This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

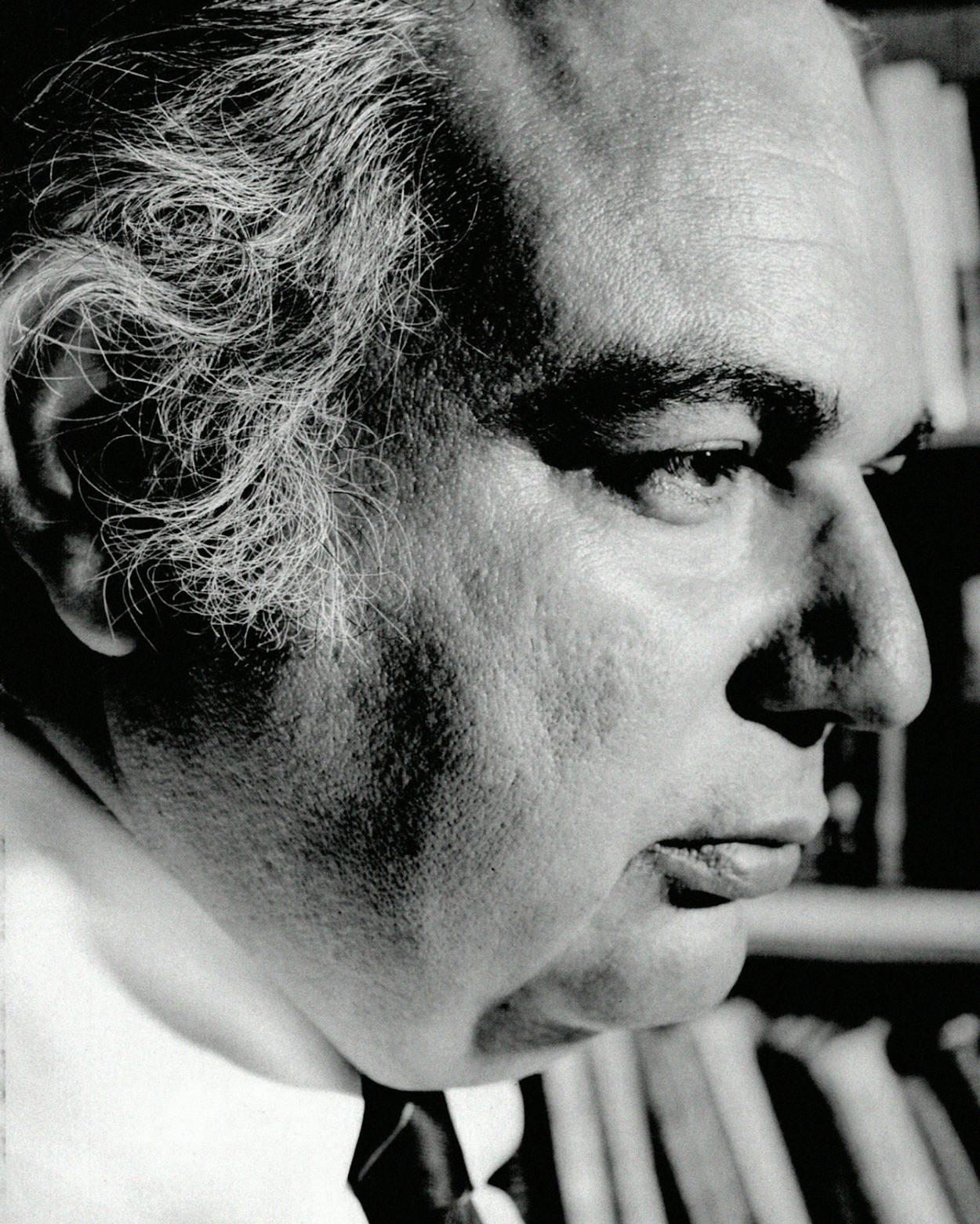

The man standing in front of the classroom didn’t look like one of the most powerful people in Texas. For one thing, he was Hispanic or, as Ernesto Cortes, Jr., likes to call himself, Mexican. A short, barrel-shaped, almost volcanically intense man of 48, he looked like a Mexican sumo wrestler, a cold glower of anger frozen across his dark face. The glower was mostly for effect, though the students at a ten-day national leadership training conference on South Padre Island hadn’t yet figured that out.

Suddenly, for no apparent reason, he turned to a blond woman from Minnesota and snapped, “Get out! ” She looked at him blankly. “Get out of the room,” Cortes repeated. A few minutes later he ordered another student out, then a third. All three left promptly, sneaking sheepish looks back as they closed the door behind them. Inside the room, the silence was supercharged. Some of the students were angry, others near tears, all of them confused and wondering what the hell was happening.

