William Rice Lummis began the morning of April 5, 1976, just as he had begun almost every other Monday morning for the last twenty years: he got up, put on a gray business suit, kissed his wife Fran, and drove his tan Volvo from their vine-covered brick home in River Oaks to the downtown Houston law offices of Andrews, Kurth, Campbell, and Jones, where he became immersed in the details of a firm management committee meeting.

But this close and comfortable routine was not destined to last much longer. Shortly after two o’clock that afternoon, Lummis learned that his first cousin Howard R. Hughes was dead at Methodist-Hospital. Moments later, Lummis found himself rushing out to the Texas Medical Center, already haunted by the realization that the course of his own well-protected life had just been irrevocably changed.

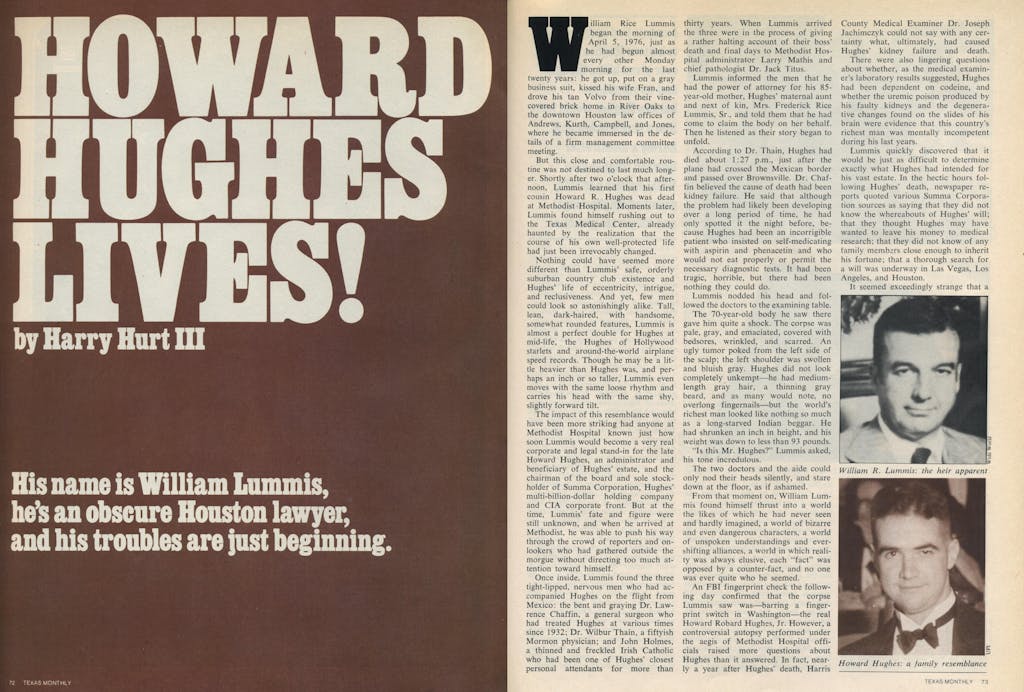

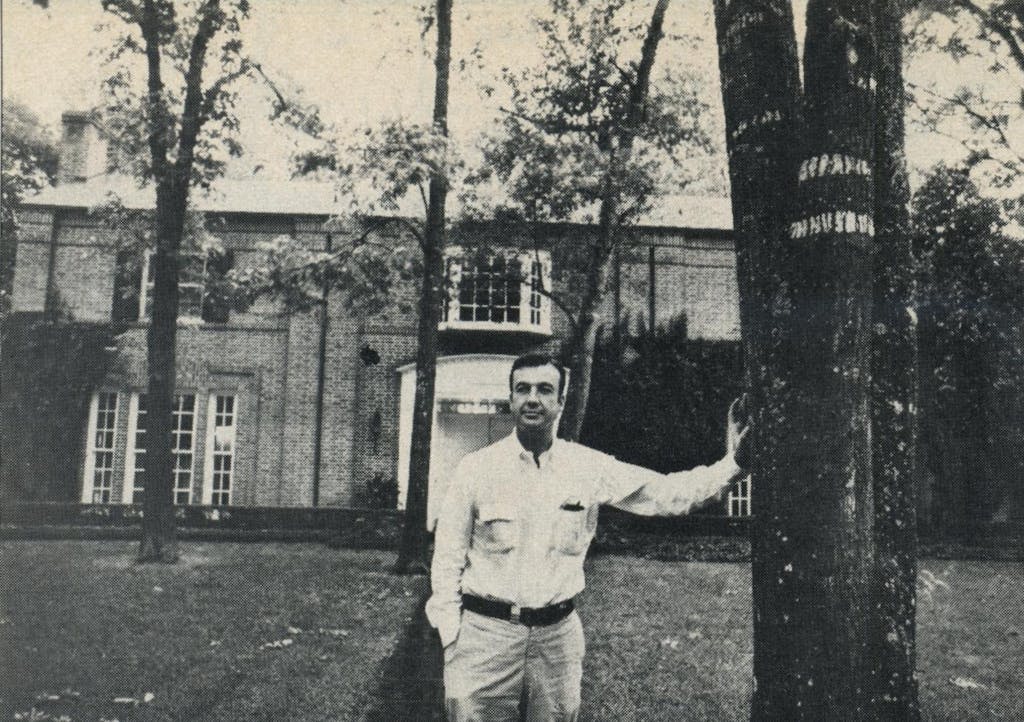

Nothing could have seemed more different than Lummis’ safe, orderly suburban country club existence and Hughes’ life of eccentricity, intrigue, and reclusiveness. And yet, few men could look so astonishingly alike. Tall, lean, dark-haired, with handsome, somewhat rounded features, Lummis is almost a perfect double for Hughes at mid-life, the Hughes of Hollywood starlets and around-the-world airplane speed records. Though he may be a little heavier than Hughes was, and perhaps an inch or so taller, Lummis even moves with the same loose rhythm and carries his head with the same shy, slightly forward tilt.

The impact of this resemblance would have been more striking had anyone at Methodist Hospital known just how soon Lummis would become a very real corporate and legal stand-in for the late Howard Hughes, an administrator and beneficiary of Hughes’ estate, and the chairman of the board and sole stockholder of Summa Corporation, Hughes’ multi-billion-dollar holding company and CIA corporate front. But at the time, Lummis’ fate and figure were still unknown, and when he arrived at Methodist, he was able to push his way through the crowd of reporters and onlookers who had gathered outside the morgue without directing too much attention toward himself.

Once inside, Lummis found the three tight-lipped, nervous men who had accompanied Hughes on the flight from Mexico: the bent and graying Dr. Lawrence Chaffin, a general surgeon who had treated Hughes at various times since 1932; Dr. Wilbur Thain, a fiftyish Mormon physician; and John Holmes, a thinned and freckled Irish Catholic who had been one of Hughes’ closest personal attendants for more than thirty years. When Lummis arrived the three were in the process of giving a rather halting account of their boss’ death and final days to Methodist Hospital administrator Larry Mathis and chief pathologist Dr. Jack Titus.

Lummis informed the men that he had the power of attorney for his 85-year-old mother, Hughes’ maternal aunt and next of kin, Mrs. Frederick Rice Lummis, Sr., and told them that he had come to claim the body on her behalf. Then he listened as their story began to unfold.

According to Dr. Thain, Hughes had died about 1:27 p.m., just after the plane had crossed the Mexican border and passed over Brownsville. Dr. Chaffin believed the cause of death had been kidney failure. He said that although the problem had likely been developing over a long period of time, he had only spotted it the night before, because Hughes had been an incorrigible patient who insisted on self-medicating with aspirin and phenacetin and who would not eat properly or permit the necessary diagnostic tests. It had been tragic, horrible, but there had been nothing they could do.

Lummis nodded his head and followed the doctors to the examining table.

The 70-year-old body he saw there gave him quite a shock. The corpse was pale, gray, and emaciated, covered with bedsores, wrinkled, and scarred. An ugly tumor poked from the left side of the scalp; the left shoulder was swollen and bluish gray. Hughes did not look completely unkempt—he had medium-length gray hair, a thinning gray beard, and as many would note, no overlong fingernails—but the world’s richest man looked like nothing so much as a long-starved Indian beggar. He had shrunken an inch in height, and his weight was down to less than 93 pounds.

“Is this Mr. Hughes?” Lummis asked, his tone incredulous.

The two doctors and the aide could only nod their heads silently, and stare down at the floor, as if ashamed.

From that moment on, William Lummis found himself thrust into a world the likes of which he had never seen and hardly imagined, a world of bizarre and even dangerous characters, a world of unspoken understandings and ever-shifting alliances, a world in which reality was always elusive, each “fact” was opposed by a counter-fact, and no one was ever quite who he seemed.

An FBI fingerprint check the following day confirmed that the corpse Lummis saw was—barring a fingerprint switch in Washington—the real Howard Robard Hughes, Jr. However, a controversial autopsy performed under the aegis of Methodist Hospital officials raised more questions about Hughes than it answered. In fact, nearly a year after Hughes’ death, Harris County Medical Examiner Dr. Joseph Jachimczyk could not say with any certainty what, ultimately, had caused Hughes’ kidney failure and death.

There were also lingering questions about whether, as the medical examiner’s laboratory results suggested, Hughes had been dependent on codeine, and whether the uremic poison produced by his faulty kidneys and the degenerative changes found on the slides of his brain were evidence that this country’s richest man was mentally incompetent during his last years.

Lummis quickly discovered that it would be just as difficult to determine exactly what Hughes had intended for his vast estate. In the hectic hours following Hughes’ death, newspaper reports quoted various Summa Corporation sources as saying that they did not know the whereabouts of Hughes’ will; that they thought Hughes may have wanted to leave his money to medical research; that they did not know of any family members close enough to inherit his fortune; that a thorough search for a will was underway in Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and Houston.

It seemed exceedingly strange that a man as meticulous as Hughes, a man surrounded by cadres of the country’s best lawyers, would have no clear will, and Lummis sincerely hoped and expected one would appear. But he also knew that if none was forthcoming, he and his family would indeed be in a position to inherit some and possibly all of Hughes’ fortune.

So did Chester C. Davis, the general counsel for Summa Corporation. A frenetic, balding, impenetrable man in his early sixties, Davis arrived in Houston the day after Hughes’ death to meet with Lummis and Milton H. (Mickey) West, the Andrews, Kurth lawyer who handled the firm’s work for Howard Hughes.

Davis got right to the point. Although he had always understood that Hughes intended to leave his estate to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Davis said he and the other old hands in the Hughes organization simply did not know where Hughes might have left a valid will in which these and/or other intentions were stated. In the meantime, the April 15 tax deadline was approaching, and Summa Corporation needed to have an owner. Davis wanted Lummis and his family to file for the posts of temporary co-administrators of Hughes’ estate in the various possible jurisdictions. If a valid will was found, they could step down. If no will was found, the estate would be the family’s responsibility, anyway. Whatever developed, Davis and Summa vice president F. W. (Bill) Gay, the longtime Mormon power in the corporation, would see that things continued to run smoothly from day to day.

Lummis was impressed with Davis at this first encounter. He seemed to have a way of explaining things quickly, simply, concisely—at least when he wanted to. Lummis did not know much about Gay and the other executives—he assumed, not altogether correctly, that they had probably never made a decision for themselves in their entire careers. But this loquacious, demonstrative Summa counsel seemed to have something on the ball. Lummis agreed that he and his family would cooperate as best they could.

On April 14, only one week after Hughes’ funeral, Lummis and his law partners at Andrews, Kurth began a series of legal moves designed to give him and his family administrative control over Hughes’ estate in Nevada and Texas, while Chester Davis’ law firm, Davis & Cox, represented Lummis’ cousin Richard Gano in filing for an ancillary administration in California. Three weeks later, Summa Corporation, with the legal counsel of Chester Davis, persuaded the chancery court in Delaware to appoint Lummis temporary sole stockholder of the company with the power to vote its stock. Thus, barely a month after Howard Hughes died, Will Lummis had fully assumed Hughes’ legal and corporate personae.

After this auspicious and well-coordinated beginning, Lummis’ relationship with Chester Davis would become severely strained—almost, Lummis’ attorneys would assert, to the breaking point. Amid the tides of fact and counter-fact, Lummis would be informed that Chester Davis had been running Summa instead of—and not necessarily in the interests of—Howard Hughes for many, many years. He would be told that Davis had more knowledge about a possibly valid will than he first let on; that Davis planned to “use” Lummis and his family to perpetuate his own power; and that as far as the affairs of Summa were concerned, when Chester Davis made up his mind to do something, it would be very hard to stop him.

But in the first few weeks after Hughes’ death, Lummis and Davis remained on amiable terms, and after joining wholeheartedly in the will search, Lummis’ main concern became unifying the various members of the family who were likely to inherit if no valid will was found.

The irony in this task was that Howard Hughes and his family had neither seen nor spoken to each other in years. In fact, Lummis himself had only seen Howard Hughes in the flesh twice—once in 1933, when Lummis was four years old, and then again in 1938, when Lummis was nine. Except for a wedding present and a 1933 letter in which Hughes had referred to young Will as “adorable,” Lummis had little reason to believe Hughes had ever given him and his own life a thought, and no reason to believe Hughes would leave him a single poker chip.

Hughes’ closest living relative was Will’s mother, Annette Gano Lummis. Tall, lean, and strong-boned, with a shock of gray curly hair, Annette Lummis was one of the few surviving matriarchs of a time and class of people now nostalgically referred to as “Old Houston.” She had gone to Wellesley College, class of 1911, and had married Dr. Frederick Rice Lummis, Sr., a cousin of the Rice University founder, who was a decorated World War I hero, a highly respected physician, and Rice University trustee. Though she was now frail and forced to walk with a brace, Mrs. Lummis was still lucid and sharp. She had a great deal of money, but she did not like to flaunt it, and she particularly did not like to talk about her rich and eccentric relations, especially not her nephew Howard.

Will Lummis would later testify that if anyone had raised Howard Hughes, “it was my mother,” but in fact she had only taken charge of Howard for a short time after his mother died, then again for about a year, starting in 1925, after Howard’s father died. Hughes also lived with another maternal aunt, Mrs. J. P. Houstoun, Sr. Still childless herself, Mrs. Lummis had moved into the Hughes family home on Yoakum Boulevard in 1925 to see what she could do for her nephew. But young Howard, then nineteen, was not about to have anyone tell him what to do. He persuaded the court to waive his disabilities as a minor, bought out his father’s relatives, and took full control of the stock of Hughes Tool Company. Then he informed his aunt he was going to fly to California to make movies.

Before Howard left, Mrs. Lummis acquiesced to a classic Old Houston society marriage between Howard and Ella Rice, a niece of both Rice University founder William Marsh Rice and Dr. Lummis, in hopes that she might provide the boy with some stability. But once in California, Howard took the attitude that his wife and all his other relatives could go to hell. Howard only rarely returned to Houston until the day he flew in dead. In 1929, Ella came back home and filed for divorce. In 1946, when Mrs. Lummis rushed to California to inquire about Howard’s condition after a near fatal airplane crash, he refused to see her; she went away hurt and blamed Hughes’ aide Noah Dietrich for poisoning Howard’s mind against them.

Contrary to popular belief, Howard’s relations with his relatives were not all bad. He sent Will Lummis and several of his other Houston first cousins some of their nicest wedding presents—silver bowls, silver trays, crystal, and such—and in 1971, on the occasion of his Aunt Annette’s eightieth birthday, wrote her a cherished two-page telegram in which he praised her beauty as a young girl, and her strength as a mature woman, and promised that despite his long absence from Houston, he would one day soon show up at her door. Though admirably intentioned, it was a promise he never kept.

The few times Hughes did come to Houston, he seemed to bring a great deal of excitement but also a considerable amount of trouble. This was especially true in 1938, the second of the only two times Will Lummis ever saw his famous first cousin. The occasion was a ceremonial parade honoring Hughes’ record-breaking around-the-world airplane flight. The event took place a few years after the Lindbergh kidnapping, and, although Willie and the other kids got to ride in the parade, they discovered that their mothers and fathers and aunts and uncles had been forced to hire bodyguards for them. The protection continued for a short time after the parade, and the children were cautioned about whom they spoke to and whom they came near. It was not a very enjoyable way to grow up, and undoubtedly reinforced the innate family shyness as well as the family’s ambivalence toward cousin Howard.

Consequently, it was with considerable trepidation that William Lummis called a family meeting at his sister Annette Neff’s house in River Oaks shortly after Howard died. At the time, Lummis’ knowledge of the living members of the family tree was limited to the maternal side—the Ganos, the Houstouns, and the other Lummises—so it was only the twelve first cousins, the closest surviving kin after his mother, that he invited to attend.

The oldest and the oddest of the first cousins was William K. Gano, 61, who, in a sort of blue-collar variation on Howard, had spent his days as an oilfield equipment worker and tool manufacturer. Retired because of a lung difficulty, he lived in a low-income northwest Houston neighborhood behind Cameron Iron Works and pursued a hobby of collecting junk. The rest of the cousins were between the ages of 59 and 45 and were either businessmen or professionals like Will and his brother, Dr. Frederick Rice Lummis, Jr., or housewives like his sister Ann. Richard C. Gano, the only relative to work for one of Howard’s companies, lived in California, and was a former employee of Hughes Aircraft. Will’s sister Allene was married to a physician in Boston, but the rest of the cousins all lived in Houston and, with dull regularity, raised families, played golf or tennis, and sent their children to good schools.

There were also some first cousins once removed: the children of the late William Gano Houstoun, Sr., aged 13 to 22, who were in line to inherit their father’s share, but they were all away at school or up in the mountains in Colorado.

None of these kinfolk had expected Howard Hughes to remember them in his will, and none of them really cared. In fact, they would have preferred that Howard had just left them alone. They had all gotten along just fine without Howard and his money, and they had planned to continue doing so in the future. Now they would be harassed by reporters, money seekers, and plain nuts. They and their children and their children’s children would probably have to live the rest of their lives under armed guard. And the ultimate irony was that the estate would probably be so tangled in litigation and so depleted by taxes that neither they nor the first two generations of their descendents would ever receive a penny from this dubious boon of their birthright.

The depth of this family mood became apparent early in the meeting, when Will’s brother, Dr. Fred Lummis, Jr., asked about the possibility of settling on one of the many purported wills that were surfacing in post offices, courthouses, and Mormon churches around the world: “Why can’t we just say that the one that gives the most to charity is the real will, and just let it go at that?”

Will’s answer was straight-arrow simple. “Because it would be against the law.” In addition to their moral responsibilities, the family was bound to the estate by certain technical-legal requirements. They could not simply throw their support behind a bogus will, no matter how worthy its beneficiaries might be. If Hughes’ death had fastened the family to his strange fortune, the law kept them chained to it.

On the other hand, it was not certain that all of them would be eligible to share in the estate. Who got what would depend on which state was determined to be Hughes’ legal residence. Under Nevada law, the entire estate would go to Will’s mother; the other cousins would get nothing. Under Texas law, the estate would be divided equally between the maternal and paternal sides. Will wanted to fashion some sort of agreement that allowed them all to take at least some share of the estate if no will was found. It would be almost like a speculative investment. Though the tax bite might be great, skillful lawyering could still save hundreds of millions for them. The payoff might not come until far in the future, but the estate could still turn out to be quite a windfall.

As far as the family was concerned, whatever William wanted to do was fine. They would give him whatever support they could, but frankly, they would just as soon leave the whole thing to him and the lawyers at Andrews, Kurth. They would prefer to make no comments, know nothing, not get involved in the nitty-gritty of it. They all agreed Will should be the spokesman. And the lightning rod.

The meeting broke up in a stir of apprehensiveness, and Will Lummis began to think about the unlikely new challenge which lay before him: the inheritance of Hughes’ vast and multifarious empire.

Though hardly the eccentric genius his cousin Howard had been, Lummis was not altogether ill-equipped. Among his principal assets was his association with the law firm of Andrews, Kurth, one of the oldest, most socially connected, and most conservative of the big Houston firms. Andrews, Kurth had handled legal work for Hughes, Hughes Tool Company, and later Summa Corporation, for over half a century. Though the firm would later claim it had ceased to be the primary legal representative for Hughes in 1969, it still handled substantial tax work and other matters for Hughes and Summa. In fact, the address often used by Howard Hughes as his own—the address which appeared on his tax returns and on his death certificate—was the twenty-fifth floor of the Exxon Building in Houston, the office address of Andrews, Kurth.

While Lummis himself had no real experience with Hughes’ affairs, he could look for help from Milton H. (Mickey) West, a bespectacled tax lawyer who had been the dominant influence in the firm for two decades. Behind West was an armada of legal talent which included names like Hall A. Timanus, longtime leader of Texas’ George Wallace forces; James A. Baker III, national director for President Ford’s campaign; and Jim Dilworth, the gritty trial lawyer who would represent Lummis and family in the Hughes case. In all they were a very competent—as well as smug and self-confident—group.

Lummis’ own connection to the firm came both through cousin Howard and through marriage. Following in the family tradition, he attended Episcopal High School in Alexandria, Virginia, then did two years of pre-med study at Rice, only to become frustrated with the idea of becoming a doctor. He transferred to the University of Texas, where he joined the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity and married a dark-haired girl named Frances Bradley, the daughter of Palmer Bradley, one of the most prominent senior partners in Andrews, Kurth, a founder of the Dixiecrat party, and the scion of a family one friend described as “the living end of the Old South.” By the fall of 1953, Will had his law degree and was on his way to Andrews, Kurth, where his new father-in-law so happened to handle the account of his first cousin, Howard Hughes.

Lummis had never displayed the leadership qualities of a John Connally or a Leon Jaworski, but he was not merely dead weight carried along on the strength of his family connections. “He was just a competent, hard-working lawyer who did his job and did not make a lot of noise about it,” a former associate recalled recently. “He went through all the same things the other young associates went through, and never put on airs or appeared to be overly impressed with himself. I’m sure that at least some of the newer members of the firm didn’t even know he was related to Howard Hughes.”

Like his cousin Howard, Lummis preferred to keep his business close and private; unlike Howard, he also preferred to keep them conventional and family-oriented. One of his principal business investments was the Southern National Bank in Houston, which he founded in 1960, at the age of 31, in partnership with his father-in-law Palmer Bradley, his late cousin J. P. (Pat) Houstoun, and a cousin-in-law, John H. Lindsey. Thanks to help from Texas Eastern, which bought into the bank in the mid-sixties, and Texas American Bancshares (TAB), which absorbed it into its holding company structure in the early seventies, Southern National grew from an initial capitalization of $2 million to over $200 million in deposits by 1976, making it Houston’s eighth-largest bank. Though Lummis was by no means the sole driving force behind the bank’s growth, he did serve as an influential director and general counsel. He sits on the board of directors of both Southern National and Texas American Bancshares, and holds over 25,000 shares of TAB stock, which is worth approximately $500,000 at recent market prices.

His friends say that Will has a dry wit and is not always the reserved character he seems—he likes to tip a few and is known to sing a mean version of “Alouette” in French—but for the most part, he goes out of his way to keep a low and very proper profile. “Willie is the kind of guy who has a very strong sense of the private and the personal,” observed a good friend. “He’s a product of the old school.” In fact, before Hughes died, many of Lummis’ neighbors did not even know how to pronounce his name (it’s “Luh-mis,” not “Loo-mis”).

Having grown up in the Yoakum Boulevard house Howard Hughes deeded to his mother in 1926, Will built his own house on Inverness Lane, an area best described as “upper River Oaks.” On the weekends, he would go down to the Texas Corinthian Yacht Club and sail with friends and former schoolmates like George Francisco and Ford Hubbard, play a few sets of tennis, or hunt ducks out at the Eagle Lake Rod and Gun Club, one of Texas’ most acceptable places to fall in the water. Later, he sold his bay house and took up golf. He was a member of the best and most exclusive of the country and social clubs—the Bayou Club, Houston Country Club, the Tejas Club, Allergo—and though not a political partisan, he dutifully contributed to the most conservative candidates, which in 1976 included both Reagan and Ford. His taste in clothes ran toward Brooks Brothers. “One of Willie’s hobbies is loving his wife,” said a friend, “which is pretty significant given old Howard’s track record.” They have four sons, aged 15 to 23.

Close friends and classmates used to tease Will about his famous cousin from time to time, but he generally took it good-naturedly, and even joined in the fun. One old friend recalled, “We used to play Monopoly and call it Howard Hughes. Willie thought it was hilarious.”

It did not take long, however, for Will Lummis to realize he was playing the game of Howard Hughes for real. Shortly after meeting with Summa counsel Chester Davis, Lummis and Mickey West flew to Los Angeles, where they met with Hughes’ private physicians and closest personal aides in a private dining room in the Century Plaza Hotel. The purpose of the meeting was to find out what these men might know about Hughes’ will and his intentions regarding his legal domicile. Lummis had hoped that by interviewing them collectively, he would prompt them to stimulate each other’s memories.

As it turned out, the meeting developed into something of a low comic disaster, with Lummis, the look-alike cousin and heir apparent, asking broad, polite questions, and the tight-lipped old doctors and blue-suited Mormon aides giving stammering, incomplete answers and glancing at each other around the room, trying—without revealing too much—to feel out this newcomer upon whom their livelihood suddenly seemed to depend.

Whether or not Lummis finally gained a little of their confidence, the doctors and the aides did not give him any good leads on the whereabouts of a valid will. Neither did subsequent questioning, file searching, and interviewing. In fact, for all his work, Lummis uncovered only three potential trails in the halls of the Hughes organization—a will Frank Andrews of Andrews, Kurth had worked on in 1925; a will Hughes himself had worked on in the forties; and a will Hughes aide Noah Dietrich and Hughes’ secretary Nadine Henley had worked on in the fifties. Lummis could not find the first two of these wills. The third he found to be unexecuted and unfinished. Lummis’ discovery with respect to Hughes’ legal residence was somewhat more fruitful. As he later reported under oath, the meeting with the doctors and the aides at the Century Plaza convinced him “overwhelmingly” that Hughes intended to return to Nevada “as soon as he could have some assurance that he wouldn’t have to spend the rest of his life on the witness stand in various litigations.”

As Lummis turned from his will search to his role as administrator of Hughes’ estate and inheritor of his corporate legacy, he quickly learned what his first cousin had meant about spending time in court. Although Lummis was having problems finding a will, several other people seemed to be doing quite well at it, and in the last days of April, the first of more than thirty Hughes wills began to turn up. Some bequeathed Hughes’ fortune to a list of Social Security numbers; others to long lost friends and alleged illegitimate children. But only two were offered for probate.

The strongest alleged will is the “Mormon will,” which turned up in Mormon headquarters in Salt Lake City on April 29, about three weeks after Hughes died. Dated March 19, 1968, and written on lined yellow note paper, the document names former Hughes aide Noah Dietrich executor of estates and bequeaths money to Melvin Dummar, a gas station attendant who claims to have once given Hughes a lift in the desert; Rice University; the University of Texas; the University of Nevada; “orphan children”; “the key men” in Hughes’ companies; and others. Lummis, whose name is spelled “Loomis” in the will, is cut in, but only for one-sixteenth of the estate.

Noah Dietrich hired flamboyant Los Angeles lawyer Harold Rhoden, Houston attorneys George J. Parnham and Jack E. Withem, and a crew of other lawyers to represent the alleged will, and they soon saw that Lummis had his day in court. Carefully taking the law to its limit, Rhoden subpoenaed him, put him on the stand, and grilled him about everything from the way he pronounced his name to the claims, legal and administrative, he had approved against the estate. Lummis was made to wait outside the courtroom all morning because his case did not come up until the end of the docket and, on top of it all, had to suffer the humiliation of listening to Rhoden wrongfully accuse him of lying to Houston Probate Judge Pat Gregory about the amount of a filing fee paid to the court in Delaware.

But if contesting the Mormon will proved painful, Lummis found himself fighting his fiercest battle against Texas Attorney General John Hill, who is attempting to claim $300 million in inheritance taxes for the state if he can show that Hughes was a legal resident of Texas when he died.

All of Lummis’ motivations for this battle are not clear: contrary to some reports, the estate will have to pay taxes if Hughes’ legal residence is proved to be Nevada. But there is no doubt that Lummis has received a rude education in the interaction between public watchdogs and great private wealth. For example, one afternoon after giving his sworn statement in the offices of Andrews, Kurth, Lummis heard the formerly obliging Hill accuse him of changing from a neutral position on domicile to one favoring Nevada. “You’re cheaters,” Hill stormed. “You’re trying to cheat the State of Texas, and you ought to be ashamed of yourselves.” Lummis and two of his attorneys sat there agog.

Meanwhile, Will Lummis and his lawyers soon discovered some more heirship problems to resolve. In early May, about a month after Hughes died, Lummis learned of three female first cousins on the paternal side of Hughes’ family: Agnes Lapp Roberts and Elspeth Lapp De Pould of Cleveland, and Barbara Cameron of Los Angeles. They are the granddaughters of Rupert Hughes, Howard’s uncle. All three are housewives and absolutely unknown to Will Lummis and the other members of the maternal side of the clan. Embarrassed for having overlooked “the Hughes girls,” as he called them, Lummis rushed to Los Angeles to apologize and meet with their attorney Paul Freese.

If the will is probated in Texas, the Hughes girls stand to inherit half the estate. In Nevada, they would get nothing. A costly internecine battle between the maternal and paternal heirs could be in the offing if they did not ally or else agree on Texas instead of Nevada. Already attorney Freese has said in a paper filed in probate court in Las Vegas that his clients’ preliminary review of the facts suggested a Texas domicile.

With another remarkable display of legal alacrity, Lummis and his lawyers came up with a sixteen-page Settlement Agreement. No doubt because of this strong contention that Hughes was a legal resident of Nevada—in which case Mrs. Lummis, Sr., would be entitled to the entire estate—the Lummises got the best of the deal. In essence, it said that if no will was found, the maternal heirs would receive 75 per cent of the estate in the following subportions: 25 per cent for Mrs. Lummis, Sr.; 16(2/3) per cent for Will and his two sisters and brother; 16(2/3) per cent to be divided among the ten members of the Houstoun family; and 16(2/3) per cent to be divided among five members of the Gano family. The remaining 25 per cent would be divided among the paternal heirs, regardless of where the estate was probated. In addition, Mrs. Lummis, Sr., retained the option of giving 25 per cent of the estate to any charitable organization asserting a claim against the estate before any division was made. The Lummises, meanwhile, were made the de facto leaders of the agreement. Though signed in early July, the agreement remained a closely held secret until mid-August, and was not filed in court until August 27. Shortly afterward, the Hughes girls began to say that they had been mistaken and misinformed to think Texas was Hughes’ domicile, that his actual domicile was Nevada. Word got out that Mrs. Lummis, Sr., had inspired the agreement because she did not want to endure the spectacle of the family fighting in public.

Hardly had the ink on the agreement dried, however, than more heirship problems arose on the paternal side. In August Avis Hughes MacIntyre, a 74-year-old gentlewoman who lives outside Montgomery, Alabama, and Rush Hughes, a 76-year-old former movie producer and radio star, filed a claim asserting that they were the “equitably” adopted heirs of Howard’s uncle, Rupert Hughes. Though still considered something of a longshot, the potential impact of the claim is staggering, for if the two are successful, they could inherit as much as one-third of Hughes’ estate. Avis MacIntyre and Rush Hughes also joined Attorney General Hill and the Houston court-appointed ad litem attorney in claiming Hughes was a legal resident of Texas.

But even as he fought these court battles, Lummis also had to worry about administering the estate and running Summa Corporation. Given the “alter ego” relationship Hughes had to his corporate personality, the two jobs were very nearly indivisible, and, as Lummis soon learned, fraught with conflict. Early on, he had observed that “there are a lot of faucets going, and there’s going to have to be some spigot turning.” Some of the spigots—like the $90,000 hotel bill the Hughes party ran up in Acapulco—were shut off automatically by Hughes’ death. Others required more aggressive turns. In the first six months of their tenures as administrators, Lummis and his cousin, Richard Gano, sold one airplane and cancelled the leases on three others. They sold Hughes’ house on Rim Road in Palm Springs, California, and dismissed the servants with severance pay. They also advertised the sale of the rights to The Outlaw, Jet Pilot, and The Conquerors. The total estimated net value to the estate from these transactions was a little less than $3 million.

But during this same period, Lummis also approved claims against the estate for a total exceeding $42 million. The most controversial claim was a $393, 945.08 bill from Andrews, Kurth for services to the estate by 26 lawyers between April 5 and August 31, 1976.

Among other things, the bill rather graphically illustrated the sort of chunk at least some of the lawyers would be taking out of the estate. And this was just for the first five months work.

The bill also gave a fair indication of the many roles, interconnections, and, according to some, possible conflicts of interest Will Lummis has in the Hughes case: it was addressed to him as temporary co-administrator and asked for him to approve payment for services he himself had rendered to the estate before taking an indefinite leave of absence from the firm on May 15. After Lummis did approve the bill, Attorney General Hill filed a challenge with the allegation that Lummis and his attorneys had spent their time not in the impartial interests of the estate but in preparing a partisan case favoring Nevada domicile.

As these and other sticky questions remained unanswered, Lummis went on to approve by far the largest claim against the estate—$41 million in bank loans to Hughes from Texas Commerce Bank, First City National Bank, and Bank of the Southwest, a filing which gave a pretty good idea of the real depth of Howard Hughes’ involvement with the core of the Houston business establishment and their involvement with him. It later developed that the loans were originally made in 1971 to cover indebtedness incurred in connection with the purchase of the Sands. Since Hughes had done business with Texas Commerce Bank and its corporate predecessors for over forty years and was currently the bank’s largest single depositor with an estimated $60 million in certificates of deposit, he had not been required either to appear at the banks or to offer proof of his general health or the provisions of his estate—a courtesy which would later come back to haunt.

In the meantime, however, Lummis had to concern himself with the task of overseeing the operations of Summa Corporation and its 15,000 paid employees. As one friend observed, it was as if Lummis had suddenly been promoted from captain of the mess to general of all the armies. He found that the properties he owned with his Summa stock included seven gambling casinos (the Sands, Desert Inn, Frontier, Silver Slipper, Castaways, and Landmark in Las Vegas, and Harold’s Club in Reno); a television network; Hughes Air West airlines; a helicopter plant; some 1200 mining claims; as much as 100,000 acres of developed and undeveloped prime acreage in California and Nevada; and an ocean mining division whose chief claim to fame was its role as a front for the fabled CIA spy ship, Glomar Explorer.

Months after becoming sole stockholder of Summa, Lummis still had no reliable idea of what all this empire might be worth. The working figure in the press is $2.5 billion, but estimates range from almost twice that amount to less than $500 million. In his capacity as estate administrator, Lummis hired Merrill Lynch to do an appraisal of Hughes’ holdings and expects their report in early 1977, but even then it will be hard to get a true assessment of the net worth of Hughes’ holdings, since there are over sixty lawsuits pending against Hughes and/or Summa, with individual claims up to $200 million, and total claims much higher.

Compounding valuation problems even further is the matter of the CIA, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and $1.6-billion, 45,000-employee Hughes Aircraft (HAC), the nation’s eighth-largest overall defense contractor and largest CIA defense contractor. According to a groundbreaking series in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Hughes’ companies have taken in over $6 billion in public CIA contracts and $6 billion more in private CIA contracts in the last ten years. Hughes Aircraft, which specializes in electronics, is not part of Summa Corporation’s assets, but is owned by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, a tax-exempt foundation Hughes set up in 1953 with himself as sole trustee. Sooner or later, Lummis may have to decide what to do about the vacant trusteeship, as well as how to appraise and account for the other national security assets and how to handle future Summa-CIA involvement—if, that is, he has any choice in the matter.

As Nevada’s largest single private employer (over 8000 people), Lummis must also deal with the gambling state’s toughest and most notorious economic power, the Mafia. In the past, the relationship between Summa and the Mob has, as one might expect, been rather shadowy. In 1967, Hughes made his entrance into Las Vegas by buying the Desert Inn from former Cleveland hood Moe Dalitz. But even before then, the Hughes organization had established ties to the Mob through former Hughes aide Robert Maheu, who hired John Roselli and Sam Giancana for a CIA attempt to assassinate Cuban premier Fidel Castro. After the stormy Maheu period ended in 1970, the Hughes organization gained a reputation for making the casinos honest—that is, stopping the illegal cash rake-off or “skim” commonly practiced in local gaming establishments—but skeptics wondered whether Hughes had simply begun skimming for the CIA as well as for the Mob and for himself. The legalization of gambling in New Jersey will undoubtedly turn some of the gangsters’ attention toward the East Coast, but that can only mean the relative devaluation of Summa’s Las Vegas properties if Lummis does not choose to expand in the same area, and a vicious battle over the new turf if he does.

For the time being, however, Lummis’ biggest problems are not with the Mafia, the CIA, or the casino business, but with the “people problems” of the Hughes organization itself. One of the things Lummis must eventually decide is what to do about “The Boys,” the all-male crew of personal aides who attended Hughes constantly for nearly thirty years. Two of the aides, John Holmes and Levar Myler, were recently reelected to their positions as directors of Summa Corporation; as the highest-paid former members of Hughes’ personal staff, they still receive salaries in excess of $75,000 a year, but it is not clear what they and the others can or will be able to do to earn their paychecks now that Hughes is dead.

Much more pressing is the issue of what to do about Chester Davis and Bill Gay and the de facto control of Summa. Formally, of course, Will Lummis is the top man in the organization and its sole owner. On August 4, he was elected chairman of the board, and his law partner and friend Mickey West was made one of the thirteen directors. But since neither Hughes nor anyone else ever occupied the chairman’s position before, Lummis’ power and duties remain unspecified, and he and West remain outnumbered on the board by the organization’s old hands. Bill Gay has moved up from executive vice president to president and chief executive officer, while Chester Davis retains his influential position as general counsel and director. This arrangement began happily enough, but in recent weeks, the once coordinated Lummis-Summa front has showed several signs of what Lummis’ attorneys claim is a profound internal schism along classic “good guy-bad guy” lines.

In order to understand the situation fully, it is necessary to review some Hughes organization history and personnel background. Davis’ and Gay’s rise to the top leadership roles within the Hughes organization came in the controversial December 1970 ouster of former aide Robert Maheu. This was the occasion on which Hughes was spirited out of the Desert Inn when a strike force from a security agency called Intertel swept down on Maheu’s office and impounded the files. As proof of their authority, Davis and Gay later produced the famous “Dear Chester and Bill” letter, three pages of lined yellow note paper in which Hughes asked them to “take care of” the Maheu matter at once.

Of the two, Bill Gay had the most experience with Hughes. A wiry man with a gray crew-cut who holds a PhD in philosophy from UCLA, Gay is also the top Mormon power in the organization and the executive responsible for firing Hughes’ personal attendants. He began with Hughes over 25 years ago, helped set up the operations center at 7000 Romaine Avenue in North Hollywood, then became head of West Coast operations for Hughes Tool Company, the corporate predecessor of Summa Corporation. Gay is the brother-in-law of Dr. Wilbur Thain, one of the two physicians with Hughes on the plane to Houston. Dr. Homer C. Clark, another doctor who treated Hughes during his final days, is the brother of Gay’s executive assistant, Randy Clark.

A Houston banker who has done business with Gay describes him as “an inspirational man, very intelligent, with excellent personal habits,” and adds, “he looks like a jogger.” However, according to Playboy magazine, two memos from Hughes circulated by former Hughes aides Robert Maheu and John Meier are hardly so complimentary. In one, Hughes blames Gay for the break-up of his marriage to Jean Peters. In the other, Hughes writes that his “bill of complaints against Bill’s conduct goes back a long way and cuts very deep. Also, it includes a very substantial amount of money, enough to take care of any needs of his children many times over.” John Meier has charged that the money Hughes was referring to was from Hughes Dynamics, a corporation Gay allegedly set up without Hughes’ knowledge.

Whatever the case, Gay seems a picture of Mormon rectitude next to Chester Davis. Lawyers both for and against Davis in the Hughes case describe him as the roughest, toughest, meanest, and, in turn, most affable and engaging character they’ve ever run across. While representing all the Hughes organization witnesses in the Senate Watergate hearings about the $100,000 in cash Hughes gave to Nixon confidant Charles G. (Bebe) Rebozo, Davis once told his own client, Hughes aide Richard Danner, “You open that mouth again and you’re gonna have to see a dentist.” Davis’ status among the parties to the Hughes case is almost mythic and grows with the addition of each new biographical fact. For example, his real name is not Chester Davis, but César Simon. He was born in Rome, Italy, and he is believed to be of Italian, Jewish, and Algerian descent. He came to this country as a small boy, then attended Princeton and Harvard Law School. In 1961, Davis was in the trial section of a New York law firm when the Hughes half of the Howard Hughes-TWA litigation landed in his lap. He formed the firm of Davis & Cox, with one client, Howard Hughes, and has fought the same TWA litigation ever since. He has also represented Hughes with great skill and stamina in a wide range of other litigations, though he is himself both a civil and criminal defendant in the Air West Airlines stock fraud suit.

As William Lummis quickly learned, Davis is much more to the Hughes organization than his official positions as counsel and director might imply. He is the sort of man who seems to be everywhere and know everything—including the contents of the Hughes organization’s many dark closets. It seems only fitting that as the Hughes organization’s involvement in the Watergate affair was revealed to be much deeper than first suspected, it should turn out that Davis’ law partner Maxwell Cox is the brother of former Watergate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox.

Early on, the legal strategy by Lummis and Summa in the estate probate case bore an unmistakable resemblance to the hard-nosed tactics Chester Davis has used in the TWA litigation. Attorneys for the family spent five months resisting the inevitable disclosure of the Hughes autopsy report. They challenged the jurisdiction of the State of Texas in the Delaware, Nevada, and California courts, then challenged the standing of the Texas attorney general in the Houston court and took issue with all motions to produce documents.

But indications that all was not well within the empire began to surface in August, just after Lummis’ ascension to the post of chairman of the board, when Assistant Attorney General Rick Harrison asked Lummis to produce logs of Hughes’ stay in Mexico just prior to his death. Lummis’ attorney claimed Summa officials told him that the logs no longer existed because they were routinely destroyed. Harrison then revealed he had seen copies of the logs in Acapulco.

The next indication of an internal rift in the Summa-Lummis legal ranks came in early October, when, on the advice of a member of Chester Davis’ law firm, longtime Hughes personal attendant John Holmes failed to appear for his deposition in Los Angeles, later citing obscure technical reasons. Jim Dilworth, noticeably disturbed by the whole affair, got on the record as being in no way part or party to Holmes’ failure to show. In subsequent weeks, three other Hughes doctors and personal attendants also failed to appear for their depositions, again citing obscure technical reasons. When Holmes and another attendant, Roy Crawford, finally did give their depositions, their testimony conflicted on a number of key points, including their descriptions of Hughes appearance, their description of Hughes’ Desert Inn penthouse, and their statements about whether or not they kept logs of Hughes’ activities (Crawford said they did, Holmes said they did not).

But the most disturbing admission from Lummis’ point of view came in the legal jousting over the State of Texas’ request that he produce certain of Hughes’ personal and corporate documents relevant to the estate case. Lummis was forced to reply through his attorney that although he was chairman of the board and sole stockholder of Summa and would like to comply, he could not because he did not have actual control over the records. He said that Bill Gay was the company’s chief executive officer, and the man in control of the records. Lummis was admitting for the first time that he was in charge but not in command.

Attorneys for other parties to the suit retorted that if Lummis was unable to execute his duties as a temporary co-administrator, perhaps the court should find someone who could. They also asked why Lummis did not simply fire Davis or Gay or both if they did not produce records and comply with his legal wishes.

The unspoken answer, of course, was that Davis and Gay were too critical to the operation, knew too much about it. Lummis could not dismiss either one and expect them to leave without a fight. In fact, as well as being officers and directors of Summa Corporation, Davis and Gay controlled the board of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which owns HAC, and since Hughes’ death had asserted their intention to play major leadership roles. What is more, both men had a number of talented contributions to make to Summa’s progress.

And yet, an objective observer also had to ask if this ballyhooed Lummis-Summa schism was itself just a convenient legal subterfuge designed to avoid disclosure.

Then, just as Davis and Gay seemed to be consolidating their power, former Hughes aide John Meier began releasing a series of documents which threatened to turn the Hughes estate case upside down. Having served as an environmental expert, data processor, and special projects investigator for Hughes, Meier was the liaison between Hughes, former President Richard Nixon’s brother Donald, and Bebe Rebozo. It has largely been information provided by Meier which has led to the persistent theory that at least one motive for the Watergate break-in on June 17, 1972, was to determine how much Democratic party chairman Larry O’Brien, himself a former public relations man for the Hughes organization in Washington, knew about the $100,000 in cash Hughes gave to Rebozo.

Meier definitely bears a grudge against Summa. Because of an IRS indictment for back taxes allegedly owed on profits from some mining deals he made for Summa, Meier is a fugitive living in Canada on landed immigrant status granted by the Canadian government while he attempts to clear his name. He is also embroiled in a lawsuit Summa brought against him in Salt Lake City, for allegedly defrauding the company of its share in the mining deals. Nevertheless, his statements with respect to the Watergate case have so far proved remarkably accurate.

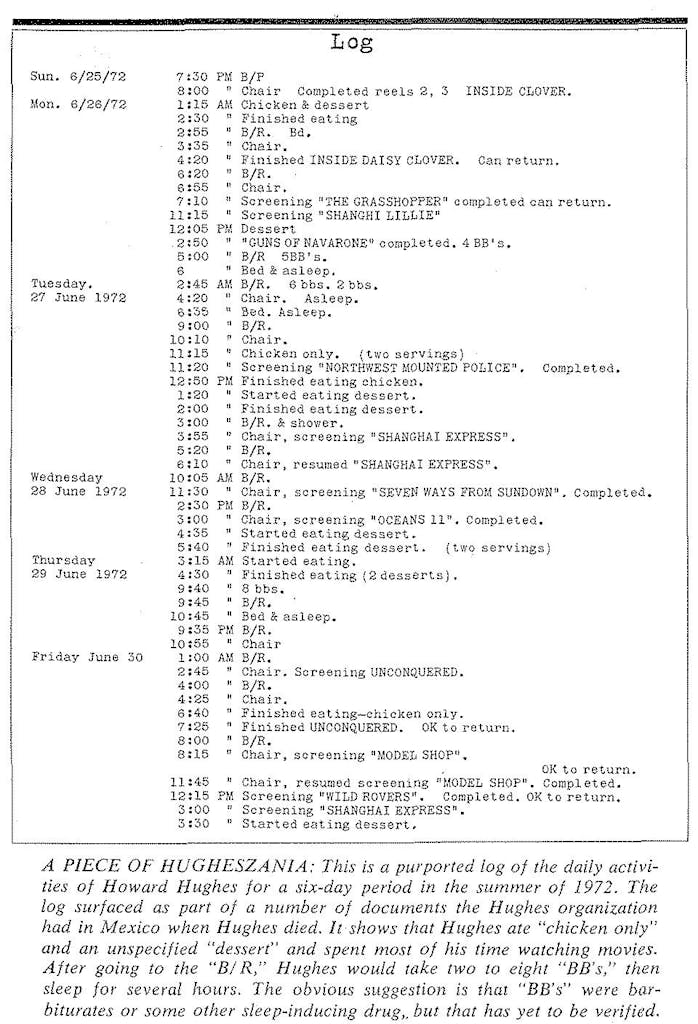

If the same holds for Meier’s statements about the Hughes estate case and the internal affairs of Summa, Chester Davis and several others in the Hughes organization could be in serious trouble. Meier began his bombshelling in early November when his attorney, Robert Wyshak, filed a series of memos and other documents in the Salt Lake City court. According to Meier, the documents are part of the Hughes organization files seized by Mexican authorities shortly after Hughes left Acapulco last spring. Among other things, Meier and his attorney say the papers indicate that Hughes aide Levar Myler forged or helped forge Hughes’ signature on a 1973 agreement to appear in court. Another Hughes memo asked that pressure on Meier and Las Vegas Sun publisher Hank Greenspun be dropped. Still another paper showed a daily activity log for Hughes for a six-day period in 1972.

Contacted by telephone, Meier was reluctant to reveal the contents of other documents he said he knows to be in the Acapulco files, but he did say the files “refer to a will” and that they contain more evidence of improper acts on the part of Hughes’ aides and associates. One example he has offered of possible improprieties is a purported memo from Hughes aide John Holmes in which Holmes admits signing Hughes’ name to some June 1975 renewals of the loans Hughes made from Texas Commerce Bank, First City National Bank, and Bank of the Southwest, because Hughes himself had “not been well enough.” Meier’s attorney has filed copies of the notes in the Utah court as well as the Holmes memo and a memo from Summa treasurer William Rankin to Hughes’ secretary Nadine Henley, in which Rankin explains that the debts had been incurred in connection with the purchase of the Sands and says that Hughes’ tax lawyers (among them Mickey West of Andrews, Kurth) advised extending at least part of the note into 1976, so that Hughes could take advantage of either the 1975 or the 1976 tax period.

While acknowledging that Meier does have at least some of the real Acapulco papers, Summa has denied the authenticity of the Holmes memo and the other incriminating documents. Summa cannot, however maintain that forgery is beyond anyone in the Hughes organization: last spring, Mexican authorities announced that Hughes aide Clarence Waldron admitted Hughes did not sign the tourist card he used to get into Mexico in February 1976; Waldron would not say who in their party did affix Hughes’ signature to the document. If the Meier version of Hughes’ Acapulco papers is authentic (and given the past history of the Hughes affair, they may or may not be), they could have about $41 million worth of implications for Houston’s largest and most prestigious banks. Even more, they could call into question every act—every transaction, every signature—Hughes executed in the last twenty years and provide new fuel for the theory that Hughes was mentally and physically incompetent during many of his waning years.

This in turn raises a host of consequent questions: If Hughes was not in control, who was? Davis? Gay? A cabal of aides? Is Lummis just a figurehead even now? Does Chester Davis have a secret plan to take over the Hughes empire? Is the family being used? Or is Chester Davis in reality a ruthless defender of the good—a guardian of the national security, perhaps—whose intentions and integrity have been unjustly impugned?

Only time will tell, but there are indications the plot will thicken further. In late November, authoritative Summa sources let it leak that the next explosive development in the Hughes case would be the surfacing of a “lost” will which leaves Hughes’ fortune to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. That would in effect leave control of the estate to Chester Davis and Bill Gay, the two men who control the board of HHMI.

In the meantime, William Lummis and his wife have moved to Las Vegas and taken up residence in the Sands Hotel, where they live in luxuriant discomfort amid throngs of gamblers, hustlers, tourists, and prostitutes. It was a move necessitated by the demands of running Summa Corporation, but one Lummis and his wife wish they could have avoided. “They don’t know anybody in Las Vegas, they didn’t want to live there, and I don’t think they’ve made too many friends since they’ve been out there,” a close friend has said. “You just can’t imagine Fran in a place like that. She’s so straight and proper, so completely opposite everything it stands for. I understand she’s spent most of her time holed up in the hotel.” Their sons have been out to visit several times, but the three youngest are away at school and the oldest is in law school and about to be married.

Much of the rest of the time, Fran and Will Lummis are on airplanes shuttling back and forth between Las Vegas and Houston. They have not sold their Houston home, but they are planning to build a new one in Las Vegas as soon as they can. Even there, they have found problems, for in the Las Vegas housing market, construction time and quality are nowhere near the standards that prevail in Houston. They and their four sons now travel with bodyguards. They have little time to socialize with friends. And, although Will enjoys an undisclosed six-figure salary, their world seems smaller. In short, the principal effect of becoming heirs to Howard Hughes has been to exchange their former lives of comfort and freedom for lives of anxiety and distress.

And yet, gradually but inevitably, Will Lummis seems to be becoming more and more like Howard Hughes. He makes no public comment except when legal proceedings require it, he grants no interviews to the media, he makes as few public appearances as possible. Although he tells friends he would be doing something else if he had his choice, he also says he rather enjoys the business aspects of his new life, the great challenge it represents, the salvation from middle-aged monotony.

It is certain that there will be no lack of challenges for Lummis in the future. Immediately over the horizon are a plenary hearing on the validity of John Meier’s version of the Acapulco papers, a trial on the Mormon will set for January 10 in Las Vegas, and a pretrial hearing on January 17 in Judge Pat Gregory’s Probate Court in Houston. But these are just more opening rounds in a legal battle which most participants expect will take many years, perhaps several decades, and which will most likely find its way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

What occupies William Lummis’ mind most heavily are the larger, more dangerous questions of the future. Each morning, he now begins his day by getting up, getting dressed, kissing his wife Fran, and taking a private car (one of the Hughes organization’s fleet of tan Chevrolets) from their suite at the Sands, down the Strip, and out into the barren suburbs, where a rather ordinary three-story glass-and-steel building—Summa Corporation’s official headquarters—sits amid an expanse of undeveloped land. Once inside the building, Lummis takes the elevator to the executive level, which at Summa happens to be two floors underground. He passes the receptionists and the maze of Mission: Impossible-style electronic security checks, and turns down a long hall toward his office, where he often sits and wonders how to gain control of the byzantine affairs of Howard Hughes, how to separate fact from fiction, mere appearance from reality, and, in darker moods, whether he will be around long enough to find out.