The best horror-movie directors hold that the ideal way to create terror is to never show the audience the boogeyman, or to do so only sparingly. Our current political reality, in the telling of the tea party group the True Texas Project, is nothing less than a horror story: the border is overrun, elections aren’t secure, and some abortions are still allowed. So it was fitting that the tale’s boogeyman, Greg Abbott, was absent from the GOP Gubernatorial Round Table the grassroots group held Monday night at Grace Woodlands church, in the north Houston suburbs.

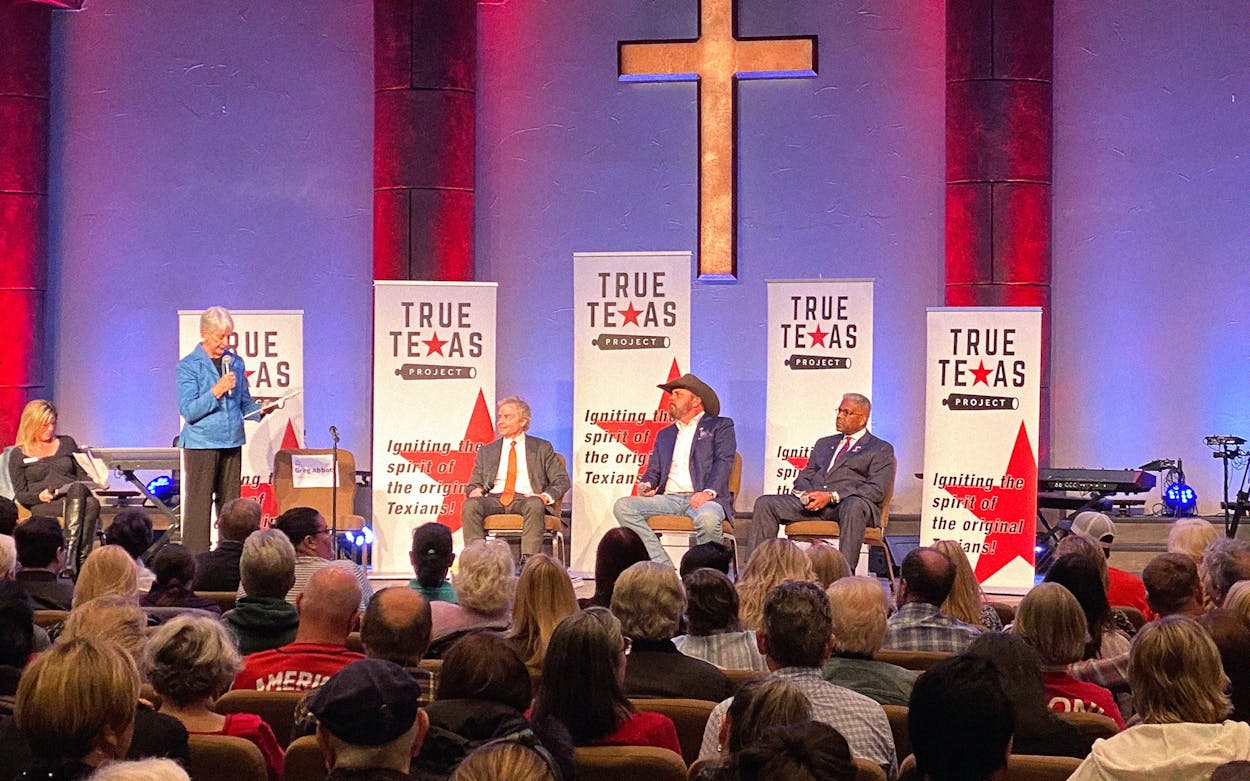

The stage, beneath a gold cross, was set for four: Don Huffines, the former North Dallas state senator who launched his candidacy in opposition to COVID shutdowns; Chad Prather, a right-wing YouTube star and comedian; Allen West, the erstwhile chair of the state GOP; and an empty chair for the governor bearing a sign with his name. (Julie McCarty, the CEO of the True Texas Project, told the audience Abbott had been invited; the governor’s spokesman, Mark Miner, did not respond to Texas Monthly‘s calls by press time to confirm that.) When McCarty succinctly summarized the group’s stance—“we are firmly anyone but Abbott”—she was met with applause from the crowd of some six hundred right-wing grassroots activists.

There was only one thorny issue, it might seem. In the months since Huffines, Prather, and West announced they were running, Abbott had signed laws allowing Texans to carry handguns without permits, restricting abortion more than any other state, and making voting more difficult in the name of “election integrity.” So where, exactly, had he fallen short? The candidates, as well as the event organizers, had plenty of answers. For ninety minutes, Abbott’s challengers hammered Abbott for what they see as his shortcomings: not totally banning abortion; not ending gender-affirming care for minors; not cracking down on district attorneys who don’t pursue certain low-level drug charges; not putting a stop to “immoral” and godless property taxes; not combating the federal government (in unspecified, but surely holistic, ways); and not completely locking down the border while ignoring international asylum law.

Huffines, Prather, and West never directed negative attention at one another and instead kept their sights trained on the governor, though they had the keen political sense to not directly address the empty chair. Huffines, the policy technician of the group, warned of the impending end of Texas due to an “invasion” of immigrants and Californian Communists with their blue-state values. “Any way you define it, it’s an invasion,” Huffines said, promising that he’d attempt to economically sanction Mexico by shutting down international bridges into the country until the cartels were eradicated. “I love Mexico, but right now they’re being a really bad neighbor.” Huffines struck an Andrew Jacksonian tone in explaining how he’d fight against threats international and domestic—by avoiding coordinating with federal immigration authorities, deporting migrants on capture, and bringing prayers back to schools and daring the Supreme Court to come to Texas to enforce the separation of church and state. “This is Texas; we’re not going to ask permission for anything.”

Prather, whose quick wit repeatedly drew laughter, agreed with Huffines’s characterization of threats to the state and called for putting Texas secession on the ballot to send a message to the rest of the country. He compared Abbott negatively to several historical counterparts. “The founding fathers would roll over if they knew people were having to rent their property for the rest of their lives,” Prather said. “If Israelites six thousand years ago could figure out how to navigate around property taxes, then surely the most conservative fiscal minds in the state of Texas in the twenty-first century should be able to figure out a plan as well.” Speaking about the border, Prather said he knew “half a dozen Special Forces retirees right here in Montgomery County that will fix the border issue in six days.”

West criticized Abbott’s border crackdown, Operation Lone Star, calling it a feckless “political optic” and promising to tax remittances migrant workers send back to Mexico or Central America. “The state of Oklahoma does it at one percent,” he said. “I think Texas is ten times better than Oklahoma; we’re going to do it at ten percent.” As for outsiders bringing left-wing values to Texas, the former member of Congress from Florida warned the “corporate fascist oligarchs” that Texas’s culture would not change if he were governor. He dared companies who opposed his opposition to trans rights to boycott the state if they had a problem with it. “You think they’re going to take the Cotton Bowl and put it anywhere else?” West asked.

So closely did Prather, Huffines, and West’s policy prescriptions and rhetoric match that they more or less formed a panorama of the evolution of right-wing man: podcaster, politician, and provocateur. Near the end of the debate, the format switched to a lightning round: each candidate was given a double-sided thumbs-up/thumbs-down poster and asked to signal his stance on twelve policy positions, ranging from whether legislators who break quorum should be impeached (yes) to whether there should be a third gender option on the Texas ID (no). “These questions are too easy,” Fran Rhodes, president of the True Texas Project, remarked halfway through. McCarty acknowledged the unanimity of the responses, but said it was important to get the candidates on record lest they ever walk back their promises.

It wasn’t until a question on abortion, which McCarty said remains “a top concern among most true Texans,” that the candidates demonstrated any notable disagreements—and even then only on a personal level. Huffines and Prather, who said that while he grew up in Georgia he calls himself Texan because he was conceived in Dallas—“that’s how pro-life I am”—both opposed all abortions. West demurred, after telling the audience he had helped Lubbock pass an ordinance last year to become a “sanctuary city for the unborn.” However, West said, if his daughters were “criminally violated,” he’d “love to be able to have that discussion with God and my family,” even though as governor he’d do what “the people would have me to do.”

After the forum, McCarty highlighted the question as a key one. “One of the biggest distinctions between the three that will really matter to Republican voters is that one of them is not pro-life, and that’s Allen West,” she told me. The only other differences, McCarty noted, were in credentials and experience. “Beyond that,” she acknowledged, “they’re pretty similar.”

The two questions animating Democrat Beto O’Rourke’s challenge to the governor—how Abbott has handled last winter’s failure of the electric grid, and how he’s dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic—only received brief attention. On the question of February 2021’s “Snowmageddon,” Huffines blamed Abbott for relying on green energy sources (despite wind sources performing less poorly than coal and natural gas during the freeze). West called for weatherization of natural-gas facilities and delivered the best anti-Abbott punch of the night, telling the story of an eleven-year-old from Conroe who died during the storm and noting that the leader of a company that made $2.4 billion in profits during the blackouts cut Abbott a check for $1 million in June.

All three candidates said they opposed vaccine mandates—which Abbott, after months of Huffines’s rabble-rousing, issued executive orders to prohibit. Prather went further and dismissed all discussion of the coronavirus. “Everyone has omicron,” he said. “Look at your neighbor, kiss each other, and get it over with.”

But this was not a competition, strictly speaking, to be provocateur king, and so at the conclusion of the forum, audience members were asked to fill out straw-poll ballots. Rhodes remarked, pointedly, that this process would be “one ballot, one vote.” But as with many alleged Democratic vote-harvesting schemes, the ballots wouldn’t be tallied until much later; the group’s leaders had to travel back home first. (At press time, the results had not been released.) This audience was not a representative sample of the GOP electorate at large, though the attendees were likely primary voters; many came from local GOP groups and were sufficiently up to date on the news cycle to twice boo mentions of Republican congressman Dan Crenshaw of Texas, who recently feuded with congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia and called for more COVID testing.

The hope, for these folks, is that the trifecta of right-wing challengers will keep Abbott below 50 percent in the March 1 primary, forcing him into a runoff in May. That appears to be a long shot, given that a November poll from the Texas Hispanic Policy Foundation and Rice University’s Baker Institute found 64 percent of likely primary voters backing Abbott, against 13 percent for West, 5 percent for Huffines, and 3 percent for Prather.

Outside the auditorium, West yard signs went quickly. A few folks who gathered near Prather’s table told me they supported him because, like Trump, he’s an outsider, and, as one put it, “Abbott sucks.” Others said Huffines’s legislative experience set him apart. As the candidates greeted fans who stuck behind for pictures and autographs, McCarty told me she considered the event a success: “People love to hear the red meat and understand and be able to articulate why Abbott has to go.”

I asked her what would happen if Abbott won the primary. She responded without hesitation: “We all get behind Abbott.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott

- Allen West

- Houston