What may be the state’s most unusual oil well sits wedged between a creek bottom and a field dotted with newly baled hay on the northern edge of South Texas brush country. Fresh paw prints reveal that a bobcat recently investigated the six-foot-tall wellhead before padding over to seven semitrailer-size yellow steel boxes, each of which can hold several thousand gallons of water. The industry calls these “frac tanks,” named for their role in the hydraulic fracturing of underground rock formations—a.k.a. “fracking”—that brought about the shale energy boom.

The bobcat, or any casual visitor, could be forgiven for thinking this was some ordinary well. A small Railroad Commission–mandated sign at the turnoff of the Medina County road that leads to it, roughly forty miles west of San Antonio, displays the well’s name and its unique American Petroleum Institute identification number. The musky aroma of hydrocarbons emanates from a refurbished five-hundred-horsepower pump bought secondhand from the Canadian oil fields.

“How you doing? Been busy?” asked Dustin Frazier one morning in August, sounding much like any other company man checking in with any other oil worker anywhere else in the state. A twenty-year veteran of oil fields, he has forearms inked with tattoos, and his shaved head was covered by a white Quidnet Energy hard hat.

“I’ve been runnin’ through my ass,” replied Jeff Fine, who wore a mud-and-oil-stained coverall and a red hard hat from his employer, Renegade Wireline Services. The American flags on the backs of his steel-toe work boots were so dirty that the red, white, and blue had dulled to three shades of brown. “I’ve been slick linin’. I’ve been perforatin’. Not getting home much.”

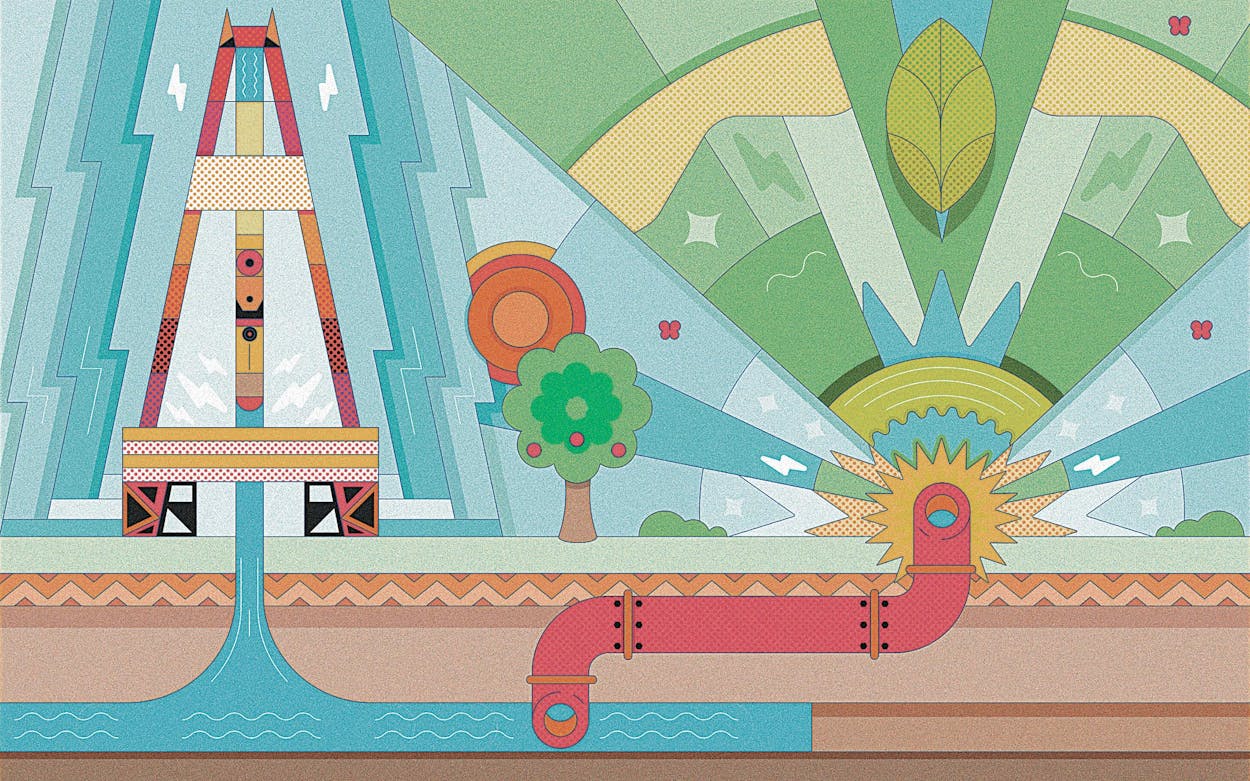

Putting to use the oil industry’s fracking know-how, Houston-based Quidnet is pumping water about 1,200 feet underground to split open the shale and other layers of rock that lie there. If all goes well, the force of the water compresses the rock surrounding it, which creates a gap of four centimeters into which water pools as a small reservoir. The well will then be closed, and the underground water will remain under the immense pressure of the weight of the earth—and of the pumps, frac tanks, bobcats, hay bales, and everything else above it. Later, Quidnet will open the well, releasing the pressure. The four-centimeter gap will narrow, forcing the water back up to the surface, where it will spin a turbine to generate electricity.

