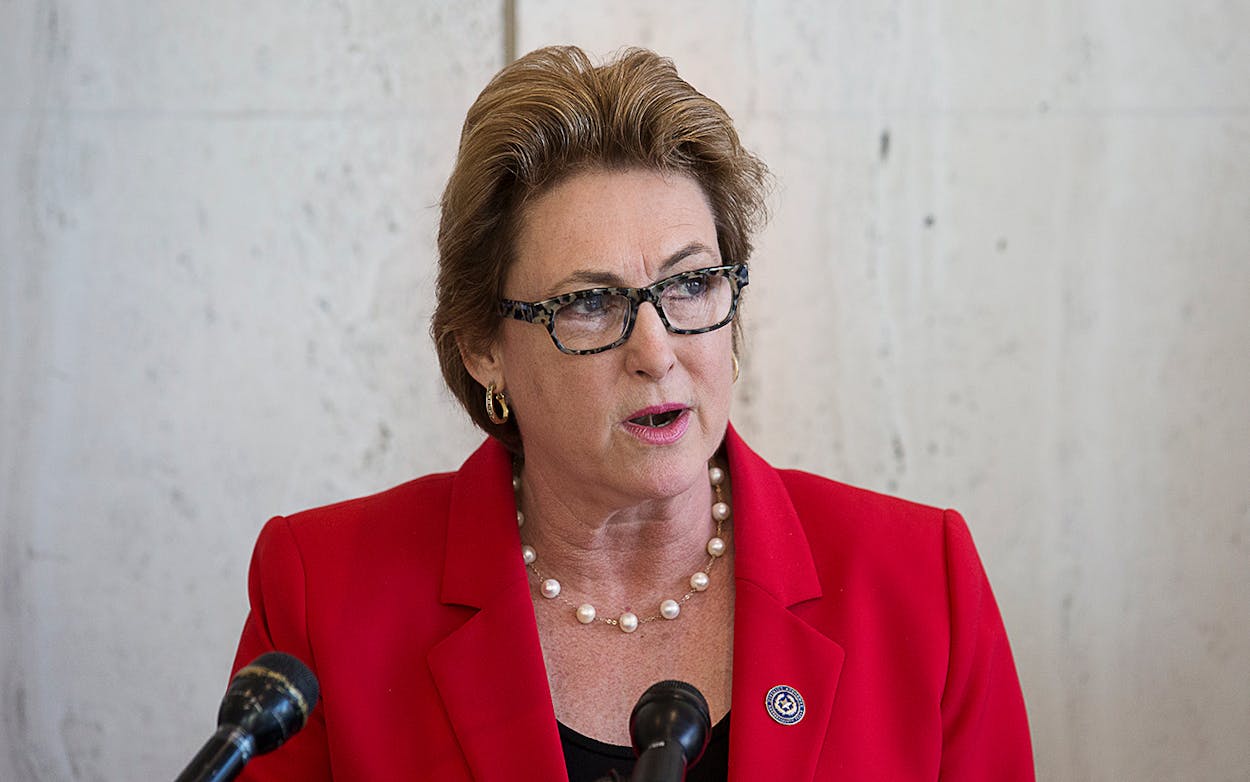

Life has been moving pretty fast for Harris County district attorney Kim Ogg. Just four years ago she rode to victory on a bold criminal justice reform platform, knocking off scandal-plagued incumbent Devon Anderson, a law-and-order Republican of the type Houston had grown familiar with over the decades. Ogg joined a cadre of so-called “progressive prosecutors” across the country who were going to reform the cash bail system, stop arresting people for marijuana possession, and end long-standing racial disparities in prosecutions.

Now Ogg is being challenged from the left in the March 3 Democratic primary by two of her own former prosecutors, who say she broke her campaign promises. (Early voting is now under way.) Prominent liberal organizations that backed Ogg in 2016 have defected to endorse her opponents. Her requests for dozens of new prosecutors have been repeatedly rejected by a Democratic-controlled commissioners’ court.

“She campaigned on being this progressive change-maker,” said Audia Jones, a former assistant DA who resigned in December 2018 after four years in the office, and is widely considered Ogg’s top challenger. “I was excited to have her as our new boss. But then she did pretty much a 180 from what she promised. I could no longer be a part of that.” Jones grew up in Connecticut and played Division I basketball at the University of Rhode Island before moving to Houston to attend law school at Texas Southern University. A member of the Democratic Socialists of America, the largest socialist organization in the country, which saw staggering growth after Trump’s election, Jones was recently endorsed by Bernie Sanders.

Ogg’s other major challenger, Carvana Cloud, led the family violence and special victims bureau under Ogg before resigning in late 2019 to enter the primary. “I was a strong supporter of Kim on the campaign trail in 2016,” Cloud said. “I wrote checks, I knocked on doors, I used my own resources to give her street cred in my community. But once I started in her office, I quickly realized that my vision for reform was way more expansive than hers.” (The third candidate in the race is Todd Overstreet, an extravagantly mustachioed defense attorney whose criticisms of Ogg have been significantly milder. Vying for the Republican nomination are former prosecutors Lori DeAngelo and Mary Nan Huffman, joined by perennial candidate Lloyd Oliver, once described as a “barnacle on the body politic” by local progressive blog Off the Kuff.)

Jones and Cloud believe Ogg has been far too timid in pursuing criminal justice reform. They question her decision to continue seeking the death penalty in some murder cases. They say her much-hyped reforms, including marijuana and mental health diversion programs, aren’t doing enough to stop low-level arrests. And they criticize her for rallying last-minute, and unsuccessful, opposition to a legal settlement that eliminated cash bail for most low-level offenses—a major step toward ending mass incarceration—despite saying she supported bail reform while campaigning in 2016. The county is now facing another lawsuit challenging its practice of jailing felony defendants, many of them charged with nonviolent drug crimes, for weeks or months if they can’t afford bail. With the county currently in negotiations to settle the lawsuit, Ogg has remained publicly noncommittal other than to say she has “concerns about the public safety impact.”

Time was when a Harris County DA would think twice about adopting even the most modest reforms for fear of being tarred by conservatives as soft on crime. But thanks to changing demographics and an anti-Trump backlash, the local Republican party is on the ropes. Hillary Clinton carried the county by 12 percentage points in 2016, helping sweep in Ogg and Democratic sheriff Ed Gonzalez. In 2018, with Beto O’Rourke at the top of the ticket, Democrats won every county-wide race and secured a majority on the commissioners’ court. These days, the only challenge a Democratic county officeholder need fear is a primary opponent. And those primary opponents are increasingly emboldened.

“The sands continue to shift in the politics of the Democratic party,” said University of Houston political scientist Brandon Rottinghaus. “A platform that seemed progressive four years ago now seems outdated and not ambitious enough.”

Case in point: Ogg’s marijuana diversion initiative, a centerpiece of her 2016 election campaign. It proved so popular that Anderson, the Republican district attorney, enacted a watered-down version. Fully implemented in 2017 once Ogg took office, the program allows offenders caught with less than four ounces of weed to avoid a criminal charge if they pay $150 to take a four-hour cognitive decision-making class. There were key exceptions—nobody caught in a school zone or with “intent to deliver” was eligible—but the plan sounded good on paper.

The program quickly hit a snag: people weren’t taking the class. Of the 12,691 individuals diverted into the program through the end of January, only 6,750 have actually completed the course, according to numbers supplied by Ogg’s campaign. Despite fee waivers for poor defendants, the “number one reason” for the low numbers, according to Ogg’s chief of staff, was the $150 price tag. Alec Karakatsanis, founder of the Washington, D.C.-based Civil Rights Corps, calls diversion programs like this an example of “net-widening”: “By charging people fees you encourage more and more arrests, because you know you don’t have to actually prosecute all those cases. What ends up happening is that it encourages more people to be brought into the system.”

Ogg’s office has continued the marijuana diversion program even after the Texas Legislature changed the legal definition of marijuana last year to allow the possession of hemp and hemp-derived products like some CBD oils. Because most Texas crime labs, including Harris County’s, don’t possess the equipment necessary to distinguish hemp from marijuana, the Legislature’s move led prosecutors across Texas to stop prosecuting minor marijuana cases. When asked why Ogg hasn’t joined with her peers in most of Texas’s urban counties, her campaign spokesman Alan Bernstein said the charges “could be prosecuted if and when police agencies provide the technology to the lab.”

For Audia Jones, that’s not good enough. She wants to fully decriminalize marijuana by refusing to accept charges from police departments. “When you’re talking about scarce prosecutorial resources and scarce law enforcement resources, we need to be focused on violent offenders,” Jones said. She also wants to decriminalize sex work by prosecuting human traffickers rather than their victims.

At a recent fundraiser in Houston’s Fifth Ward neighborhood, Ogg seemed incredulous that her criminal reform bona fides were being questioned “I have confidence that the community is satisfied with the rate of progress we’re making,” she said. As for her challengers? “I think they’re manufactured. I think it’s a few people very interested in changing out liberal Democrats for even more liberal Democrats. There are folks who are funding local, allegedly grassroots organizations. I just don’t think it’s organic.”

In 2016 Ogg was endorsed by the Texas Organizing Project—partially funded by billionaire George Soros, who also bought $1.4 million in ads to help elect Ogg—and the Houston GLBT Political Caucus, the oldest gay and lesbian rights organization in Texas. Both are supporting Jones this time. The GLBT Caucus defection was an especially stinging rebuke for Houston’s first openly gay district attorney. Ogg blamed the loss on a “takeover by the socialists,” and called the current primary a proxy battle between the Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders wings of the party. “I don’t think it’s healthy. I don’t like it. I want this primary to be over so we can get on with the progress we’ve been making.”

And while she gets slammed from the left for being an overzealous prosecutor, some in law enforcement blame her reforms for supposedly making Houston less safe. The Houston Police Officers’ Union has called her “the most criminal-happy district attorney in history.” Although no public polling exists for the race, Rottinghaus said it seemed likely to go to a runoff between Ogg and Jones.

One challenge that criminal justice reformers face, Rottinghaus said, is trying to change the popular image of DAs. “Prosecutors are supposed to be these hard-nosed, cigarette-stubbing, coffee-swilling attorneys who are putting criminals behind bars. A progressive prosecutor seems to be a bit of an oxymoron. But they’re becoming more common in these big urban areas.”

As for Kim Ogg, her campaign website sums up her message to voters with this: “Texas’ most progressive District Attorney is Kim Ogg.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy