This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury. You are here to consider the charges against John O’Quinn, a Houston plaintiff’s attorney whose ground-breaking victories in breast implant cases earned him a place this year on the National Law Journal’s list of the one hundred most influential lawyers in America. He had previously appeared on Forbes’s list of America’s best-earning lawyers, with an estimated 1988 income of $8 million—and that was before he started making real money. Mr. O’Quinn has been accused by politicians and opposing counsel of multiple counts of lawsuit abuse for regularly and wantonly inflicting great financial harm on large corporations. He has further been charged with damaging the Texas business climate—a complaint that has frequently been levied against plaintiff’s lawyers in recent years—by gouging corporate defendants for huge verdicts far in excess of the actual harm suffered by his clients. In three separate cases against Tenneco, Amoco, and Monsanto, he won jury awards totaling more than $1.1 billion.

You will hear the defendant admit, in his own words, to winning cases that a first-year law student would recognize as hopeless. You will hear how he frustrates judges, defies the ethical standards of the bar association, and—be warned, ladies and gentlemen—exerts his influence over juries.

Q. You have won two large jury verdicts for illnesses caused by leaking breast implants, one for $25 million, one for $18.5 million. But isn’t it true that a recent study at the Mayo Clinic found no evidence that leaking implants cause any diseases?

A. “That study was bought and paid for by the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons. I told the jury, ‘It’s not just legally wrong but morally wrong for any company to put a product on the market, that is going inside the human body, that has not been proven safe.’ ”

Isn’t that lawsuit abuse, Mr. O’Quinn? As any law student knows, the plaintiff has the burden of proof . You were supposed to prove that breast implants were unsafe. Didn’t you try to make the company show that implants were safe?

“I don’t see these cases as law school examinations. I see them as ethical issues. If you’re big enough, you don’t have to perform. Who suffers? Not the guys making the decision.

“The government wouldn’t do anything to help these women. The Food and Drug Administration wouldn’t do anything. The politicians wouldn’t do anything. All that’s left is twelve people in a jury box. I’m here to fight for these women because nobody else will.”

You won a $650 million verdict against Tenneco in Wharton County for breaking a contract to buy natural gas from your client, a small producer—far more than the value of the gas involved. Isn’t it true that all pipeline companies broke gas-purchase contracts when the market collapsed in the eighties, and most of these disputes were settled without a trial for less than the value of the gas involved?

“Have you been talking to the chamber of commerce? The Tenneco case was an object lesson in the corporate philosophy that greed is good. Greed is not good, Paul. Greed is bad.

“We talked about more than breach of contract. We talked about their chairman, James Ketelsen, who said at an energy conference, ‘Business thinking, not the law, must guide our decisions.’ I find that to be un-American, frankly. There’s a belief in this country that might makes right. Big companies don’t have to obey the law. They believe that.”

Wouldn ’t any business executive have said the same thing Ketelsen did? Every law student learns that the decision to break a contract is a business decision, not a moral decision. That is why the law does not impose punitive damages for breaking a contract. Yet your verdict against Tenneco included hundreds of millions of dollars in punitive damages.

“I never try the case that the other side thinks that I’m trying. They said I didn’t know how to try a business case. Well, I didn’t see this as just a business case. I had a little extra wrinkle that allowed the jury to award punitive damages. Tenneco’s purchasers were buying everything in sight, but its economists were warning top management about the market for gas. The jury found fraud, that Tenneco never intended to honor its contract.”

Didn’t you hire all the lawyers in Wharton County so that Tenneco wouldn’t have any hometown representation?

“It was just the top half. ”

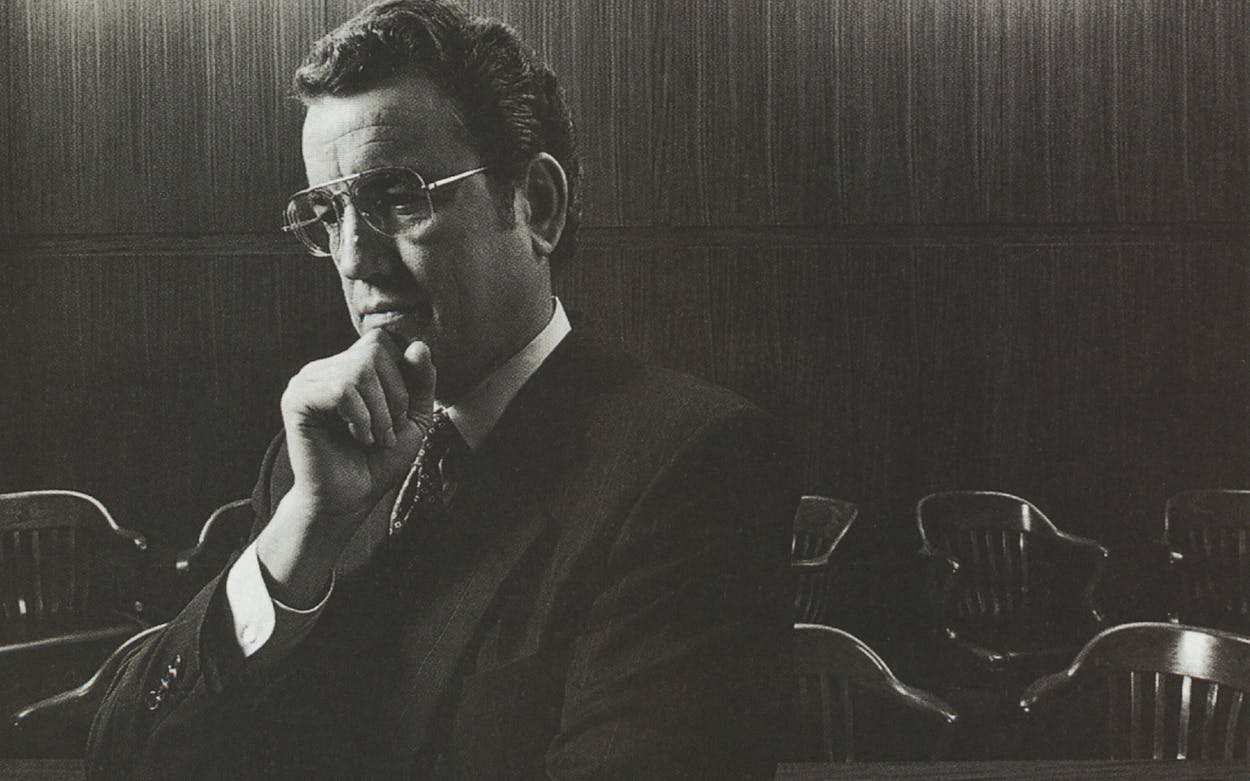

Let the record show that the defendant is a man of many voices. One minute he sounds like a teacher, making complex business and scientific deals sound simple. The next minute he sounds like a preacher inveighing against evil. But when you ask him about the efforts of the State Bar of Texas to discipline him for soliciting cases—also known as ambulance chasing—he is as taciturn and careful as a big-firm defense lawyer, which he started out to be. After graduating first in his law school class at the University of Houston in 1967, he worked at the bluechip Houston firm of Baker and Botts for two years, apprenticing under Finis Cowan, as good a courtroom lawyer as there was in Texas and a future federal judge. The young O’Quinn often found himself up against the city’s leading plaintiff’s firm. When the plaintiff’s firm needed a new hand in a hurry because two partners had died in a plane crash, they asked O’Quinn to join. “Follow your heart,” Cowan advised him, and he made the switch. Today, at 53, O’Quinn heads his own firm. His twenty-third-floor corner office on the north edge of downtown looks out at the citadels of business power that have come to be his lifelong enemy.

You won $8.5 million in Matagorda County for the death of a bull that was doused with undiluted insect spray by mistake. How can a bull be worth $8.5 million?

“Racehorse Haynes told me he couldn’t understand that either. I told you, I never try the case they think I’m going to try. That was a property damage case, but I tried it like a wrongful death case. A friend of mine had a paraplegic case against Exxon in Matagorda County at the same time. I told him, ‘I’ll get more for my dead bull than you’ll get for your paraplegic,’ and I did.”

Isn’t it true that wrongful death applies only to people?

“I always referred to that bull by name— Superman—or as ‘he.’ Never ‘it.’ I wanted the jury to think of him as a person. I asked the Aggie who ran the artificial insemination place where the injury occurred, ‘Did he have a personality?’ His testimony was, ‘He was dog gentle and liked to have his picture taken.’ ”

Doesn ’t the enormous amount of money that you win in these cases trouble your conscience just a little bit? Isn’t it true that a judge asked you once, after you won a $108 million verdict against Monsanto, at what point your conscience would start to feel “the first vibrations of shock”?

“I told him $500 million, Monsanto’s profits for the entire year. All I asked the jury to do is give the family of a man who died from exposure to benzene three months of Monsanto’s income.

“Here’s how corporate America works. They don’t care about the future. They don’t care about the products they make and whether they’re dangerous. Henry Ford had his name on his cars. He went down the assembly line to watch them being made. Do you think Roger Smith or anybody else at GM ever went to an assembly line? That’s why Japan is eating our lunch, and I’m tired of getting blamed for it.

“I believe that in America you still have the right to go before a judge and seek justice. I sincerely believe in what I’m doing.”

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury. There are certain facts that you should know about the defendant before you begin your deliberations. Mr. O’Quinn and the State Bar of Texas entered into an agreed judgment in 1989 in which he agreed not to contest charges that he had violated six professional disciplinary rules involving solicitation and fee splitting; he paid $38,000 to cover the bar’s costs and performed one hundred hours of community service. He has been involved in two disputes over jury tampering, neither of which resulted in disciplinary action; one incident involved a romance with a female juror that was found to have begun after O’Quinn’s case had been concluded.

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury. What is your verdict?

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Houston