Quidnet represents a new breed of Texas start-ups that are tapping into the gusher of funding now available to clean energy companies. Their payrolls are stocked with veterans of the oil and gas industry who are leveraging the drilling and geological expertise born of the fracking revolution—hinting at a promising area of job growth in Texas. They’re deploying many of the same techniques and technologies used in fracking. They’re drawing upon the same supply chain and services used in fracking. But please, they implore you, don’t call them frackers.

Fracking is a dirty word to a significant number of Americans, and several states have banned the practice. The process has been linked to pollution of groundwater, leaking of greenhouse gases, and triggering of earthquakes, although the industry has taken some steps to mitigate these problems. A recent national poll by ClimateNexus found 41 percent of respondents were either somewhat or strongly opposed to using fracking to increase oil and gas supplies, while 42 percent were in favor. It’s understandable that Quidnet and others want to avoid the divisive label as they hope to scale up operations nationwide.

While its process similarly injects water through wells to break deeply buried rocks, what Quidnet does isn’t truly fracking. The company isn’t in the petroleum-extraction business. It doesn’t want to take oil and gas out of the ground, nor does it employ any of the chemicals and slickening agents common to frack jobs.

The Medina County site may look and smell like an oil well, and it is permitted like one by the state. But it is instead a geologic battery, using what’s known as pumped-storage hydropower. When water behind a dam is released to run through turbines, it generates electricity, and Quidnet aims to do something similar with its reservoirs deep underground. During periods of electricity surpluses when prices and demand are relatively low, such as temperate nights with stiff breezes powering wind turbines, the pressurized water can be pumped into the ground and stored. It can be tapped for energy later—for example, during hot summer afternoons—when it’s needed and will fetch an attractive price.

The son of a Texas wildcatter, Quidnet cofounder Howard Schmidt grew up around oil and gas. He studied chemistry and materials science at Rice University, and in the nineties he developed products and technologies that he sold to private companies and government agencies, including NASA. But he found himself drawn back into the energy business. He was boning up on fracking in 2008 when he saw a diagram of the process in a textbook and was struck by the idea that would turn into Quidnet: oil field techniques might be used to store water between layers of rock.

He filed a patent on the idea, then left for Saudi Arabia to work for its national oil company. While there, he ran studies to determine how water moved through the rocks of Ghawar, the world’s largest oil field, and for fun, he drove through the Empty Quarter, a dune-covered desert roughly the size of Texas. All the while, he kept thinking about his battery idea. It wasn’t rocket science, he said: “Our battery is literally rocks and water.”

Quidnet secured early funding from Breakthrough Energy Ventures, a climate fund seeded by Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, among other prominent investors, and set up headquarters in Houston in 2018. “Just like Silicon Valley is the home of a lot of tech start-ups, you go where the talent is, you go where the incumbent ecosystem is,” said Joe Zhou, the 32-year-old CEO of Quidnet. “For all things that we care about—for the drilling, for the data, for the know-how, for the entire technology-and-service suite—that’s in Houston.”

Zhou isn’t a Texan, but he grew up in what is possibly the most culturally Texan city north of the Red River: Calgary, Alberta. He is the son of engineers who migrated from China to Canada when he was ten. His parents got jobs working for Shell in the region’s oil sands refineries. “Country music, barbecue, and sprawl. That’s exactly what I’m used to,” he said.

Quidnet is refining its business plan and talking with utilities, energy traders, and others about commercializing its technology. Last year, it raised $20 million from investors, including the Geneva-based global commodity trading firm Trafigura, which is expanding into trading megawatts alongside oil barrels.

If the oil industry hadn’t spent billions developing new drilling technologies, Quidnet couldn’t have gotten off the ground. Only by piggybacking off this work has it come so far so fast.

In June, Quidnet announced a deal worth about $4 million with an independent agency funded by the Alberta provincial government to drill test wells. Another well is in central New York State, which has imposed a ban on fracking for petroleum. Quidnet’s first test well, in 2015, was in Erath County, southwest of Dallas. A jet of water from that well spun a turbine that generated about ten kilowatts of electricity, enough to run, on average, a few homes around a cul-de-sac. The company is aiming to develop wells that could deliver at least one hundred times more power, enough to keep the lights on in an entire subdivision for a few hours.

If the oil industry hadn’t spent the past few decades and billions of dollars studying rocks and developing new drilling technologies, Quidnet couldn’t have gotten off the ground. It was only by piggybacking off this work that it has been able to come as far and move as fast as it has. Aaron Mandell, a serial entrepreneur and another Quidnet cofounder, says clean energy companies should embrace their use of fracking technology. “People don’t like the f-word,” he said, “but in fact, fracking is key to a clean energy future.”

The geothermal industry is likewise looking to oil and gas as a source of new technology and ideas. At the forefront is Tim Latimer, the chief executive of Fervo Energy, another Houston start-up backed by Breakthrough Energy Ventures. His path to running a renewable energy business began near Cotulla, ninety miles southwest of San Antonio, a few months after he graduated from college in 2012. He was supervising a $15 million drilling rig for the Australian oil and mining company BHP Billiton in the Eagle Ford Shale. Barely old enough to order a beer on his off days, the eighth-generation Texan was responsible for completing some of the most complicated wells ever drilled in the state.

In certain places in the Eagle Ford, the temperature of the gas-bearing rocks can reach 300 degrees Fahrenheit, hot enough to cause problems for drilling equipment. Latimer started researching high-temperature drilling. Most of the papers he found on the subject came from the geothermal industry, which has been generating electricity from heat and steam brought up from deep in the earth for more than a century.

A 2006 report from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology posited that geothermal energy could become a ubiquitous resource if the industry could drill more productive wells at lower cost. It was a lightbulb moment for Latimer. The geothermal industry wasn’t keeping up with the innovations he was seeing in the Eagle Ford, where oil and gas companies were pouring money and brainpower into faster drilling of deeper, higher-yield wells.

Latimer quit his job and went back to school, earning master’s degrees in business and earth science at Stanford University. A couple years later, in 2018, he returned to Texas and started Fervo, a company dedicated to bringing modern drilling to the geothermal industry. Fervo began drilling its first wells this summer in Nevada, east of Lake Tahoe. The wells are deep, relative to others sunk by the geothermal industry—about two miles down, where the rock temperatures can reach 350 degrees. That’s about the same temperature as rocks in deep Haynesville Shale wells, in Louisiana and East Texas, where the oil industry developed technology to operate drill bits effectively amid challenging conditions. As it drills, Fervo uses oil field tools to collect a massive trove of data on the rocks, so it can improve its well designs.

Latimer expects the Fervo wells to be online next year. Water is pumped down into the rocks through one well, then pumped out through another once it is piping hot. At the surface, the water is converted to steam and run through turbines that Latimer says could generate about thirty megawatts of electricity, enough to power a small Texas town. Water is then returned underground, where heat from the earth’s core keeps the rocks perpetually hot.

From Nevada, Latimer hopes to drill many more wells—the same kind of scale-up operation that fracking companies got good at in the mid-aughts. He has some of the swagger of a wildcatter. “I started my career working at an upstream oil and gas company,” he said. “And in some ways, we built this company to be the twenty-first-century vision of that.” Helmerich & Payne, the Oklahoma-based drilling giant, shares his vision and has invested in Fervo, which altogether has raised more than $40 million.

Beyond Quidnet and Fervo, other companies are looking at ways to use the oil industry’s drilling and fracking techniques to develop new businesses belowground. Talos Energy, a Houston-based offshore oil producer, said in June that it was partnering with UK-based Storegga Geotechnologies to seek rock formations in which to store carbon dioxide onshore and in the Gulf of Mexico. “Every day I meet another oil and gas guy who is now a climate entrepreneur,” said Maynard Holt, the chief executive of Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co., an energy investment bank that made its name financing fracking deals. “I think there is going to be an explosion of clean energy activity out of the oil and gas sector, and we’ll be stunned in the next five to seven years . . . by how many of these problems are being handled by the oil and gas industry.”

Certain corners of the oil industry are already pivoting and finding ways to participate in the emerging clean energy economy. For instance, as Texas Monthly reported in May, a shipyard in Brownsville that once turned out $250 million jack-up rigs for drilling wells in shallow waters is now building an offshore construction vessel to install gigantic wind turbines in the Atlantic Ocean. The entrepreneurial embrace of renewable energy could create large numbers of jobs in Texas—from shipyards to drilling operations like Quidnet’s and Fervo’s. Yet it’s not clear if the new employment will match, in job numbers or salaries, existing petroleum payrolls.

Juliana Garaizar believes this migration to renewables is just beginning. The head of the Houston location of clean-tech incubator Greentown Labs, which opened in April, says 70 percent of the entrepreneurs she sees are coming from the oil industry. “We have the assets and infrastructure and the talent,” she said. “There has never been a concentration of engineers in the world bigger than Houston. People used to think about the energy transition as a problem, but now I think everyone is seeing climate change as an opportunity.”

As with most start-ups, it’s hard to predict which ones will flame out and which will massively scale up. These days, almost anyone with a promising idea can find funding. BloombergNEF estimates venture capital and private equity investments in the energy transition from fossil fuels to low-carbon technology totaled $5.9 billion in 2020, up 51 percent from a year earlier.

At the Medina County well, that investing trend was good news to Quidnet’s Dustin Frazier. After two decades in West Texas and Louisiana, he’d been looking for a change, yet something that was still familiar. “We got a well—we just use it for a different purpose. It is really the same thing, except you’re not dealing with oil and gas. It’s water,” he said. A few minutes later, he picked up a sledgehammer and took a swing at the connector between two joints, to loosen it. After a couple of blows, it budged. He finished opening it by hand, attached a hose to the well, and used the sledgehammer to tighten it up again. An oil field worker at Spindletop would have felt right at home.

This article originally appeared in the October 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Frack to the Future.” Subscribe today.