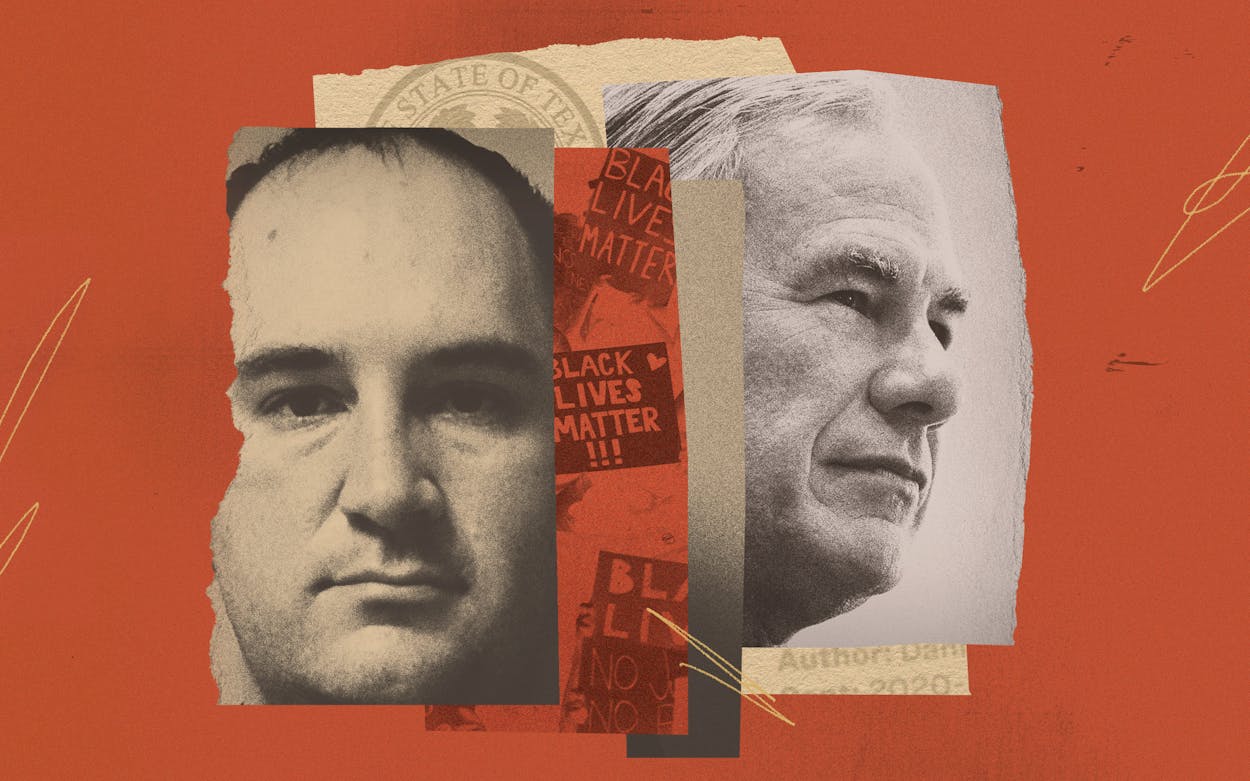

After seventeen hours of deliberation spanning a Thursday and Friday in April, a jury of Daniel Perry’s peers unanimously convicted him of murder in the 2020 shooting of Garrett Foster at a Black Lives Matter protest. One day later, roughly eighteen hours after a segment on Tucker Carlson’s prime-time Fox show show complaining about the verdict, Governor Greg Abbott promised he’d try to nullify the decision by pardoning Perry as soon as possible.

In his statement, Abbott did not raise any substantive concerns over the jury verdict. He was motivated purely by political considerations. The Texas governor has been rooting around for issues to make his congenitally dull brand more appealing to national conservatives, and this was a promising one. When he was shot, Foster was attending a protest against police violence in Austin, the sort of demonstration opposed by many right-wingers in Texas. Perry, an Army sergeant who was working as a rideshare driver that night, was the right kind of killer for Abbott to back.

“Conservatism consists of exactly one proposition,” according to a modern aphorism. “To wit: there must be in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, alongside out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.” Foster, an Air Force veteran, was legally carrying a rifle. He would be the man whom the law binds but does not protect. Perry was an Uber driver who intentionally drove into a crowd of demonstrators, saw Foster approach with his rifle, and shot him five times with a gun Perry was also legally allowed to carry, later claiming the right to self-defense. He would be the man whom the law protects but does not bind.

The case concerning the shooting of Foster was not a he said, he said. In his statement to detectives following the shooting, which was videotaped and shown to the jury in full, Perry didn’t say that Foster pointed his gun at him. No witnesses said that Foster had been aiming at Perry, either. (Perry had told police at the scene, and later maintained, that Foster had raised the barrel of his gun, though that is disputed by witnesses.) Instead, Perry, who said he’d been distracted before he turned into the path of the protest, told a detective he “didn’t want to give [Foster] a chance to aim at me.” So Perry shot him repeatedly with a .357 revolver through the window of his car.

Immediately, Perry became a cause célèbre to right-wingers who argued that he had put down one member of a dangerous coalition bent on destroying the city. In their telling, Foster had been aiming his gun at Perry, who had narrowly escaped with his life. José Garza, the Travis County district attorney who brought the case, became a “[George] Soros prosecutor” who was a “cancerous tumor” and an “evil, subversive, dangerous Marxist,” according to one dyspeptic commentator who was retweeted by Texas GOP chair Matt Rinaldi. Abbott implied Garza was a rogue prosecutor, without clarifying what path he and others had gone rogue from. Republican congressman Chip Roy, who represents a district that includes a slice of Austin, argued that the jury verdict was a decision “in favor of the lawless over those defending against the lawless.”

The night of the conviction, Tucker Carlson called it a “legal atrocity.” He told his audience that he had asked Abbott to appear on the show to ask him if he was considering a pardon and that Abbott had declined. He scorched the governor for this: “So that is Greg Abbott’s position—there is no right of self-defense in Texas.” Carlson’s opinions served as marching orders for many in the GOP, and nobody could afford to get on his bad side.

The problem: The governor of Texas, unlike the president, does not have the power to issue pardons on a whim. He can only act on recommendations from the supposedly neutral Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles. So Abbott, who did not respond to requests for an interview with Texas Monthly, wrote in a statement that he was asking the BPP, most of whose members he had appointed, to look into the Perry case and produce a recommendation as quickly as possible. The move surprised former pardon officials in the state, but Abbott bought himself two and a half weeks of goodwill from Carlson.

The governor’s statement made criminal lawyers in Texas go a little nuts, and rightly so—this is not how the system is supposed to work. The trial was not broadcast, and Abbott did not attend. He does not know more about the evidence than the jurors, and he has made no effort to explain what they got wrong. Abbott is a former Texas Supreme Court justice, generally thought to have legal acumen. He must have known he was jumping the gun.

In the week after he made clear his intention to pardon Perry, Abbott got to learn a little more about the man he was backing. The court made public dozens of pages of Perry’s text messages and internet history, some of which the jury had considered. Perry told a friend he had killed a homeless man “by accident,” searched in a web browser for “good chats to meet young girls,” and called Black protesters “monkeys flinging s— at a zoo.” He shared “white power” memes and had fantasized to others for years about being able to kill Black and Muslim protesters with impunity.

Not long before the incident in which he shot Foster, as Black Lives Matter rallies were being organized in cities across Texas, Perry told a friend that he “might have to go to Dallas to shoot looters.” Then he seemed to realize he might not have to leave home. “I might have to kill a few people on my way to work,” he told the same friend. “Catch me a negro,” the friend later texted. “That is what I am hoping,” responded Perry. Far from an upstanding Army vet simply trying to protect his person and property, Perry was an off-brand Travis Bickle, musing about washing the scum from the streets.

By seeking a pardon for Perry, Abbott is acknowledging the growing appetite in some quarters for vigilante violence. Major political forces in America that identify themselves as being in favor of “law and order” have developed a highly conditional view of what law and order means: law for thee, not for me. A few weeks after the Perry shooting, Kyle Rittenhouse, then seventeen, killed two protesters in Wisconsin, having brought his rifle to protect property. Rittenhouse was acquitted on self-defense grounds, but during his trial he became a hero to some, who celebrated the shooting of protesters long before a jury determined that force could be justified. The real questions—should a teenager have brought a long gun to a place of civil unrest to try to “restore order,” and should the law have empowered him to do so?—became obscured.

There is a similar question in the case of Perry. The killing of Foster took place on Congress Avenue, in view of the Texas Capitol. Policies set in that Capitol make shootings such as these more likely. State government has blessed a state of affairs in which many protests and episodes of civil unrest are going to draw armed men and women on both sides—some with high-powered rifles, some with hidden handguns. In an environment where passions run high, shootings aren’t unforeseeable. They’re inevitable.

In his statement on the Perry conviction, Abbott bragged about “stand your ground” laws being strong and uncompromising in Texas. Such laws rest on a principle that may initially seem simple: if threatened, you can legally use deadly force. But if two men are legally carrying guns and stumble into a confrontation, figuring out which one has the “right” to self-defense can become a fairly arbitrary matter, no matter what the law says. For folks such as Carlson, Perry was the one with a right to self-defense because he was “the good guy.” Foster, who saw a car drive into a crowd he was seeking to protect, is “the bad guy.”

For some Texans, vigilante justice is a feature, not a bug, of lax gun laws. Rittenhouse, a popular figure in the GOP who recently headlined a right-wing event in Texas, joined Carlson in saying Perry should not have been convicted. Abbott has only approved seventeen pardons in the past three years, all for lower-level offenses. (Abbott’s predecessor, Rick Perry, averaged nearly sixteen a year during his fourteen-year tenure.)

Concurrently, Abbott has spent a significant amount of his political life railing against alleged lawlessness in Texas cities. Bail reform efforts have resulted in murderers walking the streets, he argued in a State of the State address. In turn, Abbott’s allies have responded to crime by undermining local officials and claiming power for themselves. State officials have come to argue that city councils cannot be trusted to set rules and budgets for local police departments. They also say local prosecutors, often elected overwhelmingly, should not be able to use discretion to handle cases with lenience and instead should defer to Abbott and the Legislature’s preferences. Now the standard appears to be that jury verdicts can be nullified by executive fiat.

“Five minutes ago, he wanted [Travis County DA Garza] to prosecute more murders. Now he’s mad about it and calling it abuse of his office,” says Scott Henson, a longtime criminal justice reform advocate in the state. “I think we need more clemency, not less, and I don’t think what he’s doing is inappropriate per se. It’s just wildly inconsistent with all past statements and actions on the topic and seems opportunistically political.”

All the while, statewide officials have repeatedly acted to insulate themselves from legal challenges. The Legislature approved putting a constitutional amendment on the ballot in 2015 that enabled statewide officeholders to claim residence outside of Austin—letting those who face criminal charges use the same tricks that have kept Attorney General Ken Paxton from facing his felony indictment for securities fraud for nearly a decade. Paxton’s wife, Angela, a state senator, famously attempted to make the kind of securities fraud of which her husband was accused legal. And in 2015 the Legislature took jurisdiction over public corruption cases from the Travis County DA’s Public Integrity Unit, which had been independent of the Lege, and gave it to the Texas Rangers, which is part of a state agency controlled by the governor. When lawmakers inside his party challenge the ethical propriety of Abbott’s actions—of, say, giving his major campaign donors positions of public authority—the governor punishes them harshly.

There is no grand principle of justice that the governor is expressing. There is only this: the law must bind my enemies and not my friends, and it must protect my friends but not my enemies. That approach may be an inevitable result of one-party rule, but it also, historically, ends pretty badly for everyone.

It was hard not to feel a sense of foreboding about what Tucker Carlson might tell the governor to do next. But we didn’t have to worry about that for too long. On April 24 Carlson, the man who could frighten the nation’s most important red-state governor, lost his bully pulpit when he was unceremoniously fired from Fox News.

Carlson may be issuing fewer demands in the future, but the ideologies he helped bolster in the party will live on. He was “a good friend and a voice for millions,” Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick said upon his dismissal from Fox. “He will be greatly missed.” Texas GOP chair Rinaldi said there was “zero reason to watch Fox News now.” Abbott, notably, was silent on the matter, and his board of pardons has no power to overturn Carlson’s firing. Perry may get a reprieve, but other instruments of justice remain intact.

Christopher Hooks is a journalist based in Austin.

This article appeared in the June 2023 issue of Texas Monthly. It originally published online on April 10, 2023, and has since been updated. Subscribe today.

Image credits: Perry: Austin Police Department via AP; Abbott: Brandon Bell/Getty; Protest: Cal Sports Media via AP; Governor’s Seal: Michael M. Santiago/Getty

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Black Lives Matter

- Greg Abbott