When George H.W. Bush started planning his funeral years ago, recalls Jim McGrath, his post-presidency spokesman, he made sure that members of the Texas press corps would be given priority access in the inevitable outpouring of international media coverage following his death.

“He just assumed he was going to take care of his hometown press and his home-state press,” says McGrath. “We decided that our priorities were Houston and the Texas media in that order.” The late president’s gracious accommodation to the Texas press corps in death reflects the kind of relationship that he had with the press in life. It now seems like a dreamy memory, particularly in an era when the current president derides the press as an enemy of the people.

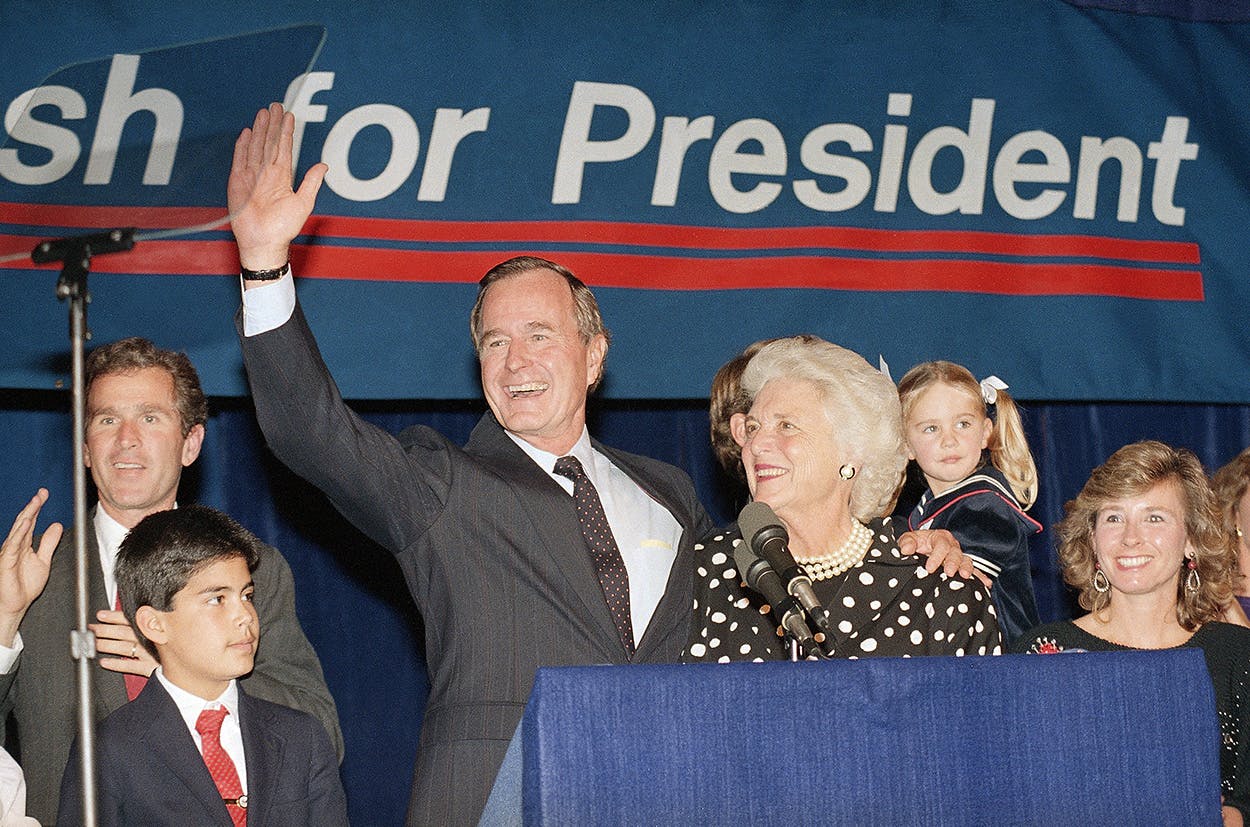

As a former Austin bureau chief for the now-defunct Dallas Times Herald and twenty-year Washington bureau chief for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, I covered Bush 41 from his first presidential race in 1980 through his eight years as vice president, four years as president, and into his post-presidency back in his hometown of Houston. I saw George H.W. Bush as did many of the other long-time reporters who followed him closely—both as a premier newsmaker who pioneered the rise of the Texas Republican party and as the approachable good guy eulogized in the flood of tributes following his death on November 30. I believe we covered Bush with unimpaired objectivity—and he certainly received his share of critical coverage—but the former president’s instincts for humor, friendliness, accessibility, goodwill, and acts of kindness created a rapport with the press that bears little resemblance to the contentiousness that exists in today’s political environment.

“He felt at ease with the press,” said Peter Roussel of Houston, a former White House spokesman who knew Bush for a half century and served as his official press representative during his years as a congressman, United Nations ambassador, and national chairman of the Republican party, as well as his 1970 campaign for the Senate. “Being his press secretary made it easy for me to be in that job because, quite frankly, he was his own best press secretary. He was his own best spokesman.”

Many of my own experiences with Bush came to mind as my wife Linda and I attended his funeral among more than a thousand other invited guests at St. Martin’s Episcopal Church in Houston. I remembered the white-knuckled ride on his speedboat off the coast of Kennebunkport, jogging with him during a two-day swing on the West Coast, and laughing over pizza with other Texas reporters at his office in Houston after he left the White House.

One of my most indelible memories is the time he rescued me from journalistic humiliation during the first year of his presidency. In November of 1989, as communist Eastern Europe was crumbling, Bush addressed hundreds of realtors at the Loews Anatole hotel in Dallas. Three of my Texas colleagues and I, part of a larger cluster of journalists covering the event from the back of a huge ballroom, were slated to interview Bush after the speech. The plan was for then-assistant press secretary Sean Walsh to escort us to the presidential suite atop the hotel as soon as the speech ended.

I turned away from Walsh’s direction for a nanosecond, the equivalent of taking my eye off the ball. When I looked back in his direction, there was no Walsh, no Texas colleagues, and hordes of realtors were headed my way as the ballroom began to empty. Panic was quickly setting in as I realized that I had no hope of tracking down the president’s location amid the throngs of people and vast net of presidential security throughout the hotel.

But George Herbert Walker Bush had my back. When it became clear upstairs that I had been misplaced, he instructed Walsh to quickly hunt me down and made sure that anything he said before I arrived would be recorded. “We’ve got to help the little fellow out. We’ll make sure he’s covered,” Walsh, who is now a principal in a law firm with former California Governor Pete Wilson, remembers the president saying. I wrote a front-page story from the roundtable interview with no hint of the near-disaster.

Other old-school Texas reporters have their own treasured anecdotes from their days covering Bush. Dave Ward, who was a legendary anchor for nearly fifty years at Houston’s KRTK Channel 13, met Bush when the future president was an alternate delegate at the 1964 Republican National Convention in San Francisco. Ward, who still does feature segments for the station, was covering the convention as a Houston radio reporter and was hunting for Texas delegates to comment on a group of protesting hippies trying to block the entrance to the convention hall. He got what he considered a gem from Bush, who said the delegates would be amenable to talking to the protesters “if they would go home and take a bath and put on some decent clothes.”

Two or three years ago, Ward remembers, he bumped into the former president at a Houston restaurant. “Hi, Dave,” the president said. “You had any trouble with hippies lately?” Ward said he remained in touch with the president throughout his career and was twice invited to the White House. After Ward won a Guinness world record for his 49 years and 218 days as an anchor, the Bushes sent him a letter of congratulations signed by “your biggest fan, George H.W. Bush.”

Tom DeFrank, who was born in Houston, grew up in Arlington, and graduated from Texas A&M, knew Bush for more than four decades in a Washington career that included Newsweek, the New York Daily News, and the National Journal, where he still covers the White House as a contributing editor. The two’s Texas ties helped fuel a long-running friendship, DeFrank remembers. At a White House Christmas party in 1989, DeFrank and his future wife Melanie were being greeted by the president when Bush noticed an engagement ring on Melanie’s finger. “He gets all excited and the receiving line just stops,” DeFrank said, recalling how the president pointed out the ring to First Lady Barbara Bush and talked about how DeFrank had just gotten engaged. Two weeks later, the couple was invited to a movie at the White House. “That’s the kind of guy he was,” DeFrank recalled. “He was very kind and very decent. He was, as we say in Texas, the real deal.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy

- George H.W. Bush