This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It was the next to last Friday before Christmas, and Vin Boemio was on the spot. He was sitting in his domain—the oil trading room of Bomar Oil, on the thirteenth floor of a high rise in midtown Manhattan. Outside, throngs of holiday shoppers were enjoying the unseasonably warm weather. But inside the Bomar trading room, the atmosphere was chilly. Boemio was trying to decide what position to take in the spot market. All morning long he and his two-man staff had been embroiled in a debate over the future of world oil prices.

The outcome of that debate—and debates taking place in other trading rooms—would reverberate across the globe. For Vin Boemio and his assistants are part of a select, almost clandestine circle of no more than a thousand people who make their living by trading crude oil on the spot market. Because of their secretive ways, big-time international oil traders move in a shadowy and poorly understood milieu. Yet, while OPEC ministers still go through the motions of establishing the official price of oil, today the real price fluctuates according to the workings of the invisible hand of the spot market—a hand made up of traders like Vin Boemio.

Spot market trading may be the trickiest business in the entire oil game. It requires instinct, guesswork, and nerves of steel. Companies like Bomar don’t produce or refine oil; rather they are classic middlemen who buy and sell cargoes of crude that won’t be delivered for months, oil that hasn’t even been pumped out of the ground yet. The right call can mean huge profits; the wrong call can mean equally huge losses. But spot market traders don’t merely react to world oil prices. Through their collective buying and selling, they play a major role in determining what those prices will be.

Boemio’s command post at Bomar looked like a high-tech poker parlor. Sealed off from adjoining offices by soundproof interior walls, the trading room was dominated by a large rectangular table equipped with four chairs, four telephones, and a remote-control video screen. Like oil traders at most other companies, the Bomar traders shared a common work space in order to exchange news quickly. But on the morning of December 16 what they were exchanging was sharply differing opinions.

“There’s no goddam way the British are going to cut their official price,” Boemio insisted. “The Saudis won’t let them. If the British cut their price, then the Nigerians are going to have to cut their price too. And if that happens, the bottom will drop out of the market, and OPEC will collapse.”

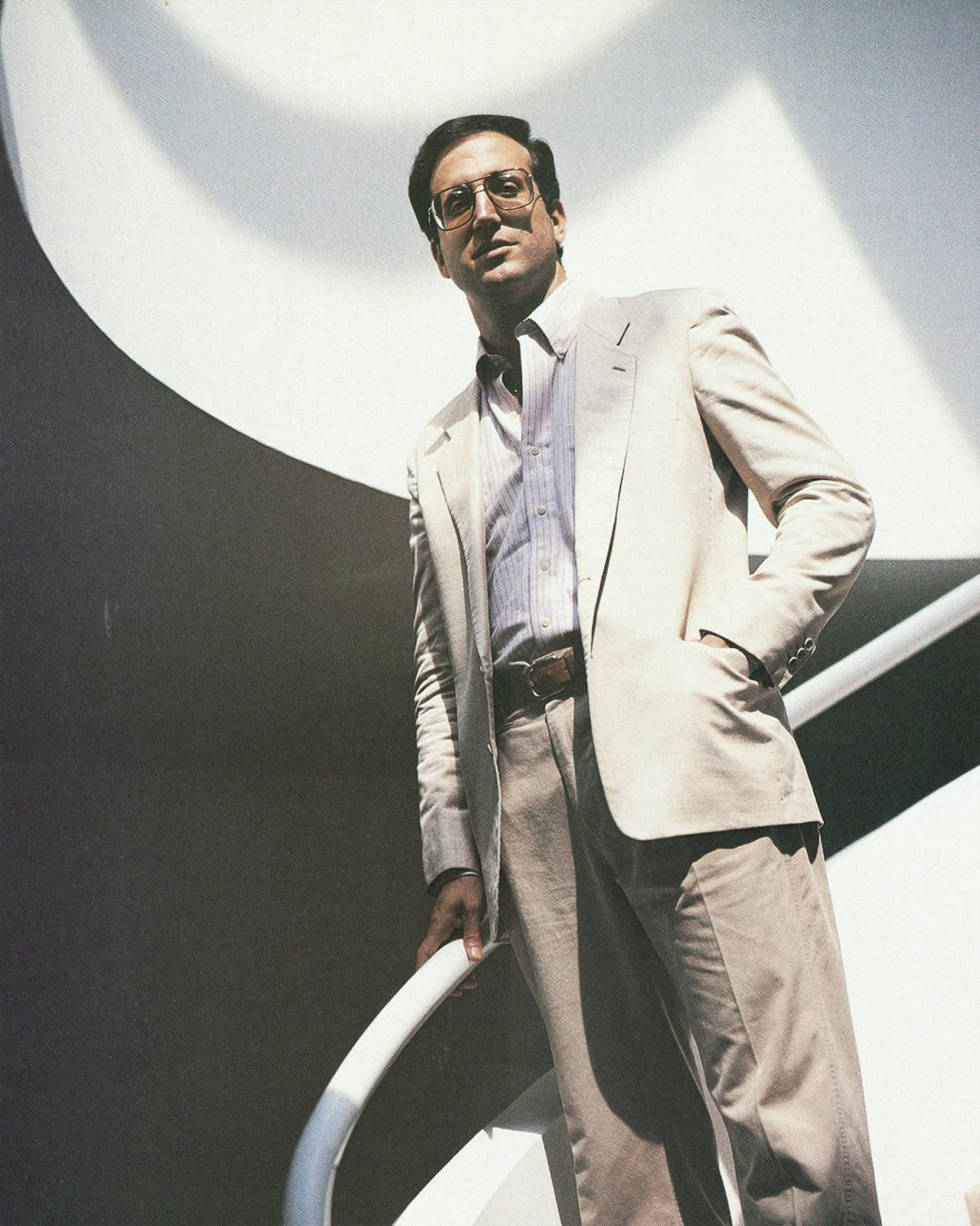

Boemio looks every bit as tough as he sounded then. He is six feet four inches tall, a broad-shouldered man in his mid-thirties with thick brown hair, an aquiline nose, and gold-rimmed glasses. From certain angles he bears a slight resemblance to actor Sylvester Stallone, and like Stallone’s Rocky, Boemio takes great pride in his street smarts. The son of an Italian bricklayer, he is a self-made millionaire who has spent more than a decade matching his wits against the other members of his profession.

Boemio was bullish that morning. He felt strongly that world oil prices were going to rise in the winter months ahead. He wanted to “go long”—that is, buy a cargo of crude (a tanker holds about 500,000 barrels) on the spot market right away in the anticipation that he would be able to sell it at a profit. His subordinates, however, felt just as strongly that the price was about to fall because of the continuing oil glut. They thought their boss should either “sell short”—that is, sell a cargo now and cover the transaction later, when, they hoped, the price had dropped—or stay out of the market entirely.

“The British have to cut their official price,” one of the assistants argued. “If they don’t, they’re going to lose their long-term customers. And the same goes for OPEC.”

Around and around they went, until Boemio finally ended the discussion. It was his opinion that Bomar should buy, and since he was Bomar’s chief oil trader, his opinion was the one that counted. He told his men to get on the phone and look for prospective sellers. Then he picked up his own phone and called a friend at First National Oil Brokers in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

“Confidentially,” he said, “I think I’m going to be a buyer. We’ve just started to scout around. I want you to scout around for us too and get back to me in an hour.” Boemio hung up and did the only thing a spot market trader can do at such a moment. He sat back and waited.