What was happening? Ernie Cortes was playing one of his mind games, the better to demonstrate a point—in this case, that the unquestioning acquiescence to authority robs us of our dignity and rights. After several awkward minutes another student—a Lutheran minister from Fort Worth named Terry Boggs, who had apparently figured out the purpose of the demonstration—took it upon himself to invite the three back inside. This did not please Ernie Cortes, who flashed his icy glare at Boggs and barked, “Do you know what you’ve just done, Terry? You’ve violated the iron rule! Never do for people what they can do for themselves.”

Ernie Cortes knows all about the iron rule. It is his own perpetual nemesis as a community organizer whose job is to teach the poor how to attain and exercise political power. Fame is the kiss of death for an organizer. It deflects the spotlight away from the organization and onto the person at the top, with potentially disastrous results for both. Cortes is trying hard—well, pretty hard—not to be a celebrity. But he has been so successful at his work, ever since he founded San Antonio’s Communities Organized for Public Service (COPS) two decades ago, that he has become the unofficial spokesman for Texas’ poor. Today, as the Southwest regional director of the Texas Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), he oversees a loose network of eleven organizations in Texas and others stretching all the way to Arizona. Such unlikely bedfellows as Ann Richards, Bob Bullock, Ross Perot, and Tom Luce regard Cortes not just as a friend but as a modern hero. Any informed list of the most powerful Texans would include Cortes for the simple reason that he—or, as he would prefer to put it, the IAF network—has changed Texas politics by giving have-nots a place at the bargaining table.

Cortes has been called a radical, an agitator—a Dutch priest in San Antonio who hated his guts called Cortes an activist, the dirtiest word he could think of—and Ernie is all of those things. But what he really is is a teacher. He teaches empowerment. He teaches people to think and act for themselves, to challenge authority, to speak up for their own self-interest. Power comes in two forms, he told the students on South Padre Island: organized people and organized money. Since most of the IAF’s grass-roots organizations are, at least in the beginning, dependent on the financial support of churches in poor areas, their real wealth is people.

The students were mostly pastors, church lay leaders, and social workers, their ages ranging from early twenties to seventies. They had come to South Padre Island from all over the country and even from overseas, some at great personal expense, to attend the conference. The students were card-carrying liberals every one, and they were expecting to have their do-gooder consciences raised. Instead, their consciences were being assaulted. They had grown up believing that the meek would inherit the earth. Now they were hearing that the meek were patsies. Later in the course they would be required to read a scholarly essay titled “On the Importance of Being Unprincipled.” They were instructed to look at the world not as they wished it to be but as it was. In this scheme of things, the concepts to be courted and desired—the students found it difficult even saying the words—were power and self-interest.

For one lesson Ernie had his students read a chapter from Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, dealing with a debate between the mighty Athenians and the powerless but defiant citizens of the island of Melos. Then the students role-played the debate, alternately taking the parts of the Athenians and the Melians. At first, everyone in the class identified with the underdog Melians. The debate seemed to be no debate at all but an uncompromising demand by the Athenians that the Melians surrender, submit themselves to slavery, and pay tribute. In return, the Athenians promised not to destroy them. The Melians said thanks but no thanks and were subsequently slaughtered and enslaved.

Role-playing the two sides, the students began to see subtle variables. Though the Athenian language was blunt, concrete, and specific—the language of the powerful—it was also rich with nuances. The Melians, on the other hand, spoke the language of the powerless—abstract, idealistic, and inflexible—with them the question was either-or. Ernie wanted the class to understand that no matter how bleak things appeared, it was in the Melians’ self-interest to pursue a deal.

“You can’t always appeal to hope and justice,” he told the class. ”You have to put yourself into a negotiating position.”

“What about integrity?” asked an Anglican priest named G. Foster, who had traveled all the way from Wales and was wondering if he had made a terrible mistake.

“Integrity!” Ernie said mockingly, making the word sound profane. He bent down until his face was only a few inches from the face of the Anglican priest: “Abraham Lincoln, perhaps our greatest president, once said, ‘I would like to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.’ ”

“But you can’t just toss aside your principles,” observed Mike Breslin, a Roman Catholic priest from Brooklyn who had left the priesthood to get married.

“Some people are congenitally over-principled,” Ernie replied. ”Only lunatics and dictators can afford to be overprincipled.”

“But is survival really the most important thing?” asked Peter Sims, a Presbyterian minister from Philadelphia.

“I’m not talking about personal survival,” Ernie said. ”Remember the lesson of Abraham? Because Abraham survived, his people survived. The Melians committed the ultimate act of stupidity—they failed to survive.”

By the end of the day, on the question of whom they most admired, at least a third of the students had changed their minds. “I’m still a Melian most of the time,” said Prenessa Seele, an AIDS counselor from Harlem. “But I want to be an Athenian.”

There was always an undercurrent of humor in Ernie’s teaching style, even as he was agitating and challenging. “When you go out into your neighborhoods and parishes to recruit new leaders,” he told his class, “look for people whose sense of outrage is tempered by humor. Never trust a revolutionary who can’t laugh at himself.”

Pacing the room, rolling his short arms like a boxer warming up, tugging at his baggy Sansabelt britches, Ernie looked a little like Danny DeVito. He had the timing and range of a great comedian and an orator’s command of language. He used his body the way an athlete uses his strength, making himself appear top-heavy and graceful at the same time. Telling war stories of life on the IAF front, he acted out the role of each combatant: Now he was Bill Clements, his voice mean and dripping with malice, his eyes mere slits; now he was Henry Cisneros, his incredulous voice pleading for understanding, his eyes wide as silver dollars. Every move was measured and confident. Even when he turned his back to the class and appeared to be searching for his next thought, every set of eyes followed and waited, as he knew they would.

The war story that most would remember was from his early days when he was organizing COPS in the mostly Hispanic neighborhoods of San Antonio, his hometown. The year was 1974, and some city officials snubbed COPS when it proposed a counter-budget during budget negotiations. In a now-famous exercise in guerrilla theater (the IAF refers to these confrontations as actions), Ernie led hundreds of Hispanics downtown to two of the city’s most venerable establishments. With TV cameras recording the chaos, COPS members tried on garments (but, of course, didn’t buy them) at Joske’s while others jammed the lobby of Frost National Bank, changing their dollars into pennies and back into dollars again. After that action, everybody in San Antonio had heard of COPS.

An action, Ernie told the students, is to the organization as oxygen is to the body: a group doesn’t exist to stage actions, but it stages actions to exist. That aphorism would become clearer in a few days when the students got to see an action up close. Governor Ann Richards, who had been in office only about a month, had agreed to meet face-to-face with the leaders of the Texas IAF network and its local affiliate, Valley Interfaith, at a rally at the International Convention Center in Brownsville. The success—or lack of it—of that action would go far in determining how the Texas IAF network fared for the next four years.

An economist by training, Ernie Cortes is gifted with a superior intellect and an ego sufficient to exercise it. His role model is Moses, whom he considers the greatest organizer of all. “Moses took the burden that God had given him and placed it on the people,” he says. “That’s basically what an organizer does—finds the people who are going to actually do the organizing.”

In addition to overseeing the Southwest for the IAF, which he does from Austin, Ernie also has his eye on Mexico and plans to spend several weeks in September working with organizers in Liverpool, England. Since local groups are basically autonomous, Ernie’s job is to train and advise his lead organizers, assign them to various local organizations, and bring them together to work on state issues. At Ernie’s insistence, lead organizers are summoned to monthly seminars to listen to (and argue with) experts in subjects ranging from labor relations to theology; leaders must also read biographies of such diverse exponents of power as Disraeli, Churchill, Huey Long, Martin Luther King, Jr., even J. Edgar Hoover. Ernie refers to such apparently gratuitous scholarship as “building intellectual capital.”

Ernie doesn’t drink, smoke, or indulge in small talk. He can and does debate theology, history, philosophy, and literature with scholars. He has committed passages of Shakespeare and Shaw to memory, loves the theater and concerts—and can whistle parts of the Brandenburg Concertos. In interviews, depending on the topic, he is likely to quote Jefferson, Freud, and Tocqueville; Aristotle, Kant, and Faulkner; Paul’s letters to the Corinthians and snatches of dialogue from the movie Viva Zapata! His idea of a relaxing conversation is a slam-bang debate with his longtime friend and early mentor Lou Stern on, among other favored subjects, economic man in medieval society. Stern, who is now on the faculty at the University of Houston, was Ernie’s economics professor at Texas A&M and sits in as an unofficial adviser when Cortes meets with his lead organizers.

Cortes is a prodigious reader of books, newspapers, and magazines (and a writer of long-winded tracts on subjects like job training and education reform), and he can’t resist challenging the intellect of people he meets, especially if they are wielders of power. “The first thing Ernie asks,” says Tom Luce, “is, ‘What books are you reading?’ ” Heaven help the friend of Ernie Cortes who runs into him in a bookstore; one victim ended up buying, at Ernie’s direction, works on Dien Bien Phu, Frederick the Great, and feminist criticism. Cortes usually has a book bag over one shoulder. The hallway of his small office at Texas IAF headquarters in Austin is so clogged with books that a visitor has to turn sideways to pass.

As a child Ernie read the encyclopedia and the Bible for recreation. Even today his style is to pounce on some arcane subject and binge. During national training in February, a time when his daughter Ami was studying the Reformation at the University of Texas, Cortes kept on the nightstand of his hotel room a book on the Reformation, a biography of John Calvin, and two volumes on the history of church thought from 1300 to 1700—in case Ami called and wanted to talk shop. When I saw Ernie five months later in Austin, he was reading Myth and Society in Ancient Greece, The Conquest of Politics, The Black Church and the African American Experience, Essays in Experimental Logic, a history of Yugoslavia, and a biography of Cardinal Richelieu.

Beyond all of his intellectual posturing, Ernie is at root an ascetic Catholic in the tradition of Thomas Merton, Dorothy Day, and other stern modern-day Catholic liberals. The Roman Catholic images he grew up with as a boy—angels and demons, a beatific madonna, the wounds of Christ—still form the terrain of his mental landscape. “To spend time with Ernie,” says a friend, “is to remember the passage from Matthew in which Jesus warned his disciples, ‘I came not to send peace but a sword.’ ” Ernie has the classical view of religion: Its purpose is not to bring inner peace but to challenge. Like Jesus, he is a man who can’t sit still for peace. In his mind, the real work of the prophet is to set up an ethical system so lofty that no one can possibly reach it and then spend the rest of his life striving for ethical perfection.

Most of all, Ernie believes in politics—that is, he believes in the political process, a belief that goes back to his boyhood. Ernie’s uncle, who started the first Mexican television station in San Antonio (Channel 41), was involved in Adlai Stevenson’s campaign. All of Ernie’s family supported Henry B. Gonzalez’s rise in politics from state senator to congressman. A sign proclaiming “Send Henry B. to D.C.” seemed to be a permanent fixture in his grandfather’s front yard.

The ideology that drives Ernie Cortes does not fit comfortably into a category, which helps explain his broad base of support. “Henry B. used to call himself a consiberal,” Cortes says. ”Maybe that’s what I am.” Although his job is helping poor people, and although in American politics that is traditionally the concern of liberals, Ernie is not tainted with liberalism.

Why not?

For one thing, he—like the organization he has built—is nonpartisan, nonideological, and nonpersonal; that is, he doesn’t believe in the cult of the individual politician. For another, he doesn’t spout the usual liberal agendas of civil rights, curbing police brutality, affirmative action, more regulation of business, concern for the homeless—not because he doesn’t think these are problems, but for two other reasons.

First, these issues may concern interest groups, but they don’t inflame ordinary people. “When we meet with ordinary people in their homes,” he says, “they are more concerned with crime in the neighborhood and the safety and education of their kids, than they are with police brutality.” The issues that people will organize around are not intellectual ideas but things that can change their lives. Second, it is crucial to the concept of organizing to have victories, to show improvement. It is hard to show the tangible results of campaigning against police brutality or for civil rights and extremely difficult, even if you can show results, to relate any advances to the lives of ordinary people. A new storm sewer or a paved street is an advance that can be measured, as is an air-conditioned school or a health clinic. The result of Cortes’ pragmatic approach is that he takes people who feel that they have no stake in politics and makes them a part of the system.

One of Ernie’s favorite books is In Defense of Politics, by English political theorist Bernard Crick. The point of the book is that the essence of politics is compromise. Saul Alinsky, the founder of the IAF, preached the same message: “The definition of democracy is compromise.” Compromise is not just something to be tolerated or a necessity, it is something to be praised and ardently courted. Ernie tells brokers of power: There are things we want, things we have earned; they are good public policy, and it is in your interest to give them to us. His goal is to teach people how to get to the bargaining table. The way politics works is that once you are there, you get something. The only people who get shut out are those who aren’t there.

It is this willingness—this eagerness—to compromise that appeals to conservatives like Luce and Perot. Ernie doesn’t teach people how to take over; he teaches them how to participate. Most power brokers see politics as exclusive; Ernie sees it as inclusive.

“Understand this,” he says. “There is a vast difference between a healthy, negotiated compromise—a Rooseveltian bargain where everyone gets something—and a negotiation where one side has an inordinate amount of power and the other side has to accommodate itself to that power. I don’t believe anyone should have too much power. I believe that power should be accountable, which is a classically liberal position. But I’m a conservative in that I believe in family, neighborhoods, tradition, church, faith, hard work—those things are important to me. And I’m a radical about justice.”

Another reason that conservatives like Cortes is that he doesn’t care whether a politician is black or white or Hispanic: He cares only whether that politician is for him or against him. When Henry Cisneros moaned that the constant demands of COPS were making him literally ill, Cortes had a woman dressed as a nurse sit next to Cisneros at the next negotiating session.

Except that he has a sense of humor, Ernie is the political equivalent of a religious fundamentalist, trying to bring politics away from humanistic moralizing and back to its basic purpose of saving the civic soul. How good are the schools in our neighborhoods? How safe are our streets? How well do our streets drain? How bad is the traffic? How can people get jobs and access to health care? If these questions are addressed, the rest will eventually take care of itself.

“Ernie is interested in results,” says Tom Luce. “A lot of people talk about problems, but Ernie proposes solutions.” Luce appears to genuinely like Cortes. So does Ross Perot. “Anybody who is interested in issues like sewers and curbs has got to have a good soul,” says Perot. Thoughtful conservatives such as Luce and Perot share with Cortes a distaste for the eighties because it was the age of short-term gratification, not just for business but also for politicians, who don’t seem to be as interested in solving problems as in being on TV and getting campaign contributions. They are interested in the same things, Ernie Cortes and these two conservatives: long-term solutions, stabilizing institutions such as neighborhoods and families, and organizing the country in a way that lets people with ambition and talent, be they rich or poor, get ahead.

The demons that drive Ernie Cortes rise from his boyhood on San Antonio’s impoverished West Side. Ernie’s family started out poor but gradually became fairly well-off by community standards: His father and other relatives owned an entire block on Bonita Street. Many of the homes on the West Side were owned by absentee landlords who considered indoor plumbing a luxury. Many of the streets were unpaved and without storm sewers. When the rains came, creeks flooded and children drowned. The air was putrid with the stench of stockyards and rendering plants, and rat- and mosquito-infested junkyards sprouted next door to homes and churches. Complaints to city hall went unanswered. Nobody seemed to care what happened to the West Side, at least nobody important. Ernie’s younger sister was born brain-damaged and died as much from society’s indifference as from her own frailty.

Racism was something he felt in his bones. His mother and father had once left a restaurant without finishing their meal, not because of words overtly spoken but because they had heard people hissing behind their backs. To Ernie Cortes the Alamo didn’t represent the cradle of Texas independence. Instead it was a symbol of his people’s ongoing humiliation.

Still, he was hardly a radical by the time he graduated from San Antonio’s Central Catholic High School and enrolled at Texas A&M in 1960. Lou Stern, his economics professor, remembers him as “a typical cadet—Corps happy, starched khakis, burr haircut, the whole works.” Ernie remembers that on the eve of graduation he felt cheated, as though his education had prepared him to do nothing meaningful or useful. He drifted into graduate school at UT-Austin and waited for inspiration to strike.

The death of his father in 1966 was a landmark event in Ernie’s life. Ernesto Cortes, Sr., had worked many years for a soft-drink bottling company, believing that in his old age the company would take care of him. “He didn’t understand that he had to live to collect the pension,” Ernie says. “He had always told my mother that she would be taken care of, that he was worth more money dead than alive. Then suddenly he was dead, and there was no money. She would sit up late at night, trying to read these insurance policies and legal papers, totally bewildered.”

Ernie quit graduate school and took a full-time job with the United Farm Workers, sending his mother half of his modest salary. He worked for a black church in Beaumont and in several difficult political campaigns, looking for something he couldn’t describe, struggling with a growing frustration that politics didn’t go deep enough. “There were no discussions—no engagement,” he remembers. “School board elections had very little to do with how schools were run. Politicians weren’t connecting to people’s private pain.” A lot of thoughts were churning in Ernie’s head. He knew that he wanted to be an organizer, but he wasn’t sure what to organize or where. He worked for a time as an economic development specialist for the Mexican-American Unity Council, launching, among other projects, the first Mexican-owned McDonald’s franchise in the country. The franchise was owned partly by the council and partly by a former gas station operator the council recruited. Ernie’s dream was that the community would eventually buy shares of stock in the franchise and that profits would allow the council to organize the community. But it never happened. “I began to hate the work, hate myself,” he says. “It had become a task—finance, management, cash flow, things I was not exactly enamored by. At the same time I began to realize that the council couldn’t do what I wanted to do—build a constituency.”

Cortes knew a little about the Industrial Areas Foundation from talking to friends in the civil rights movement and in the farm workers union. He had read a chapter about the IAF in Saul Alinsky’s biography of labor leader John L. Lewis. A series in Harper’s had featured the organization, and he had read Alinsky’s best-selling book Reveille for Radicals. Alinksy was no idealist or social dreamer; he was a hard-core radical who wrote extensively about how to overcome the weaknesses of the poor by exploiting those of the rich and powerful. What Cortes really wanted to do, he began to realize, was study at the IAF Training Institute in Chicago, then return home and shake San Antonio by its heels. At almost the same moment that he decided the way to bring about change in San Antonio was to abandon electoral politics for something more radical, another alumnus of both Central Catholic High School and Texas A&M named Henry Cisneros was reaching the opposite conclusion.

In 1971 Cortes enrolled in a ten-day course at the IAF Training Institute. Ed Chambers, the founder of the institute, recalls his first impression of Ernie Cortes: “Disheveled and disorganized, books under both arms, no coat, no tie . . . people said he looked like a pachuco.” Cortes wanted Chambers to teach him how to organize San Antonio, but Chambers shook his head and told Cortes to forget it. A large, gruff man who looked as if he would enjoy breaking jaws for a living, Chambers saw enough raw potential in Ernie Cortes to cut a deal. If Cortes would spend eighteen months organizing in East Chicago, Chambers would be his mentor for a similar undertaking in San Antonio. “The mistakes he made in Chicago were the mistakes he would have made in San Antonio,” says Chambers. “He had to learn to organize on his own or else he wouldn’t have had the ego to organize in his hometown.”

As Cortes began to complete his work in Chicago, Chambers allowed him to make progressively longer trips to San Antonio to stir up community support for an IAF organization and to build a constituency. Cortes came back and gave Chambers his version of a power analysis of San Antonio. On a long sheet of butcher paper Cortes listed the names of judges, labor leaders, congressmen, and political party chiefs. Chambers looked at it coolly and asked how Cortes happened to overlook the most important power group of all, the local churches.

“You could almost see a light bulb go off in his head,” Chambers said. ”Ernie’s background was economics and electoral politics. I had to teach him that the greatest potential resides in the institutions that people are loyal to and pay their money to and are willing to sacrifice for—the church, the family, and the schools.”

Cortes’ group, Communities Organized for Public Service, became a model for future IAF organizations. COPS took no federal or government money, hustled no foundation or corporate grants, aligned itself with no movements, and backed no political parties or candidates—though it promised to make life miserable for any candidate who opposed its goals. IAF organizations hold what they call candidate accountability sessions. In a forum reminiscent of the Inquisition, candidates are seated in hard chairs in the center of the room and asked if they agree with a list of specific IAF proposals. Only yes or no answers are accepted.

Ernie Cortes knew that the toughest part of the battle would be beating back the myth that San Antonio’s Mexican Americans had accepted for years—that the city in its wisdom would take care of them someday, somehow. To find his core group of leaders, Ernie interviewed more than a thousand people, many of whom were appalled at the idea of activism. Seventeen telephone calls were required to set up a meeting with Beatrice Gallego, a PTA leader and housewife whose daughter had won a Miss Teenage San Antonio contest. Gallego had heard all this before, young Chicano hotheads talking about storming city hall and changing the system.

When Ernie asked Gallego about problems in her neighborhood, she began to laugh. “What’s not a problem?” she said. “We have no drains, no sidewalks, no curbs, no parks, we’re cut in half by an expressway, we don’t have enough water pressure to water our yards and draw bathwater at the same time.”

The leaders Cortes recruited—people like Gallego and David García, a young deacon at Immaculate Conception in a neighborhood near the stockyards called La Tripa (the Guts)—weren’t activists or extremists or party loyalists; they were people who had organized church and PTA festivals, baseball tournaments, Boy Scout troops. Many had never thought of themselves as leaders or organizers much less as people who might stand up at city hall and speak out. But at parish meetings Ernie began to challenge and agitate, playing on their latent anger and sense of injustice, showing how the system worked against them. In the course of searching public records, the new leaders discovered to their amazement that funds targeted in bond elections for West Side projects had been systematically diverted to the wealthy North Side.

“Ernie taught us to take a look at the whole power elite,” says Father García, who is now the archdiocesan vocation director. “How were decisions made in city government? Who set utility rates? Who decided which schools got their roofs repaired? Who got the money that resulted from these public decisions? He taught us to analyze the situation in ways that affected us personally. I was twenty-four at the time, and he was concerned with my growth as a priest. He was always challenging me, wanting to know what I was reading. I learned a lot about what it means to be a pastor from my association with Ernie.”

In August 1974, not long after COPS members jammed the lobby at Frost National Bank and the aisles at Joske’s, Ernie asked for and was granted a place on the city council agenda. At this point he faded into the background, kibitzing, prodding, and evaluating, but allowing his trainees to take charge. The membership selected as its spokeswoman Mrs. Hector Aleman, who lived in a neighborhood near Holy Family Catholic Church that flooded with every hard rain. When Aleman rose to speak at the council meeting, so did the entire COPS delegation. For the first few seconds her voice trembled, but it grew louder and angrier as she warmed to her subject. “How would you feel,” she shouted to the startled members of the council, “getting out of bed in the morning and stepping into a river right in your house?”

In the seventeen years since its founding, COPS has won more than $750 million in new streets, drainage, parks, libraries, and other services in its neighborhoods. Henry Cisneros, who has clashed with Cortes over numerous issues, nevertheless credits COPS with altering the moral tone and the political and physical face of the city. And as mayor, Cisneros learned that he could use COPS to keep a rein on the corporate community. Back off, Cisneros would say, in effect, or I’ll sic the bomb-throwers on you.

COPS today is an accepted part of the political process in San Antonio. The organization shaped the debate during the 1991 mayoral race by unveiling its new jobs training proposal and demanding at an accountability session that the candidates support or oppose it. The plan asks business and corporate leaders to identify specific jobs expected to be available in two or three years, then provides a program to train young people to fill those jobs. Almost everyone agrees that this is a great concept—Ross Perot calls it “as sound as the dollar used to be”—but there is still the matter of appropriating about $30 million for three years for the pilot project. And while the jobs concept is far more ambitious than the drains and streets that occupied COPS members in the early years, the bottom line is the same—keeping COPS in the forefront of making life better for ordinary people.

Ernie Cortes keeps trying to stay in the background and to respect the iron rule of organizing. He knows all too well what happened to Saul Alinsky, the founder of the IAF. The apostle of community organizers ended his days giving speeches and interviews, but after the mid-sixties nobody took him seriously as an organizer. Ernie is learning the same hard lesson, that fame is a temptation not easily avoided, and once it has you in its clutches there is no salvation.

In 1984 the MacArthur Foundation recognized Cortes’ work with a $204,000 no-strings-attached “genius” grant. That’s about four years’ salary for a top-flight organizer. In the last year Cortes has been the subject of a book, Cold Anger, by Mary Beth Rogers, Ann Richards’ chief of staff, and has been profiled by Bill Moyers as part of Moyers’ A World of Ideas series on public television. When a man is as accepted in the halls of power as Ernie Cortes is, he is perilously close to becoming a household name.

In the early days of COPS, Cortes reminded his leaders several times, “Hey, this is not about some Mexicans getting some power. This concept is bigger than that.” Cortes himself was reminded of that lesson in 1976, when Ed Chambers summoned Ernie and told him that it was time to leave San Antonio. Chambers had prepped a new territory in East L.A. for Cortes to organize. Ernie was stunned. San Antonio was his home. He had just married his second wife, Oralia, and they were beginning to raise a family. In his two and a half years of organizing, COPS had become successful beyond his wildest dreams. Now his boss wanted him to give it all up and move to Los Angeles. To Ernie’s credit, he agreed.

“If he had stayed,” Chambers says, “he would have destroyed COPS and smothered himself. He had done as much as he could for those leaders. He would have stopped being an organizer and become the leader.” As if to emphasize his point, Chambers replaced Cortes with Arnie Graf, a Jewish organizer from Milwaukee who didn’t speak a word of Spanish.

Ernie went on to new successes in Los Angeles, Houston, El Paso, and other places, following the pattern laid down by COPS, identifying and training organizers and leaders, who then carried on the bulk of the work. Just as Chambers was a mentor to him, Ernie Cortes made himself a mentor to many of his top organizers. Sister Christine Stephens, now second in command of the Texas IAF network, was president of the Metropolitan Organization (TMO) in Houston when Ernie took over TMO in 1978. She was recruited not just for her organizing ability but for her short temper. “They valued the fact that I could vent my anger,” she says modestly. Though she had been in her San Antonio–based teaching order for sixteen years, Stephens had no idea what direction her ministry would take.

“I was very suspicious of the IAF—all that open advocation of power, all those rough, tough-talking men,” she recalls. “There were no women organizers back then. What impressed me about Ernie was that he took religion very seriously. He had a biblical vision of justice, of how things ought to be and could be. I was always very nervous talking in public, but Ernie sat me down one night and talked about what it meant to be a public person, how your true self is just over your shoulder where you can’t see it, and how the only way you can know yourself is to see it reflected in someone else. No one had ever talked to me like that before. I realized that I had to grow, develop, take risks, that that’s what I had entered the convent to do. And Ernie was there all the way, agitating, challenging.”

Most recently Cortes transferred Stephens from the Valley to Dallas. He needed her to organize a new group called Dallas Interfaith, but the move was also part of the IAF discipline. Stephens was in danger of becoming too charismatic in the eyes of her followers.

The other part of Cortes’ job is to supervise statewide agendas and make sure that the IAF is a living presence in the state capitol. It is the way of the Capitol to identify groups by their lobbyist, and Cortes is thought of as a lobbyist for the organized poor. In an arena in which perception is everything, Cortes exercises substantial clout.

The organization began making inroads in Austin right after the 1982 elections, when Mark White came to a COPS convention and began to hear that education reform involved more than raising teachers’ salaries. “We taught him about equalization,” Ernie recalls. The next year White asked whether the IAF wanted a representative on a newly formed education committee, chaired by Perot. No, Ernie said. All the IAF wanted was access to the committee. Cortes and a delegation from the Texas IAF persuaded Perot to meet with members of Valley Interfaith, the new IAF group in South Texas. Perot’s presence gave Valley Interfaith what it desperately needed—recognition—and the rally, which drew more than two thousand mostly poor Hispanics, impressed on Perot how committed they were to improving education. “The highlight of the evening,” Cortes recalls, “was when one teacher stood up and described how four different classes of students had to share a single tiny classroom, with four teachers talking at once.” Prodded by such dramatic demonstrations, the Perot committee made recommendations that led to more than $1 billion being spent to help property-poor districts.

In 1985 the Texas IAF network scored another major victory with the passage of a law to provide indigent health care. Four years later the IAF helped push through laws to provide sewer and water to colonias in South Texas. But when Bill Clements left office fourteen months later, the colonias still didn’t have sewers and water.

The plight of the colonias was at the top of the agenda in February when Ann Richards appeared before members of Valley Interfaith and students from the IAF training conference at the International Convention Center in Brownsville. Valley church parishes bused in so many people (estimate: 2,500) that the IAF floor managers couldn’t always control them. While mariachis blared in the background, Richards walked through the crowd on her way to the stage, people reaching around her escort of DPS troopers to touch her, as if to satisfy themselves that she was real. Many were residents of the colonias and spoke no English. Seeing them there in their Sunday best with their children and grandchildren, one was struck by their sense of dignity and their latent power. What was hard to grasp was the extent of their poverty and the degrees by which it affected all of their lives. Margaret Horbovetz, for example, was regional cochair of Valley Interfaith and had worked for three years to get water to the colonias. Horbovetz lived with her husband in a small house on the highway between Alamo and Donna, and, ironically, they didn’t have water either. They paid a driller $2,000 to strike salt water.

As Horbovetz and others walked to the microphone and delivered their demands to the governor, Ernie prowled the back edges of the crowd like a nervous producer on opening night. Ernie Cortes and Ann Richards went back 25 years, to the days of the UFW melon boycott. They had been an impressive team, Ernie and Ann. She would dress up like the North Dallas housewife that she was and engage a grocery store manager in conversation while Ernie waited in ambush behind a stack of melons, ready to deliver his message that melons—these particular melons, anyway—were the product of the devil. But the days of Ernie and Ann ended when she was elected governor, at least for Ernie. Now she was Governor Richards, not an enemy but, like all politicians, an adversary. At a pre-rally briefing for the students in national training, Sister Christine Stephens explained, “The governor is basically a good ol’ boy politician who likes to erase the boundaries. What we’re trying to do today is reestablish that boundary.”

Ernie had reason to be nervous: The action had been successful, but it lacked confrontation and drama. The extravaganza at the convention center was mostly for show—the issues had been negotiated and agreed on in a series of private meetings between Richards’ staff and the IAF leadership—but for the action to be a total success it needed a sense of drama, and that wasn’t happening. One after another, IAF spokespersons made their demands—for job training, for health care, for education, for improving the colonias—and before they could return to their seats, the governor said yes. Yes, yes, yes, yes. There was a wonderfully touching moment when a woman told about the bleakness of her life without water in the Cameron Park colonia, but she told the story in Spanish and most of the media missed it.

The governor brought along four members of the Water Development Board, who promised quick action (and within a month four colonias had service). But neither the members nor the media realized the symbolic significance of the victory. It was like winning the World Series while the press was out to lunch.

After the meeting, Ernie gathered the entire membership in a corner of the convention hall and delivered his post-action evaluation. He gave the leaders high marks for attendance and exchange of power (they had gotten everything they came for and more), but only a C minus for drama. Overall, he said, the action deserved a B plus.

“What about the mariachis?” a man called out.

“The mariachis were good,” Ernie admitted.

“We worked hard just to get a B plus,” a woman said, and the members began to grumble and exchange nods.

“No matter what Ernie says,” another woman spoke up, “I think people did a damn good job and ought to be congratulated.”

Ernie gave them his cold glare, but this time it didn’t work. “Okay, okay,” he said. “I’m gonna raise that to an A minus.” There was general applause. Ernie Cortes was a real softy, and if the governor and the power brokers in Austin didn’t know it, everyone here did.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio