Debra Tice’s phone pinged at 4:30 a.m. on Monday, May 2, the 3,548th day since her son Austin had disappeared in Syria. Given the time difference between her home in southwest Houston and the Middle East, she was accustomed to receiving messages in the dead of night from sources and friends she’d gotten to know in the region. But this time the email came from Washington, D.C.: White House deputy national security adviser Jon Finer wanted to know if Debra and her husband, Marc, could meet with President Joe Biden in his office that afternoon.

Debra had returned to Texas just a few hours earlier, after a week of briefings in Washington on developments in her son’s case. But recent travel be damned: a chance to press the president on bringing their missing son safely home was not one the Tices were going to pass up. So Debra roused Marc, and they dashed to board a nonstop flight to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport. There, they were whisked directly to the White House by the FBI agent assigned to their son’s case and ushered into the Oval Office, where they took a seat on one of the two beige damask couches in the center of the room.

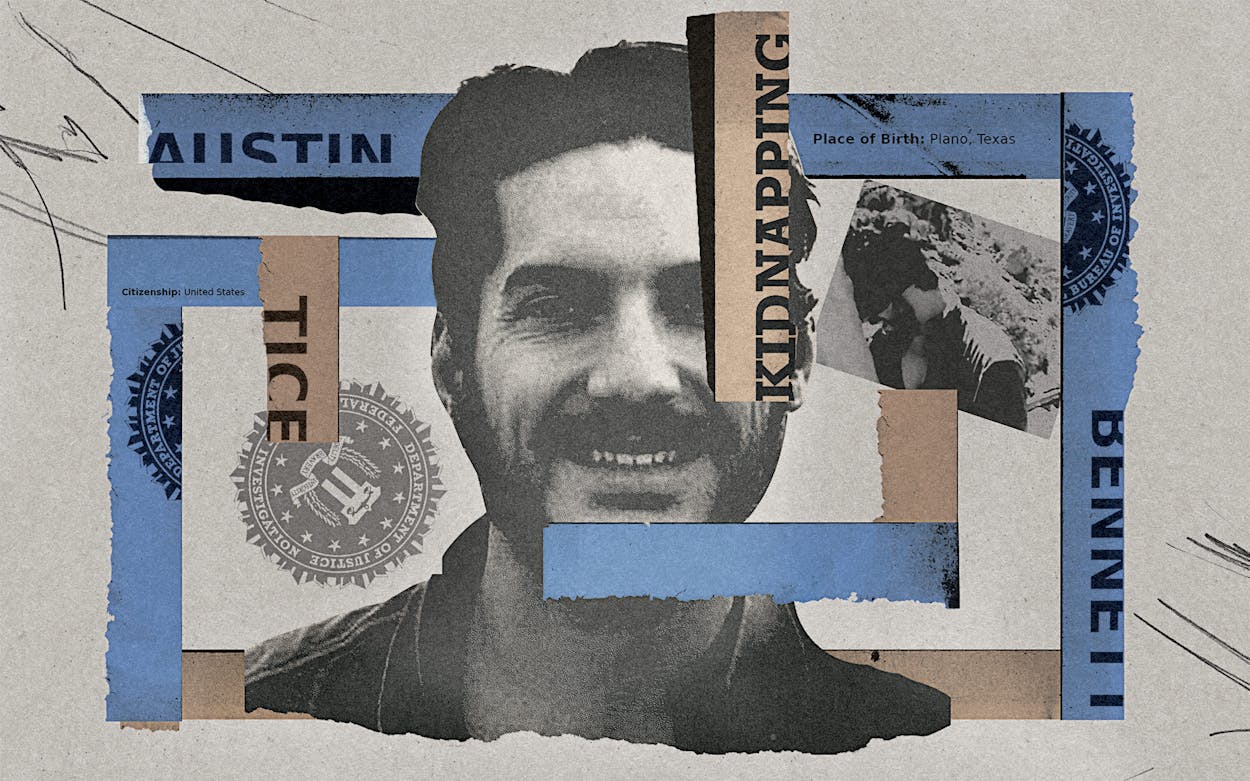

The president, who sat in a nearby armchair, was well versed in the particulars of Austin’s case. In 2012 the thirty-year-old second-year Georgetown University law student and former Marine Corps captain had decided to spend the summer reporting from Syria on the country’s civil war. In late May, he ducked under a fence along the Turkish-Syrian border and embedded with a group of Free Syrian Army rebels. Nine days later, despite his lack of formal journalism experience, Austin wrote his first dispatch for McClatchy, a publishing company that owns dozens of papers across the country. Soon, he was also stringing for the Washington Post and appearing on CBS News and BBC Radio. By August, after 83 intense days inside Syria, he decided to head to Beirut for a break.

On August 14, while bound for the Lebanese border by car, he was detained in a government-controlled area. It was near the southeastern Damascus suburb of Daraya—a hotbed of protests where, the following week, regime forces would massacre some four hundred rebels and civilians. Within a few days, a tipster walked into the Czech embassy in the country (the U.S. embassy had suspended operations earlier that year) and informed Ambassador Eva Filipi that Austin had been arrested. His captors have never issued any demands.

Biden told the Tices he had reached out to officials from prior administrations about Austin’s case, then exchanged ideas with the family about what might help secure his release. The Tices were buoyed when, during the meeting, Biden instructed his National Security Council to engage directly with the Syrian government. “Listen to them, find out what they want, and work with them,” Biden said at least three times, in Debra’s recounting.

Soon Biden’s national security adviser Jake Sullivan and others in attendance exited the room, and the Tices had time alone with the president. What was intended to be a 15-minute meeting stretched to 45. As they prepared to leave, Biden brought up the “big Texas bear hug” Debra had offered him in sympathy at a June 2015 event with other hostage families during President Barack Obama’s tenure, less than a month after the then–vice president’s son Beau had died of brain cancer.

August 14, 2022, marks ten years of captivity in Syria for Austin, a particularly grim milestone for the longest-held American journalist in history and the only one currently a hostage. In those years, the only public clue about Austin’s whereabouts came in the form of a YouTube video uploaded five weeks after his disappearance, titled “Austin Tice still alive.” In the shaky 46-second clip, a blindfolded Austin is hurried up a rocky path on a scrubby hillside by a group of men clutching assault rifles. After reciting a prayer in Arabic, Austin sighs and adds, in breathless English, “Oh, Jesus. Oh, Jesus.”

Debra and Marc, a former business manager in the oil and gas sector, are convinced their son is still alive, and the U.S. government concurs with that assessment. Austin was rumored to have been spotted at a hospital in Damascus in 2016, being treated for dehydration, according to the New York Times. The intelligence community has concluded he is in the custody of the Assad regime in Syria—which denies holding him—or a group aligned with it. “We believe that it is within Bashar al-Assad’s power to free Austin,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in a statement on Austin’s fortieth birthday last year. Most of the details of Austin’s captivity remain a mystery to his parents. And what they do know they are unable to share, for fear of endangering their son.

A few days after their meeting with the president, the Tices flew back to Houston and hoped that Biden’s words would translate into swift government action. But over the years they’ve learned that things never seem to move quickly in Washington. “No matter how long I stay there, the minute my first step is taken toward the airport, I feel like Austin’s file is slowly being shelved in D.C. That’s not true; that is just my feeling. I do know they keep working,” Debra said, before Marc added, “But not at the pace we would like.”

As Austin’s captivity has spanned three presidencies, maintaining attention on his case has been a struggle. For a time starting in 2015, Clear Channel Outdoor, an advertising company with roots in San Antonio, underwrote five billboards around Houston featuring Austin’s photo, and the Newseum, a Washington museum dedicated to the history of the free press, hoisted a banner on its Pennsylvania Avenue facade. Austin’s captivity has outlasted those billboards, the banner, and even the museum, which closed in 2019.

His case has proven particularly thorny because the Syrian government does not acknowledge Austin as a detainee, and Syria and United States do not maintain formal diplomatic relations. Nonetheless, the Tices have worked relentlessly toward his release. Since November 2012, Marc and Debra have made at least eight trips to Beirut—just seventy miles northwest of Damascus—and have held press conferences and meetings there with whomever they can. They have their congressman, U.S. representative Al Green, on speed dial, and have been heartened by the time Senator John Cornyn and his staff have devoted to Austin’s dilemma. Along with a host of volunteers, they once canvased every other congressional office on Capitol Hill to garner support from lawmakers. Debra, a devout Catholic, even met with Pope Francis in Rome in June 2018.

“Where things start isn’t any indication where things are going to end . . . fortunately, this administration has two and a half years left.”

Debra, who has relocated for months at a time to Washington and to Damascus, has found herself caught between two worlds since Austin’s capture. She homeschooled him and his six younger siblings, and there is an enormous gulf between her former world of “diapers and spaghetti” and the anguished limbo she has been in for the past decade.

Debra first went to Syria in early 2014, traveling to Damascus in a taxi from Beirut and renting a room in a budget hotel that prior to the war had been popular with European tourists. By the time of her visit, most of the other guests were internally displaced persons, and some evenings she helped them practice their English. During the day, she would walk around the souk inside the walled old city, where she would hand out half-page flyers with her son’s photo and identifying information to grocery vendors. Other times she would visit the Apostolic Nunciature to Syria, a diplomatic post of the Holy See, where she would meet with the cardinal to pray and brainstorm over coffee. Or she’d stop by various government ministries, where she sought out any official who would see her to talk about her son.

While in Damascus, Debra employed what she dubs her “mosquito method”—daily phone calls to Syrian bureaucrats—until she finally got a message back from a high-ranking member of the Syrian government, who said, “I will not meet with the mother. Send a United States government official of appropriate title.” Such a meeting is what the Tices have pushed for since then. After she left Syria, she realized her trip had spanned 83 days—the exact amount of time Austin had spent free inside the country.

By the final year of Obama’s presidency, there had not been public movement on the case, but outgoing officials briefed the incoming Trump administration on it. Communication between the Tices and the government went cold for a bit. During presidential transitions “you really go into a dark period in regards to the ability to communicate with the government,” said William C. McCarren, the executive director of the National Press Club, who has worked closely with the Tices since 2018. “That dark period ends up being almost a year.”

In the early days of his administration, though, President Donald Trump made the return of American hostages a centerpiece of his foreign policy. In February 2017, Mike Pompeo, who was then CIA director, opened a back-channel discussion with Ali Mamlouk, then the director of Syria’s National Security Bureau, to discuss Austin. But those talks stopped after Assad’s forces used sarin in a rebel-controlled province that April, killing at least ninety, and the U.S. replied with a missile strike.

Trump’s subsequent efforts to engage with Assad personally were stymied by his staff. In his memoir, former national security adviser John Bolton wrote that Trump had a “constant desire” to call Assad directly about U.S. hostages in Syria, an impulse Bolton and Pompeo, who was then serving as Secretary of State, found “undesirable.” The president remained passionate about Austin’s case, however, appealing to the Syrian government directly during a White House coronavirus briefing in March 2020. As he discussed foreign detainees potentially contracting the virus, Trump said, “Syria, please work with us. We would appreciate you letting [Austin] out.”

A meeting between the Syrians and a high-level American official finally happened in the waning months of the Trump presidency. In August 2020, White House aide Kash Patel and special envoy for hostage affairs Roger Carstens were dispatched to Damascus to meet Mamlouk and try to negotiate for the release of Austin and Majd Kamalmaz, a Syrian American humanitarian detained since 2017. According to the pro-regime newspaper Al-Watan, Syrian officials made the withdrawal of all U.S. troops from the country a precondition for further talks. (Some nine hundred U.S. troops remain in northeastern Syria today, advising and assisting the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces there.) The talks did not yield progress, and Patel and Carstens returned to Washington.

But there was a bright spot, according to Lebanon’s general security chief, Abbas Ibrahim, who brokered and attended the meeting. “We were able to do something positive there,” he told me in a phone call this July. “I’m talking about a promise of proof of life.” He declined to discuss further details. “That’s how it works—step by step. In cases like this one we have to be very patient,” Ibrahim said.

Ibrahim has successfully won the release of other Americans detained in Syria and Iran in recent years and met Debra in Beirut on her first trip to the city. They have become close, texting often. He has pledged to her that he will not stop working on Austin’s case until it is closed. “She’s an amazing mother,” Ibrahim told me. “She strengthens us in this mission.”

After the 2020 election, movement on the case seemed to stall while the Biden administration formulated its Syria policy. In 2021 and 2022, the Tices had conference calls and meetings with Secretary of State Blinken and White House staff. The meeting with Biden came about after Steven Portnoy, then the president of the White House Correspondents’ Association, introduced Debra to the crowd of 2,600 gathered at the group’s annual dinner in April and raised the issue of Austin’s ongoing captivity. A few minutes later, when Biden took the podium, he slipped an off-script invitation to the Tices into his prepared remarks: “Mom, I’d like to meet you and Dad to talk about your son,” Biden said. Debra held back tears and prayed that this would finally be the meeting that made a difference for Austin.

The Tices found the Oval Office meeting encouraging as a first step. “The words are great. The words are well-spoken, but Austin needs action,” Debra told me. The Tices want the government to work with “unrelenting urgency” to free Austin. “It takes tenacity,” Marc told me. “Where things start isn’t any indication where things are going to end; you just have to keep after it, and that hasn’t happened in Austin’s case, but fortunately this administration has two and a half years left.”

The biggest challenge to securing Austin’s release during any presidency has been the foreign policy establishment’s hesitance to meet with Syrian officials and thereby give Assad’s government a veneer of legitimacy. Yet in July, Biden traveled to Jeddah to meet with Arab leaders including Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, who U.S. intelligence agencies believe ordered the murder and dismemberment of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi. “The attitude of the U.S. government about negotiating for Austin has been so difficult because the optics are so bad,” one Washington insider with detailed knowledge of Austin’s case said, “but we are now indicating that we will meet with anybody.”

By all available accounts, no meeting between the Biden administration and the Syrian regime had taken place as of press time. But Ibrahim, the Lebanese security chief, returned to D.C. in late May to meet with Biden’s special envoy for hostage affairs and other ranking officials. Ibrahim declined to elaborate on particulars of potential negotiations but said he feels like things are on the right track. “Syria is not refusing, but they have their own conditions. In cases like this, every piece of information has its own price. It’s how it works,” he said. “I believe that we can reach now what we couldn’t during Trump.”

This article originally appeared in the September 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Long Fight to Free Austin Tice.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Houston