If a market can ever be called ethereal, then that describes the spot market. As with any commodities market, the vast majority of its buyers and sellers hope never to see the product they are trading. But unlike other commodities markets, the spot market has no rules or regulations, no official clearinghouse, no Big Board flashing the latest bids and asks. It cannot even be said that the spot market exists in any one place. The fraternity of spot market traders operates mysteriously but efficiently, buying and selling over telephones and telexes. Their deals are usually secured not with collateral but with blind trust. Their transactions are always confidential. Their only law is the law of supply and demand.

No standard public index lists the exact spot market price of a particular type of crude on any given day. In fact, nobody even knows how much oil is produced on any given day. Traders keep logs of transactions, but even those are not completely verifiable, since traders must rely on the grapevine for much of their information. Platt’s Oilgram Price Report, a daily newsletter published in New York, provides the most widely respected summary of spot market activity. But even Platt’s relies largely on confidential telephone surveys of trusted industry sources. Oil traders are under no obligation to report their dealings to Platt’s or anyone else, and many refuse to cooperate even anonymously in market surveys.

For all its mystery, the spot market is now the most dominant factor in establishing the price of oil. Before the Arab oil embargo of 1973, the huge, dominant oil companies known as the Seven Sisters controlled the market. After the embargo, of course, OPEC took over, driving up prices almost at will. But today, thanks to the oil glut, both cartels are in retreat, and the forces of the marketplace have regained their natural supremacy. The spot market rules not by official consent but by leverage. Although the majority of the world’s oil production is still bought and sold under long-term contracts at the official price, anywhere from 20 to 40 per cent—roughly 10 to 20 million barrels a day—is traded under short-term contracts on the spot market. By even the most conservative calculations, that is more than enough oil to provide the difference between an energy crisis and energy security for this country in the event of a cutoff of supplies from the Persian Gulf.

Boemio’s decision to buy a cargo of crude oil last December was one in a series of spot market transactions that took place over the course of several months. Although his judgment would have multimillion-dollar consequences for Bomar Oil, there was nothing especially unusual about it. Boemio made decisions like that every day. Indeed, most of the transactions in the entire series were fairly typical of the spot market.

Boemio was buying crude oil in December that would be pumped from the depths of the North Sea the following March. By the time those North Sea cargoes of oil reached their final destinations, they had been bought and sold on the order of four hundred times, at prices ranging from around $28 a barrel to around $31 a barrel. But because the oil trading community is such a closed society, not all of those transactions can be traced. Enough of them can be followed, though, to give a sense of how the spot market works and why the decisions made by the people who play that market—men sitting in their tiny trading rooms, confiding their trades only to each other—affect us all.

The Loneliest Trader in Rotterdam

In a quiet Rotterdam neighborhood, huddled discreetly amid a row of centuries-old brick townhouses and facing a tree-lined canal, there sits a three-story glass office building that is the headquarters of a company called Vitol. Company president Jacques Detiger, a trim, handsome Dutchman in his late forties who favors well-tailored suits and expensive cigars, is the epitome of the worldly-wise oil trader. In 1966 Detiger started Vitol with $10,000; today it is a $5-billion-a-year energy conglomerate and one of the largest traders of crude oil and refined products in the world, with interests in Europe, the U.S., the Persian Gulf, and Russia.

Since Rotterdam and the spot market are so closely aligned in the public mind, the industrial Dutch city might seem the perfect place for Detiger to conduct his business. But such is not the case. Vitol is the last big company to base its operations in the former spot market capital. “I live here because I am Dutch and I happen to like it,” Detiger says. “The idea that Rotterdam is the center of oil trading is total fallacy.”

It wasn’t always that way. Rotterdam’s reputation as the capital of world oil trading can be traced to the chaos that followed the 1973 embargo. At that time the spot market handled less than one per cent of the world’s crude oil and was regarded by major refiners as merely a mechanism for coping with temporary shortages and excess inventories. But after OPEC took center stage and quadrupled prices, the old ways of doing things quickly fell by the wayside. Oil producers, in their eagerness to capitalize on rapidly rising prices, began reneging on long-term contracts and selling more and more crude under short-term arrangements that often involved middlemen.

Overnight, it seemed, the spot market had become the world’s hottest crapshoot, and a new breed of independent oil trader rushed onto the scene. As Detiger points out, the independents existed largely because the major companies, wary of jumping into the fray, allowed them to exist. Few of these new players in the oil market game had experience in the fundamentals of exploration, production, and refining. They were primarily financial speculators—con artists, impoverished aristocrats, former tennis pros, ambitious young college and B-school grads looking to make their fortune as fast as they could. They operated the way middlemen always do, cutting the risky deals and even at times paying the bribes and foreign “commissions” the majors tried to avoid.

These new oil entrepreneurs saw Rotterdam as the ideal place to set up shop. Strategically located at the point where the Rhine flows into the North Sea, Rotterdam boasted the world’s busiest harbor, a thirty-mile-long ship-clogged canal that handled over 200 million total cargo tons per year. Rotterdam was also the site of Western Europe’s biggest refinery complex, and most oil cargoes exported from the Persian Gulf and the North Sea funneled through it. So the traders moved there en masse and then turned out their umbrellas upside down and waited for it to rain money.

They didn’t have long to wait. Between 1973 and 1980 the spot market produced some of the most spectacular rags-to-riches stories in the history of the genre. As crude-oil prices soared from less than $4 a barrel to more than $40 a barrel, a trader could make himself a millionaire on just one deal. “It was like picking up gold off the streets,” recalls Boemio, who should know. He got his first big break in the oil trading business in 1975 when he was hired as a trader by Philipp Brothers, now a division of Phibro-Salomon—one of the two largest oil trading firms in the world (the other is Transworld Oil). By 1975, at the ripe old age of 27, he was making a seven-figure income. He estimates that, incredibly, that put him in only about fortieth place on the corporation’s salary scale.

One trader remembers what it was like during the halcyon days: “Guys who had been making thirty thousand dollars a year working for someone else in another business suddenly started making a million-plus and were driving Corvettes and Ferraris. They got into offshore bank accounts, expensive drug habits, fancy restaurants, high-class hookers, and some serious marital problems. The vibes created by so much money coming in so fast were awesome. Everybody was getting so rich so fast, we thought the party would never end.”

But, of course, the party did end. One of the things that had led to such easy wealth was federal price controls in the United States. Government regulations were full of legal loopholes. The rules could also be exploited by unscrupulous speculators who set up illegal daisy chains—schemes in which controlled oil was, in effect, laundered so that it would become uncontrolled. But by 1981, price controls had ended, and soon thereafter came the oil glut. There weren’t any more easy deals.

The postderegulation shakeout left blood on the streets in all the major trading cities. In 1979, at the peak of the good times, there were more than four hundred companies trading crude on the spot market; today there are fewer than a hundred concerns remaining, and about thirty of them are based in Houston. Boemio was one trader who landed on his feet, though. In January 1983 he was asked to set up an oil trading subsidiary for Bomar Resources, a multinational commodities firm backed by Jacob Rothschild. When he signed on, Boemio was guaranteed a healthy salary and a percentage of the profits he brought the company, but he is the first to admit that he wasn’t making the kind of money he’d made a few years earlier.

