This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

“Does a swan go next to a blow-dryer?” Two mothers are peering anxiously over a showcase filled with dozens of gold and silver bracelet charms, each depicting in miniature a facet of summer-camp existence: saddles and trampolines, megaphones, golf bags, badminton birds, bows and arrows—even an unbelievably tiny electric fan with rotary blades, no bigger than a thumbnail. Don’t call them cute—Jim Avery hates anything smacking of cuteness, but they certainly are . . . well, charming. On this mid-August Hill Country afternoon, fathers sip beer in the shade of live oaks while their wives and daughters reenact an end-of-summer ritual: buying jewelry at James Avery Craftsman in Kerrville.

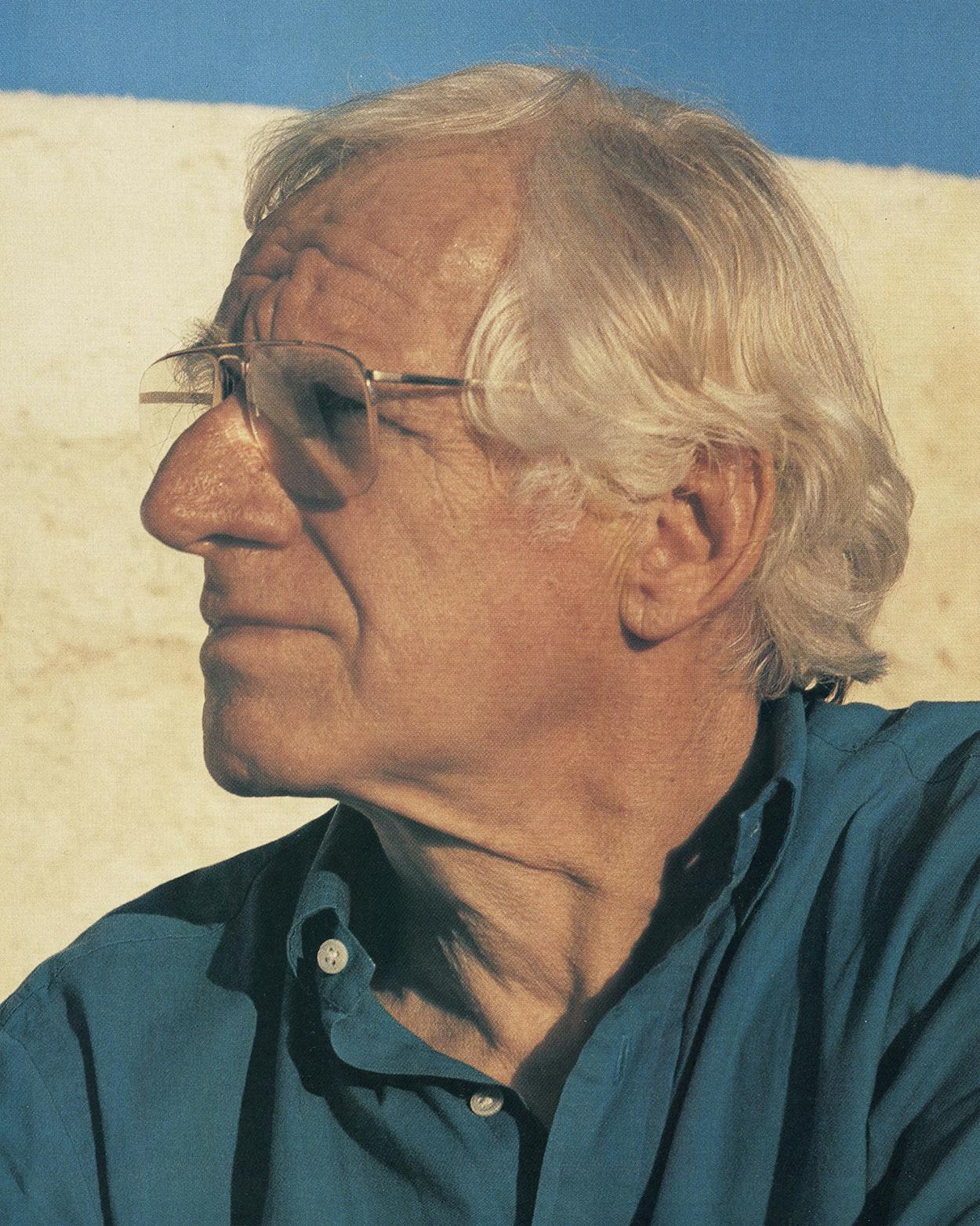

Lumbering up to the stone terrace is 68-year-old Jim Avery himself, tall, lean, and handsome. From among the shoppers a middle-aged woman rushes forward. “Oh, Mr. Avery, can I shake your hand?” Wearing a ponderous silver necklace, huge medallion earrings, and a profusion of rings and jangling bracelets, she is the antithesis of the James Avery look: extravagant, immodest, overdone. But as always, Jim is at his best in the company of a fawning female. He smiles disarmingly at the woman, even compliments her jewelry, and gamely poses for a snapshot.

For nearly 35 years, a visit to one of James Avery’s stores has been a privileged rite of passage in Texas—an adolescent girl’s introduction to real jewelry. It has been a kind of spiritual pilgrimage as well. Jim’s reawakening to Christianity in 1951 is part of the mystique of his creations; his spiritual beliefs frame the corporate ethic. Every pendant, pin, belt buckle, and bookmark is invested with ideology, a sense of virtue and integrity that are the intangible assets of Jim Avery and of James Avery Craftsman. To the thousands who have purchased the jewelry over the years, the man and the message are the same. Buy the jewelry, and you buy a piece of the legend.

But last year something went terribly wrong. Jim Avery was sued by one of his longtime employees, prompting a nasty trial that exposed the private world of the famous jewelrymaker. Day after day, the seamy indiscretions of his professional and personal life unfolded in the courtroom: stories of how Jim romanced his 32-year-old personnel manager and ditched his third wife, drank to excess, cursed at his employees, and broke promises. For a devout Christian, he was behaving in a most unchristian way. By the time the trial was over, the James Avery legend had been replaced with the image of a fragile, vulnerable sinner who had tried to do right but failed. His company was in as much disarray as his personal life, and his top executive had resigned under fire. Jim Avery had become Kerrville’s bad boy—“the man in the myth,” as one former employee calls him. “You know, the story that’s supposed to be true, except it isn’t.”

This is the old Schreiner home. They made it into a museum. But then,”—he gestures with a gargantuan hand toward a featureless brick facade—“they put up this crap.” Jim Avery and I are touring Kerrville in his sleek black Volvo. He is an intense and immensely attractive man, with shaggy white hair, a high forehead, a crimson face, and a huge toucan nose. Jim steadies a ceramic mug sloshing with coffee and grouses about why the town looks so bad. He has got a point: Kerrville’s architecture is a disjointed hodgepodge of modern buildings alongside older ones whose graceful effect is, more often than not, marred by gaudy signs or clunky air conditioning units. “Look at that stucco,” says Jim, pointing at Schreiner’s department store. “It’s great, but they tore down the old Bluebonnet Hotel. Now it’s a parking lot. Even the old courthouse was nice—look how they messed that up.”

To Jim, Kerrville’s impoverishment goes beyond brick and mortar. He thinks that there are too many mobile home parks and vacation houses filled with backward-looking, penny-pinching retired folks. They don’t like school taxes, he says. They don’t recycle. They’ve allowed developers to take over the town. “Look at this!” he bellows. We are speeding past a Wal-Mart engulfed by an enormous parking lot. “Love that landscaping.”

We pull up at Jim’s cabinet shop, on a side street, where the company’s workbenches and cabinets are handmade. Inside, Jim discovers an employee hard at work on a wooden form holder, an open-ended box designed to fit the company’s order forms. The employee, a middle-aged Hispanic man, holds up several of the boxes that he has just completed. “What’s going on here?” Jim thunders. “Jeez, we don’t need any more form holders. We need catalog holders. Who told you to make form holders?” Jim looks down at his feet, does a sort of back-and-forth shuffle, scratches his head, and looks severely wounded. But the employee looks even worse. “Hold off on these,” Jim barks. We get back in the Volvo and shoot off, leaving the dejected employee in the doorway.

Later we drive through a part of Kerrville known as the Settlement, a largely Hispanic area. “Now, this is my neighborhood,” Jim says with satisfaction. “These are my people. I know them, and they know me.” Indeed, the majority of the two hundred employees who work at his Kerrville headquarters are of Mexican origin, partly because they satisfy the company’s need for unskilled labor, and partly because Jim has genuinely made an effort to hire and promote them. “They’re warm,” he says. “They’re friendly. I admire them, their culture. They love to play music. They know how to enjoy life, celebrate. I like to help them.”

Back in his office, behind a polished wooden desk, Jim is restless and fidgety. He clasps and unclasps his hands and readjusts his limbs. He is fanatical about his physical condition, doing six hundred push-ups each morning in 33 minutes—32 when he feels good. He knows his precise weight at any given moment. It hovers between 176 and 178 pounds, although 172 is his ideal. Jim would like his employees to be as physically fit as he is. In fact, what he really wants is for those closest to him to adopt all the values he preaches, even if in some cases he doesn’t practice them himself. “He expects a greater degree of perfection from us and more reverence for his opinions,” says his son George. “I think he expects us to be more like him.”

James Avery grew up in a traditional midwestern Presbyterian family, the rebellious son of an insurance man and a seamstress. According to Jim, the watershed event in his life occurred when he was a 29-year-old art teacher at the University of Colorado. His wife of seven years, Mona Pierce, walked out on him, leaving him to care for their two toddler sons. Jim had married Mona in 1944. He was training to be a bomber pilot; she was vivacious and temperamental—and on the rebound after her boyfriend had been shot down in a mission over Europe. The marriage had been stormy, strained by drinking and violent fights. In the summer of 1951 Jim took the boys to visit his parents in Chicago. When he returned to Boulder, he found a note from his wife: “Call my lawyer.”

Mona’s departure, as Jim relates it, was the first thing he encountered in life that he had no control over. At his mother’s suggestion, Jim visited an Episcopal minister in Boulder and was drawn to the ritual and rich symbolism of the church. He came to believe that there was a greater force at work in the universe, a force embodied in Jesus Christ. Agnosticism, he decided, wasn’t working. “I was stepping on too many people,” he said in a 1979 interview. “I had made a big mess of my life.” Jim was playing with his sons on the floor of the Canterbury Club, an Episcopalian social center on campus, when in walked a young coed named Sally Ranger.

Sally was from an established Kerrville family; her grandfather had been a wildcatter in the Ranger oil field. A 19-year-old sophomore, she had shiny black hair, sparkling eyes, and a Merle Oberon freshness. Now remarried, she recalls the first time she saw Jim. There was “a look of abandonment” about the tall man with the tiny children, she says. “I guess it was love at first sight.” But there was a problem: Jim was still married. Sally dropped out of school and returned to Kerrville while he and Mona were divorced.

In June 1953 Jim and Sally had a storybook wedding. The ceremony took place under a broad oak tree in the back yard of the Ranger home in Kerrville, on a rise with an expanse of the Hill Country as a backdrop. Sally wore a prim white gown buttoned up to the neck—“That was Jim’s idea,” she says. “That was the way he wanted me to look.” They spent their honeymoon in a remote mountain cabin in Idaho. Jim had taken along some tools and passed the time making jewelry, including several crosses. One was for Sally, fashioned out of silver, ebony, and the gemstone from his Air Force ring.

Jim and Sally spent the next year in Minnesota while he pursued a master’s degree. But he flunked a required French course, and so, with no money, they headed back to Texas and moved in with Sally’s mother, Gladys Ranger. Jim was restless and at loose ends. Teaching wasn’t expressive enough for him, and he thought of taking up woodwork. To make a living, he considered driving a Schlitz beer route. When that fell through, his mother-in-law offered her two-car garage as a studio. In it, Jim built a workbench and started making jewelry. He sold his first pieces from that garage. Then, when Gladys began running the commissary at Camp Mystic, upstream on the Guadalupe River, she also sold some of Jim’s jewelry. The campers proved to be steady customers. At summer’s end they would return to their hometowns talking about the rural artisan who specialized in Christian symbolism: crosses, doves, fish, and lambs.

Jim worked in that garage for three years with Sally at his side, living an existence that was the apotheosis of a nineteenth-century craftsman—designing, sawing, and polishing each piece of jewelry himself, supporting his family by the labor of his hands. Later Jim would look back and see those as halcyon years. That period had a quality of innocence and tranquillity that he would attempt to recapture over and over.

Jim’s early jewelry was special, by far the best work that he has ever done. The principles he had adopted for his personal life were mirrored in his jewelry. He liked a balanced, uncluttered look—nothing gimmicky, nothing gaudy, no lines or decorative elements that didn’t serve a purpose. His designs were clean, almost childlike: a dove with circular swirls in its wings, a cross based on a Pueblo Indian pattern, a linear fish encircling a cross. Each piece felt as good as it looked, weighty and well made. “He had a strong, bold statement with a hammer,” says Jim Morris, one of the company’s early designers. “If he made hammer marks on his pieces, they weren’t arbitrary, they were purposeful.”

During the four years they lived in Gladys’ house, Jim and Sally had three sons. By 1957 the business had outgrown the garage, and they built an airy house and studio down the hill from Gladys. It was an idyllic place to live and raise children. Soon there would be a fourth son. Mona had taken custody of her two boys, but they visited Jim and Sally in the summer, when there would be six brothers racing around, exploring the countryside. There was a horse, a donkey, chickens, goats. Off of one end of the house was a baseball diamond. As far as Jim was concerned, it was as pure an existence as could be found. The house had no air conditioning, for instance. Jim said he had moved to the country for the fresh air and wasn’t about to shut his windows. There was no television, either. The reason, says Jim’s son Tim, was largely aesthetic. “He didn’t want an antenna on the roof to break up the landscape.”

Jim was a stern disciplinarian, and although proud of his sons, he could also be emotionally remote. More than a few people noticed how he treated his boys when they worked for him during summers. He would criticize them in front of employees, saying, “You’re dumb” or “You’re stupid” or “Why don’t you do anything right?” Sally was the sensitive one, a model mother and wife. She made everything from scratch: bread, coffee-cake, cookies, ice cream. Her dark hair hung down to her waist, and on warm days she would wash it on the patio. Jim transformed the image into an eighteen-karat-gold ring depicting a woman leaning over, hands uplifted, her long hair streaming down her face. (Sally still wears the ring every day.) Jim built a small sauna in the house, and after going for a run, he would sit inside it and knock on the wall for Sally to bring him a margarita, Sally recalls. “And when he knocked, I came.”

In 1967 Jim and Sally bought property on the opposite side of the baseball diamond, and there he built larger studios, workshops, and a headquarters for the growing business. What had started out as a jewelry concession at a summer camp had expanded through a network of church gift shops and clothing boutiques into a statewide business, tapping into what one consultant called the “furs and station wagon market.” Above all, James Avery Craftsman was a Christian company—not in the sense that every employee had to attend church or that prayers were said before meetings, but one in which Christianity was the backdrop. Christian symbols accounted for the majority of the jewelry line. Biblical quotations highlighted company memos. And Jim expected his employees to adhere to Christian tenets. Jim set himself up as the best example: He taught Sunday school and was a lay reader for Kerrville’s Episcopal church, where he and Sally introduced the first black members. He was also extraordinarily generous, lending money to friends, giving bonuses to employees, donating to good causes.

By 1971 James Avery Craftsman had 35 employees and $400,000 in annual sales. Yet the business suffered from a lack of planning. The problem was that, at heart, Jim was a designer. “He had a vision of the values of the company, but he didn’t have the ability to make it happen,” says one former manager. What Jim needed was someone with business sense, someone who could help him carry out his vision, someone who could tolerate his idiosyncrasies. Someone like Chuck Wolfmueller.

Chuck came from an old Kerrville family. He was working on a master’s degree in business at the University of Texas at Austin in 1971 when he was assigned to do a company analysis as a term project. Chuck chose James Avery Craftsman: His paper on improving production earned him an A in the class and found its way to Jim Avery’s desk. Jim hired him as production manager when Chuck was only 23.

When Chuck started work in May 1971, the company was still filling orders from the previous Christmas. Much of Jim’s equipment was antiquated. Chuck updated it and brought in-house various parts of the manufacturing process that had been done elsewhere. He set up a machine shop to make tools and dies. He opened a chain factory. He persuaded Jim to launch a string of retail stores. So successful were Chuck’s ventures that within the company, he became known as a boy genius. It was said that Chuck could get Jim to do anything. “Chuck knew exactly how to manipulate Jim,” says Bobbie Covey, who managed the Kerrville retail store. “All he had to do was plant a seed,” she said, and Jim would think the idea was his own. And Jim took Chuck under his wing with uncharacteristic tenderness. “The first thing Chuck did was wreck a truck,” says Sally. “And Jim said, ‘Well, that’s all right.’ Now he would have killed his sons if they did that.” Soon Jim and Chuck were running the business side by side. In Chuck’s first year, sales increased 40 percent, as they did for each of the next six years. By 1974, Chuck was on the board.

As a boss, Jim was demanding and often difficult. People who have worked with him speak of his enormous energy, his enthusiasm, his impatience, his perfectionism. He set high standards, but they could change overnight. He seemed guided by whatever passion possessed him at the moment, which made for constant chaos. Former sales manager Pat Thalken recalls the time Jim suddenly seized upon a ring that had been in the line for years, a solid seller. “The shoulders, the shoulders are too high,” she remembers Jim wailing. He took out his pencil and started scribbling, then sent the ring back to the designer to rework the mold. Another time he ordered all of the molds for the animal pins reversed so that the creatures wouldn’t appear to be walking off the wearers’ chest.

Every piece of jewelry that came off the line had to reflect what Jim called “an honest use of materials.” He approached everything with the same aesthetic: a stucco wall in one of his stores had to have a real brick wall underneath the stucco, not an artificial one. In Jim’s ideal world there would be no fakery, nothing that disguised itself as something else—no margarine, for instance, no powdered cream substitute, no wood-grained Formica, nothing that wasn’t completely pure and natural. Once, in the spring of 1989, Jim had every plastic item in the main employees’ lunchroom thrown away—cups, glasses, anything that wasn’t pottery or ceramic.

Despite the unusual demands, Chuck Wolfmueller kept enough order for the company to benefit from Jim’s indisputable talent. The first retail store that Chuck encouraged Jim to open was in North Dallas, near Valley View Mall. The decor set the tone for all the stores that followed: white stucco walls, oriental carpets, antique wardrobes and trunks, wall sconces—the kind of rustic elegance you might find in someone’s living room. The Dallas store wasn’t an immediate success. Neither was the second, in Southern California, nor the third, in Laredo. But the idea took off with the fourth store, in Houston near the Galleria. Customers packed the showroom. “We’d take the surplus jewelry down there and dump it on the floor in the back room,” says Chuck, who now lives in Albuquerque, “and they’d put the pieces on the counter and customers would take them right off the trays.” That store alone did $400,000 in sales for 1975. And the next, in San Antonio’s Stanley Square, did even better. The company didn’t open another retail store for two years to allow manufacturing to catch up. But the foundation had been laid for the James Avery empire.

Even as the legend of James Avery grew, his private life began to diverge from his public image. The catalyst was Carmen Espinoza. She came to the company in 1971 as a wax shooter on the assembly line, earning minimum wage in what was the lowest-ranking job at James Avery Craftsman. But Jim took a liking to her and moved her off the line and into the showroom. Carmen was the dissatisfied wife of a produce manager in a local grocery store and the mother of three children. Raised in Mexico, she was petite and pretty, and she unabashedly adored Jim. He was approaching fifty and once again restless.

In her new position, Carmen began to spend a lot of time in the boss’s office. “Carmen was using Jim to discuss her marital problems,” says Bobbie Covey. “He was quite flattered. She came in one day and said she loved him.” Jim had never been a womanizer, but he was extremely susceptible to female attention. The affair between Carmen and Jim went on for six months before Sally found out. But on some level, she must have known. At Jim’s insistence, Carmen and her husband had begun socializing with him and Sally. One night after the two couples had gone to dinner, Sally came home and burned the dress she had been wearing.

In October 1971, when Sally was in the hospital recuperating from a hysterectomy, she confronted Jim with her suspicions, and he admitted that he was in love with Carmen. Sally told Jim, “I can get over this. Don’t throw away your marriage and your four sons.” But Jim had made up his mind. He moved out of the house and a year later asked for a divorce. As he told Sally’s sister Marilyn Fierst, “God made me creative. I can’t be creative with Sally anymore. She’s so dull, boring, and uninteresting. God has given me new inspiration—in the form of Carmen.”

When Jim walked out on Sally, as one resident put it, “All of Kerrville was in an uproar.” Sally and her family were beloved in the community. While Jim had always been thought of as somewhat eccentric, for the first time, Kerrville residents began to wonder about his character. Years later, Jim acknowledged in an interview that the problem in his marriages was himself. “I’m too intense, too outspoken, too thoughtless, too tactless, and too inconsiderate. I guess you could say I’m, ah, hard to live with.”

Marrying Carmen was a way for Jim to rejuvenate himself, “get back to the basics,” as he said at the time. He and Carmen moved to Laredo, where he set up a small factory and a retail store. Jim worked in the studio while Carmen sold the jewelry. He bought a single-engine airplane and flew to Kerrville several times a week to keep an eye on the company. But for the most part, he tried to live a simpler life, a throwback to the golden garage days. In his absence the business was run by Chuck, Gladys, and Sally—who had kept the house and half of the company’s stock. But the Laredo venture was ultimately a financial flop, and in 1976, after Sally had remarried and moved to Cuero, Jim folded the operation and returned to Kerrville with Carmen.

All this turmoil took a profound toll on the Avery boys. Jim and Sally’s third son, Stephen, the one who “had the most friends, was the most fun-loving, the most outgoing,” according to one of his brothers, began to have emotional problems. A year after the divorce, he slit his wrists in a failed suicide attempt. Sally and Jim tried to help. They got him a psychiatrist, even sent him to a state mental hospital for a while. When Stephen was nineteen years old, his father bought him a brand-new Ford Fiesta. Two weeks later, Stephen drove it off a bluff outside of Kerrville, stepping out just in time to save himself. On Father’s Day in 1978, Stephen entered his brother Chris’s empty apartment in San Antonio, placed a hunting rifle under his chin, and pulled the trigger.

Considering the astronomical growth of James Avery Craftsman in the seventies and eighties, it’s not hard to understand why Chuck Wolfmueller came to see himself as the company’s savior. Chuck made the day-to-day decisions, freeing his boss to concentrate on long-range plans. Jim was no longer designing every piece of jewelry but would sketch out his ideas and hand them over to his staff to finish. Gradually, the designs broadened beyond Christian symbolism to a more generic line, one that had a wider, more commercial appeal. Now there were rings with eagles on them, earrings shaped like kites, tie tacks that looked like bagpipes. Though solid and well made, they were not as bold as the early pieces: “Mediocre,” says one former employee.

But the business was flourishing. When Sally sold her half-interest back to the business in 1979, she discovered that her $250,000 share had grown in value to $3 million. In 1980 the company launched an aggressive mail-order catalog business. Catalogs lured traffic into the retail stores, and retail sales offset catalog costs. The company’s exclusive image was bolstered by a policy of never offering discounts or special sales. James Avery Craftsman stood for enduring quality. At Christmas, Mother’s Day, or graduation, the gift of a James Avery piece of jewelry became a tradition—especially among adolescent girls. From 1975 to 1985, the company’s sales went from $1.5 million to $14.3 million, with eighteen new retail stores. In 1986 Chuck became president.

By then, Jim was 64 years old and feeling his age. He was still a fitness maniac and extremely healthy, but he told friends that he was worried about whether the company could continue without him. In 1984 Jim had put the company up for sale. But he had drawn only one bid, for $5 million. That was far too low by Jim’s estimate, so he withdrew the offer and, on the advice of a consultant, asked Chuck to come up with a plan for a team of James Avery corporation managers to purchase the business. The plan would satisfy two key goals: allow Jim to gradually pull away, while ensuring that the company would endure with its leadership and values intact. In December 1985 Jim presented to his seven top managers a buyout plan that established sales and profit goals from 1986 to 1991. If the goals were met, Jim would award the managers bonuses that they would then use to purchase stock. In six years the company would buy back most of Jim’s stock, providing him with the capital he needed to retire and leaving 80 percent of the company in the hands of the managers.

For the seven managers, it was a breathtaking opportunity. By 1991 the company could be worth $30 to $35 million, giving each manager stock worth at least $2 million—more than $5 million in Chuck’s case, since he had more stock. But there was considerable risk: Each manager would have to assume a personal debt of $50,000 to make the initial stock purchase. It was a gamble they were eager to take. On May 13, 1986, all seven managers signed the agreement by which Jim sold them the first 48,000 shares.

In 1986, the first fiscal year, the company fell slightly short of its goals. But by the following year, after-tax profits were $850,000, exceeding the target by $50,000. In 1988, with a goal of $900,000, James Avery Craftsman earned $1.32 million. And in 1989 the company netted more than $2 million. But by that time, Jim Avery was deep in another marital crisis, once more played out in public.

It began with Sylvia Flores. Sylvia had started at the company as a part-time typist when she was still in high school. With a James Avery Foundation scholarship, she attended Pan American University in Edinburg. In 1976 she dropped out, married her high school beau, and went to work full-time for the company. From the beginning Sylvia was, as one of her colleagues put it, “a company woman.” She was tough and determined, and she set out on a course of self-improvement. Sylvia made no secret of her admiration for the boss, and he encouraged and promoted her. In 1978, Jim asked her to put together the company’s first personnel department. He sent her to business workshops, where she sharpened her managerial skills and polished her image. She kept a library of self-help audiotapes. She lost weight. And in easygoing Kerrville, she began dressing for work in high heels and severe black suits. She was known as an efficient, if somewhat abrasive, manager—one who was not especially liked by other employees. Sylvia and her husband, Ismael, became friends of the Averys’; Jim helped Ismael get a loan to open a beauty salon next to the Mexican import shop Jim had set up for Carmen; Sylvia became one of Carmen’s most intimate friends. In the summer of 1987 many employees noted that Sylvia’s relationship with the boss had grown quite cozy. She was 32 at the time—only half Jim’s age and eleven years younger than Carmen. Jim began spending long periods of time in Sylvia’s office, sometimes all day and into the evening hours. He would bring flowers to her desk. Says one employee, “Everybody out there knew something was going on between him and Sylvia.” In December 1988 Sylvia collected money from the employees and bought Jim a $600 Baccarat vase for Christmas. A few days after he opened it, the vase appeared on Sylvia’s desk, with fresh flowers. The other employees were infuriated.

Sylvia Flores’ ascent within the company coincided with the downfall of Chuck Wolfmueller. It was as though the more she came to fit Jim’s idea of perfection, the more flaws he perceived in Chuck. In Jim’s eyes Chuck was hesitant, inexpressive, and somewhat overweight. Jim began to think he had made a mistake in promoting him. Sylvia, on the other hand, was supplying the boss with exactly what he craved: obedience and flattery. Her ideas echoed his. She openly called him her mentor. “I think Jim was in search of the perfect heir apparent, and Sylvia played that role well,” said one former manager. “She idolized him—absolutely idolized him.” In February 1988 Jim sent Sylvia to a five-day leadership workshop in San Antonio where participants were encouraged to define their goals. According to Carmen’s deposition, when Sylvia returned, she announced to Jim that she loved him.

Like Sally, Carmen had suspicions. Several times she had asked her friend Sylvia if she knew what was wrong with Jim. Sylvia had cagily replied that Carmen would have to ask Jim herself. The showdown came on June 22, 1988, when Carmen confronted Jim, and he admitted that he loved Sylvia. The next day, Carmen stormed into the office and challenged Sylvia: “So you are the one. You, my friend, the one that I trust.” Sylvia could only reply, “Well, people change.”

By now, rumors were thick throughout the company. Chuck advised Jim that he had better do something. So Jim called an employee meeting and made an announcement. Characteristically, he said he wanted to be honest and clear the air. He and Carmen were having problems, he said. He and Sylvia had a deep respect and love for each other, but the relationship was “on a very high plane.” The following month, Jim and Carmen separated. So did Sylvia and Ismael.

Privately, Jim began to tell some of the managers that he was thinking of postponing the buyout. The reason, he said, was Carmen—divorcing her was going to be expensive. To one, he confided that he regretted leaving Sally; he had been unhappy for years. Not surprisingly, the news did not sit well with the managers, who had been counting on becoming millionaires by 1991. “If a guy can’t keep a commitment to his marriage,” said one, “how could he keep a commitment to us?”

By late summer of 1989, events were cascading out of control. Jim and Carmen had been haggling over a divorce settlement for a year. Morale at work had plummeted. Chuck was pacing the halls and barely speaking to Jim. On September 7, Jim called Chuck into his office for a talk. Chuck was not acting like a leader, Jim told him. He sensed that the company was adrift. The next day he followed up with a letter, heavily laced with Biblical quotations, in which he told Chuck to take charge, be decisive, lose weight, look “less stodgy and more trim”—as if he were “ready for action.”

Four days later, Chuck took the step that sealed his fate at James Avery Craftsman. He shot back at his boss with an acerbic eight-page memo under the heading, “A directive to walk your talk.” In it, Chuck told Jim that his moral life was in disarray, that he looked “a little shabby on the inside.” Mentioning Jim’s three failed marriages and his estranged children, Chuck suggested that Jim had never kept a promise in his life. He quoted extensively from the company’s employee handbook—drafted by Sylvia—in particular, the section indicating that any employee who places himself in “an extremely embarrassing situation” by not adhering to the company’s moral standards could face disciplinary action, even dismissal. In short, Chuck accused Jim of living a lie. “You can be the most warm, caring person that people love to be around,” he wrote, “or when you get egocentric you can be the most hateful jerk people have ever seen.” Chuck ended with a plea for Jim to bring Jesus Christ back into his life. The following day, Jim asked Chuck to resign.

In November 1989 Chuck filed a $12.3 million lawsuit against Jim Avery, Sylvia Flores, and the company. Jim responded with a counterclaim. Carmen, meanwhile, was still maneuvering for an ample divorce settlement. Jim says he offered to settle with her for $2 million. But as she told her friends, she was determined to get more than Sally had. She sued the company to prevent it from paying off Chuck before her. Then the management team began to fall apart. The treasurer was fired. In December Jim asked the remaining five managers to sign a statement releasing him and the company from all contractual obligations, including the buyout plan. The marketing manager resigned; the remaining four managers, who did sign the release, each received $10,000. Then, suddenly, with the divorce papers drawn up, Jim and Carmen announced that they had overcome their differences and were once more living together as husband and wife.

The James Avery trial lasted the entire month of March 1990, providing the town with an abundance of gossip and drama. Chuck’s position was that Jim’s relationship with Sylvia had contradicted the values of the company and led Jim to make poor business decisions—namely, backing out of the buyout agreement. Chuck also claimed that his privacy had been invaded when Jim broke into his desk with a screwdriver and had the contents photocopied. Jim’s defense was that he had never formally agreed to the plan. He accused Chuck of dredging up smut to make him look bad. Each day the courtroom was packed with an assortment of friends, enemies, relatives, employees. Chuck’s family was there; so were Sally’s and Carmen’s. Every morning Carmen walked in and, playing the role of dutiful wife, took her seat in the front row.

The trial had more than enough titillating details to keep the audience entertained. Jim admitted that he was in love with Sylvia but denied that the relationship had been physical. He said that he intended to live up to his commitment to Carmen; he “wanted to make it work.” Sylvia testified that she loved Jim “as one of the most wonderful, most giving, more caring individuals I have ever known.” But, she insisted, she wasn’t in love with him. Under questioning, they both admitted to spending part of a weekend together in November 1989 at the Doubletree Hotel in Dallas but insisted that they slept in separate rooms.

Other compromising details emerged in Chuck’s petition, such as the April 1989 workshop for store managers at the Guadalupe River Ranch near Boerne when Jim, somewhat drunk, leapt into a hot tub with his clothes on. The next morning, obviously hung over, his lip bruised, and his glasses broken, he stood before his employees and apologized for his behavior. Then he delivered yet another of his inspirational talks, punctuated with references to the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Sylvia was at his side.

In his deposition, Jim also acknowledged plowing his tan Mercedes into a bridge abutment in the fall of 1989. Charged with driving while intoxicated, he spent the night in jail. On the stand, Sylvia was forced to admit that she had lied about her education in her deposition. No, she hadn’t actually gotten her bachelor’s degree from UT-San Antonio. In fact, she admitted, she didn’t have a college degree at all.

For the jury, the question was whether the buyout plan had been legally binding. Ample evidence showed that, yes, Jim had agreed to the plan, but beyond the sale of the initial portion of stock, it amounted to no more than a verbal promise. It was a gentleman’s agreement, based on mutual trust. And while trust was the foundation upon which Jim had built his company—indeed it was a critical element in the slogans he had been reciting for years—it carried little weight in a court of law. The jury took just six hours to reach a verdict: Chuck was awarded $15,000 for the buyout plan and $350,000 for the invasion of his privacy, a judgment that was later reduced to $29,000. Chuck vowed to appeal.

Within a week of the verdict, Jim and Carmen were divorced. Carmen told the Kerrville Daily Times that she felt she had been used. Her only regret, she said, was that she had not gone through with the divorce the previous December. “I wouldn’t have put myself through all of this. I was naive. I believed in him.” But to many, it looked as though the reconciliation had been a setup, designed to soften the jury. In any event, Carmen got what she wanted—a divorce settlement worth $5 million, including $1.5 million in cash, plus $1.8 million to be paid over the next five years, five pieces of property (her house, her son’s house, her daughter’s condo, the import store, and a parcel of land in the country), three cars, a membership to San Antonio’s Argyle Club, and $25,000 credit toward the purchase of James Avery jewelry.

Five months later, sitting in her spacious home at the River Hills Country Club, Carmen looks serene. Like Sally, she continues to wear James Avery jewelry. And, like Sally, she says she bears no malice toward Jim. After her divorce, Sally bought herself a house at the seashore. These days, Carmen is busy designing her own house, to be built on property near Mountain Home. It will be a big house, Spanish-style, she says, with a small chapel. After she finishes the house, Carmen wants to travel. Time and money have soothed her ruffled feelings. “I suffered, and now I forgive him,” she says. “He’s so naive. He’s so open and vulnerable. You have to forgive.”

“If it’s right. Only if it’s right. It has to be right.” Once again, James Avery is in agony. At the moment, it’s about whether he should open a store in Washington, D.C. “If there’s one thing I’ve learned,” he says, his face reddening, “it’s that what I think and what I feel have got to be the same. They’ve got to meet.” Jim has a way of making a simple business decision sound like a moral crossroads.

In September, Jim and Chuck quietly settled the lawsuit. Neither side will reveal how much Jim paid to buy out Chuck. Chuck says that he is satisfied, but it’s clear that he is still seething about the way he departed from the company he had worked at for eighteen years. For his part, Jim is ready to put the past behind him. Sylvia, who declined to be interviewed, is getting her business degree at UT-San Antonio. Employees speculate that Jim intends to bring her back as president; Jim says only that he wants to make her an officer. Ever the exercise fanatic, Jim fell off his racing bike in late summer, broke his femur, and wound up in the hospital. Now he walks with a cane but still manages to get in six hundred push-ups every morning. Instead of 33 minutes, it now takes him 45.

In recent months Jim has tried to make amends. He still rehashes Stephen’s death, worries about Sally, regrets the hurt he caused Carmen. After years of emotional distance, his youngest son, Paul, has recently moved to Kerrville to join the business, and Jim talks about one day bringing him into management. Last summer Jim also invited his son Tim, who runs a cleaning service in Waxahachie, to make a similar move, but then changed his mind and called it off. There are reasons why Jim and Tim haven’t always gotten along. For one thing, Jim is critical of the way that his son’s wife, Jacque, looks.

Sitting in Jim’s office one day, I inquire about his tenuous relationship with Tim and Jacque. Does a person’s appearance really matter? More importantly, does Tim love Jacque? Are they happy?

Jim stammers a bit, shifts in his seat, scratches his head. “Well,” he says at last, “Tim is trim. Tim is conscious of the way things seem and look. Any man should be proud to introduce his wife to other people. I have a hard time introducing her—you know, ‘This is my son and my daughter-in-law.’ I mean come on.” Then he mentioned the other matter. Tim and Jacque are devout Jehovah’s Witnesses, a religion that Jim cannot fathom. To him, it’s a cult—one whose members do not even believe in religious symbols. “They go to the Kingdom Hall and do something over there all day long,” he says finally. “I don’t think they have any fun.”

Last year, in an attempt at reconciliation, Jim gave each of his five sons four thousand shares of stock, worth about $120,000 apiece. Needing cash, Tim and Jacque wanted to sell part of their stock right away. But this was not what Jim had in mind. He thinks they ought to keep the stock, he tells me, because it will appreciate. If Tim needs the money now, Jim would rather lend it to him. In fact, he has lent it to him, Jim says. He pulls out his checkbook and points to the stub from a $30,000 draft that he recently sent his son.

Not long ago, Jim tried to buy the old two-car garage, the one in which he started the business 35 years ago. He had thought of moving it down to his headquarters, as a kind of a memento. But after Gladys Ranger’s death last spring, the house became the property of Sally’s sister Marilyn. Bitter and angry at Jim, Marilyn said she would part with it—if Jim would cough up half a million dollars.

Perhaps Jim would have been better off if he had stayed in that rickety little garage, doing what he has always done best—designing. He loves to design so much that he would redesign Kerrville, redesign his life, redesign his children’s lives, even human nature, if he could.

Jim admits that he has made a mess of his life. But after all, he says, he’s only human. “I guess after all this stress I’ve been under, I still have this feeling, I mean, hey, lookit, if somebody says, ‘I’m a good Christian,’ I say, ‘Hey, I’ve never met one yet.’ So we all fall short. We’re all failures as far as God is concerned.”

Jim is so relentlessly open that it is tempting to sympathize with him. Yet there is something disturbing about his kind of remorse. “He can say, ‘mea culpa,’ yes, ‘it’s all my fault,’ ” says former employee Bobbie Covey. “He can beat his breast, but it’s kind of like going to confession. You’re absolved, and then you can go out and do it all over again.”

For now, Jim is satisfied to be back in control, running the company day by day. Nothing gets done right without him, he says. He’s outraged that a dealers’ catalog went out without a copyright mark and had to be recalled. He is irritated that his employees make so many careless mistakes. “I said something about this years ago,” he tells me.

Something about what? I ask.

“Details,” he says, impatiently. “You gotta take care of details. So I walk down here and I open the door and the door hits the wall. The doorstop is in the wrong place! I said, ‘Call maintenance so the door’ll hit the doorstop before it hits the wall.’ Jeez, why do I always have to be the one to take care of these things?”

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Kerrville