About every six months I wake panting in the night with the recurrent nightmare that I am committed to an insane asylum for life. There are the cold and detached omnipotent doctors with notebooks in their hands, and they ask at what age did I first have sex, is there a history of mental illness in my family, and have you ever been hospitalized before, Mr. Snow? I wake long before dawn to sit suddenly up in bed and say: Thank God, it was just a bad dream. After you have been locked up you may feel it too—a burden you can never shake. It will paralyze your psyche and you will sigh and think, somehow I’ve got to come out of this, and you will say to yourself—wait a minute, just relax, you’re OK now, kid, you’ll be OK.

I am OK. For a long time I wasn’t. During the last ten years or so I have done time in seven mental institutions. In 1974 I was convinced I would be President of the United States in 1976. Election day has now passed, and, not surprisingly, I wasn’t elected. More important, I have recovered.

In my case it was necessary to come to terms with a specified drug program. I am a legalized addict. My dose: 100 milligrams of Thorazine and 60 milligrams of Stelazine daily. I don’t feel this dope at all, but have been told it is strong enough to flatten a normal person. It keeps me—as the doctors agree—sane and in good spirits. Without the brain candy, as I call it, I would go—zoom—right back into the bin. I’ve made the institution scene enough already to be familiar with what it’s like and to know I don’t want to go back.

Nobody ever told me clearly that I am OK; it was a conclusion I had to draw myself. I first began to think I was in bad shape around 1964, when I lost my first major girl friend and flunked out of Texas Tech. I experienced a typical sophomoric sense of gloom, I felt nobody understood how much I was suffering. Prior to that time I had, like everyone else, experienced sorrow but never despair; my depression was anger turned inward. My brother, an aeronautical engineer who specializes in the production of agricultural aircraft in North Texas, tried to get me to enter the Timberlawn sanatorium in Dallas. I saw the head man, and he said, “Timberlawn is a good place for a depressed man to be.”

The only trouble was that by entering I knew I would become more depressed by being depressed in the first place. No dice. I turned down the chance. I was reinstated at Tech the following year. By 1965, however, my sister, a musician who lives in Lubbock, talked me out of marrying a gifted but immature piano student I was having a romance with and suggested that I begin psychotherapy. I had been drinking Gallo instead of studying for exams and had turned down a chance for a teaching assistantship in English to attend the Tech graduate school. Because I was still depressed, I took up my sister’s offer.

My first psychiatrist was a middle-aged fatherly man with gray hair and black horn-rimmed glasses. Soon after our sessions began he told me, “If you want to change, it’ll take about a year.” I was all for it. My belief now is that you can change, but you will do so only within the boundaries of who you already are. I did not know that then, back when I was 25 and impatient for self-improvement. My siblings were successful by that age, and the pressure was on me to shape up fast. Why hadn’t I produced something by then? There is a sense of duty to excel in my family. It has tormented me. I have to make it all the way or I won’t make it at all. I was not trained to settle for less. And the seed of doubt concerning my relative sanity was stuck into my mind like a termite in a matchbox. If I was supposed to change, then something must have been the matter with me.

The doctor was eventually to become a nagging problem, saying, in his nasal way, “Why do you always defeat yourself just when you’re about to become successful at something?” He seemed to think I failed at things deliberately in order to get back at my brother, who had been a friendly but somewhat strict substitute male figure to me after my father’s death when I was ten. Doggedly he stuck to this thesis, and a terrible sense of despair began to well in me—it was a young man’s funk, supplemented by a gnawing fear of insanity. Was he right or wrong? For most of my life I had been criticized for not sticking to any one thing. I felt that my doctor’s idea and my family’s anxiety about my sense of identity were premature concerns which interfered with a logical and natural form of growth. I had not “made it” by 25, so the subsequent reasoning, by family and doctor alike, was that I needed professional help. I was not against professional help. I just never felt that my doctor had it figured right. Out of millions of possibilities he thought he knew just what my problem was, and his arrogance was not especially conducive to my well-being.

In 1966 I became a night clerk in Lubbock’s Caprock Hotel, where I read Thoreau and Emerson and tried to write a novel. Then the anxiety came, a shock in the night, a pure and simple fear. An anxiety attack occurs when a detached and ironic portion of the mind watches the imbecilities of another part of you and is unable to laugh or cry. When you watch yourself too closely you get scared. You wonder, “Am I normal?” and the fear that you may not be is terrifying. Or so it was with me. I quit the job and the doctor gave me a drug called Serax, which produces a mellow glow similar to two Cuba libres. I got high on them and felt grateful toward my benevolent mentor. Idle, however, and indisposed, suffering from writer’s block as well as a sense of panic about my future, my inner sense of dread surfaced, and I became chronically depressed in a way that would make Hamlet seem like Mary Poppins. I checked into the psychiatric ward of Lubbock’s Methodist Hospital. My doctor (the same one as before) prescribed sleeping shots every four hours and I was awake only during meals. Consequently that stay in Methodist was uneventful. It was just a clean, well-lighted ward.

To try to beat boredom when I wasn’t reading or asleep, I began work on a plastic model kit of a BMW motorcycle. For two or three days I fumbled with this tedious task. I was a bike buff at the time and really wanted to get that model into immaculate shape. I wanted to pretend it was a real machine, polished and ready to ride. When it was nearly finished I realized that a piece of the frame was missing. There was no way the BMW could be complete without it. Thwarted, desolate, in need of love and purpose, I took the model with its unfinished parts and put it on the arts and crafts table to await the interest possibly of a more patient soul. I went home to Harlingen after that, watched Hollywood Squares, and tried to forget the BMW.

There I found another psychiatrist, a fat young man who also wore black horn-rimmed glasses. He posed as an “existential psychiatrist.” That meant he thought people were screwed up and so was the world but that he could adjust you to it anyway. This guy said to me, “You’re screwed up.” And I wanted to say, “That might be true, but if you know so much why are you so fat?”

I hung around Harlingen a few months then went back to Tech. I was 27, still “going to school.” But I still had the Serax, which made my life a comfortable illusion, even though my first doctor’s nasal monotone had become a voice I could not live without: Why do you always defeat yourself just when you’re about to become successful at something?

But I partied my way through another year at Tech, then dropped out to go to Austin in the fall of 1968. During that time I saw Gloria Steinem on television and decided immediately that when I became rich and famous, she would be my girl. I was slipping away without knowing it. I found a nice, quiet furnished room and ordered beer by the case while writing a zany, disordered, and pretentious novel I soon became convinced would sell well. One night when I was drinking beer in a place called the Orange Bull, I called a friend in New York. “Come on up,” he said. “OK,” I said. I would go to New York, I dreamed (more than ever caught up and involved with fantasy), and publish my novel.

Another friend in New York allowed me to stay in Stratford, Connecticut, until the spring of 1969. Stratford was a good place to hole up with my work, I imagined, and there would be time to revise my novel. Alone most of the time, I drank wine and wrote modest short stories and fooled around with my novel some. I then had a traumatic relationship with a woman. When spring came I was a borderline case. A friend of a friend allowed me to sublet his apartment in the West Village. I slipped on into madness the way one gingerly tests the water temperature in a bathtub. And the good times began to roll. Soon it was summer of 1969, and my spirits were high with the times.

I drank at the Village Gate, where I met by chance the jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal and other gifted New York jazz musicians. I was shedding a frustrated career as a jazzman by mixing with the best, if not on a performing basis. I tentatively planned to take piano lessons from one of the musicians. Because I was running up a drinking bill, however, I got a job as a typist to support the fun.

At that time Norman Mailer was running for mayor of New York City, and I went around the streets campaigning for Mailer like the greatest political crackpot ever. I waved at helicopters. I slugged rotgut wine with winos. I was virtually uninhibited, roaming into nightclubs drunk, and crazy at the same time, complimenting the best-looking women present, sending notes to waitresses on napkins, dancing frenetically; it came to me that I was a very important political figure in Manhattan. Symbols and associations and similes and metaphors and analogies flowed into me in a hopelessly confused way. I thought: Norman Mailer will be mayor and I will elect him somehow someway it’s got to be possible and then I will compose music for the black royalty at the Village Gate and no telling when Gloria will show up and see how successful I have been since my struggle began but now everything must be the way I, the Texas Kid, King Edward, the Snows of Kilimanjaro and I like New York in June how about you do you ever think, Texas kid, think for a minute that there was nonsense to despair occurring earlier and now it’s all over and I will win but I must keep moving because great generals always do to the end and the Texas Kid will make history interesting. I was insane.

Schizoid thought is free association moving at such a speed that formal logic is impossible. A psychiatrist can say the patient has lost contact with reality as we know it, that the world appears to the insane from a highly subjective point of view with hallucinations and delusions in which the patient experiences an inability to connect outside sensations with interior interpretations of data. Sometimes it is not unpleasant. I was to have the concern later that certain political factions were plotting against me, yet I have also felt an aesthetic which incorporates total dedication to a love of life, a spiritual connection, and a notion that there is purpose to life.

Finally, I was taken to Bellevue Hospital by police for throwing a rubber ball at vehicles at a busy intersection; I would bounce the ball off the sides of buses and trucks, then run gleefully into traffic to catch the ball in this spontaneous and dangerous game of my own invention. I told the cops I was waiting for a parade.

The parade would be through New York; I was to become Acting President of the United States because I was not old enough to be the official President; I would ride in a gold Cadillac convertible with Steinem and other political notables of various races and creeds. I had concocted that fantasy the night before while shouting peculiar messages into the dusk; I thought my rantings would be transmitted via satellite around the world, which of course I thought I had saved.

In Bellevue a smiling flunky asked, “Do you hear voices, Mr. Snow?”

“Yes, I hear yours right now,” I said. He smiled hideously in a patronizing understanding way and gave me a shot. I had not slept for three days. They gave me a bed, and I thought I was to be executed. But in my last few moments of wakefulness I thought of The Sun Also Rises and reckoned the sun would be up as usual in the morning and I would be an international hero.

For three weeks I waited for the parade, thinking merrily that I was placed in isolation to protect me until the public was ready for my appearance. After I had been admitted, I told the interviewing psychiatrists that I was Acting President of the United States.

“You mean you’re President when President Nixon is away?” one of them asked.

“No,” I said, “I mean I’m Acting President only in the sense that I am Acting President of this room.”

They didn’t understand. I knew remotely that they were doctors and that I had to be careful about what I said. My family was notified. My brother flew to New York, came to Bellevue and said, “Ed, do you want to stay in New York or go back to Texas?”

And I so loved New York that I replied, “I would rather stay in New York,” and wandered off. He didn’t appear worried and flew back to Texas.

In the meantime I kept waiting. Glazed-eyed blacks were pinned to beds with restraints; there was the clanging and whanging of trays at mealtime. I heard voices calling to me: Texas Kid Texas Kid Texas Kid Texas Kid is waiting for Gloria Gloria Gloria. I wrote a poem to Gloria on the wall with a borrowed pencil, averaging one line per day; at the end of a week I was made to erase it. There would be no romantic graffiti in Bellevue.

My illness was diagnosed as acute schizophrenia, and I was given medication. My “sentence” was for 60 days, and I was to be transferred to Central Islip State Hospital on Long Island. For the time being, my refuge in Bellevue was with the down-and-out whites of the city who needed food and shelter, criminals, hustlers, and con men, frightened men, pathetic men, degenerates, poor lost and anonymous Puerto Ricans, and a powerful black in particular who should have been a running back for the Dallas Cowboys. I would pace through the hall in a frenzy, and he would see me coming, hiss obscenities at me and smash his fist into the lockers, as though he wanted to hit me. They finally put him in a straitjacket, and because he was crippled now I would taunt him, and he would grin savagely in retribution. One day he worked the straitjacket over his shoulders and with his hands almost free, smiled murderously at me. I summoned an aide before he could attack. He was finally shipped away. Co-patients, however, can be helpful. A young heroin addict told me, “Hey, man, you better come off this crap about being President.” I did not mention it again.

I came to reality at the time of my transfer to Central Islip, which lives up to its proper designation as an “insane asylum.” Here there were huge grounds with great green trees and a gigantic network of crumbling buildings to accommodate those of us who had been displaced from the mainstream of American life.

They kept me on a locked ward on the second floor for ten days, and fear crept through my belly like a tapeworm. It did not take me too long to learn the rules. An attendant had the courtesy one day to explain briefly how to get out. “If you screw up, they’ll send you upstairs and that’s where they throw away the key and you can forget it. But if you behave you’ll be sent down to the first floor. Then you’re on your way to a discharge.”

Oh, to get to the first floor! Through the bars on the windows I peered at the grounds and watched people sitting on wooden tables as though Islip was really a picnic ground. In 1962 I had ridden my Triumph motorcycle through such a landscape, and those past days of freedom pulled at the gut, wistfully embroidered my vision with nostalgia—I thought of my college days, home, family, loved ones, and here I was behind bars. I would sit on the toilet which had no stall for privacy and think, will I get out? When? What do I do now?

Finally a nurse came to the sanest of the inmates and said to us, “You guys see the doctor today. Look sharp.”

It was the turning point. I would go either upstairs or downstairs or remain in purgatory on the second floor.

“What happened in New York City?” a doctor asked in his first-floor office.

“I got excited and carried away by it all,” I said, trembling. “I was involved with the Mailer campaign and got excited.”

“Just a little flip-out?” he asked cautiously.

“Yes, I just flipped out. For the first time.”

“OK,” he said and wrote something down. I had my grounds privileges.

In the meantime, my brother arranged to have me enter Timberlawn, and after almost two more months at Islip, I was released and flew to Texas. Timberlawn was my third bin in less than three months. Timberlawn is for the maladjusted wealthy bourgeoisie. The patients had a deranged look of opulence, of too much luxury and blurred perceptions. They complained, they swore, they thought their hang-ups had never been known before in human history, they demanded attention and fought for prestige. In my ward was a psychiatrist who had committed himself because of a “depressive cycle,” thinking he needed “observation.” He worked in a state hospital. He spoke of literally fighting his patients when they became unruly. In Timberlawn he was naturally inclined to cooperate, placing himself in the care and jurisdiction of the doctors. Of course, in the country of the insane, the psychiatrist is king. Some of the patients asked this guy for advice.

In Timberlawn there are meetings, parties, sports, occupational therapy, a swimming pool, and regularly scheduled “classes” to attend like school. It was, it seemed to me, a sterile and detached abstract invention by administrators who had tried to achieve utopia and failed. One young man was restricted to his ward because he didn’t want to swim when he was ordered to because the water was chilly.

My “administrative psychiatrist” was a woman, and I told her about the New York episode briefly. “Sounds like you need to stay for several months,” she said. I did not agree, especially because I knew a menial job awaited me upon my discharge. Was my brother actually forking out roughly $400 a week to promote my conformity with accepted behavior? Yes, he was. My brother and I are on cordial terms, but the ethic of his generation is that work is the most important thing in life, a commendable thought under some circumstances, but I did not see the point in undergoing four months of therapy to emerge simply as a clerk-typist. I had no incentive to remain at Timberlawn.

There were laughs, though. One day a guy on my ward who was friends with the psychiatrist went to the swimming pool, grabbed a lawn chair, and jumped in, using the chair as a weight to make him drown. It is unclear as to how he would hold the chair underwater and drown at the same time, but he tried it. Later he said, “Hi, Ed baby,” when he saw me laughing in the hall outside his room. He was laughing, too, and was strapped to his bed.

I experienced the personal humiliation of being beaten by one of the more arrogant hipsters in a badminton tournament I was made to participate in. Another, an adolescent, called me insulting names and tried to egg me into a fight.

In Timberlawn there were division meetings where patients were allowed to air their frustrations under the supervision of doctors. There was a colony of a few hippie types who used four letter words for slang rather than impact. If anybody asked me how I felt about the place I would speak in a straight party line manner and say, “I’m beginning to like it here,” etc. During my visits in bins I have concocted other strategic lies to insure my discharge. But throughout these times I would harbor a ball of bitterness in my chest, thinking of the psychiatrists who had failed with me; by trying too hard not to be standard, I had failed with myself too. For that reason I am no longer angry at them.

I made my decision to leave Timberlawn during the night we did The Bunny Hop. It was to be performed at a party beside the pool. My job was to supervise the playing of recordings on a stereo set. Less than three months earlier I had seen Miles Davis in person in New York. The irony was exasperating. But we did the Bunny Hop—I did the Bunny Hop—we all did, yes, The Bunny Hop—yes, we really did The Bunny Hop. See how we recovered? We did The Bunny Hop to please the authorities, I guess, or, on the other hand, maybe my co-patients and I were precisely that damn dumb.

After my gig as a human record player, my next assignment was to emcee a talent show. I made an unauthorized phone call to get placed on restriction to avoid being an emcee. At that point I knew I had to leave fast. My visit had lasted six weeks, had not been even remotely effective in saving my soul. I was to leave “against medical advice,” as my administrative psychiatrist put it. “This is the next worse thing on your record to being committed.”

Quite early one morning in resplendent fall weather I swiftly made my exit. “You’ll never make it, Ed,” my administrative psychiatrist said on my way out.

I smiled, then quickly summoned a cab to the bus station. I went back to Lubbock pretending to look for a job until my money ran out. Then I returned to Harlingen. I lay around home about six months. Then, in the spring, of 1970, I began a book about schizophrenia. Remembering it all, my mind became immersed and cracked again. This time I went straight to the Rio Grande State Center for Mental Health and Mental Retardation (RGSC), which, luckily for me, is in Harlingen.

RGSC is my favorite bin. It’s a first-rate state hospital. A long hallway serves as a ward, with a dayroom at one end and a cafeteria at the other. A library was in the middle, and there I read Thomas Wolfe and Evelyn Waugh and played Debussy-like improvisations on the piano. The Mexican-American attendants were friendly and protective; they did their jobs, making us feel as comfortable as possible.

“Don’t worry, Eddy,” one of them said when I was very paranoid. “You’re not going to die, you’ll get out of here and be OK.” That is the kind of talk a patient needs to hear in the bin. They treated me as though I had nothing more serious than a wart to remove.

There was a pool table and movies, although my mind was going too fast to do much of either; I would scan a few pages of the books, then write letters or pretend to work on the book about schiz, very difficult subject matter if you’re crazy at the time. Yet I was permitted to have visitors and use the telephone. Mostly I would walk up and down the hall, applying everything to me in the assumption that I was the center of the universe, matching my surroundings with subjective associations. And I was given medication and released in two weeks.

I went back to Tech in the fall of 1970, and went on to graduate. I went crazy again and was caught and put away in Methodist Hospital again, which had improved a lot since 1966. Not only was it clean and well lighted but it had excellent meals and an arts and crafts center. The nurses were extremely generous about helping me. I was so active, though, I spent much of the time isolated from the others. I was doing only one thing wrong: I spat my medication into the toilet after pretending in front of the nurses to swallow it.

My sister visited me. “I’m going to run for President and marry Gloria Steinem,” I told her. “I love you, Eddy,” she said. She had me committed to Big Spring State Hospital a few days later. Upon my admission to Big Spring, an attendant made me strip and lie down and with practiced technique he inserted a thermometer in my rectum. This is what Big Spring is like. On my ward was poor Jimmy, a brain-damaged case who could only snarl. He enjoyed affectionate slapping, and the attendants would bait him, slapping him until he would snarl, leer, and slap back. I think Jimmy enjoyed it.

There was Billy, the happy idiot dwarf who loved to hug the doctor every morning. There were the quietly suffering Mexican-Americans who knew in their minds they were beaten and Big Spring was no place for a rebellion; they rolled cigarettes, murmured quietly among themselves, and caused no trouble. There was lost Cecil, an egocentric retarded 21-year-old boy who raced through the halls muttering, “I get discharge? I get discharge now? I get discharge soon?”

There was Jerry, the president of the ward who didn’t always have cigarettes—he’d been in the bin for four years and had accepted it and bragged of sexual exploits with women on the grounds or elsewhere. There was Jim who had been an agnostic but later “gave his life to Christ”; Jim complained often of thinking periodically that he was the confederate general J. E. B. Stuart. There was another Jim too, a quiet, friendly fellow who swore with me that we were through with beer forever, not to mention whiskey and wine—we blamed our being in the bin on alcohol. There was wild-eyed B.J., a black who spent half his time in lockup, as the isolation cells near the hall were called.

Everybody had to work at something or other for the maintenance of the hospital, a fair enough exchange if they treated you like a responsible human being. But we couldn’t even brush our teeth more than once a week. The attendants didn’t want to go to the trouble of opening our cubicles and doling out our possessions. So I would mop, clean toilets, and whatnot. Take trays to the men on lockup. Never in my life was I so depressed, and that’s saying a lot. Due to my depression, induced by the environment, I did not respond to medication.

I sat in a line, finally, to await my shock treatments. One by one they picked us off. During my stay at Big Spring I underwent ten shock treatments. I remember the last one was given cold turkey without benefit of the pacifying shot which puts you to sleep before they shoot the juice to you. The administrators of the shock machines said, “Just relax, hold your breath, take it easy.” They strapped me down and hooked the current to my brain. My body writhed and pressed against the restraints. I had a feeling that my legs were rising straight up in the air to flail, but they did not. I gasped for air, and the man kept saying, “Relax, hold your breath, take it easy.” And I thought somehow, in terror: I’ve got to be a writer and they are trying to destroy my brain. I do not remember the end of this session, though I can recall being fed toast with orange jam soon afterwards. I was discharged on the ninetieth day of my imprisonment after working in the hospital canteen wiping tables.

I went on to hold a string of jobs, the highest salary of which was $2.50 per hour. I ended up home again. I’ve had one more break—in New York again—since Big Spring. I wrote a lot of letters to celebrities. I sent Norman Mailer a deluded letter about what a great writer I was going to be, and he wrote back, on April 16, 1974, “Hey Snow, with your ambition, you need luck. Good luck.”

I returned to Rio Grande State Center in the summer of 1974, and because I have followed the medication then administered, I’m sane now. A year or so later I sent Mailer a card of apology. He replied on my thirty-sixth birthday, December 4, 1975: “Dear Mr. Snow, Well, this is just a line to thank you for your card and the kind compliment you include in it. Don’t be too concerned if your writing seems overly modest. Sometimes very good writing springs like a cat out of a quiet place. Yours sincerely, Norman Mailer.”

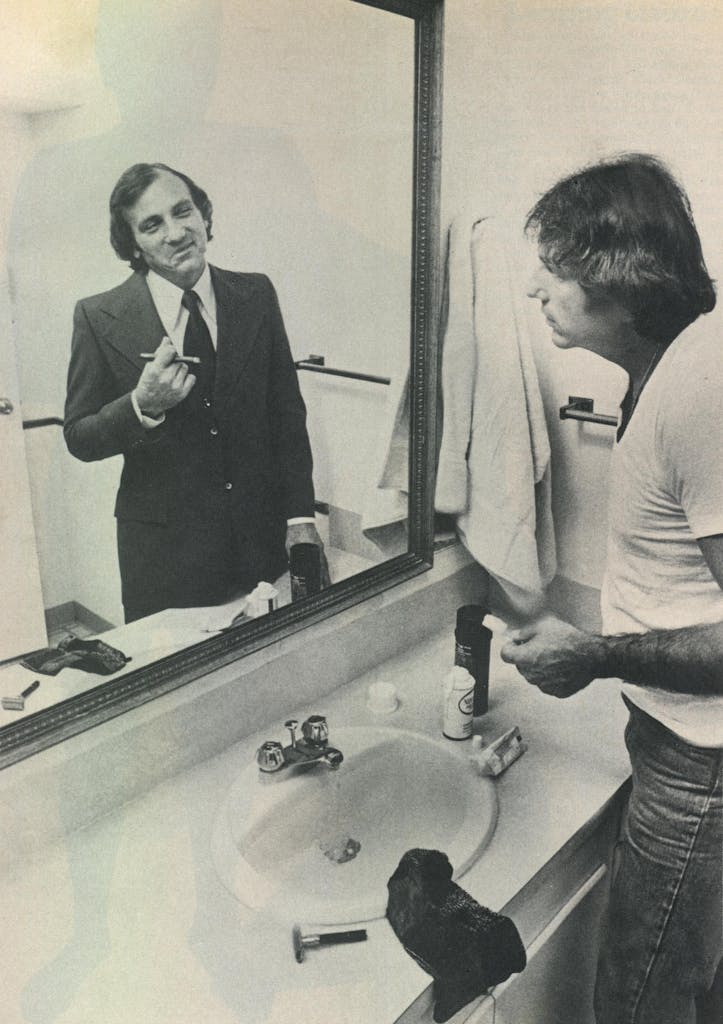

So that’s the end of my tale of lunacy. If you’re ever in the bin, though, and want to get out, here’s a tip: strategy is necessary—cooperate no matter what. A technique I have found effective is to look like hell for the first few days. Don’t bathe, shave, wear makeup, or even change clothes. Then gradually look better. Shave or wear makeup. Change your clothes after the third day. Bathe. Smile! If you give them progress they can see, you’ll have the most magnetic personality on your ward.

I don’t expect to ever again be in the bin. I attend group therapy at Rio Grande State Center weekly. A very nice woman in the group helped me overcome my post-discharge blues and start writing again.

And . . . the next time I have the Bad Dream I will sit up and think: maybe I have given hope to at least one fellow lunatic. Then I will go to the bathroom, return to my cot, and I will dream again of lost loves and forgotten places and faces and in the end I will know I’ve beaten it all. Which means, liberally speaking, I have recovered.