A lot of traders, however, weren’t as lucky. The best-known example is the infamous Marc Rich, who built a multimillion-dollar international commodities empire between 1973 and 1981 in Horatio Alger fashion. Then the Justice Department alleged that he had made at least $105 million of his money by manipulating daisy chains. Now Rich is best known for fleeing to Zug, Switzerland, one step ahead of the posse, and becoming a fugitive in one of the largest tax fraud cases of all time. Boemio says that partly because of the shakeout and partly because of the unwanted publicity generated by the Rich case, “the industry is even more of a cliquish, close-knit fraternity than it was before the glut.”

Although the fortunes of the oil traders are at an ebb, there is more activity on the spot market today than there has ever been before. The biggest traders, Phibro Energy and Transworld Oil, each handle up to sixty cargoes (30 million barrels) a month; most major U.S. independent traders trade about twenty cargoes a month; even smaller independents, like Bomar, trade as many as ten cargoes a month. But there’s a good reason for this seeming paradox. Back in the seventies the crude market moved in increments of 25 to 35 cents a day and $1 to $5 a week. Now crude-oil prices generally fluctuate in pennies, nickels, and dimes. To buy a cargo of $30-a-barrel oil requires an investment of $15 million. If it is then sold at a 5-cent-a-barrel gain, the gross profit is only $25,000. Today trading companies often have to move multibillion-dollar volumes of crude to squeeze out a $1 million profit.

The other big change in the business was that the oil trading community all but abandoned Rotterdam. As the hot young oil traders got rich, they also got bored with the city. Since they did most of their business by phone, they realized that they could do it anywhere. In fact, it made a lot more sense to be near the big banks and the headquarters of the big oil companies than to be situated next to the refineries in Rotterdam. So one by one they moved to cosmopolitan oil centers like London and Houston, where it was much easier to make—and spend—all that money. “I used to have lunch with somebody in this industry every day,” sighs Detiger. “Now my people in London and New York do that. I usually eat a sandwich at my desk.”

Mr. Boemio Guesses Up; Mr. Flyg Guesses Down

At just about the same time Vin Boemio was concluding that conditions were right to buy a cargo of crude on the spot market, another oil trader sitting in a trading room less than fifty miles away was coming to the opposite conclusion. He was one of Jacques Detiger’s people, operating out of Vitol’s offices in Stamford, Connecticut. His name was Richard Flyg.

A reserved former Mobil executive in his mid-thirties, Flyg has light brown hair, a neatly trimmed moustache, and an enviable reputation as a sharp, conservative, and consistently successful trader. Most of Vitol’s Stamford traders deal in refined products; Flyg, however, specializes in U.S. and North Sea crudes. He was working the phones hard that December day, calling one industry contact after another and asking each of them the same question: “Do you have a number for Brent?”

Brent is a blend of North Sea oil produced by a handful of prolific underwater fields off the coast of Scotland. It flows through the pipeline at a rate of about a million barrels a day, accounting for nearly half of the United Kingdom’s output. The U.K., in turn, currently provides more than 10 per cent of U.S. oil imports, which puts it a distant second to Mexico (23 per cent) but slightly ahead of Saudi Arabia (now only about 9 per cent).

American refiners like Brent for two main reasons. It is a “sweet, light” crude (it’s low in sulphur content and easier to refine than “sour” and “heavy” crudes), so it yields a higher proportion of essential refined products like gasoline and heating oil than do other types of foreign crude. Brent’s value is further enhanced because it comes from the British sector of the North Sea and not from the OPEC nations. Refiners who buy Brent know they are getting a high-quality crude from a reliable supply source.

In the wake of the oil glut and the discord within OPEC, Brent has replaced Saudi Light as the marker crude of world oil trading. Just as the blue-chip companies that make up the Dow Jones average set the benchmark for the stock market, so does Brent set the benchmark for oil prices. Although Brent is the most popular of the three major varieties that come from the British North Sea, it is only one of forty kinds of crude available on the world market. Each type has a different quality rating and a different price. But the price of Brent helps determine the prices of other grades, especially the very similar crudes from Nigeria, Algeria, and Libya.

Like most foreign crudes, Brent is the victim of a double standard; it has an official price and a spot market price. The official price applies mainly to long-term contracts and changes only by decree of the producing country, Britain in this case. The spot market price applies to oil that isn’t already under long-term contracts, and it is almost constantly changing according to the whim of the spot market. Because oil supply and demand are never in perfect balance, the official price and the spot market price are rarely the same. Shortages push the spot price above the official price; gluts drag the spot price down from the official level. Changes in the official price usually reflect long-term trends, while changes in spot prices mirror daily events.

Richard Flyg knew as well as anyone that spot market cargoes of Brent had been trading well below the official price of $30 a barrel for the past three months. Back in August, Brent had been selling for more than $31 a barrel, a high for the year. But prices declined in the fall, hitting a low of $27.76 in early December. Although Brent enjoyed a pre-Christmas rebound, it was now hovering around $28.50. But unlike Vin Boemio, Flyg believed that the price was going to keep heading downward.

“To me, trading Brent is just a guess on what’s going to happen in the Middle East,” Flyg said later. The British crude is an oil buyer’s hedge against instability in the Persian Gulf. As long as supplies from the OPEC countries remain stable, the price of Brent remains stable. But even a hint of trouble is usually enough to cause the price of Brent to move upward, since any cutoff in the Persian Gulf would immediately make it vastly more valuable.

When Flyg started guessing about the Middle East that day, what he thought about first was the ongoing Iran-Iraq war. Yes, Iran had threatened to choke off supplies in the gulf, but it hadn’t done so yet, and Flyg didn’t think it would in the near future. He also knew that the OPEC cartel had cut its daily output almost in half, bringing financial hardships to all but the richest countries. Glut or no glut, further cutbacks any time soon were unlikely. From Flyg’s point of view, it was plain that oil would keep flowing from the Persian Gulf, the glut would continue, and prices would inevitably decline.

Vin Boemio saw things differently. To him, the key points were these: a week earlier, OPEC ministers meeting in Geneva had agreed to stick with their official price of $29 a barrel for 1984. Just two days earlier, the British National Oil Company (BNOC), which sells Brent, had announced that its official price would remain $30 a barrel for at least the next three months. Though many oil traders had expected BNOC to hold the line on its official price, what struck Boemio was the timing of the announcement. It had come much earlier than expected, and he read that as a sign of resolve.

Flyg was aware of these facts too, but they didn’t change his opinion. He envisioned a scenario, for instance, in which Iran, desperate to finance its war effort, started an internecine OPEC price war by selling large volumes of oil at a discount. That would further depress the price and add to the glut. Flyg had also heard rumors in New York trading circles that the U.K.’s stay-firm stance was a bluff, that BNOC was prepared to cut the price of Brent by $1 a barrel in the coming weeks.

“There was a general feeling that we had an oversupply of crude,” Flyg noted later. The view through the picture windows of his office on December 16 hinted at one of the reasons why. It was a crystal-clear morning, and the temperature in the New York area was approaching 50 degrees, consistent with the mild weather that had persisted throughout the fall. The abnormal trend had been great for football fans but disastrous for crude-oil refiners. Back in September, as the summer driving season ended and the fall heating season began, most refiners had made the traditional biannual switch in output ratios. Typically, the balance shifted from 55 per cent gasoline and 25 per cent heating oil to 45 per cent gasoline and 30 to 40 per cent heating oil (with the remainder split between products like lube oil, diesel fuel, and jet fuel). Just as department store retailers counted on strong pre-Christmas sales to generate the majority of their annual revenues, refiners banked on a strong fourth-quarter demand for heating oil to produce their year-end profits.

