In early January, an employee armed with a video camera swept through the Austin headquarters of the Texas Department of Agriculture, making a record of every office: desks, bookshelves, computers, trash cans. Newly elected commissioner Rick Perry had ordered a top-to-bottom inventory, and his staff wanted to account for every item in the agency. Employees were asked to strip the posters, signs, and comic strips from their doors and hallways. Within days every vestige of the folksy, college dormitory atmosphere cultivated under former commissioner Jim Hightower had vanished. Gone was the rusty old plow from the lobby. Gone were the nostalgic Depression-era photographs from the walls. Gone were the agency’s subscriptions to leftist periodicals such as Mother Jones, the Progressive, and the Utne Reader. Unhappy with the transformation, old-time TDA employees began fleeing the department, their discontent exacerbated by the irony of Hightower’s unexpected defeat: While liberal governor Ann Richards holds court at the statehouse, Hightower is out on the street.

After six months as commissioner, Rick Perry has rearranged the agency’s furniture, both physically and philosophically, delivering the unmistakable message that, above all, he is not Jim Hightower. The two men could not be more dissimilar. A left-leaning Democrat, Hightower introduced policies over the past eight years that benefited consumers, small farmers, and the rural poor. He created farmers’ markets and boosted nontraditional products such as blueberries, exotic game, and Christmas trees. Under Hightower, the TDA was a quirky place, its zealous employees bonded by a sense of mission.

Perry is a conservative Democrat-turned-Republican, a former state representative from Haskell who is at home with mainstream agriculture: cattle, cotton, wheat, and produce. While Hightower’s maverick ideas placed him at odds with the federal administration—he relished taking jabs at President Bush’s farm policies—Perry recruited his deputy commissioner, Barry McBee, straight from the White House. And while Hightower was aloof and brooding, Perry is fresh-faced and chipper, just as you would expect a former Texas A&M yell leader to be. “He marches up to the lowliest employee, greets them by name, shakes their hand, and looks them in the eye,” says one staffer. “He’s as friendly as a puppy.”

But Perry’s affability has not assuaged fears that he has created an Orwellian bureaucracy. All workers are now required to wear name badges. “They’re fairly depersonalizing,” says one. “It’s humiliating to be tagged, as if we were cattle,” says another. Perry, who during the campaign hammered away at Hightower’s alleged breaches of ethics, has also distributed manuals on ethics. Despite the general emphasis on ethics in state agencies currently, some TDA employees felt Perry’s action implied they were cheating. Worst of all, they gripe, is the new Office of Internal Affairs, staffed by three former law enforcement officers, whose job it is to investigate ethical transgressions. Employees have been encouraged to report all suspected acts of malfeasance—in other words, to snitch on their fellow workers. “The implication is that they are policemen and they are there to watch us,” says former Hightower speech writer Betsy Blair, who quit the agency in March.

In another small but telling change, Perry has junked the official TDA stationery, printed on tan recycled paper, and replaced it with white stock bearing a departmental seal and his name at the top. “It says that now we’re a little more pukka,” comments one director. All outgoing mail, which must now be checked by the public information office, has been standardized: “Please set the margins 1.25 inches from either side and 1 inch from the top and bottom. The date should be centered and six spaces down from the top of the page,” a memo instructed.

These changes are not meant to be intimidating or insulting, Perry insists. He says he instituted name tags—he wears his own on his belt—because he likes to call people by their first names. I was very sensitive to the fact that I’m different from my predecessor. There was an expectation that I was going to come in here and pour people out,” he says. “It was three months into the administration before anybody got fired.” He also observes that all political transitions are traumatic. When Hightower took over from conservative Reagan Brown in 1983, he created a furor with his populist rhetoric and the way he filled the top ranks with out-of-staters—including his live-in girlfriend, whom he installed as a non-paid assistant commissioner.

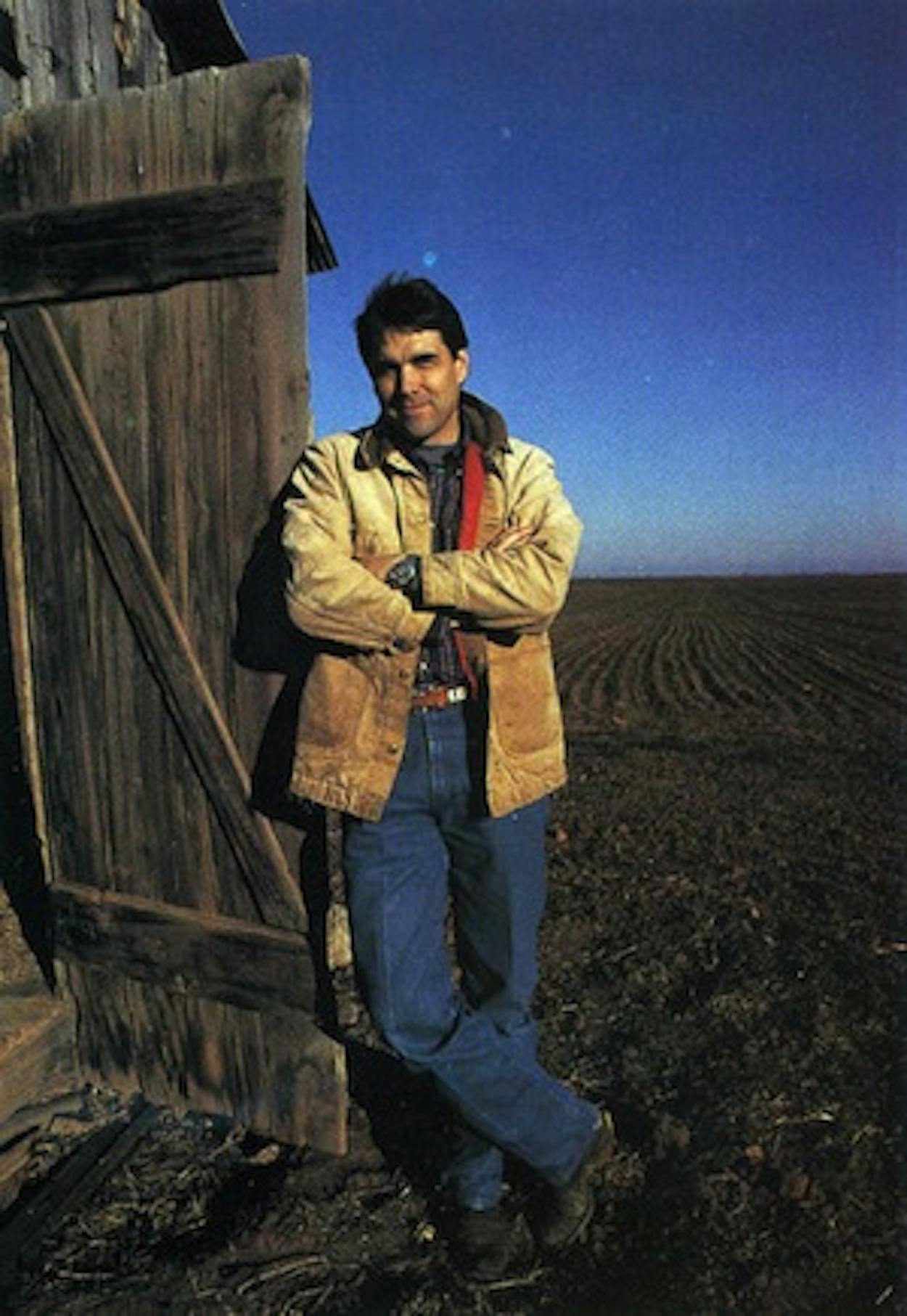

Perry isn’t the type to defy convention. With his orderly desk adorned with family photos, his crisp, fitted white shirts, and his wholesome features, Perry personifies decorum. A writer for Top Producer magazine said Perry had a “Kevin Costner smile,” but that is too glamorous. Rick Perry is, by nature and upbringing, a regular farm guy who promises to stand up for the rights of every other regular farmer and rancher in the state.

At least that’s the idea he campaigned on. Six months in his tenure, some observers are getting antsy. Just what does Perry intend to do? Unfortunately, no one knows. Perry promised to unveil his policies in June, at the end of an intensive “strategic planning process.” Management specialists have been conducting three-hour planning conferences—”sort of open brainstorming sessions, where we’re asking employees what are the strengths and weaknesses of the department,” McBee says. One staffer who recently participated says she was shown a film about how human beings get stuck in behavioral patterns. “They used the word ‘paradigm’ a lot,” she said.

So far, more than 75 employees have left the Austin office, having either quit or been laid off. Others are brushing up their résumés and feeling besieged. “Our adversaries have come in and taken over,” says one. “We are the vanquished.” Some are angry at their former boss for conducting a lethargic campaign and losing the election. For these Hightower loyalists, it is hard to abide being ousted just as a liberal has made it to the governor’s seat. “We all thought we were going to be part of a new epoch,” says one, “but instead we got left out.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Rick Perry