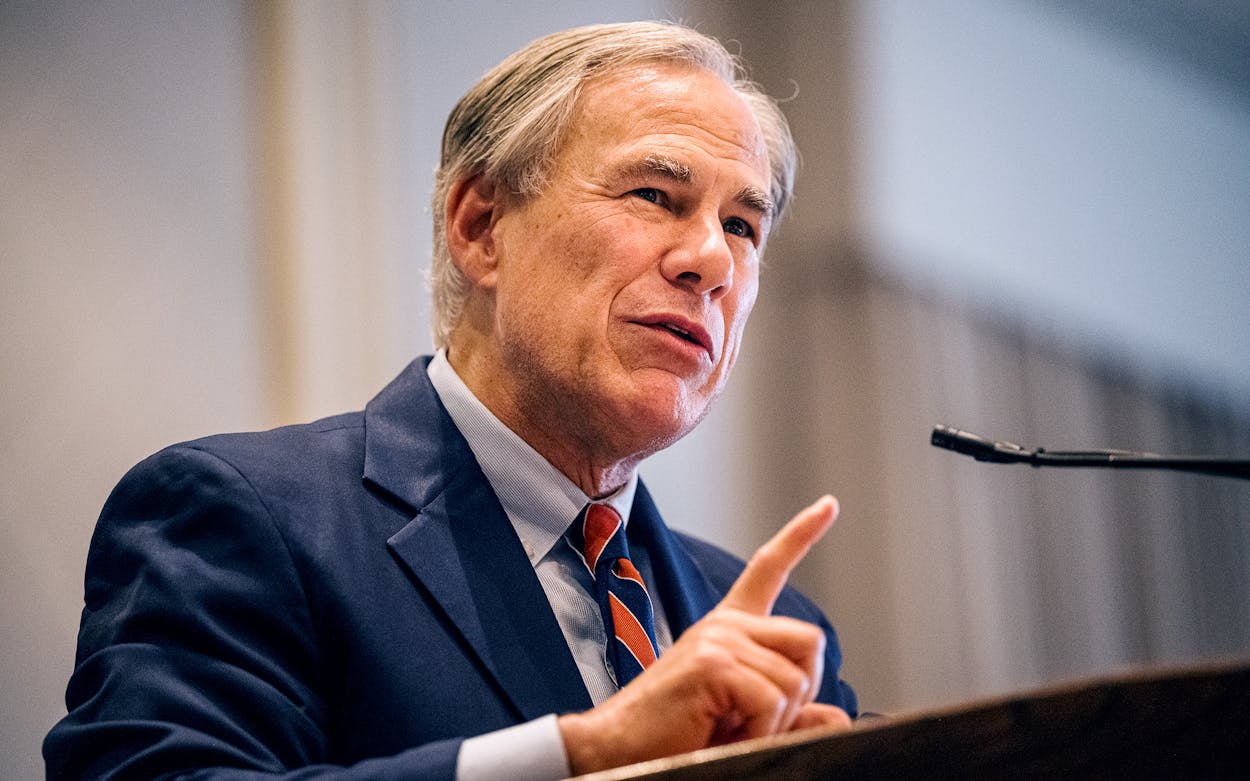

If you watched Governor Greg Abbott’s State of the State address on Thursday night, you were treated to what amounted to an extended political ad, 25 minutes of made-for-TV messaging for a third-term governor who may be eyeing a White House bid. Traditionally, the governor gives the State of the State address at the Capitol, where lawmakers gather to hear what the state’s top executive would like them to do during their brief, every-other-year legislative session. The press and invited members of the public attend. The setting—the seat of democratic governance in the Texas capital—makes more than just symbolic sense.

And for his first three State of the States, Abbott did just that: he laid out his legislative priorities at the Lege. In 2021, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the State of the State was held in Lockhart. But this year, he tweaked the format even more. Instead of at the Capitol, he gave his speech in San Marcos, thirty minutes south of Austin, at Noveon Magnetics, the nation’s only manufacturer of rare-earth magnets. The press wasn’t allowed to attend. Cellphones were banned. And attendees—including “select members of the San Marcos business community”—were originally expected to sign nondisclosure agreements. The overall effect was of the governor speaking from a hermetically sealed safe space.

The television production itself only added to the sense that Abbott was campaigning. Nexstar Media Group televised and streamed the event, but the hour of programming was far more than just a camera filming a powerful man talking. C-SPAN this was not. Nexstar displayed B-roll during Abbott’s speech, essentially giving the governor permission to produce a political ad. At one point, the viewers saw Fox News–esque footage of migrants lined up at the border as the governor spoke angrily of Joe Biden’s “open-border policies.” The venue itself was a bit of a head-scratcher, at least until Abbott started talking about the Chinese choke hold on rare-earth metals, a somewhat unusual foray into geopolitics for a governor whose foreign policy interests usually begin and end at the Texas-Mexico border.

The main news value of the State of the State is the governor’s unveiling of his emergency items for the Lege. Under the state constitution, lawmakers can’t pass legislation until after 60 days of the 140-day legislative session, unless the governor has deemed it an emergency. This year, Abbott laid out seven emergency items—cutting property taxes, ending COVID restrictions, “education freedom,” school safety, border security, scrapping “revolving-door” bail policies, and prosecuting fentanyl-related deaths as murders.

Most of these are no-brainers for a Republican governor of Texas. Cutting property taxes, securing the border, beating up on big-city Democratic DAs—these have been staples of Abbott’s political platform for years. Ending COVID restrictions is a sop to his critics on the right, though some will surely declare the effort too little, too late.

In some cases, Abbott offered few details on which specific policies he prefers. For example, he didn’t explain what “school safety” measures would entail—no doubt a frustrating omission for the families of victims of the mass shooting at Robb Elementary in Uvalde just nine months ago. At one point, Abbott mentioned pay increases for workers at nursing homes before abruptly pivoting back to perhaps more comfortable terrain: how Harris County’s activist judges are “literally killing people” because of lenient bail policies.

Abbott has often favored piddling proposals—anyone think his two-session gambit to bring ethics reform to Austin made the Capitol a paragon of virtue?—but his backing of vouchers may be one of his most consequential decisions yet. Tonight, as expected, he gave enthusiastic, if somewhat vague, support for “education freedom” and “school choice”—euphemistic terms often understood to refer to schemes that shift public dollars to private institutions. Notably, Abbott did not use the word “vouchers,” which doesn’t poll well and riles many rural Republicans, a bloc that has prevented a voucher program from passing in Texas for decades.

First Abbott bragged on Texas public schools, asserting that per-student funding is at “an all-time high.” (In fact, the state’s main contribution to Texas public schools, the per-student basic allotment of $6,160, has been stagnant since the 2019–20 school year and trails the national average. Factoring in record inflation, funding for public schools has been sliding in the last several years, and lawmakers seem to have little appetite for increasing it.) Being good at math may be optional for an aspiring national politician, but impersonating Ron DeSantis is not. Thus, Abbott was soon talking about the source of all evil in the world: Big Woke.

The governor doesn’t have a wide-ranging emotional register, but it seems like maybe he’s been practicing, because he sizzled just a bit. “Schools are for education, not indoctrination,” he said, looking angrily at the camera. “Schools should not push woke agendas, period.” This was all prelude to his main call to action: designating “education freedom” as an emergency item. As best I can tell, that would translate, policywise, into support for what Abbott termed “state-funded education savings accounts.” ESAs are voucherlike programs by which public dollars are directed to parents to spend on private schools, often in the form of debit cards. Critics argue that any voucher or voucherlike policy will impoverish the public school system on which the vast majority of Texans rely. Perhaps anticipating this critique, Abbott pledged that “all public schools will be fully funded for every student.” He did not elaborate on what “fully funded” meant.

But he didn’t really need to. When given a chance to offer a rejoinder to Abbott live on air, the Democrats had only tepid tea. Their formal response to the speech was a video montage of a dizzying number of elected officials offering a dizzying number of talking points, set to upbeat music. (My TM colleague Ben Rowen said it felt like an in-flight safety ad.) On a talking-heads panel after the official rejoinder, Senator Royce West, a Democrat from Dallas, spelled out a few specific policy proposals. But after thirty years in the Senate as a Democrat, West is a bit battle-hardened. He volunteered that Republicans had the “right” to go forward without Democrats on some important issues. If his party wanted more of a say, well, they would “have to start winning elections.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Texas Legislature

- Greg Abbott