But the mild autumn had put a crimp on heating-oil consumption, causing a reaction that was felt all the way back up the supply chain to the spot market in crude. Refiners who had replenished their crude stocks at the end of the summer now found themselves stuck with heating oil that was selling much too slowly. The price of heating oil had fallen from a January high of around $1 a gallon to less than 75 cents a gallon. Because high interest rates made it expensive to maintain surplus supplies, refiners were reducing their crude runs and drawing down their current inventories of heating oil.

Flyg believed that something had to give. The U.K. couldn’t insist on selling Brent for more than the market would bear, and in the current market $30 a barrel was pushing it. By the same token, U.S. refiners couldn’t keep drawing down their inventories indefinitely. He thought that over the next few months crude prices would drop, that perhaps the official prices would even have to be revised downward. But he also thought that in the short term—that is, as soon as the weather got cold—heating-oil prices were bound to go up.

Flyg decided that the time was right to short the spot market in crude oil. So, like Boemio, he picked up the phone and called a friend at First National Oil Brokers in Fort Lee. But instead of instructing his broker to look for potential crude sellers, as Boemio had, Flyg asked him to line up a buyer. Then he too sat back and awaited the market’s response.

London’s Stiff Upper Lip

Thirty-five hundred miles away, in the London headquarters of the British National Oil Corporation, Colin Darracott was fighting to keep spot market prices of Brent from breaking. Perched behind his cluttered desk, his phone practically glued to his ear, Darracott kept glancing nervously at his video screen while chattering away in a blithely reassuring voice that masked his true concern. He had participated in the decision to keep BNOC’s official price at $30 a barrel. Now he had to help defend that decision with the only weapon at his disposal—his powers of persuasion.

With his mop of light brown hair, darting blue eyes, and puckish grin, Darracott looks a bit like a mischievous schoolboy. But at the age of 35 he already has thirteen years of experience in the business, much of it acquired while working for Shell International in Canada, Curaçao, and South Africa. As manager of supply coordination for the state-owned BNOC, he is, among other things, one of the British government’s chief spot market troubleshooters.

At BNOC Darracott has to play both businessman and politician. Most traders answer only to their bosses and corporate shareholders. But BNOC’s management reports directly to Britain’s Secretary of State for Energy, who answers to Parliament and thus the general public. Being a public figure in a zealously private industry doesn’t make Darracott’s job any easier. As he noted with evident frustration, “The press is always pestering you.”

The public pressure on BNOC is a natural by-product of the company’s ambitious mission. Created in 1976 by the Labor government, BNOC was intended to be the vehicle for national participation in the North Sea oil boom. Thatcher and the Conservatives subsequently spun off the company’s exploration arm into the privately held Britoil. The company that remains functions as the marketing arm of the world’s sixth-largest oil-exporting country. About 60 per cent of the total North Sea production, or roughly 1.3 million barrels per day, is sold by BNOC, and its gross sales of $12 billion per year account for the majority of the U.K.’s annual oil income.

Most of BNOC’s sales are to customers under long-term contracts at the official price. Obviously Darracott and his colleagues prefer such arrangements. But because the oil glut has taken its toll on long-term customers, BNOC has been forced to become an increasingly active player on the spot market. In the last few months of 1983 it was trading at least 150,000 barrels a day, or about ten cargoes a month, on the spot.

In addition to marketing oil, BNOC sets the official price of Brent and other North Sea crudes. That price is a calculated business judgment based on what BNOC believes the market can bear, and the process of making that judgment is fairly complicated. Every three months a dozen executives from the company’s supply and trading departments sit down together and try to arrive at a realistic consensus. Proposals for official prices are based on input from company management, the government, traders at other firms, and sources at various industry periodicals. Although the U.K. is not a member of OPEC, it does maintain a working dialogue with some of the major OPEC producers. “We have a polite exchange of views” is how Darracott puts it. But even after the price has been set, there is no guarantee that it will stick. If BNOC has gauged the market incorrectly, its official price can—and almost surely will—crumble. As Darracott readily concedes, “What is known as the official price is really a very transparent price.”

In mid-December 1983 the dickering over BNOC’s official price for Brent was, as the British might say, rather heated. Big North Sea producers like Shell and Exxon, who were also big BNOC customers, were quietly voicing support. (Many producers prefer higher prices, even when they’re buying oil.) But Texaco, Occidental Petroleum, and some other long-term buyers were threatening to terminate their contracts unless BNOC immediately reduced its official price. At the same time, Saudi diplomats were running around to British government offices all over London, frantically insisting that BNOC had to stand firm. The Saudis feared that if BNOC lowered its official price, Nigeria would quickly follow suit, setting off a severe downward spiral. In their worst nightmare they could see just such a spiral leading to the collapse of the world oil market and, heaven forbid, the end of OPEC.

Darracott and his colleagues were caught between the proverbial rock and hard place. On the one hand, given the political pressure to maintain the flow of oil revenues into a national economy besieged by high government deficits, BNOC couldn’t afford to make a major price cut. On the other hand, $30 a barrel was dangerously close to being too high for the glutted marketplace. BNOC simply had to play it cool and appeal to its customers’ sense of fair play. In January 1983 BNOC had cut the price of Brent 50 cents to the current $30 level, but when spot market prices rose higher than that in the fall, the company had resisted the temptation to rescind the price cut. Now BNOC executives reminded their customers of that action.

That’s why Darracott kept rechecking the numbers on his video screen as he placed calls to customers and suppliers. Although it was already late afternoon in London, it was midmorning in New York and oil futures trading had just opened on the New York Mercantile Exchange. The oil futures market is a recent addition to the commodities exchanges. While it doesn’t have the cachet of the spot market—for one thing, only one of the world’s forty major crudes is traded—it has become a useful tool in the industry. Major oil companies play it to hedge their bets on the spot market, and executives like Darracott keep track of it to get a sense of the market. The contracts offered on the Merc were based on West Texas Intermediate (WTI), a crude produced mainly in the Permian Basin. The WTI price was of special interest to Darracott because the spot market price for Brent and the futures price for WTI normally fluctuate in tandem. As a rule, WTI usually sells for 50 cents to $1 per barrel more than Brent.

Darracott was pleased to see that prices for WTI were holding up fairly well. Friday morning futures trading in New York had opened at $29.13 for January contracts and $28.31 for March. When those quotes were translated into Brent prices, they came out at about $29.88 and $29.06—not great but still a good 50 cents above the yearly lows for the two contracts.

Then a startling news item flashed across the financial wires. Citgo Petroleum Company, the large Tulsa-based independent, had just slashed the posted price it would pay for WTI from $30 a barrel to $28.50. Citgo justified its unexpected decision by pointing to the continuing decline in U.S. oil consumption and the world oil glut.

The market’s reaction was immediate. As the prices posted on his video screen began to tumble, all Darracott could do was stare in dismay

Loops in a Chain of Traders

By early afternoon New York time, as futures prices for WTI fell more than 50 cents per barrel on the Mercantile Exchange, the word was on the street that Vin Boemio wanted to buy a cargo of North Sea crude on the spot market. Boemio’s staff had located two firms willing to sell at about $28 a barrel, which would cost Bomar $14 million. But Boemio’s friend at First National Oil Brokers had phoned in with an even better offer.

“I’ve got a seller at $27.95,” the broker told Boemio.

“Offer him $27.90,” Boemio instructed, “and get back to me right away.” That would bring Bomar’s cost down to $13.95 million.

A few moments later, the broker called Boemio back to let him know that the anonymous seller was ready to accept his counteroffer.

“Can you bring him in firm so I know the guy’s for real?” Boemio asked.

Although Boemio trusted his broker, he always acted cautiously when dealing with unknown sellers. If Boemio wasted time trying to make an unrealistic deal at less than $28 a barrel, he might miss out on the higher-priced but surer deals his staff already had lined up.

“There’s no problem,” the broker replied. “The seller is someone we deal with all the time.”

“Okay,” said Boemio, after reviewing the specifics of the contract with the broker. “It looks like we’ve got a deal.”

Later that day, Boemio learned that the seller was Flyg, after which the transaction was wrapped up quickly. Flyg composed a telex message outlining the terms of the deal: the price ($27.90 a barrel), the type of crude (Brent), the size of the cargo (500,000 barrels plus or minus 5 per cent, at the buyer’s option), and the month in which the oil would be shipped (March). Boemio replied with a telex confirming Bomar’s agreement to the transaction. In the coming weeks the two parties would exchange formal contracts by mail. But both Boemio and Flyg regarded those documents as anticlimactic. The ethics of the business bound them to their telex agreements.

The Vitol-Bomar deal was a trade between two trading companies, which meant that both buyer and seller were betting on the come. Vitol was now obliged to provide Bomar with oil it didn’t have—at least not yet—within a specified time period at a specific price. To make good on that commitment, Vitol would have to cover itself by purchasing an equivalent volume of Brent on the spot market—after the price had gone down. Because Bomar didn’t own a refinery or have an agreement with anyone to refine its crude, it would have to sell the cargo to someone else—preferably before the oil was loaded onto a tanker but, at the very latest, before the tanker arrived at a discharge port. Otherwise Bomar would be stuck with what’s called a distressed cargo and would probably lose money on the deal. Whether Bomar and Vitol came out ahead depended entirely on what the market did over the next few days or weeks.

Neither Vitol nor Bomar knew what producer would supply the oil they had just traded or what tanker it would be on or even exactly how much North Sea oil would be available for the spot market. (In the case at hand, about thirty cargoes of March Brent ended up on the spot.) The typical spot market contract stipulated only that the crude would be picked up, or “lifted,” in March and that the traders would have fifteen days’ notice of that event. More precise information would not be available until mid-February, when Shell Expro, the Brent pipeline operator, would announce its lifting schedule for the following month. Only then would the telex transactions assume a physical reality, for then companies would be matched with cargoes.

In the meantime, Vitol and Bomar would be dealing in an “undated” March cargo. In the parlance of the fraternity, they were trading “dry” barrels as opposed to “wet” barrels. Trading dry barrels wasn’t merely a game of paper transactions. Each cargo of dry barrels would become a cargo of wet barrels when the lifting dates for March were announced. Eventually the oil would have to be bought from a North Sea producer and sold to a refiner or to a trader who could get it refined. In the interim, however, the cargo could be bought and sold an almost unlimited number of times. Indeed, by the time most cargoes become wet barrels, they have been owned by anywhere from five to forty companies in a chain of transactions. Usually a trader holds on to a spot market cargo for less than 48 hours before passing it along to another firm.

A trader never knows who else is a part of his particular chain—other than the companies he bought from and sold to—until the lifting dates are announced. Then things can really get tight. With the announcement of the monthly lifting schedule, the operations people at the trading companies begin tracing the links in the chain in both directions. If the chain starts with a producer and ends with someone who can get the crude refined, the trading companies in the middle are more or less home free as far as their delivery obligations are concerned. But if the chain begins or ends with companies that are simply trading crude, then those companies can find themselves with only two to six weeks to make a deal. Sometimes, if there is trouble at one end of the chain, it can cause problems for everybody.

Although every chain has its winners and losers, it is sometimes difficult to tell them apart, because trading in a specific type of crude is always part of a larger, secret strategy. The purchase of one type of crude might be made as a hedge against the sale of another type or a position on the futures market. A cargo of Brent coming out of the North Sea might be exchanged for a cargo of WTI at a price differential. A company may go long one day to disguise its intention of selling short the following day. As a result, the longer chains often contain several internal loops in which companies buy one week and sell the next, only to buy and sell the same cargo several weeks later.

Such was the case with the Vitol-Bomar deal. At face value the trade appeared to be a model pairing of a short with a long. In fact, the March Brent deal between Vitol and Bomar was only a part of their larger trading strategies. Bomar had a contract giving it the option of selling one cargo of Brent per month to Ultramar, a British producer, refiner, and marketer, at 10 cents a barrel below the official price. Bomar was buying from Vitol at $27.90 with the intention of turning around and selling it to Ultramar at $29.90. That same afternoon, Boemio exercised that option and, in so doing, showed again his bullish leanings. If BNOC held firm to its official price until March, Bomar stood to make $1 million on the deal, an unusually high profit in a tight market. But if BNOC lowered its price, then Bomar’s profit margin would likewise shrink; and if the official price went low enough, Boemio might lose money on the transaction.

Flyg, meanwhile, was adroitly hedging his bet on the spot market by playing the “crack spread” on the futures market. The crack spread gets its name from the catalytic cracking units that refine crude into gasoline and heating oil. The spread is the difference between the price of crude and the price of refined products. When the crack spread is wide, most traders buy long on low-priced crude and sell short on high-priced refined products like heating oil. They are betting that the crack will narrow—that they will make money because crude prices will rise or heating-oil prices will drop. When the crack spread gets too narrow, traders short crude and buy heating oil in hopes that the demand for heating oil will rise faster than the demand for crude. “Richard Flyg is a master of the crack spread,” attests one broker.

Although Flyg refused to discuss his hedge, sources familiar with the transactions say he probably balanced the Bomar sale with the purchase of equivalent futures contracts in heating oil or another refined product. At a going price of around 74 cents a gallon, his investment in heating-oil futures would have been about $31.08 a barrel, a low price. By selling crude due for lifting in March, he left himself plenty of time to cover his obligation to Bomar, hopefully at a lower price. But even if that didn’t happen, his reading of the spread told him he would probably make money at the heating-oil end of the equation.

The Man Who Stiffed the Russians

Boemio and his staff knew that John Deuss would become a major presence in the market for March barrels of Brent, but they didn’t know when or where. Deuss has his official headquarters in Bermuda. His biggest office is in Houston, and he’s got outposts in Geneva, London, Tokyo, Rio, New York, Los Angeles, and Cape Town. But Deuss, a short, frenetic man who reportedly speaks half a dozen languages, doesn’t spend much time in any one place. Rather, he’s almost constantly flying between places, sometimes in the company of his tennis pro and his martial arts instructor—eating, sleeping, and doing deals from the telephone-equipped cabin of his company’s private jet. His company is Transworld Oil (TWO). Although TWO executives refused to be interviewed, reliable industry sources confirm that TWO, with its sixty cargoes a month and $8 billion in annual volume, is more active on the spot market than any of the Seven Sisters or the major independents.

In addition to being one of the biggest international oil traders, Deuss is also one of the most controversial. He comes from the Dutch hamlet of Berg-en-Dal, and he began his career as a products trader in the mid-sixties. His first big deal involved the purchase of a cargo of Egyptian kerosene from Jacques Detiger, which he parlayed into a huge profit. Since that time, the bigness and boldness of Deuss’ exploits have led many traders to compare him to the notorious Marc Rich. While Deuss has not been accused of tax fraud or any other criminal wrongdoing, he is definitely persona non grata in the Soviet Union and some European circles.

Much of Deuss’ reputation stems from the time he walked on a deal with the Russians. In the mid-seventies Deuss signed a long-term contract to buy Urals crude under the name of JOC Oil and arranged to sell it to various European refiners. But he encountered what a source familiar with the deal later described as “major problems with the way the Russians performed on the contract,” including alleged shortages in oil volumes, late deliveries, and failures to deliver. Shortly before the 1979 Iranian crisis, Deuss stopped payment on a $20 million cargo, citing the Russians’ nonperformance. When the Soviet Union tried to collect anyway, the bank backing JOC Oil’s letter of credit refused to release the funds. It didn’t hurt that Deuss had close ties to the owners of the bank.

After his break with the Russians, Deuss folded JOC Oil; the repercussions of the dispute had caused it severe financial problems. But he started up again under the banner of Transworld Oil and immediately got into the most dangerous game of all—supplying oil to South Africa in defiance of the OPEC boycott. Deuss gained entrée into the South African market because Marc Rich, the market’s traditional supplier, had neglected the area after expanding into the United States. Today Deuss employs fifty traders worldwide, a third of whom are based in Houston. Most other Houston concerns have offices in Greenway Plaza or near the Galleria, but Deuss—iconoclast to the end—located his offices out by Intercontinental Airport. In theory, the Houston office reports to the New York office and to company headquarters in Bermuda. In practice, all of TWO’s oil traders answer to John Deuss himself.

In the week following the Vitol-Bomar deal for March Brent, TWO appeared to be staying out of the trading. It was still early—and besides, it was getting increasingly difficult to read the market. Following the Citgo price cut, Egypt and the Soviet Union announced similar reductions. At the same time, there were some fresh signs of bullishness in the U.S. The American Petroleum Institute’s last pre-Christmas statistical bulletin showed that domestic stocks of both crude and heating oil were below the ninety-day supply level. All it would take was the long-awaited coming of winter to spur the U.S. energy demand. But industry sources say that Deuss had another reason for standing pat. In the previous few months, TWO had taken some long positions in spot market crude and was getting hammered. For the moment at least, Deuss apparently didn’t want to risk any more money in the market.

With TWO temporarily disengaged, Boemio made his next move in the March Brent play. He sold two cargoes at $28.25 and $28. Though these sales may appear to be a reversal of his previous bullish position, he says they were not. They were hedges against long purchases of WTI futures contracts he had made on the commodities exchange. What he was doing with WTI was exactly analogous to what Flyg had done with heating oil; he was betting on the spread. Normally the difference between the price of WTI and the price of Brent is about 75 cents. At the moment it was about half that. Though still bullish on Brent in the long run, Boemio believed that the price of WTI would rise faster and that he could make a little money by playing the exchange. “We figured the spread on the Merc was too narrow,” Boemio later explained. “We were gambling that it would have to widen in the future.” As indeed it did. “The market always corrects itself,” said Boemio with a sly grin.

Then, on Thursday, December 22, just as most New York–area traders were preparing to leave town for the holidays, winter swept in with a vengeance. A massive arctic cold front descended upon the U.S., producing no fewer than six hundred record lows across the country. In addition to fulfilling dreams of a white Christmas across the Northeast and the Midwest, the cold spell brought with it a lot of burst pipes along the Gulf Coast—not only in homes but also in oil refineries. Many refiners who had already let their stocks dwindle were forced to cut back to less than half capacity, and some had to shut facilities down completely.

The following Tuesday, December 27, the Merc reopened with a roar. March futures contracts for WTI traded as high as $30 a barrel and eventually closed at $29.88, up 42 cents for the day. January heating-oil contracts soared. The next day Citgo reversed itself and retroactively restored its posted price for WTI to $30 a barrel. By that time spot market prices for March cargoes of Brent were selling at a new high of $29.50. Though still 50 cents below the BNOC price, spot prices were closer to the official level than they had been in nearly four months. It looked as if Darracott and his colleagues might be able to defend BNOC’s stay-firm stance for 1984 after all.

When trading resumed in the first week of 1984, the market was still behaving quixotically. The Nigerian government fell, and so did crude-oil futures. Then the price bounced back, stabilizing just above $29 as word spread that the new military regime in Nigeria didn’t intend to break ranks with OPEC. In London BNOC faced renewed opposition to its $30 official price from Oxy, Socal, and Texaco. While BNOC continued to dicker, market logs show that Oxy turned to the spot market, purchasing a 500,000-barrel cargo of March Brent from Houston-based Acorn at $28.80, thereby saving $1.20 per barrel, or $600,000 on the total cargo, against the official price.

Into this new wave of market uncertainty jumped John Deuss. On January 10 TWO bought a single cargo of March Brent at $28.95. Fittingly enough, the seller was its leading rival, Phibro Energy. Phibro is the oil trading division of Phibro-Saloman, the $30-billion-a-year commodities-trading and investment-banking conglomerate. Phibro is also the oil trading industry’s most prolific training ground. Not only did both Marc Rich and his partner, Pincus “Pinkie” Green, learn their trade at Phibro but Boemio and a raft of other traders did as well.

Phibro offers a graphic illustration of how the importance of oil often overrides politics and ideology. It was started by German Jewish immigrants, and its largest stockholder is a South African. But because of Phibro’s size, these well-known facts don’t prevent the company from dealing with OPEC producers. With revenues of $18 billion a year from a variety of energy-related interests, Phibro is the only trading house whose presence on the spot market may exceed that of TWO.

The Transworld-Phibro trade put the two giants on opposite sides of the market. Phibro, which had sold another cargo of March Brent for $29.30 in late December, appeared to be going short by a million barrels. TWO, which subsequently proceeded to buy a trio of February, March, and April cargoes from Sun for $29.01, appeared to be going long on Brent to the tune of at least two million barrels. If prices continued to rise, TWO could be the big winner and Phibro the big loser. But if prices fell, TWO would take the hit and Phibro would come out on top, at least in theory. Either way, the confrontation between them would reflect the overall trend in the market.

If there was a trend, though, it was hard to see. There were blizzards in the Northeast and the Midwest. The spot price of Brent jumped to $29.70. News leaked out that Saudi Arabia was stockpiling 50 million barrels of oil on tankers moored safely outside the Persian Gulf. This information confused traders—did it mean the Iran-Iraq war was escalating or did it mean the glut was getting worse?—and the price fell. In mid-February another cold front swept across America and sent the spot price over the official $30 price for the first time in four months. Then there were reports that Iraq was accelerating its war against Iran, which should have driven prices up even further. Instead, the spot price slid back down to $29.90. On March 1 even Marc Rich apparently got a piece of the action, buying a cargo of March Brent through a Japanese intermediary and paying $29.97. And four days after that, as Boemio put it, “the market went nuts.”

Suddenly, it seemed, everybody wanted Brent no matter what the price. When the dust had settled, it looked like the biggest buyer was Sun, a Pennsylvania-based producer and refiner with a chain of gas stations in the Northeast and the Midwest. Between March 5 and March 12, logs show that Sun purchased at least four cargoes of Brent, or roughly two million barrels, at prices ranging from $29.90 to $31. The sellers during this period included both TWO and Phibro, which liquidated two of their March cargoes at $30.05 and $30 even.

Sun’s buying spree marked the end of spot market trading in cargoes of March Brent. Because of the way the contracts were drawn up, the effective monthly deadline for nonrefiners was March 13, which is when cargoes began to be shipped. Although cargoes can be traded after shipping begins, a trading company in possession of a distressed cargo is not in the best of bargaining positions. If prices are steadily rising, there may be times when it is in a trader’s best interest to hold on to a distressed cargo for as long as possible. But not often. Like a rider who keeps a taxi waiting with its meter running, the owner of the cargo has to pay the vessel owners a demurrage charge of at least $3000 a day for each day the ship is anchored outside a port of entry awaiting delivery orders.

Who won in the March Brent trading? Who lost? It is impossible to say for sure. Traders don’t even tell each other information like that—after all, no poker player shows his cards after the hand is over. Take Richard Flyg and Vitol, for instance. Confidential market logs show that Flyg had a buy order for $28.45 matched against the cargo he sold to Bomar for $27.90. All things being equal, that would mean a loss of $275,000 for Vitol. But Flyg says that all things were not equal, that because of futures positions that he took on the Merc, he ended up making money. In the battle of the giants the market clearly went TWO’s way. According to some logs—and other logs may disagree—TWO traded nine cargoes of March Brent and Phibro traded ten. If the logs are read narrowly, it would appear that TWO made at least $485,000 on those transactions. Logs cannot be read that way, however, for they do not reflect all transactions or show the company’s larger strategies, which may increase or offset that profit.

As for Vin Boemio and Bomar, they did quite well in the March trading, thank you. Boemio’s bullishness got him into a little trouble in late January, when he had to scramble to break even on a trade after guessing wrong about the market’s response to the Saudi stockpile. (He had guessed that the price would go up, but it went down.) Then, after buying a cargo from TWO in anticipation of a quick price rise, he guessed wrong again. This time he wound up having to sell at a 60-cents-a-barrel loss, which cost Bomar $300,000. Still, because BNOC had held firm, he had cleaned up on the buy from Vitol (and the subsequent sale to Ultramar), and he had also done well in hedging on the futures market. Bomar wound up making about $1.3 million on March Brent.

The end of the spot market trading in March Brent was not, as any oil trader knew, the end of the story. Payment would not flow through the chain until thirty days after that cargo was actually picked up by a tanker in the North Sea. A lot could happen in those thirty days.

The Chain Breaks

The Viking Eagle docked at Sullom Voe on the windy afternoon of March 20 with the routine ease of a Cadillac pulling into a local filling station. The 750-foot vessel sported a bright-orange hull and a Singapore registration, but her owners were Norwegian and her captain was a voluble Filipino named Ernesto G. Bagaipo, dressed Eskimo style in a hooded anorak. By the time the Viking Eagle took on her cargo of crude, she would weigh more than 95,000 tons, the equivalent of 57,000 Cadillacs.

“Sullom Voe” is a name derived from the Norse and means “a place in the sun,” but the brown, treeless hillsides surrounding the harbor attest to a harsh climate. Officially a part of Scotland, Sullom Voe is located six degrees of latitude below the Arctic Circle, on the northeastern shore of the largest of the Shetland Islands. But it is slightly closer to Bergen, Norway, 190 miles across the North Sea, than to the bustling Scottish oil capital of Aberdeen.

The Viking Eagle was there to pick up a cargo of crude at a terminal operated by British Petroleum. Next to the peat bogs, the pint-size ponies, and the crumbling stone crofters’ houses that typify the Shetlands’ heritage, BP’s ultramodern terminal look both out of place and out of time. The $2 billion facility, a joint venture involving about thirty major North Sea producers, occupies one thousand acres. It has sixteen crude-oil storage tanks that can hold up to 9.6 million barrels, a daily throughput capacity of 1.4 million barrels, and two 100-mile-long pipelines that connect it to the North Sea production platforms. Once a tanker like the Viking Eagle arrives at Sullom Voe, it takes around thirty hours to fill it up and turn it around.

For practical and commercial reasons, no tanker ever loads precisely 500,000 barrels of oil. Purchase contracts always include a variance of plus or minus 5 per cent, so the buyer has the option of requesting as little as 475,000 barrels or as much as 525,000 barrels. But no matter what the request, the bill of lading never comes out in nice round numbers. The limitations of the equipment do not permit the volume to be measured out with the exactitude of a filling-station pump.

When the Viking Eagle left Sullom Voe on March 21, her cargo tanks carried an estimated 520,312 net barrels of crude bound for the Delaware River port of Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania. The producer of this cargo was Shell (U.K.), and the buyer—and refiner—was Sun. In between, the cargo’s chain of owners had included BNOC, Bomar, Ultramar, Sohio, Phibro, TWO, and a dozen others. The voyage from the North Sea across the Atlantic took twelve days. Along the way the Viking Eagle had to battle rough seas, high winds, and the generally foul weather characteristic of the season. But on April 3 she arrived safely in Marcus Hook and docked at a berth adjacent to the Sun refinery.

Although Sun had chartered the Viking Eagle to transport the cargo from the North Sea, the bill of lading—the actual title to the crude—still read “To Order of BNOC,” which was the second link in the chain, after the original producer. But that was a small problem and not unusual. When spot market cargoes involve more than two or three companies, the names on their bills of lading often don’t match their destinations. Eventually, Sun would have to get a bill of lading signed by all the companies in the chain of title. But to ease delivery of the crude while the paperwork caught up with them, Captain Bagaipo accepted a letter of indemnity from Sun protecting the Viking Eagle from charges of misdelivery. Then the ship set off on a return trip to Sullom Voe.

Payment for the cargo was supposed to be made on April 20, thirty days after the oil had been loaded at Sullom Voe. But on that very day, Charter—one of the companies in the chain—filed for bankruptcy in federal court in Jacksonville, Florida. The Charter bankruptcy stopped the flow of payment on the March cargo in midstream. First Phibro decided to withhold the money it owed Charter. Then Charter withheld payment from Pegasus Petroleum, the company from which it had bought the cargo. But Pegasus’ bank nevertheless proceeded to pay on a letter of credit that Pegasus had put up to purchase the cargo from Occidental. That left Pegasus and its bank some $15.5 million in the hole and forced Pegasus to sue for the missing payment from Charter.

What did all this have to do with the Viking Eagle? Plenty. When the ship returned to Marcus Hook on May 1 with a second cargo of crude bound for the Sun refinery, federal marshals seized the vessel on behalf of Pegasus and its bank. The Viking Eagle‘s management had played no part in, and in fact didn’t even know about, Phibro’s decision to withhold its payment from Charter or Charter’s decision to withhold its payment from Pegasus, but admiralty law holds shipowners responsible for the cargoes they deliver. Although the marshals allowed the Viking Eagle to discharge her latest oil shipment, they ordered the vessel to remain at anchor until the dispute with Pegasus could be resolved. In a cold sweat, the Viking Eagle’s management asked Sun, one of its best charter customers, to make good on its letter of indemnity.

On the day the Viking Eagle was seized, the gasoline refined from her first March cargo was sitting in storage tanks as part of Sun’s refined-product inventory. Most of it would be shipped in late May to Sunoco stations and various independent outlets in the East and Midwest. The average Sunoco station sells about 50,000 gallons of gasoline per month and turns over its inventories about every two weeks. By the third week in June, almost all of the gasoline lifted in crude-oil form from the North Sea back in March had been consumed.

Even then, though, the oil trading community was not through haggling over March Brent. For the Viking Eagle and its owners, everything had ended happily ever after. On May 3, two days after the vessel had been seized, Pegasus agreed to accept Sun’s letter of indemnity. But for Bomar and some of the other companies along the chain, the ending was not so happy. Following the release of the Viking Eagle another round of legal problems cropped up—namely, companies starting suing each other. Pegasus, Phibro, and Charter still had to resolve their payment dispute. And lawsuits filed in Houston and New York involved not only those three protagonists but also other companies up and down the chain. Although the oil is long gone, those lawsuits remain today.

Afraid of Peace

The future of the world is on the spot. Since February at least forty ships of various nationalities have been attacked by Iran and Iraq in the Persian Gulf, and by late summer half that number had been damaged by underwater explosions in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Suez. But so far the conflagrations in the Mideast have not led to another energy crisis. Instead, the oil glut has continued, and so have the good times at the local gas pump. By late August, spot market prices of Brent had fallen from the spring peak of $31 to less than $29. Retail gasoline prices in the U.S. had dipped to $1.23 per gallon, 6 cents lower than those of the year before.

Given America’s increasing dependence on non-OPEC producers like Mexico and Britain, Vin Boemio and other traders now seem to fear an outbreak of peace in the Persian Gulf more than they fear an escalation of the war. Iraq’s production has dropped to zero. Iran is at one third of its capacity. A return to full production by the two combatants could swell the current glut into a flood of biblical proportions, drowning both OPEC and non-OPEC producers in an undertow of downward spiraling crude prices.

In the meantime, the volume of oil traded on the spot market keeps growing. New York Mercantile Exchange chairman Michel D. Marks says that the spot market now accounts for 40 per cent of the world’s oil transactions. He predicts that by the end of the decade, 90 per cent of the world’s oil trades will be on the spot, reversing the ratio between long-term and short-term contracts that prevailed before the Arab embargo. As Marks points out, the abundance of foreign crude and the expense of stockpiling inventories lead refiners to rely on the spot market as much as possible.

Is this good or bad? A case can be made either way. Certainly as long as the oil market is glutted, the spot market keeps the producing nations from doing anything rash. None of them can arbitrarily raise prices when there are obvious alternative sources of supplies. But the glut won’t last forever, and when it ends, the growing reliance on the spot market may make consuming countries even more vulnerable to a future crisis in the Persian Gulf. Instead of being able to count on a fixed price for their supplies, refiners will have to buy their crude on the spot at prices significantly higher than official levels. Even that cloud has a silver lining, though. The spot market isn’t a cartel; it’s a market, where prices are set not by a handful of OPEC ministers but by market conditions. When conditions dictate that prices drop once again, they will drop.

Like the spot market price, the fates of the men who traded March cargoes of Brent have swung up and down. Colin Darracott enjoyed a pleasant spring as the spot price surged above $30. Now, with spot prices back down, he is again faced with the prospect of having to defend BNOC’s official price against customer pressure for a reduction. But at least he can rely on the British government to keep BNOC in business. Several private-sector companies who traded March Brent, most notably Charter, have folded. Although Transworld Oil has reportedly been bloodied by the summer price slump, John Deuss still circles the globe, making his presence felt by taking bold long positions in crude. Phibro-Salomon has considered and rejected a corporate divorce, but Phibro Energy is quietly and profitably continuing to trade high volumes of crude on the spot market. Richard Flyg is still cautiously hedging Vitol’s bets by playing the crack spread and still making money for his boss, Jacques Detiger.

Vin Boemio is still a bull, but now he’s looking for new pastures. Last spring he resigned from Bomar, citing personality conflicts. He is now weighing offers from various U.S. companies to start up oil trading subsidiaries. Boemio intends to get back into the market and ride out the glut, confident that the good old days of the late seventies will return. “Sooner or later, the spot market’s got to make a comeback,” he avers. “I just want to be there when it happens.”

The King Is Dead

How the spot market beat mighty OPEC, in ten easy steps.

There’s a saying that oilmen are like cats—you can never tell from the sound of things whether they are fighting or making love. It’s an accurate description of the relationship between OPEC and the spot market. In one sense they’re unrelenting adversaries, rivals for control of the oil world. But in another sense they’re loving every minute of it. Both are incomparably better off than they were in the good old days of the fifties and sixties, when first the Texas Railroad Commission and then the Seven Sisters kept the price of oil under $4 a barrel. The reign of OPEC began with the 1973 embargo. Here, step by step, is how the era of OPEC ended—and the era of the spot market, when only fools get locked into long-term OPEC contracts, began.

1973 OPEC Embargoes Oil. The cartel sows the seeds of its own destruction. By ripping up long-term contracts and imposing its own prices, OPEC establishes that the contracts aren’t worth the paper they are written on. The precedent set in a time of shortage will come home to haunt OPEC in a time of glut, when OPEC’s contracts will be ripped up.

1974 South Africa Is Singled Out. When OPEC lifts the ban on oil shipments to the West, South Africa remains under the embargo. Oil traders, who during the embargo increased their share of the market from 1 per cent to 15 per cent, have a big reason to stay in business. Marc Rich becomes South Africa’s chief supplier, and the cult of the shadowy oil trader is born.

1975 The North Sea Comes On-line. OPEC’s high prices make drilling in the rough waters of the North Sea economically feasible. By the end of the year, two prolific fields are producing, and Western Europe is no longer just a helpless OPEC pawn. Eventually North Sea producers will undercut OPEC prices, forcing the cartel to respond with cuts of its own.

1976 U.S. Regulation Bombs Out. Oil companies maneuver to take advantage of Congress’ distinction between old (controlled) oil and new (uncontrolled) oil. Overnight a new breed of trader, skilled at getting around the regulations, arises. Companies learn to use the spot market to jack up their profits; terms like “daisy chain” enter the oil vocabulary.

1977 GM Downsizes the Chevy. Since Detroit always reacts rather than acts, GM’s decision is proof that America has gotten serious about energy conservation. The reduced consumption of gasoline will become the biggest single contributor to the oil glut.

1979 The Shah Falls. The watershed moment. First, American policymakers lose their main incentive for propping up OPEC—namely, the Shah’s line that he alone can maintain stability in the Middle East and that he needs high oil prices to build his military machine. Second, postrevolution chaos reduces Iran’s output from 5.5 million barrels a day to none. Companies have to hustle to replace it. They turn to the spot market. Third, OPEC increases oil prices from $13 to $24, touching off the U.S. oil boom and making traders rich overnight, which naturally brings more traders into the market.

1980 The Japanese Invade. The swift response to OPEC’s greed is more conservation. Fuel-efficient imported cars take their biggest bite ever of the American market, up from 22 per cent to 27 per cent in one year.

1981 Reagan Decontrols Oil. The end of the old oil–new oil distinction is disastrous for small refiners and traders that had thrived under regulation. But it’s even worse for OPEC, as the oil boom leads to an oil glut. The winner is the spot market, as refiners scramble to find the best deal.

1982 Mexico Devalues the Peso. The straw that breaks OPEC’s back. Three months after the devaluation, non-OPEC-member Mexico is selling more oil to the U.S. than Saudi Arabia is. By 1984 Mexico is supplying 23 per cent of U.S. oil consumption, the Saudis only 9 per cent. Since Mexico doesn’t have nearly the bargaining power the Saudis had in 1973, the producing countries’ control over oil prices is unlikely to improve.

1983 Trading Goes Legit. When the New York Mercantile Exchange begins trading futures in West Texas Intermediate crude, the spot market becomes institutionalized. No longer does price information have to be gathered from the grapevine; now there is a market price to rival—and ridicule—OPEC’s fixed price. The cartel is broken.

- More About:

- Energy

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston