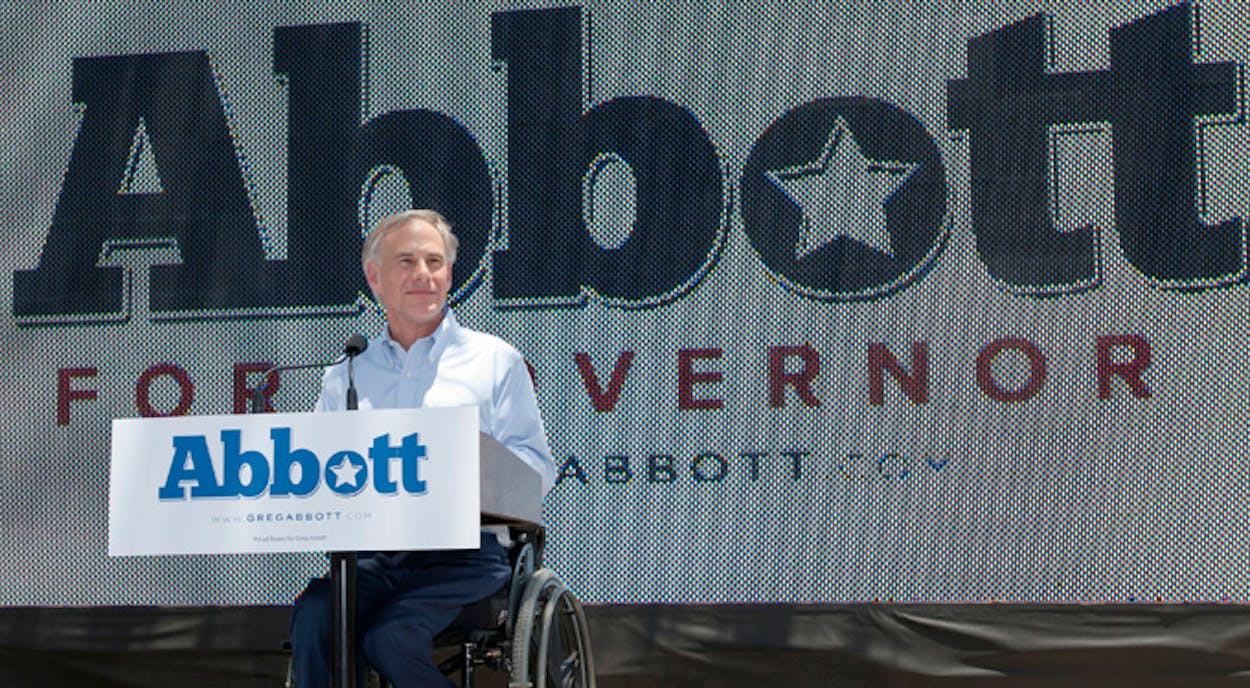

A July sun blazing high above Plaza Juarez in San Antonio’s historic La Villita provided the backdrop as a key piece of the 2014 election puzzle locked into place on Sunday: Attorney General Greg Abbott announced his candidacy for the Republican nomination for governor. “Man, I know you’ve been out here in this hot sun, and it’s hot out here,” Abbott said as he opened his remarks, wearing a blue button-down shirt with no jacket or tie. “But it’s not as hot as this campaign is about to get.” Six days earlier, Governor Rick Perry used the Holt Caterpillar dealership in San Antonio to say that he was not running for reelection next year; yesterday the city marked the start of Abbott’s campaign, which helps usher in is a new era of state politics. Not only will the governor’s race be for an open seat, but so will the campaigns for attorney general, comptroller, land commissioner, and agriculture commissioner (the race for lieutenant governor has the feel of an open seat, with Republican incumbent David Dewhurst facing a challenge in the primary from three current officeholders).

The location for the announcement was not without significance. For Abbott, the city offered a blend of the personal and the political. His wife of 31 years, Cecilia, is from San Antonio, and her parents still live in the house she grew up in. During the speech, he even pointed in the direction of a spot along the River Walk where he had proposed to her, on Valentine’s Day, and noted that they were married at Our Lady of the Lake. “Our marriage was a uniting of cultures: my Anglo heritage, and Cecilia’s Irish and Hispanic heritage,” he said. (Abbott did mix some Spanish into his speech, but he does not speak it fluently. And though his wife’s grandparents were immigrants from Mexico, her mother insisted that Cecilia speak English instead of Spanish growing up.) But San Antonio also has proven to be a powerful symbol of the Texas economy and a political battleground where the parties are locked in a fight to attract voters from the state’s booming Hispanic population, who are widely considered to have the power to shape Texas’s political dynamics in the coming years.

Abbott used the occasion to introduce himself and his life story to the crowd and to touch on broad if familiar political points: a staunchly pro-life stance, a strong rebuke of perceived federal overreach, a commitment to low taxes and keeping the economy strong, and an impassioned defense of gun rights (when speaking of his childhood, he mentioned “feeling the grip of a gun” before he spoke about playing Little League baseball or joining the Boy Scouts, and when his sixteen-year-old daughter, Audrey, was asked what her favorite thing to do with her dad is, she said hunting).

Beyond the city, the date of the announcement carried a deeper meaning for Abbott that taps into one of his campaign themes: perseverance. “My greatest fight began on this very date, July 14, 29 years ago in Houston, Texas,” he said, speaking from his wheelchair behind a low podium. “What happened that day made it highly improbable that I would even be here today to get to speak with you.” Abbott had been studying for the bar examination with a friend, Fred Frost, and later in the day they went jogging through River Oaks. That’s when a freak accident changed his life forever: an oak tree collapsed and fell on him, fracturing several vertebrae and severing his spinal cord. After a series of operations—including placing two steel rods along his spine–and prolonged physical therapy, he survived, but he would never be able to walk again. But overcame the disability to become a district judge, a member of the Texas Supreme Court, and attorney general. He has also learned to use the tragedy partly as an inspiration tale and partly as a way to disarm people by making light of it. “You know, too often you hear politicians get up and talk about having a spine of steel. I actually have one!” he said. “And I will use my steel spine to fight for you and for Texas families every single day.”

As for the critical issues facing the state, he offered few specific details. He acknowledged that “our water supplies are going too low” and “traffic congestion is getting too thick” and “our schools must do better.” So what is the answer to those problems? “We can solve those problems not by raising taxes but by right-sizing government and putting real limits on spending in Austin, Texas.”

In addition to what he said, it was worth noting what he didn’t say. There were no stories about his own religious beliefs or experience. There were no references to Perry—in fact, nothing at all to suggest his thoughts on the current governor’s administration. Instead, yesterday was a day for Abbott and his family—and a chance from them to start to explain to the voters who he is. He wasn’t even introduced by another politician or celebrity; instead, Audrey filled that role, which she will continue to do as the campaign makes stops in nine cities over the next four days.

Abbott hits the campaign trail as the unquestioned front-runner. He has locked up widespread support among the party leaders, and he has amassed a war chest of more than $20 million. He will face underdog Tom Pauken, the former chairman of the Texas Workforce Commission, in the Republican primary, but it is doubtful that any other major contender will enter the primary. That leaves two questions on the table: will a credible Democrat challenge Abbott now that the party appears to have reenergized itself around Fort Worth state senator Wendy Davis? And, given that a Democrat hasn’t won statewide office since 1994, does it really matter?

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott