This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

There I was, sitting forlornly at the kitchen table, staring at a massive pile of bills, crying a little, cursing a little, and realizing that at last the time had come. I had to get a real job. There was no getting around it. I’d already sold everything that wasn’t nailed down—except the stereo my teenage daughter refused to relinquish—in order to continue writing, and I was getting nowhere.

Then, as if God were speaking to me personally, the answer to my problems appeared in a television commercial. In the ad, a woman who looked suspiciously like my mother thumbed through her own stack of bills. She presented her husband with the electric bill, which no doubt was for enough kilowatt hours to send the house into its own orbit around the earth. Her eyes widened as he fell to the floor in a dead faint. “Maybe,” she said in a high-pitched, trembling voice, “I should work part-time at the Internal Revenue Service during the tax season.”

Bingo! I envisioned myself at the IRS, poring over some unfortunate soul’s tax return, while my co-workers (who all looked like Caspar Weinberger) huddled over calculators. I dreamed of financial burdens lifted and prestige within the community as I thought of the wonderful benefits Uncle Sam is famous for, not to mention the pay scale. Before the ad ended, I was dialing the number that flashed across the screen.

Every year, the Internal Revenue Service Center in Austin hires about two thousand additional workers to process the truckloads of tax returns that arrive during the peak season, from January through April. Each temporary employee may work a few days or as long as six months. In the unit for which I worked, the sole requirement for the job is to pass the GS Level 2 or 3 Civil Service examination, which tests one’s ability to read, alphabetize, and solve rudimentary arithmetic problems. No personal interviews are conducted, and the only background investigation is a check to see that the applicant isn’t on the IRS’s list of delinquent accounts. I didn’t realize at the time that these hiring practices would result in the strangest assortment of people ever gathered under one roof.

On my first morning at work I noticed that of the fifty or so new employees assembled, not many looked like the housewife in the commercial. I gazed for a moment at a lovely, though unusually tall, woman. When I heard her speak, I was a little jarred to realize that she was, in fact, a man. Standing next to him was a teenage boy—or so I thought until I noticed bra straps showing through her Izod. Later the young woman confided to me that she did, indeed, want to be a boy. The most significant trait among the group as a whole was obesity—I had never seen so many outstandingly large people. It was distressing to see women who gasped for breath as they walked. One of them was carrying an ice cooler for a lunch box.

Our manager, a pleasant-looking woman in her forties, explained our employment status. We had been classified as “intermittents,” which meant that we would be called on only during periods when there was more work than the regular staff could handle, such as the peak season. We might at times be called in and then asked to leave if the work ran out. We would receive no benefits: no sick leave, no accrued vacation time, no health insurance. We would be paid by the hour at somewhat higher than the minimum wage, and our tour of duty, as the workday was called, would be from 6 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. Our thirty-minute lunch break would be unpaid. My vision of respectable, secure government employment was rapidly being replaced with an image of sweatshop labor.

Our manager went on to say that a new dress code would be enforced and that it would no longer be permissible to wear bathing suits to work. Also, she said, we must wear shoes. I wondered if I’d heard correctly. Barefoot workers in bathing suits at the Internal Revenue Service? I looked around to see if Rod Serling was standing in the corner, ready to announce that I’d entered the fifth dimension.

