This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Elsewhere in these pages you will read of the high-finance deals of Maxxam CEO Charles Hurwitz, the fortune amassed by chicken magnate Bo Pilgrim, and the multimillion-dollar real estate play of Ross Perot, Jr. That’s just pocket change, folks. You want to talk Big Money? Let’s talk about the effect of John Hall’s decisions. We’re talking billions. Granted, it’s not his billions: Hall is the chairman of the three-member Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission, and his job description is to clean up the state’s none-too-pristine environment. Any company that wants to operate or expand a plant in Texas will almost surely need a TNRCC permit. From the humblest dairy farm to the biggest refinery, John Hall is in charge of anything that pollutes the air or the water. The muck stops here.

Hall has taken an entity that traditionally sided with business and turned it into an environmental force. TNRCC is a battleground where environmental and business lobbyists are constantly fighting over small differences with huge stakes. A proposed variation of five parts per billion in the amount of silver that can be discharged into public waters would have forced every dental office, x-ray facility, and photographic developer in Texas to buy $100,000 worth of cleanup equipment. (Hall agreed with business on that one.) Most of the time, though, Hall prefers to operate through what he calls jawboning—talking image-conscious industries into reducing pollution or getting them to buy homes in a contaminated neighborhood, without the need for formal TNRCC action.

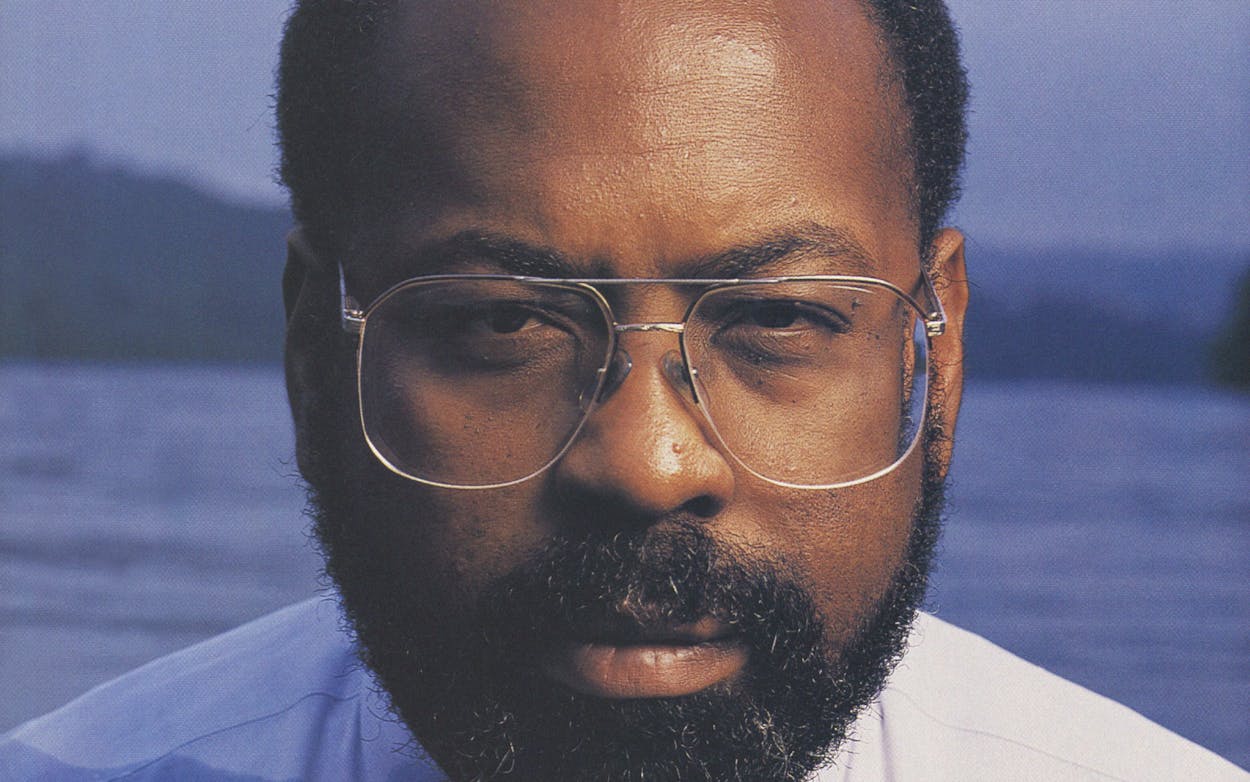

Hall, 40, is a government professional by training—he has a degree from the University of Texas’ Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs—with a politician’s knack for persuasion and a soft baritone that offsets his imposing six-foot-four-inch frame. He grew up as the fifth of nine children and picked cotton as a youth. He worked at the General Land Office and the Lower Colorado River Authority before Ann Richards’ office called in 1991 to offer him an unspecified position in the new administration. Hall said he wasn’t interested in a staff position or a social service agency. He wanted one job and one job only, and he got it.

The trouble is, the job is almost impossible. Hall has to enforce federal laws that keep getting stricter (and costlier) while he appeases the agency’s warring constituencies of business and environmentalists. “The biggest problem we have,” Hall says, “is that the process of getting a permit is too legalistic. Everybody is focused on winning by technicalities. Everybody takes absolute positions. Every case is controversial and people are polarized.

“Business wants us to issue permits faster. The enviros want us to delay. We passed a new rule that no contested case can take longer than a year. The enviros hate it. But business is just as bad. If they don’t get their permit, they run to the Legislature to complain.”

Sometimes the complaints get out of hand. The three commissioners received death threats from opponents of a new hazardous-waste incinerator in Channelview. They were escorted to the meeting in an armored car, and the room was filled with police officers in riot gear. The incinerator got its permit. Hall was unfazed: “I keep telling myself, ‘Remember, you’ve got an indoor job. It beats picking cotton.’ ”

- More About:

- TM Classics