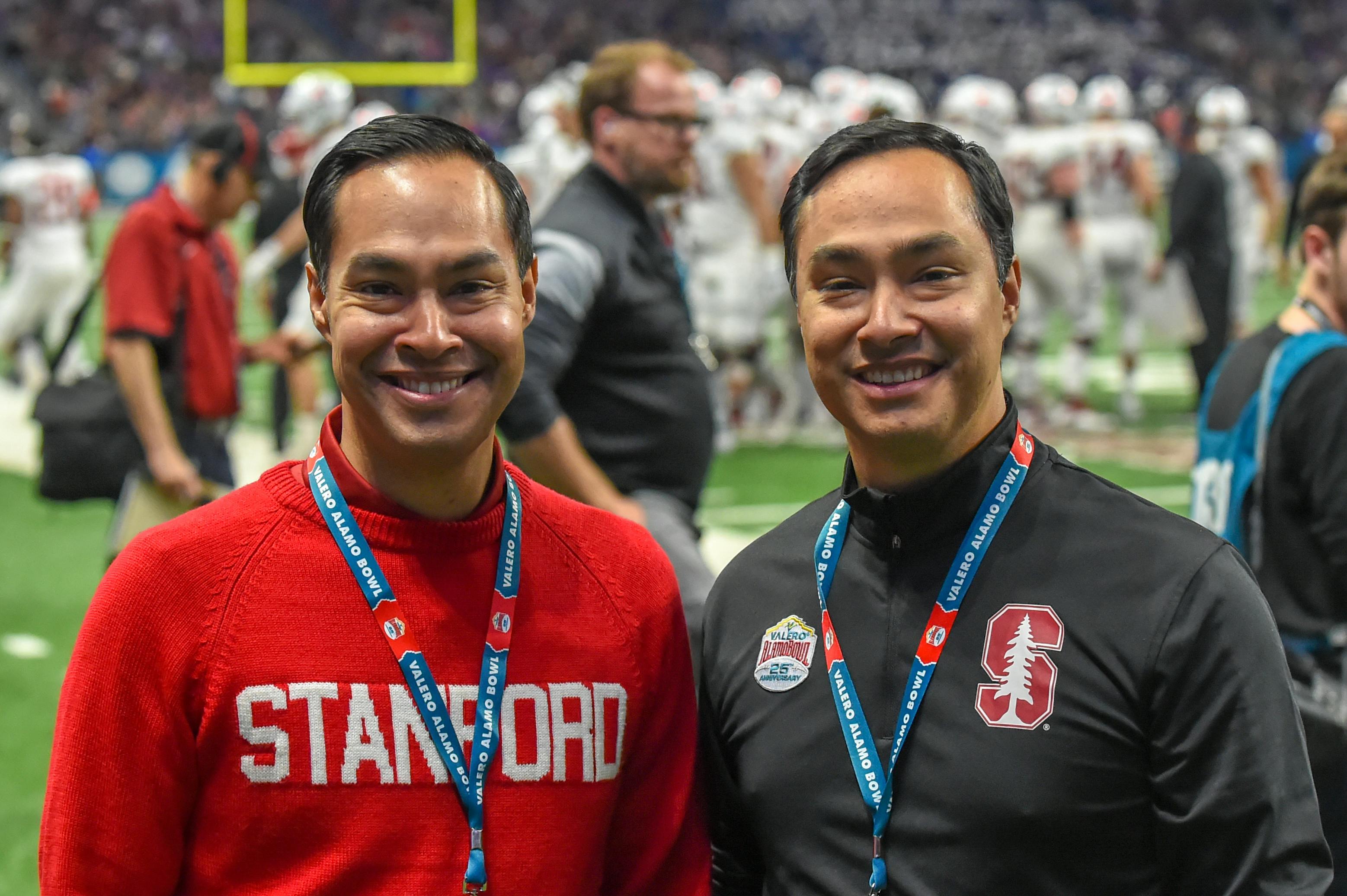

I sensed the airplane’s wheels lift off the ground, and the weightlessness I felt made my stomach turn. The wheels folded up into the plane and the hatch closed, triggering a tightness in my throat as I attempted to hold back a surging tide of emotions. At least I had [my brother] Joaquin sitting in the next seat, steeling me.

I looked over, and he was already staring at me, eyes wide with emotion. I watched them fill with water, and my lip started quivering. Then his lip started quivering.

We both emotionally collapsed at once, and boy, was it ugly. Hiccups, snot bubbles, sobbing. We didn’t care. We didn’t even know what we were crying about. We’d never spent more than a few days away from home, and we missed our family already.

Crying is hard work, but we were athletes, so we kept it up the entire fifty-five-minute flight to El Paso, our first stop. A flight attendant did a couple of passes before returning with a stack of drink napkins for us to wipe our tears away with. Dad must have bought us the cheapest tickets possible, because we flew from San Antonio to El Paso to San Diego to San Francisco. Seven hours of traveling, reminding me of those long bus rides and transfers that were the norm growing up without a car.

One of Mom’s activist friends had a son at Stanford Law School, and he met us at the airport and fit all our luggage into the trunk of his car. He drove us through the hills to Palo Alto and toward the East Bay, chatting away and giving us advice and encouragement as I stared out the window, zoned in on a new reality. We spent the night at his mother’s house, and in the morning he drove us to Stanford’s campus.

It felt as if we had driven onto the set of a TV show. Sandstone buildings with Spanish-tile roofs and palm trees lined University Avenue, and countless students on bikes crisscrossed each other’s paths in a sort of organized chaos. We stopped, and I stepped out of the car. The California sunshine was strangely cinematic, and the air felt and smelled different than in Texas, as the scent of freshly cut grass rose from manicured lawns and wafted in the breeze. Here we saw black squirrels scampering up trees, whereas we were used to seeing stray packs of dogs running through the early morning streets.

Stanford University is known as the Farm, a throwback to the days when founders Leland and Jane Stanford used the land as a horse farm—about eight thousand acres nestled between San Francisco and San Jose, in the heart of Silicon Valley. The campus had about seven hundred buildings, and a giant red S was planted dead center in an expansive front lawn. Seven thousand students lived on campus. Joaquin and I were excited and proud, and determined to succeed. We were starting fresh in a place where our background didn’t really matter in the ways it had in San Antonio. Everybody had gotten here somehow, and we were all on a level playing field.

“We were starting fresh in a place where our background didn’t really matter in the ways it had in San Antonio. ”

The undergraduate college at Stanford admits fewer than 10 percent of those who apply, and the university prides itself on being the center of technological innovation. Stanford alumni have founded many of the world’s most successful tech companies. When Joaquin and I arrived, the dot-com boom that would make billionaires of grads like Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page was still five years off, but the university was already famous for having launched the careers of tech pioneers like Bill Hewlett and David Packard.

Joaquin and I felt very far away from home, so we wanted to live in Casa Zapata, a Chicano-themed dorm named after the leader of the Mexican Revolutionary war, Emiliano Zapata. There was a lottery system and we didn’t get in; instead we were assigned different dorms on the east side of campus, across a grass field from each other. This would be the first time we had ever lived apart.

I was assigned to Soto, a freshman dorm in Wilbur Hall. As I walked up to check in with a group of college-age staffers at the reception table outside the entrance, they greeted me upon sight by shouting out, “Julián!” They pronounced it with a Spanish J and an emphasis on the a—not “JOO-lee-in,” but “who-lee-AHN.” All through school I’d grown up hearing the English-sounding Julian, even in Mexican American neighborhoods of San Antonio, and here in California, in a school with people from around the world, they nailed my name on the first try.

The school was immensely diverse, and you’d hear many different languages, accents, and slang terms in the hallways or in cafeteria lines. College is fantastic for a variety of reasons, but that opportunity to bond with people of very different backgrounds, to pull knowledge—big and small—from such a diverse pool, is invaluable, especially in the formative years.

Moving into a different environment like this gave me the space to truly appreciate and exhibit pride in my own background, including in my name. From then on, I always referred to myself as Julián, never Julian. I felt in charge of my life and my future, and that confidence informed my decisions in the years to come.

After settling into our rooms, Joaquin and I explored the new living areas. In a university known for pioneering modern advances, it made sense that the campus incorporated cutting-edge technology. Every dorm had its own computer room, with Macintosh desktops and one NeXT desktop available to students. Joaquin and I walked into the computer room in my dorm. At Jefferson we had used clunky, slow PCs and had seen a Mac once in a blue moon. To us the machine looked like an intergalactic control system. Joaquin needed to set up his email account, so he sat down at a terminal and hit the keyboard. Nothing happened. He picked it up and looked to see if it was plugged in. It was, and he fumbled around hitting the Option and Control keys and just making a symphony of error beeps.