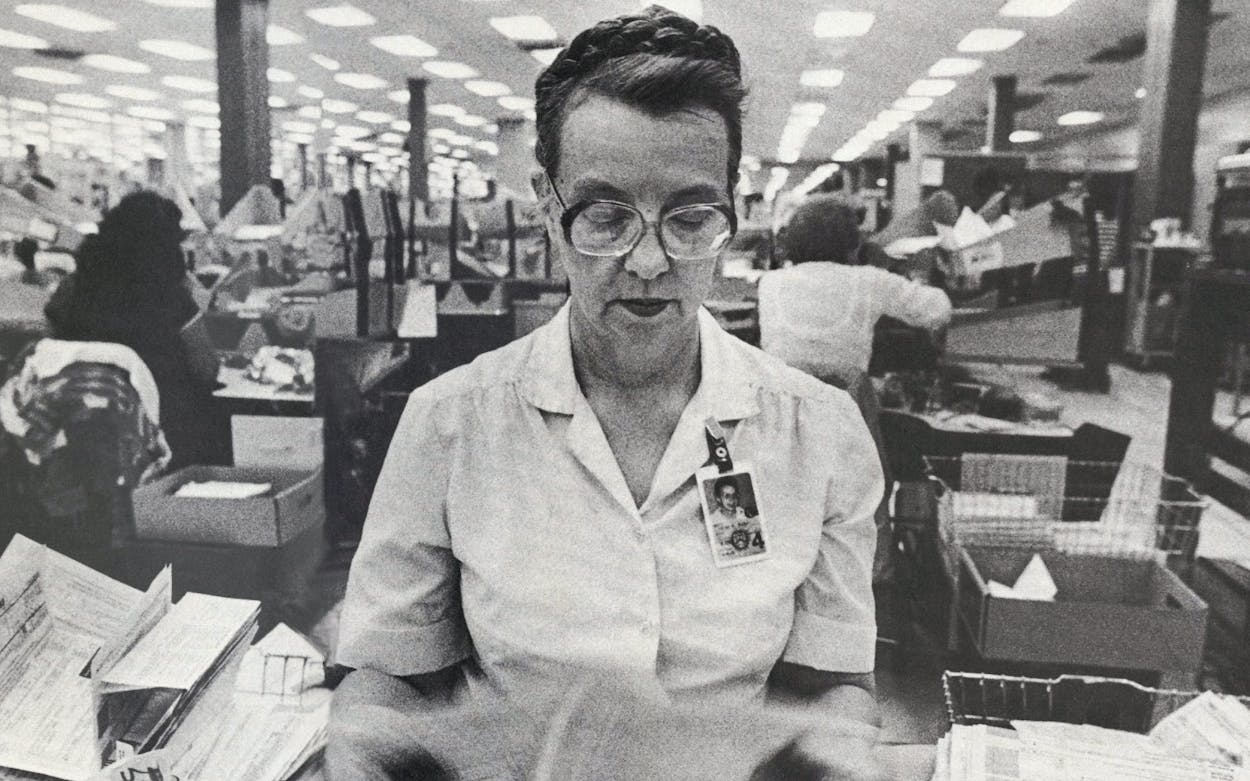

We were told that we would be doing “extraction,” which is officialese for opening the mail. (In all fairness, I should state that the mail was to be processed first by an Omnisort, a machine that sorts envelopes by bar code, sands off their bottoms, and stacks them upside down in cardboard boxes. The envelopes would then be sent to us.) We visited the enormous room where we would be working, which was furnished with row after row of specially designed desks called Tingle tables, so named for their inventor, James Tingle. Tingle tables in an extraction unit—it sounded both delightful and sinister, rather like a chiropractor who practices dentistry. There were about 120 of the Tingle tables in all. Five stacks of sorting bins, three bins to a stack, lined the outer edge of each tabletop; the work space left in the middle was barely large enough to open a return on. A small, elbow-high ledge, made to hold a box of mail, jutted out on the table’s left-hand side. In the middle of the room sat the managers and work leaders, decidedly the upper echelon, watching over the rest of the workers from their executive desks.

That day we learned the procedures we would be following as we worked. Once we had removed the contents from an envelope, our next task would be to identify the type of return. In 1983 there were nine major classifications: 1040, 1040A, 1040EZ, 1040ES, 1120, 1065, 1041, the 940 family, and tax-return correspondence. All other forms were to be lumped together in a “miscellaneous” category.

Each type of return had its own rules. 1040’s were considered business returns if an amount was written on line 12 or line 19; unsigned 1040’s and 1040’s without a W-2 form called for special handling; past-due 940’s and 940’s that had a remittance but not an IRS computer-generated label went to miscellaneous. The extractor had to compare the amount of any payment with the amount owed; if the two numbers differed, the return was sorted as a partial-payment return, even if the sender had overpaid. From moment to moment we would determine, for example, whether the 1040 return in hand was a 1040 business with-remit full-paid, a 1040 business with-remit partial-paid, a 1040 business non-remit, or a 1040 non-business. But before stuffing a return into the appropriate bin, we had to take certain measures to reduce errors farther down the line.

That brought us to the weighty matter of stapling. Each Tingle table came equipped with an automatic stapler. We were later to discover that these devices behaved like finger-eating demons when accidentally breathed upon but got sulky when presented with documents to staple. The first ten minutes of each day were usually spent finding a stapler that worked and voicing loud complaints about the night-shift workers who had used the desks before us. It was a rare return that came in with its various parts stapled in the proper order. Often the taxpayer, in his eagerness to explain some problem, stapled a letter to the front of the return. Our job was to remove the letter immediately, place it in back of the return along with anything else that had come in the envelope (most commonly cartoons and prayers), and restaple the bundle in the upper left-hand corner. No one would look at the letter again unless the computer kicked out the return for some error. W-2’s were also stapled to the return, front and center.

In addition to concentrating on our stapling and sorting, we had to ensure that all pre-1982 returns were kept separate from the 1982 ones, that envelopes belonging to prior years’ returns were not discarded, that certain business returns were stamped “Received,” and that all remittances in excess of $10,000 were put on a pole to our right for immediate pickup. We later found that whenever we finally understood all the categories and special rules, a memo would circulate changing them just enough to mix everybody up.

Unfortunately, the number of “sorts” exceeded the number of bins available; most of us ended up dividing the wedge-shaped spaces between the bins with cardboard so they could hold more sorts. Perhaps the most interesting sort was the “missent” category—mail that had reached the IRS by mistake. In thousands of envelopes we found mortgage payments, birthday cards, love letters, loan applications, food coupons, and utility bills. Never again will I sneer when someone tells me the check is in the mail. Missent mail was reinserted into the envelope with a stuffer that read, “Opened by mistake by the IRS,” and sent back to the mail room, where it was resealed and returned to the post office. I imagined how paranoid the person must have felt whose bank statement was returned with that note. But he needn’t have worried—Big Brother was definitely not watching.

The first week of extracting was a shakedown period during which we, the army of new recruits, had time to think of little else except the job. Our work was tedious and nerve-racking, requiring us to grab envelopes and remove the contents at breakneck speed. Hand-eye coordination was imperative. We were expected to extract, process, and sort at least five returns per minute, or three hundred per hour, on the average. Altogether, 250,000 pieces of mail were pushed through the two shifts of extractors during that April peak. As we labored, work leaders paced up and down the rows exhorting us to work faster. Plantation overseers had nothing on those guys—it wouldn’t have surprised me to see them atop horses with whips at their sides. Other workers, called runners, walked up and down the aisles all day long, picking up the sorted returns from our bins. They then bundled their piles of sorts with huge rubber bands and placed them in labeled wire baskets at one end of the room. At any time, the sorted returns in an extractor’s bin could be pulled and examined by someone from “quality review.” Processing errors were recorded against the department and the person who made the error.

We never saw the returns after the runners picked them up. All “with-remit” baskets were sent immediately to the deposit department, where checks were separated from returns. The checks were listed on Form 813, a bank deposit sheet. The returns were encoded by machine with the payment amount and a document locator number, or DLN. (The DLN is always printed on the upper right-hand comer of IRS correspondence to taxpayers, who must refer to it when consulting the IRS about a problem.) Returns without remittances went to yet another department, where someone stamped DLNs on them. All the returns were then sent in batches of one hundred to the returns analysis department, where they were checked, edited, and coded.

From there they went on to data processing. A data transcriber entered information from the returns into a computer, which determined whether mistakes had been made and whether the returns involved any audit issues. By that time each return had been handled by workers in a minimum of four departments. Though people who sent in routine returns requesting refunds usually received a check within six weeks, any kind of foul-up could significantly delay their check. If an error had been made, the return was put into a “loop” process of finding, correcting, and reinputting the data.

On occasion, it was the taxpayers who caused problems, by sending cash through the mail. An extractor who found cash in a return was supposed to take the return and the money immediately to a cashier, who sat near the managers in the middle of the room. Some of the cash, however, disappeared. Oddly, it wasn’t large sums that were stolen but $5 and $10 bills. When a woman was caught stealing during my shift, she was escorted from the room. A manager later told me that typically about one per cent of the extraction-unit employees were caught stealing. If an offender refused to resign, he was fired, but if he did resign, nothing was written on his official record. All cases of theft were turned over to the federal prosecutor, but charges were seldom pressed.

Though the work was not exciting, I soon discovered that my fellow workers were. Intermittents were subject to new desk assignments every ten days or so, a practice that was followed to “increase productivity,” I was told. We interpreted that as meaning “cut out the talking.” In the beginning I resented that treatment; I could see us all rising up like the half-human, half-animal creatures in the movie The Island of Dr. Moreau and demanding, “Are we not men?” But I came to appreciate the frequent moves, for they allowed me to meet an amazing range of people.

During my months of extracting, I talked to housewives and college students and retirees. I talked to more gay men than I had ever seen in one place, except at a gay bar. One of them used to kneel down beside another and sing lilting ballads to him as he worked. As much as I enjoyed overhearing the songs, I was always relieved when a work leader appeared, restoring order in our row. There seemed to be an equal number of lesbians, one of whom had the irritating habit of making obscene phone calls to the better-looking males and females in the group.

I talked to a writer who, like me, had to make ends meet while waiting for his big break. He was outrageously handsome, and he inspired all kinds of responses, from romantic fantasies to playfully hatched plots for murdering his wife. When he walked through the unit, women stopped whatever they were doing, sat straighter, smoothed their clothing, and smiled directly at him. Even from across the room, they noticed him. “Look! There he goes!” a woman well past sixty exclaimed. Being severely myopic, I couldn’t see the object of her adoration clearly, so a nineteen-year-old on my left clarified, “You know, the hunk.”

A young transvestite showed me his beauty-contest photos and told me he hoped to become a makeup consultant. He certainly knew his craft; made up as a woman, he was gorgeous. During the five months that we worked together, his breasts grew steadily until they were larger than mine. I was too embarrassed to ask how he had accomplished this, but I was envious. I sat next to a man who had four college degrees but couldn’t hold down a steady job. I talked to a mental-hospital outpatient who struggled daily with his fear of looking into people’s eyes. I befriended a woman who had a history of being abused. The last time I saw her, she had a broken nose. “This time,” she said softly, “I’m pressing charges.”

We represented the full spectrum of ethnic and socioeconomic variance. The women outnumbered the men three to one. We were artists, actors, writers, musicians, washouts from high-level professions. We had arrest records and troubled pasts. We suffered from heart trouble, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, diabetes, chronic bronchitis, arthritis, anorexia, drug dependence, alcoholism, and nymphomania.

For a time I worked next to a plain-looking 35-year-old woman who generally kept to herself. At the start of each day, she was reserved, hardly speaking, very concerned that she keep up her quota. Her routine never varied. She arranged her desk for work, put her pencil and stamp pad in just the right spot, took her thermos out of her purse, poured a cup of coffee, and started to work. As the morning wore on, she became friendlier, more animated. By midmorning, which coincided with the emptying of her thermos, she was the life of the party and gave off the unmistakable aroma of liquor.

The most enjoyable time for me was when I sat next to a black woman in her thirties. She was cheerful, bright, and articulate, and she spent her workday listening to gospel music on her tape player. We talked about Maya Angelou and James Baldwin, and she told me about the horrid influence of the devil on today’s society. The latter topic sparked lively debates among our co-workers about fundamentalism. Several of them deluged me with pamphlets about the pervasiveness of the devil’s influence. All this because I had voiced my belief that people, not some demonic force, were responsible for the misery in the world.

The camaraderie among intermittents during the peak was similar to that among combat soldiers. We were working for the government under stressful conditions, doing the dirty work while the officers claimed all the glory. We knew we were there only for the duration and that once the job was done, we would probably never see each other again. And so, working side by side in a frenzy, we divulged to each other the most intimate and sometimes shocking details of our lives. There we would be, snatching envelopes, ripping out the contents, stapling loose documents, matching money amounts, sorting—and discussing our crummy sex lives with total strangers.

After a while, I began to wonder if anyone there had a normal sex life. I talked with a woman who had not slept with her husband in more than ten years. A newlywed complained that her husband wasn’t interested in sex, and she detailed the extremes to which she had gone to arouse him. A man piped up, “Well, at least you don’t have to worry about getting AIDS, honey.” I listened to conversations that I had thought existed only in the minds of writers for men’s magazines. I witnessed romances bud, bloom, and wither over the course of a week.

Once I had become sufficiently intrigued by my co-workers, I began having a good time at work. But though I found the personnel fascinating, the IRS’s system of hiring was not necessarily the best for taxpayers who wanted their returns processed quickly and accurately. One day an extractor commented, “There are so many people here with that glazed-over look. I suppose it’s good that they can find gainful employment, but it does make one wonder about the quality of the work.”

That year two members of my family had their returns garbled. My brother-in-law sent in a routine 1040 and was confidently awaiting his refund when he received a letter from the IRS stating that his gambling losses were not an allowable deduction and that he owed the government money. He was apoplectic as he read the letter to me. The only gambling he did was making an occasional bet with his wife, and not only had he not claimed gambling losses but he didn’t even know how to claim them. I assured him that some simple error must have occurred and urged him to contact the IRS. Some seven months later he finally received his refund. My father was also informed that he owed the IRS money. As it turned out, the IRS had lost all record of his W-2 forms during processing. I was an IRS veteran by then, and I suspected that these mistakes were evidence of a much larger problem. Workers who are not encouraged to have a shred of pride about their jobs are not going to care if they make a mistake. In the mad rush to keep things moving, returns all too frequently got mixed together, and pieces got lost.

Each week we received a computer printout called an individual performance record, which listed our error percentage rate and our standing within the unit. We were told that our IPRs determined who would be kept on after the peak and who would be “furloughed.” What we weren’t told was that a written evaluation of our performance by our group manager had a strong influence. Politically savvy people who kissed up to their manager more often retained a position after the peak. When I confronted a higher manager about this, he acknowledged that favoritism did occur but said that they tried to weed out that kind of manager.

At the IRS April is indeed the cruelest month. We were asked to work ten hours a day, seven days a week. Tempers flared, tears were shed, and people came to blows. When I found out that we would not be paid more than time and a half for working Sundays, I was outraged because I had been told that we would get more than that for Sundays. I was among those who succumbed to the temptation to tell off management. “Yes,” my manager said, “there is a Sunday differential paid to permanent employees and seasonals but not to intermittents.” (Seasonals are part-time workers who get benefits, a step up from intermittents.)

“But we are all doing the same work and working the same hours,” I countered.

“The difference is that it is not your regular tour of duty,” she said.

I felt obliged to object, on behalf of all the intermittents pretending not to overhear our argument.

When the peak finally ended, my fellow extractors and I were in a mood to celebrate. We had made it through! In previous years, the manager of the extraction unit had hosted a party to reward the people who had worked like horses to push the returns onward. That year there was no such party, and I felt cheated with the standard job-well-done speech. After all, during that particular peak we had started with the lowest rating for service-center efficiency throughout the nation (number ten) and had raised ourselves to number three. Soon an invitation was circulated to a we-survived-the-peak-of-’83 party, hosted by two women in the unit.

After April the mail fell off drastically, and about a hundred intermittents were released from the extraction unit. With so many of the interesting characters gone, the work was never again as much fun for me. I was given a different job scanning business returns and separating out those with specific amounts, though I was never told why this was necessary. A few weeks later I furloughed myself. The afternoon that I left, my manager told me that the center had seen a better quality of intermittents that year, a cut above the usual. “Before,” she said, “it was a real zoo.”

Martha Ebersole is a freelance writer who lives on a ranch near Harwood. Her play Texas Tacky was recently produced at the Bastrop Opera House.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Austin