lives in Dallas and is the author of The Life and Legend of Chris Kyle.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Police

- Longreads

- Black Lives Matter

- Dallas