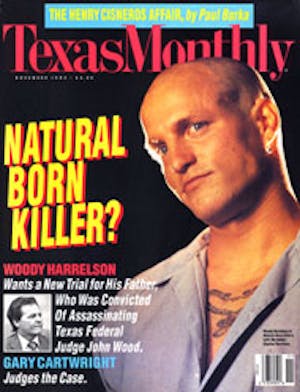

This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It is December 10, 1992. Henry Cisneros is calling Linda Medlar, his former lover, from the car phone of his Jeep. Their relationship—which has been public knowledge since he confessed it at an impromptu meeting with reporters in 1988—is over, but he has been sending her money, a lot of money as it turns out, and now the trap has closed around them, because the former mayor of San Antonio wants to return to public life. He might be named by Governor Ann Richards to fill the U.S. Senate seat left vacant by Lloyd Bentsen’s appointment as Secretary of the Treasury, or he might be named to a Cabinet post himself, but either way there will be questions about his personal life, questions about whether the payments are hush money—and maybe, he is thinking, he shouldn’t take either position. Unknown to Cisneros, Medlar has been taping his calls since 1990.

HE: The financial [arrangement] of the past doesn’t go down, and they—well, I don’t want to talk about it on this phone.

SHE: Yeah. Why did they have to know about that?

HE: ’Cause they would. It’s pretty obvious when they probe [your] visible means of support.

SHE: And what about the Senate?

HE: Well, if it’s going to be a problem in one, it’s a problem in the other.

SHE: Not necessarily.

He: . . . My brother called yesterday and said, “You are a jerk. You ’re stupid. I mean, if you pass on something like that, you should just go out on a farm and vegetate. . . .”

SHE: I don’t know, Henry. I think it’s manageable.

HE: You do?

SHE: Yeah, I do. I think you’re doing what you do on everything that you have done in your entire life, and that is putting the absolute worst, worst, worst-case scenario on it.

The transcripts of the Cisneros-Medlar phone conversations are sad and compelling documents. Even Cisneros himself, with characteristic openness, acknowledges their power to engross. When I told him, during an interview in Washington, that I had read them like a book I couldn’t put down, he said, “They’re like one of those two-person plays. Some of the dialogue is pretty good.”

Every page conveys the pain of life’s dirty tricks—hopeless love, unrealized ambition, lost innocence, the poisonous influence of money—and the plot moves inexorably toward its unhappy ending. As the drama opens, Cisneros and Medlar have given up their careers in politics (she was his fundraiser) for quieter pursuits in separate cities—Cisneros in San Antonio, Medlar in Lubbock. But when he is drawn back to the public arena, she realizes that he will no longer be able to send her money, as he has promised to do.

SHE: I don’t know that you understand. After you go to Washington, Henry, I may never hear from you again. You understand, I don’t know what’s going to happen after you go to Washington, whether it’s the Cabinet or the Senate.

HE: We will work all that out. I mean, just don’t jump to these incredible conclusions. Really, I mean, I just got through going to the bank for the precise purpose of dealing with this matter about—you know, what you are concerned about—and every day I do something on some aspect of it, and there’s just not that much reason for anxiousness, you know.

She: Well, I’m sorry I can’t agree with you.

Under financial pressure, whatever affection and hope for reconciliation they might have had begins to fade, conversation by conversation, until in the end only suspicion is left: Medlar’s, that she will be cut off; Cisneros’, that he is being taped. Both, of course, are right. But the story does not end with the last transcript. On July 29 Medlar filed suit in Lubbock, charging that Cisneros had broken an agreement to pay her $4,000 a month. Then she sold a batch of tapes—many more have yet to be transcribed—to the syndicated television show Inside Edition for $15,000. After the tapes were played on national TV, reporters questioned whether Cisneros had misled the FBI, which checks the background of Cabinet nominees, about his financial arrangement with Medlar. Now the FBI has reopened its investigation, and only time will tell whether Cisneros will be able to remain as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

The transcripts reveal, as almost nothing ever has, the intimate character of a nationally prominent public figure. The closest parallel is the Watergate tapes, but Cisneros’ conversations are very different from Nixon’s. The transcripts, which were distributed to the news media by Inside Edition and by Medlar’s attorney, cover fifteen conversations, all but one of them during the winter of 1992 and 1993. They total 175 single-spaced typewritten pages. In all those pages, Cisneros’ language is remarkably free of crudity. He doesn’t curse. He doesn’t gossip. He never has a harsh word for anyone but himself; the closest negative thing that he has to say about anyone is that Bill Clinton is indecisive. (Mr. Pot meets Mr. Kettle.) He is remarkably nonjudgmental about people whom he could well be angry with: Ann Richards, who does not choose him for the Senate; Phil Gramm, whom Medlar says has approached her for information about Cisneros; his business partners, who are feuding; his wife; and for that matter, Medlar, who makes occasional veiled threats.

She: I’m not trying to hold you down, Henry.

He: If you do, just do it. Just tell me, “Henry, I’m not going to let you do this. I have a potential to destroy you any time I want.”

She: But I’m not going to. I never have, so why would I do it now, Henry?

Cisneros betrays no cynicism toward public service. In fact, he tends to launch into speeches, as if he were talking to the Lions Club instead of a lover.

If . . . what I decide to do is go back into the pure public service business, then it would have to be something truly from the heart, and in that case, what I do is cities, and if [Clinton] were to say, “I want to do HUD differently, it’s not just housing but it’s really poor urban neighborhoods and riot-torn areas of Los Angeles and the South Side of Chicago and the Bronx, and that’s a cause worth doing”—but my guess is he probably has a black mayor for that. But I’m an urban planner by training, education. I have been a mayor. I care about those things, and that’s something I could get up every morning and say, “I’ve got work to do, you know. I’ve got to get people together on decrepit schools and blighted neighborhoods and so forth.”

The worst that might be said of him is that he doesn’t volunteer the whole truth to the FBI. He gives no hint on the tapes of ever having acted unethically or illegally in office, and when Medlar occasionally suggests otherwise, he promptly and vigorously denies it.

“Absolutely not,” he responds when Medlar says she was told that he used campaign cash to pay off his credit card bills. “You think that’s true?” Then, when Medlar asks how many other people might have heard the same story, he says, “I don’t have any idea, but there is no truth to that. I never, ever, ever have used public money for private purposes, ever.”

In short, the intimate Henry Cisneros comes across pretty much as the public Henry Cisneros did: clean, nice, perhaps too nice, not like a politician at all. And that, finally, is what is so revealing: The transcripts solve the mystery of why Henry Cisneros decided in 1987 not to run for governor of Texas, why he decided in 1988 not to run for another term as mayor, why he didn’t want to be U.S. senator in 1992, why he never quite lived up to the promise so many people had seen in him. He didn’t have the hard edge, the toughness, the single-minded ambition that is necessary to succeed in politics. He was indeed too nice to others—and too hard on himself. As Linda Medlar so perceptively observed, he always put the worst-case scenario on his own future.

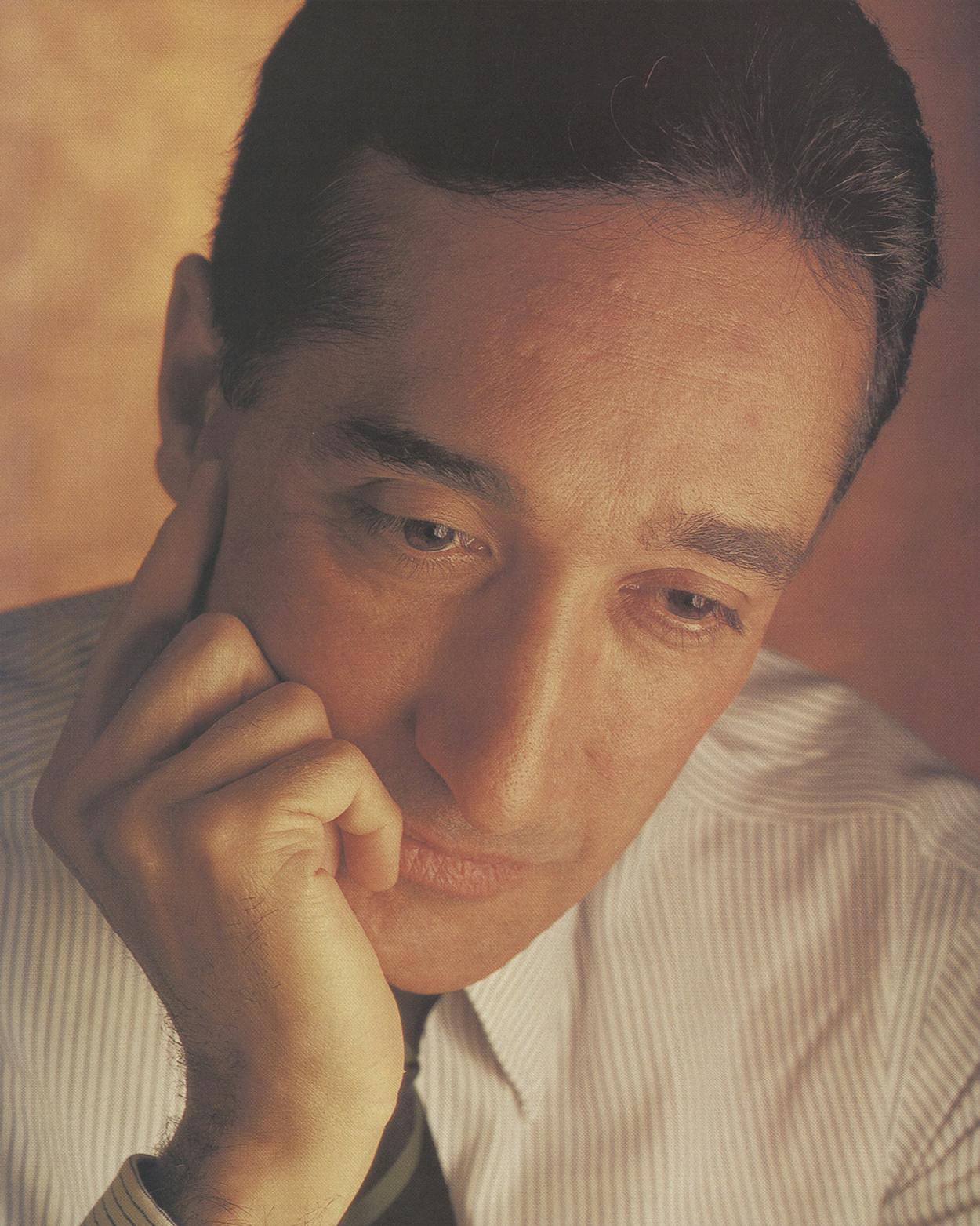

On a nippy night in October, just hours after Secretary of Agriculture Mike Espy resigned under a cloud of scandal, Henry Cisneros boarded a northbound Amtrak Metroliner and headed for Philadelphia. He looked lankier and leaner than ever, still youthful at 47. Already there was media speculation that he would be the next member of the Clinton Cabinet to quit, but he was totally upbeat as the train sped through the countryside.

“Yesterday I worked on homelessness,” he said. “Today it was home ownership. Tonight it’s youth without parents, young males without fathers.

“I’ve seen things that you wouldn’t believe could exist in the United States of America,” he said, turning his hands sideways and bringing them downward in crisp planes, like short karate chops. “People living in the subway tunnels in New York. They were covered with soot. The light was so dim we had flashlights. Down in the lowest tunnels, they’re called the mole people. In Chicago you can drive for two miles and never leave the shadow of a sixteen-story housing project. No men live there, none. It’s all single mothers.” Chop, chop, chop.

“Who ever thought that high-density projects were a good idea?” I asked him. Cisneros launched into a long discussion of housing policy. Poor people came north looking for jobs. High-rises were cheap. The policy hadn’t failed; times had changed; now there are no jobs; there are only guns and drugs. Baltimore rolled by, then Wilmington. It sounded hopeless to me, and I said so.

“Oh, no,” Cisneros said. “I’m very optimistic.” And off he went again: outreach, treatment, home ownership . . .

“What do you mean, you’re optimistic?” I asked him. “In the transcripts, Linda says that you always put the worst-case scenario on everything.”

The chopping stopped. “Only about myself,” Cisneros said. “I have always had a very conservative estimate of my own prospects.”

I thought back to early 1987, when Cisneros was on top of the political world. The two events that would change his life—the affair with Medlar and the birth of his son, John Paul, with two chambers missing in his heart—were still weeks in the future. Texas was in the throes of the oil bust, but San Antonio had the healthiest economy in the state. He was rebuilding downtown—new hotels, a new mall, eventually the Alamodome. More important, he had changed the city’s psychology. Because he preached economic development and a rising tide that lifted all boats, instead of civil rights and ethnic separatism, the Anglo business establishment embraced his message that San Antonio’s future depended upon improving the prospects of the city’s large Hispanic population. He was the bridge builder that the city—and the state, and the country—needed, and it was not too farfetched to imagine him as governor of Texas in 1990, and then, after overseeing the state’s economic recovery, the Democratic nominee for president in 1996 or 2000: the perfect candidate for the new century. And when any ambitious politician should have been thinking about running for president, what did Henry Cisneros see in his future? “I think I ought to run for comptroller,” he had told me that spring. “I’m not sure that the public is ready for a mejicano governor.”

The train began to slow for Philadelphia. The lights of the city filled the window. “Didn’t you realize how popular you really were?” I asked him.

“I always thought it could blow up at any moment,” he replied. “Maybe that’s what comes of growing up poor and Latino—never thinking that it could last.”

I had one last interview with Henry Cisneros while he was mayor. It took place over breakfast on a Sunday morning late in 1988, after the romance with Medlar had become public knowledge and he had opted not to run for reelection. I wanted to know what his political plans were. He laughed and said something like “What I’m interested in right now is learning more about country music.” Politics was not on his mind at all. The thought that he carried the hopes of millions of people—Anglos as well as Hispanics who saw in him the proof they so desperately needed that the American dream could still work—was a burden to him rather than the greatest asset a politician can have. “That’s their destiny for me,” he told me. “It’s not my destiny for me.” Then he picked up a knife and balanced it between the rim of his teacup and the edge of the sugar bowl. “All the pressure,” he sighed, “is on the bridge.” I left that breakfast convinced that he was running from public office rather than for it.

When he was in top form, Cisneros was a great, natural politician. He spoke not to people’s fears but to their hopes. He could make them believe in his vision of the future. Like Barbara Jordan, he had the ability to make all kinds of people feel proud of his success. But the transcripts reveal that he also harbored an ambivalence about politics that diminished and ultimately destroyed his ambition. He considered himself a public servant, not a politician, as though one could not be both—and when he downgraded the value of being a U.S. senator, Medlar called his hand.

He: The issue is, What have you got when you win. You know, do you have something that is worth doing, or are you just there because it is prestigious and because . . . people expect it of you and so forth, as opposed to real core reasons like really helping people. I don’t mean just thinking or talking about it or making speeches about it or pretending.

She: And what do you think?

He: I think there is a lot of that job that is pure politics—fundraising, $10,000 a day on the average, and it’s—

She: Henry—

He: Like picking federal judges, you know, like deciding between three young, ambitious people as to who is going to be a federal judge.

She: You know, I have a real problem with this. I have a real problem with the way you are stating it. You have three people and you know darn well that federal judges make a difference and you have the ability to choose a person who can make a difference one way or the other. And you don’t think that’s important.

He: No, I think it’s important.

She: But, I mean, you are talking about that being politics as opposed to anything to do with governing or policy.

Medlar is often more shrewd than Cisneros about politics. When he says the times have changed about politicians and love affairs, she says, “The deal isn’t over with Clinton. He may be on a honeymoon now, but it’s not going to stay that way.” When Cisneros tells her, “I don’t particularly want to be in the United States Senate,” she says, “No, you want to be governor.” When he says that appointees are subject to less intense opposition than candidates, she reminds him of Clarence Thomas and John Tower.

It is apparent from the transcripts that Cisneros doesn’t really know what he wants. He would like to be Secretary of Commerce, but he won’t ask Clinton for it. He doesn’t want to be Secretary of Transportation, but after he chooses HUD, he keeps wondering if he made the wrong choice. He says that he has to return to public life or he will “die on the vine,” but then he says:

This is real hard. This is real hard. I honestly wish I wasn’t doing [HUD] for a lot of reasons. One, the department is in a whole lot worse shape . . . than I thought. Two, it’s going to be a thankless, thankless, thankless job. Three, it’s going to be real hard on John Paul, uprooting and all that stuff, being away from that big support system he’s got. . . . I wish I’d had the presence of mind to do what I said I was originally going to do, which is to say no.

In the tapes, Henry’s role is that of a Hamlet tortured by indecision. He can’t make a decision about a job, and of course, he can’t make a decision about a woman. He can’t decide on his political identity either; the onetime bridge builder sounds a lot more like a traditional minority politician. Medlar calls his hand on that too, after Cisneros tells her how he lobbied for Denver mayor Federico Peña to become Secretary of Transportation so that Clinton would have two Hispanics in the Cabinet.

She: [You] waved the flag around about being Hispanic all the time and you [say you] don’t want anything because you’re Hispanic, you know, but basically, you use it.

He: No. Well—

She: You know, when I knew you, that wasn’t the most important thing.

He: Well, it’s not.

She: I didn’t even think about there being a difference between you and I, but you wave it like a banner now.

He: It’s not true.

She: It is true. Look at the quotas—you and another Hispanic, you know how many blacks—it’s no longer, politics is no longer about the best person.

He: Yeah, it is.

She: No, it’s not.

He: Well, Linda, it’s time to give people a chance.

He has lost his way; he has been buffeted by life; he has let people down; he talks about saving his soul. Cisneros and Medlar quarrel about why he is going back into public service.

He: [HUD] is a very dumb move for me if it was about ambition. I’m going to come up scarred out of this thing, but I’m going to try. I mean, I wish you could see how bad things are across the country. I mean it’s like—I don’t know how to tell you, you make fun of me about everything I say that comes from the heart, but this is kind of like a duty I owe. I mean, it’s like amends. . . .

She: To be making amends on something—a lot of people can do it without having to be in the limelight or having to take public office, which you’ve always sworn that you would never do.

It is easy to see the appeal of HUD to Henry Cisneros. It is one thing in his complicated life that is clear and unambiguous. He no longer has the pressure of being a bridge; he is unmistakably the advocate for the poor. He is free to do good without worrying about what the business establishment wants, free to hand out money without worrying about raising taxes, free to advocate programs without having to face their consequences with the voters, free to serve without worrying about campaign contributions or federal judges or whether he belongs in the Anglo world or the Hispanic world. He can convince himself that of all the jobs in high government service, this one has the fewest rewards and is the least compatible with ambition. He has found the ultimate worst-case scenario: He is Secretary of Poverty.

I love this view!” Henry Cisneros said, as the USAir turboprop descended toward Washington. The panorama of the capital unfolded beyond the right wing: the monuments, the massive buildings, the avenues, the Capitol itself. We were returning from the graffiti-marred, rubble-strewn urban wasteland of North Philadelphia, and Cisneros was elated with the trip. It had begun awkwardly at Sister Fattah’s home for troubled boys, with Cisneros trying to find common ground with seven black teenagers and not getting much response from questions like “What are things like on the streets?” and “How many gangs are in the neighborhood?” The youths hadn’t even heard of San Antonio until Cisneros, desperately reaching for the nearest stereotype, blurted, “The Spurs! David Robinson!” But then he went to a midnight basketball game between youth gangs, and to a reception given by the tenants’ council at a public housing project and, after spending the night at the project, to a press conference at city hall, where he handed the mayor a check. He was so like the Henry Cisneros of old—energetic and enthusiastic and well intentioned—that he seemed to be everything a politician should be.

But he was one thing a politician should not be, and that is introspective. As a politician, it was not enough for him to do right; he demanded of himself that he do right for the right reason—and personal ambition wasn’t a right reason. His self-doubt drove him away from elected office and away from Texas. Now, somewhere down on the ground below the airplane, people were combing the transcripts for evidence of wrongdoing, and on the seat beside him, there was the New York Times with its headline about Mike Espy’s resignation.

Cisneros tapped the Espy story with his hand. “Did you see this?” he asked. “It means they’re going to be after me now.”

“Do you think you’re going to make it?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Cisneros said. “It’s not up to me.” He shrugged.

“Whatever happens, happens. I’m at peace.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Scandal

- Longreads

- San Antonio