Then he saw a small white gadget tethered to the computer by a cord and sitting atop a black foam pad. We thought it was some sort of presentation aspect of the computer, and Joaquin didn’t know what to do with it. He flipped it over and noticed a little plastic gray ball in the center. He rolled it with his finger. “Oh! Look!” I said, pointing to the cursor on the computer screen.

Joaquin tried to navigate it toward the line he needed to type on, but it jerked around erratically.

“What’s wrong with this thing?” he asked.

A student across the table was looking at us curiously. From a technological standpoint, we were like cavemen.

“You have to turn it over,” he said. “Like this.” He pointed at his mouse, sitting white side up on the black pad. We looked at him and then back at our mouse as if it were a Rubik’s Cube. Ours was like a flipped turtle, rocking back and forth as we flicked the gray ball, continually tipping it to one side. “Slide it on the pad!” another student yelled. How to use a mouse—my first lesson at Stanford.

There is a family story that haunted me during my arrival at Stanford. One of my distant cousins had dedicated himself to getting into a prominent college, found a way to pay tuition, and left home just like we did—amid tears and well wishes, a bon voyage to a new life. Two semesters later, he returned home, shell shocked. Actually, culture shock was how family members described it. There was no shame, only an odd sense of pride that the student had been accepted and yet made the choice to return to a loving home environment that couldn’t be found elsewhere.

During our farewell party, one of our mother’s friends had said as much to me. “I’m so proud of you! But, you know, if you ever don’t like it out there or can’t make it, then you can return here, and we’ll all be here for you.” It was meant as an expression of affection, but it felt like an expression of doubt.

“It was meant as an expression of affection, but it felt like an expression of doubt.”

Still, Joaquin and I had to find a way to adapt. You either cut it at Stanford or you didn’t. We had attended an overwhelmingly Mexican American high school in a majority Latino working-class community, and we’d barely left the county, never mind the state. And while there was some doubt about the quality of the academics at our school, we both knew that there were plenty of people at Jefferson who would have done well at Stanford if they had had the opportunity to go there.

We were mightily impressed by our surroundings, no question about it. A casual conversation with a classmate might hint at a superstar intellect. People were clearly smart, but I felt that if I worked hard, I could do well at Stanford. And, again, Joaquin and I had each other to lean on and prop up in times of stress.

My freshman roommate at Stanford had nobody to lean on. Hailing from a small town in the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas, he’d attended public school like me and was planning to study engineering, one of Stanford’s toughest majors. He struggled and sometimes overslept. Cell phones with unlimited calling were not a reality yet, and long-distance calls were expensive, so he couldn’t even find comfort by talking with old friends and family regularly.

When I needed to take a break, I would often walk over to Joaquin’s dorm or invite him to come to mine. We’d catch The Wonder Years or a football game on TV. Having my brother and best friend so close by made a world of difference, especially our freshman year.

My roommate, meanwhile, left after freshman year and never came back to Stanford.

It made my blood boil to think about the differences in opportunity among my Stanford classmates. Joaquin and I essentially had to forge our own path to Stanford ourselves while so many classmates were essentially put on a path to Palo Alto from very early on. They were all smart, deserving students who mostly worked hard to get there, but given the disparity in economic backgrounds, nobody could look at the routes taken to Stanford and say that they were equitable.

One evening at dinner, about a week after we’d arrived, we finished some slightly stale fish and were digging into multiple scoops of ice cream. One student mentioned how easy a history AP class was at his high school compared to his current class. There were groans of agreement.

“All eight of my AP classes were mostly just extra homework,” another student said.

“Eight? Lazy bastard. I took ten.”

“Loafer,” a third said, scooping too much chocolate ice cream into his mouth. “Whelfve.”

“What?” we all said.

“Whelfve,” he said, frustrated as ice cream started dripping out of his mouth. He tipped his head up, holding a finger out for pause as he swallowed.

“You make eating ice cream look hard,” Eight APs said.

“Twelve!” he finally said, his mouth clear of ice cream. “I took twelve AP courses.”

“I’d taken two AP classes at Jefferson—and the school only offered three.”

I was embarrassed. It wasn’t my fault, but I felt self-conscious about my comparatively threadbare education. I’d taken two AP classes at Jefferson—and the school only offered three.

This inequity in our country’s education system has never stopped seeming like one of our most chronic problems. It is painful to think of a kid forced to swim upstream, only to arrive at the same spot as somebody who had the opportunity placed in front of him. Sure, both kids have to achieve, but the effort and available support and resources are often incomparable. I understood, without any malice toward my friends at the table, what Mom and many others had fought for and how much further we all still had to go in this country.

Still, we’d gotten into Stanford, and now the rest was up to us. We didn’t have the academic background that many of our classmates did, but we made up for that with sheer effort. I studied more than I ever had before, taking breaks with The Wonder Years when needed and blasting music by Counting Crows and Selena to keep my energy up as I studied into the night. Scared that I would fall behind and be unable to escape the avalanche of assignments and test prep, I built in a buffer by staying two weeks ahead of all my reading assignments. I even bought a felt marker and wrote “PREPARE PREPARE PREPARE” on a piece of paper that I taped to the wall above my desk lamp. I’d sit down and look at my mantra before studying.

Soto was a three-story co-ed dorm with a reputation for being a boring place with bad food compared to the bigger dorms and the rowhouses on campus. But in my opinion, if you stuff enough college students into a tight place, it will be anything but boring.

Heyning, one of my dorm mates, was a five-foot-five math whiz with thick glasses and a high-pitched voice. If he had been cast in a movie, he might have seemed like a stereotype of a smart student. But Heyning was all real and all genius, and he quickly became one of my favorite people to bump into late at night. He’d get stressed and find comfort pacing the hallway at night, jangling his keys like a janitor. Joaquin and I were often at each other’s dorms, and we’d never pass up a chance to talk to Heyning as he paced. Not only was the guy beyond smart, but the way he thought of life and the world was refreshingly unique. One night we heard the sound of his keys and I opened my door to say hi. He nodded to us, and we started a conversation in the hallway. Joaquin was talking about a cute girl in one of his classes. Heyning shook his head.

“What?” Joaquin said. “You don’t even know her!”

“No girls,” he said.

“You don’t like girls?” I asked. I didn’t care who he liked, but I was curious that he didn’t want to get involved in any relationships. We were at college, after all.

He tapped his head. “Reptilian side of the brain, the primitive part.” He shook his head as if to fight its influence, as if just mentioning it called it to attention. “First to develop. If I shut that out then I can focus on my studies. It’s just a distraction.”

“Just a distraction?” Joaquin said and laughed. “But it’s, like, one of the best distractions!” I said.

Heyning respectfully disagreed. I wasn’t going to argue with his logic—I knew what kind of grades he got.

Then, as a contrast, there was Jon. A Californian in the mold of Jeff Spicoli of “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” he always seemed to be holding a beer in one hand and dribbling a basketball with the other. Jon was a lesson in how you can succeed and still be relaxed. After all, he wasn’t smoking weed at the beach—he was at Stanford! He had that magical California nod that only a native acquires. It’s a fluid, welcoming gesture that can only be interpreted as saying, “This is pretty good, isn’t it?” And when you live in a place that averages seventy degrees and is sunny all the time with miles of beautiful beaches, then, yeah, just like with Heyning, I wasn’t going to argue with that logic.

Dorm life was also my social life. The surrounding town, Palo Alto, was an affluent community that had some nightclubs, but going there was never something Joaquin and I felt comfortable doing. We didn’t own a car or bikes, and we rarely ventured off campus. We were happy enough just hanging out with friends in a dorm lounge or at a campus party.

As inviting and casual as those gatherings were, it still took some time before I felt comfortable. I hadn’t attended many high school parties, and at college we were thrust into a completely different culture. The first party I went to at Stanford had a keg, and the place was already littered with Solo cups when I arrived. I began talking to a few folks and noticed a sea of red cups bobbing around me. I continued talking but could not stop fixating on those cups, which seemed like some trendy accessory that I needed to have.

Except that I didn’t drink. As a child, I had learned to keep a casual distance when Mom’s friends gathered to drink—always fun and relaxed at first, but as the beer cans emptied, the atmosphere changed to one of blustery emotions, with charged bursts of hysterical laughter and occasional heated arguments. I wondered why these smart, pleasant people would do something that turned them into lesser versions of themselves. Growing up, I tried not to pass judgment when people drank, but I had no desire to do it myself.

The embarrassing part of that first Stanford party was how insecurely I reacted to my peers’ drinking. My dorm mates weren’t even noticing that I didn’t have a drink in my hand, but I did and felt out of place. This had nothing to do with drinking and everything to do with my confidence and image of myself. I excused myself from a conversation, went over to the leaning tower of Solo cups, and took one off the top. I went to the bathroom and filled the cup with water, then spent the next two hours at the party slowly sipping tap water. I only did that once, but it made an impression on me. I realized that I would be much better off just being myself around people. That way I’d attract friends who liked the real me, not some person I was trying to be.

Then, the zits came. I guess they were technically zits, but what began emerging from my face were basically miniature volcanoes bubbling upward with so much pressure that the skin discolored into deep purple patches. I knew it was bad as I was walking out of the dorm and ran into a friend.

“Julián! You get your ass kicked?”

I looked at him questioningly as he leaned in for a closer look.

“Oh, those are . . . what are those, zits? Those are massive.”

Having painful zits like bruises made me less inclined to venture into the Solo cup jungle, so I went into hermit mode until I could see a doctor back in San Antonio. The man was in his seventies and far from the picture of health one hopes to see in a doctor. When he looked at my face he nodded immediately, as if he’d been diagnosing the problem for the last fifty years, which he probably had.

“Cystic acne,” he said and without missing a beat, almost with perfect comic timing, he continued: “Don’t worry, it’ll go away in four or five years.”

Okay, no offense to older people, but the sense of time is very different for a young person when it comes to acne. Four or five years was my entire adolescence at that point, whereas it was just a fraction of time for this man. Not to mention that it was the entire time I’d be at college.

Fortunately, I managed to find my pace at Stanford and stopped stressing so hard. Life at school was all about maintaining a rhythm and not feeling overwhelmed, and I eventually found that groove. The pimples thankfully receded in a matter of months, not years.

Growing up, Joaquin and I were essentially immersed in Chicana activism. Because that had always been our worldview, as well as a force in the community around us, we had a skewed perception of how that played into the greater American sensibility.

Early on at Stanford, I was writing a paper for English class, a personal essay about my background. I was on the Macintosh, and as I typed, I noticed red squiggly lines underlining spelling mistakes. Great! I no longer needed a dictionary on my desk for reference. I finished my paper and was reviewing it, correcting the misspelled words by clicking the mouse button and deciding which correct spelling to use. I always was given the correct replacement.

Almost always.

“Chicano” was written throughout my essay, but every time it had the red squiggly line underneath. I highlighted the first instance and hit the button. Microsoft Word made a recommendation: did I really mean “Chicago”? That made me think about how relatively unknown, even invisible, the Chicano community was to the vast majority of Americans. It meant a lot to me growing up, but most people didn’t even know what “Chicano” meant. And, I thought, the majority of Latinos probably don’t consider themselves Chicanos.

That said, at that age I wasn’t keenly aware of the discrimination that others experienced. There were few Jewish, Native American, gay, or transgender people in my childhood circle. My small group of friends from kindergarten to high school were all Mexican American, and the fight for civil rights was highly personalized in my household and area of the city.

I would not be surprised if other students heavily submerged in other ethnic cultures encountered the same sense of marginalization when they wrote their papers on the Macintosh. One of the most interesting classes I took, “Europe and the Americas,” detailed the systematic and brutally efficient decimation of indigenous peoples and cultures. One of the required books, I, Rigoberta Menchú, recounted the struggle of indigenous Guatemalans. Later on, in “Imagining the Holocaust,” I heard the horrific account of what happened to Jews during World War II. At Stanford I was forced to pull back from my tight community and understand how a common thread ran through so many other cultures around the world where people had to fight for their rights. When one of these groups achieved a victory against discrimination, I felt like the mother at the bus stop who had asked if “we” had won the election.

Joaquin and I would keep an eye on cheap flights and fly home during some of the breaks. Every time we returned, it didn’t feel quite the same as it had before we left for college. It’s natural to notice changes in yourself when you return to your old stomping grounds. Most people think dorm life is cramped, but our room at home felt like a car trunk. It was almost too small for one person, and now it seemed ridiculous and extraordinary that my brother, Mamo [my grandmother], and I had slept in that space all those years. Joaquin and I couldn’t even pass each other in the room without bumping. Only two feet separated Mamo’s daybed and our bunk bed. Mamo had filled her closet with clothes and mementos while Joaquin and I managed to stuff our clothes into one dresser.

“Mamo’s health was more concerning. Of course, Mom was well aware of Mamo’s issues.”

Mamo’s health was more concerning. Of course, Mom was well aware of Mamo’s issues.

“Remember when she was discharged from the hospital after we thought she had the flu?” Mom said. “She’s hardly walked out of the house since. She has a hard time walking the five feet to the bathroom and back to her sofa and her bed, and it’s getting worse.”

I thought about how she went out to the porch to see us off to Stanford. The thought that she could barely walk out that front door these days made me sad. Mom was on her own with this, and it pains me to say it, but Mamo only made it worse by never taking medicine and ignoring almost every issue until Mom was forced to deal with it. Mom loved Mamo, but she often seemed in over her head now. As prepared and wonderful as she had been caring for Joaquin and me, Mom seemed less prepared and less able as a daughter to care for her mother. Mamo was so passive toward life that she was a tremendous responsibility for Mom.

“It hurts to say, but we may need to think about a nursing home,” Mom said.

“Ugh,” I said. “I’ve heard so many horror stories about nursing homes—all the neglect, lack of cleanliness, abuse by other residents and the staff.”

We all nodded. Our reluctance was cultural too. Respect for elders within most Latino families demands that they be cared for in the home.

“We need to also think about Mamo getting the care she needs,” Joaquin pointed out. “She is sick, and maybe being in a place that could regularly administer medicine would actually make her healthier.”

“If it gets any more demanding…” Mom trailed off, shaking her head. “I can’t do much more, and when I’m at work I’m constantly worrying.”

Caring for Mamo did get much more demanding, and Mamo went in and out of the hospital as her diabetes worsened. One time, we flew home to see her, and when Mom, Joaquin, and I walked into her hospital room and said her name, there was no response. She seemed somewhat awake. I waved and waited for that trademark Mamo smile, but she was clearly struggling and confused. Then she was still, as if fighting for consciousness. We held her hand, and slowly she began to whisper, but her words made no sense. Then she dropped out of consciousness.

Mom hurried out of the room and returned with two nurses, who began treating Mamo for diabetic shock. Clearly, she could no longer live at home. We looked at nursing centers, and Mom decided on Retama Manor, where Mamo would receive constant supervision.

We were familiar with Retama Manor, which was near our old house on Hidalgo Street, across from the San Fernando Cemetery and a string of shops that sold piñatas. Its odd location lent a strange atmosphere for people visiting relatives there. Every time the three of us visited, there was a tenant parked out front, brakes locked on the wheelchair, taking long drags on a cigarette. If the piñatas weren’t a dead giveaway for the area’s demographics, then the soundtrack for the nursing center made it obvious. You’d walk in the front door and be assaulted by TVs blasting telenovelas, far too loud for anybody but the aged viewers in the compact living room.

Mom visited Mamo several times a week, and Joaquin and I fast became locals when we came on breaks. We never expected Mamo to fit in, but she seemed energized by her new environment. During one visit, Joaquin and I were talking to her when she stopped and pointed to a dapper old gentleman strolling down the hallway in loose-fitting clothes.

“That’s the one,” Mamo said and giggled. “He’s dated three ladies here. He tried to talk to me, but I wasn’t interested.”

The three of us were amazed that Mamo not only accepted being in a nursing home but seemed to take to it. The timing of the move was right too, for she began needing more and more care on a regular basis.

Astonishingly, Mamo García [Mamo’s guardian] moved in to the same nursing home. Mamo’s guardian had truly ended up being with her for life. Although Mamo still had a complicated relationship with her, the two of them were family, and Mamo was happy to be with Mamo García again.

Excerpted from AN UNLIKELY JOURNEY by Julián Castro. Copyright @ 2018 by Julián Castro. Excerpted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, lnc. All rights reserved,

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Books

- Julian Castro

- Joaquin Castro