This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It was March 2, 1993, Texas Independence Day, but instead of celebrating the day in Austin, state comptroller John Sharp found himself on an airplane bound for Washington, D.C., and his premiere as a national political player. The following afternoon, he stood on the South Lawn of the White House beside President Bill Clinton, facing the usual multitude of reporters and photograhers. The two men seemed an unlikely pair. With his sleepy eyes and moon-shaped face, Sharp looked out of place among the quick, nimble Washington types and the man who earned the nickname Slick Willie.

Yet here was Clinton, six weeks into his presidency, beset by battles over gays in the military and tax-dodging Cabinet appointees, turning for help to an obscure officeholder from Texas with a white-knight reputation as a budget cutter. In a few moments, Clinton would announce an audit of the federal budget, patterned after Sharp’s review of state spending in Texas. As they waited for the press conference to begin, Sharp eyed the long emerald-green expanse of grass, turned to Clinton, and said, “Nice lawn. Do you have to mow it yourself?”

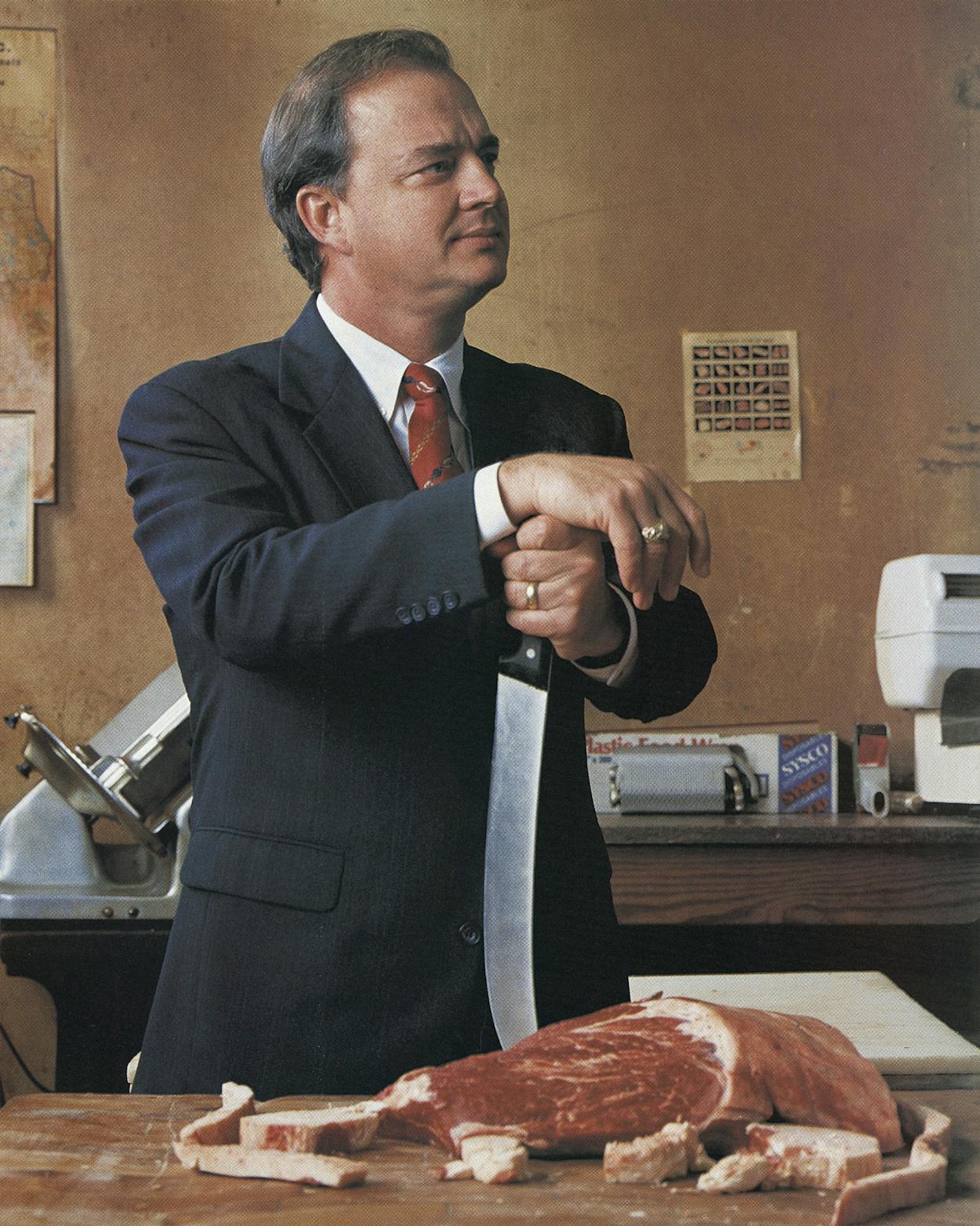

Standing behind the two men, Sharp’s wife, Charlotte, rolled her eyes. Was her husband—who had paid only twice to have their lawn mowed in fourteen years of married life—about to tell the president of the United States, in front of a national television audience, how much he could save by pushing a lawn mower himself? Fortunately, Sharp didn’t mention the lawn on television. But the episode reveals one reason why he has been so successful in establishing his reputation as a budget cutter: He practices what he preaches. His audits of state government, which have led to his current prominence, are an extension of his personal austerity; Sharp views himself as a thrifty good ol’ boy, an Aggie in perpetuity, a small-town boy from South Texas who made good. Everything about him—from the plug of Red Man that is usually lodged in his cheek to his refusal to give himself the one luxury in life he truly desires (a 1967 yellow-and-black GTO)—reflects this personal and political identity.

The success formula he has used to get ahead is different from that of most modern politicians. Unlike Ann Richards or fellow Aggies Phil Gramm and Henry Cisneros, Sharp doesn’t have a strong ideological identity or public personality. He doesn’t give a particularly good speech; nor does he make a flashy impression on TV. He doesn’t look like a guy who has spent much time in New York or Washington or, for that matter, Houston or Dallas. At 43, he has worked his way up the political ladder—as legislator, state senator, railroad commissioner, state comptroller—mainly by using insider skills. Now he is a national figure, the person Bill Clinton used to distance himself from the Democrats’ tax-and-spend reputation.

Last September, when Vice President Al Gore appeared on David Letterman’s show to complain about how bureaucrats do nutty tests such as breaking pricey ashtrays and then counting the number of shards, he cited Sharp as his model for eliminating government waste. In November Sharp traveled to Great Britain to lecture members of Parliament on getting the fat out of government bureaucracy.

Yet the unanswered question about John Sharp is, Is his budget cutting for real? The short answer is that no one knows for sure except Sharp, because he controls all the numbers about how much money comes in to the state treasury and how much goes out, including the estimates of how much he has saved. However, this much is true: Everybody—even his enemies—believes he has saved the state something. At a minimum, Sharp’s budget cutting is brilliant political marketing. When his first audit, “Breaking the Mold,” was released, the press rushed to heap praise on Sharp, reporting that his plan would save $2 billion, maybe $4 billion, maybe even $6 billion, and save us as well from the dreaded income tax. He has taken the theme of reinventing government and used it to invent his own success.

On a cold, gray December day, Sharp climbed into the copilot seat of an aging Beechcraft Baron, and soon we were up and flying in brisk winds, headed for a day of speech making in his native South Texas. I was sitting behind the pilot of a six-seater. Flying with someone who has made his reputation on being a cheapskate can be unsettling. The cabin was unpressurized and noisy, and the upholstery on the seats was shredded.

“Have you heard of my Diet Coke theory of politics?” Sharp yelled over the roar of the airplane’s engines. The theory is, The fewer the number of Diet Coke drinkers in a crowd at a political fundraiser, the more likely it is that the people in the room represent the majority of Texans. “Years ago I noticed that if I went to a fundraiser in Austin where there were a whole lot of lobbyists and people with influence, everybody was drinking Diet Cokes,” shouted Sharp. “But if I went to a fundraiser in a midsize or small Texas town where nobody gave a damn about politics, there was always plenty of Diet Coke left at the end of the evening.” The lesson is that most politicians listen to the Diet Coke–drinking insiders, whose views are often at odds with what ordinary people want from government.

Sharp drinks regular Coke and feels closer to the non–Diet Coke drinkers. To him, the Diet Coke crowd is not only the political in crowd but also, by extension, sophisticated urban Texans, and Sharp realizes that they are not his constituency. By almost any conventional standard, Sharp is thoroughly out of step with modern politics. He is a rural Catholic politician in an urban Protestant state. He is a conservative in a Democratic party that has been taken over by liberals. He is cheap in an age of consumerism. If you saw Sharp walking down the street, you would never figure him for a politician. He has only maroon ties. On his South Texas trip, he wore one with a plain blue suit, a white shirt, and a pair of resoled loafers.

Sharp believes that most politicians listen to the Diet Coke–drinking insiders, whose views are often at odds with those of ordinary people.

Sharp has used the concept of reinventing government to get himself back in the political mainstream. It is a classic conservative Democratic belief—not an anti-government philosophy along the line of Phil Gramm’s, but not exactly pro-government either. He is betting that the public will accept government spending if someone assures them that their tax dollars aren’t being wasted. Of course, that someone is John Sharp. On this particular day, he spoke at noon to about one hundred members of the Harlingen Rotary Club. As Sharp stood behind the podium, fingering his tie and watching his audience eat turkey and dressing, his demeanor was that of a common-sense, anxious-to-please Aggie. His whole speech was aimed at promoting a conservative Democratic message, although he never said that in so many words. Instead, he attacked both Republicans and Democrats and held himself up as something apart from either. “The difference between Democrats and Republicans,” he told the Rotarians, using one of his favorite lines, “is that both of them will spend every damn dime in the Treasury, but the Republicans will tell you they feel bad about it. ”

He knew how to provoke an emotional response from the Rotarians. “Food stamps,” he sneered, employing a phrase that reeks of government mismanagement. “Now, it’s hard to find a worse-run system than food stamps, even in government.” First, Sharp said, trees are chopped down to make paper, then the paper is sent to New York, where the stamps are manufactured, then they are sent to Omaha for sorting, and finally they are given over to the U.S. Postal Service, “where,” Sharp said, pausing for drama, “lots and lots of them are stolen.”

He then announced his own better idea. In a planned pilot program in the Houston area, people eligible for food stamps will be issued electronic cards to be used like Pulse or other automatic teller bank cards. The hope is to cut down on manufacturing and transportation costs as well as theft. If the system works, it will be put in place statewide. One advantage is that the cards can be used to buy only items that are allowed under government regulations. “Why put up with all this fraud?” asked Sharp. “We’ve got the technology to do it a better way.”

His solution to the food stamp mess illustrates the way Sharp approaches problems: First, he looks for something government does that drives taxpayers crazy, and then he looks for a modern technological solution to solve it. Sharp is a throwback to the era when conservative Democrats governed Texas—the thirty years following World War II, a period that produced Lyndon Johnson, John Connally, Lloyd Bentsen, and Bill Hobby. The conservative Democrats prospered by putting the state’s business climate ahead of spending and regulatory issues such as welfare and the environment. They were different from Republicans because they would address social problems when the clamor from liberals began to win support from the public, but even then their rhetoric remained conservative—just as Sharp’s does. In effect, they stayed one step ahead of the public posse.

Sharp and Ann Richards are great friends who talk frequently, but they are different in one respect: Richards will move only as far as she thinks the public will accept; Sharp, like conservative Democrats of the past, moves only as far as the public forces him to. His handling of the Texas lottery was characteristic. Sharp is personally opposed to gambling of all kinds, but when voters approved the lottery in 1991, he stepped forward as comptroller to garner as much attention as possible. He regularly posed for newspaper photographs and TV sound bites with his arm around lottery winners, and he kept his budget down by contracting out much of the work, holding the start-up staff to only 186 employees (compared with more than 1,000 in California and 775 in Florida).

After the Harlingen speech, Sharp went to Corpus Christi for an appearance at a higher education conference and a fundraiser. Everywhere he went, people asked not whether he will run for governor but when. Sharp was always noncommittal. Privately he told me, “The worst thing a politician can do is telegraph his punch. Ben Barnes”—a conservative Democrat heir apparent of the early seventies who never made it— “always seemed like he was running for governor.”

At the evening fundraiser in a bayfront high rise, Sharp was surrounded by the kind of people who have been with him ever since he got his start in politics: prominent South Texas conservative Democrats who regard Sharp as a port of reentry to the Democratic party. Midway through the event, Lucien Flournoy, a South Texas independent oilman, cornered the state comptroller and told him, “I predict you’ll be governor right after Ann or [GOP candidate George W.] Bush.”

Then a look of doubt crossed Flournoy’s face, and he began to paint the past in nostalgic pastels. “Things aren’t like they used to be,” he told Sharp. “In the old days, the forty-five counties down here in South Texas were so united we could pretty much determine who’d be the next governor.” Sharp nodded and replied in a quiet voice, “Not anymore.”

From the front porch of the three-bedroom ranch-style brick Sharp family home near Victoria, it is possible to see reminders of the kind of wealth that once held sway in South Texas. The horizon is dotted with a large grain silo, pump jacks, and a few head of cattle. This was once the land of great agricultural and oil empires. In the 1850’s, Tom O’Connor owned a 500,000-acre ranch near here. Sharp’s father, who worked for Mobil Oil for 38 years, once supervised a crew that pumped 46,000 barrels of oil a day off an 11,000-acre ranch.

The Sharp house is fourteen miles to the south of Victoria in little Placedo, a town with a brown-tiled post office, a fire station, a combination cafe and grocery store, and an elementary school. Anglos are a minority here; around 65 percent of the population of 515 is Mexican American. It’s not difficult to understand why anyone from Placedo, even someone who grew up solidly middle-class like Sharp, would think of himself as an outsider in urban Texas.

“I love Placedo so much,” he says. “If I had my druthers, I’d still live there and fly back to Austin every day to go to work.” We were seated in his office just east of the Capitol. Unlike most politicians, whose offices are filled with photographs of themselves standing arm in arm with more-important politicians, Sharp decorates his walls with photographs of himself on expeditions with his hunting buddies. The office fits Sharp’s rather austere personality. He has a strong self-deprecating streak, which revealed itself during our interview in his resistance to self-analysis at every turn and in his constant focus on how regular and ordinary he is. When I asked what he considers to be his primary rule of politics, he replied without hesitation, “Personalize everything. When a problem crosses this desk, I try to think how someone I know, either a friend from Placedo or a relative, would be affected by it, and then I do what’s best for them.”

Sharp’s jokes are self-deprecating as well. Not much time passes between quips in a conversation with him. He is funnier in person than in print because of his facial expressions and sense of timing. “My first race for office was for president of the seventh grade,” Sharp told me, when I asked how he got interested in politics. “I won by one vote. I felt it was a disgrace to vote for myself, so I voted for my friend, and my friend told me he voted for me.” Then he added, “I think he lied.” Sharp laughed at his own joke, but hidden in the punch line is what Sharp usually cloaks: his ambition.

He inherited the ambition from his mother, the granddaughter of Czech immigrants. Venus Marek was a rebel; when she married M. L. Sharp, she rejected her mother’s demand that she stay home, help on the farm, and rear her family as part of the larger clan. Instead, Venus went to college, taught school for 33 years, and joined the theologically liberal Unitarian Church. But her son John was no rebel. When I asked him why he converted to Catholicism shortly before he married Charlotte, he brushed off his religious upbringing by saying, “Unitarians are big thinkers.”

If the first major influence on his life was growing up in modest circumstances surrounded by great wealth, the second was attending Texas A&M. When Sharp arrived in College Station in 1969, the campus of 15,000 students was splintered politically over the Vietnam War and the students-versus-administration issues that were dividing campuses everywhere. The corps of cadets had always dominated campus politics, but the dissension opened the door to a challenge. Sharp was a member of the corps, and he supported the war. But he sided with the dissidents on the campus issues that involved a stronger voice for students. The competition was intense, mainly because Aggies are intense. One way to look at modern Texas politics is as an extension of the Aggie melodrama that began in the late sixties and created an entire generation of Texas politicians: agriculture commissioner Rick Perry (Sharp’s college roommate), land commissioner Garry Mauro, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Henry Cisneros, Congressman Chet Edwards, and Kent Caperton, who was the acknowledged leader of the state Senate in the eighties.

“I’ve never seen anything rougher than student-body politics at A&M,” Sharp told me. As a sophomore, he won election for class president as part of a coalition Caperton had forged of dissidents from every campus faction, including the corps. Sharp was notorious for plastering the campus with signs that said “Got a problem? Call John Sharp.” Around campus he was known for his uniquely Aggie sense of humor. He shaved not only his head as part of his initiation into the corps but occasionally other parts of his anatomy as well. “Sharp was always doing practical jokes,” says Caperton. “Besides, he could throw up at will.”

Aggies appreciate such talents. Rick Perry tells a story about a Friday night when he and Sharp had gone out to drink beer. They were standing on a street corner when a ferocious-looking hippie roared through town on a motorcycle. The hippie decided to engage the Aggies in a game of chicken. Sharp crouched to the ground and pawed it like a bull. As the hippie drove closer, Sharp reached down to the ground, grabbed a handful of crickets, and popped them in his mouth. The hippie screeched to a halt, staring at the cricket juice running down from Sharp’s mouth. He turned his cycle around and roared off, beaten. “And that,” recalls Perry, with a kind of good-ol’-boy pride you find only in Aggies, “is the night I realized that John Sharp has serious moxie.”

On his climb up the political ladder, Sharp has had his differences with his fellow Aggies—he and Mauro are rivals, and his friendship with Perry was strained by Perry’s switch to the Republican party—but Sharp’s sense of humor has saved several friendships. In 1980, when Caperton ran for the Senate from the district that includes College Station, Sharp, then a member of the Legislature, supported Caperton’s opponent, a longtime incumbent conservative Democrat named Bill Moore. “You can’t win,” Sharp told Caperton. “In fact, if you win, I’ll kiss your ass on Main Street.” After Caperton won the election, Sharp telephoned again. “I won’t kiss your ass,” said a penitent Sharp, “but I will get right close to the small of your back. ”

As John Sharp tells it, he discovered the power of the comptroller’s office while he was a student at A&M. One day he was flipping through the Texas Almanac and came upon an entry that read “Robert Calvert, state comptroller.” “Who the hell is Robert Calvert?” Sharp thought to himself. “One of these days someone is going to take this job and really do something with it.” As it happened, Bob Bullock figured out the same thing and got elected comptroller in 1974, sixteen years before Sharp did. But Sharp has given the office a prominence even Bullock was not able to.

After graduating from college in 1973, Sharp took a job as a budget examiner for the Legislative Budget Board, where he learned how the state budget is put together. Five years later, he and Charlotte married and moved to Victoria, where he opened a real estate business. Almost immediately the local state legislator ran for Congress, leaving the seat vacant. Sharp ran unopposed, largely because of the strength of ties he had already established with the local power structure; while still in high school, for example, he had gotten to know Zac Lentz, the local fundraiser and political operative for conservative Democrats. Two years later, the state senator for Sharp’s area died. In the special election to fill the seat, Sharp faced Tim Von Dohlen, a veteran legislator from Goliad. To appeal to Mexican Americans, he took an immersion course in Spanish at the University of Houston. His primary tactic, however, was to position himself as the true conservative in the race. This was not an easy position to take, since Von Dohlen had led fights against drug use and abortion. But Sharp’s supporters seized on Von Dohlen’s vote in favor of parimutuel betting on horse races. On Sundays they would go to fundamentalist church parking lots and put flyers on the windshields that said “Von Dohlen has voted for horse racing. John Sharp never has.” Sharp won with more than 64 percent of the vote.

In a talented Senate full of big ambitions and loud egos, Sharp was not one of the stars. “He was never a hug-the-microphone sort of member,” says Kent Caperton. The only legislation that brought him much public attention was his attempt in 1985 to ban the use of public funds or public facilities for abortions and a companion bill to require that minors receive parental consent before getting abortions. Sharp lost the legislative fight and came face to face with his fundamental political problem, which is that he is too conservative to be a conventional Democrat and finds Republicans too disinterested in the ordinary problems of people. “For all its limitations, the Democratic party is still rooted in the lives of average people,” Sharp said during our conversation in his office. “I could never be anything but a Democrat.”

Among Senate colleagues, he earned respect by being a smooth inside operator. In 1985, when Bob Lanier, now the mayor of Houston, was chairman of the Texas Highway Commission, Sharp asked Lanier to build a highway interchange near his parents’ home in Placedo. (His father still lives there; his mother died in 1985.) At first Lanier was reluctant, but Sharp told him, “If you build this interchange, you’ll own my vote for as long as I’m in the Senate.” Lanier never got to cash in his chips; 48 hours after the deal was official, Sharp announced his candidacy for a seat on the Texas Railroad Commission. With the backing of conservative Democratic money raisers, Sharp won the Democratic primary without a runoff and defeated a Republican with 55 percent of the vote. It didn’t take long for Sharp to make a reputation for himself by breaking a long-standing deadlock over trucking regulation, which is overseen by the Railroad Commission. He did that in classic conservative style, by using insider politics—and his friends—to accomplish a little deregulation and make it seem like a lot. In this case, the friend was Bill Messer, a legislative colleague turned Austin lobbyist who represented Central Freight Lines. Sharp had won the seat with the financial backing of the regulated trucking industry, but he immediately told Messer that the industry had to move toward deregulation. “The public wants deregulation,” Sharp told Messer. “You can accept a little now or a lot in two years.” Messer knew that Sharp’s political instincts were correct. Together they sat down and worked out a compromise. Messer won continued protection for the trucking industry, and Sharp won increased competition. “To be good at politics, you have to enjoy it,” says Messer, “and no one enjoys it as much as Sharp.”

As soon as Sharp became a statewide official, he started talking to friends about running for state comptroller. When Bob Bullock decided to run for lieutenant governor in 1990, Sharp jumped into the race. He had no major opponent, so he invented one. Other politicians and Austin insiders were focused on solving the school-finance crisis, but Sharp’s instincts told him that most voters didn’t really care about the complicated issue, and polls backed him up. What voters cared about was finding out how their school taxes were being spent. In a TV spot, Sharp vowed to audit school districts and said, glaring at the camera, “and if the bureaucrats don’t like it, they’re outta here.” The era of the comptroller’s office as massive publicity machine, with power to audit all state agencies, all schools, every prison, even the books of financially troubled hospital emergency rooms, had begun.

The first bill Ann Richards signed as governor in 1991 was Senate Bill 111, which gave Sharp his power to audit every nook and cranny of state government. At the time, Texas faced a budget shortfall of billions of dollars. Richards had just won a shaky election as governor. Bullock wanted an income tax, but he also wanted to assure voters that every dollar had been squeezed out of the budget first. They turned to Sharp, who immediately seized the possibilities. He took the vast amount of information the comptroller has available concerning the finances of state government and created an aura of mystery about the audit process. First of all, he stealthily guarded how the audit was being put together. He erected a wall of secrecy to prevent leaks. Only four people—Sharp and his top three aides—knew how the whole audit was shaping up.

The secrecy was fundamental to the alchemy of the audit. The image he created of himself was one of white knight, and the Legislature, hemmed in by a constitutional requirement to balance the budget, accepted it. No one understood what was going on better than Bullock, now lieutenant governor and leader of the Senate. He tried without success to find out Sharp’s plan with the audit and was furious when he couldn’t. Neither could reporters. Next came a series of well-calculated leaks from the comptroller’s office. First came rumors that the audit would save the state hundreds of millions of dollars, then a billion, then two. Finally, as a special legislative budget session drew near, Sharp grandly presented “Breaking the Mold.” The audit had 193 recommendations that, if adopted by the Legislature, would save enough money—an astonishing $4.5 billion—to stave off a tax increase. An estimated 50 to 75 percent of the so-called savings were proposals that various budgetary committees already knew about, but Sharp’s genius was in pulling them all together and marketing them as a package. The audit framed the entire debate: One by one, bills were passed until $2.1 billion worth of changes had been made, enough to prevent a major tax increase, although not enough to prevent a lot of minor ones.

The audit is what made Sharp a star. But skeptics wonder whether it produced any real savings. Kay Bailey Hutchison, who served as state treasurer before winning the U.S. Senate seat last spring, calls Sharp’s audits “accounting tricks.” During her campaign, she went to Sharp’s home turf in Victoria and told his hometown newspaper that of the $4.5 billion adjustment Sharp claims to have made in the budget, only a paltry $13 million are actual cuts in spending. The rest she dismissed as “smoke and mirrors.” A more independent analysis, compiled by Ohio-based State Policy Research, says that 6 percent, roughly $300 million, of the $4.5 billion are real spending cuts. (Sharp himself puts the “real” cuts at closer to $1 billion.) The largest single “savings” came from Sharp’s plan to transfer $1 billion of the state’s cost of the Medicaid program to the federal government—not a true cut, but a huge savings to Texas taxpayers nevertheless. Another way he closed the budget gap was by onetime shifts in revenue; for instance, he recommended delaying an end-of-the-year payment to the teachers’ retirement system of $234 million by one day in order to carry it over to the next budget cycle.

When Clinton put Vice President Al Gore in charge of the national audit, Sharp’s deputy comptroller, Billy Hamilton, went to Washington and helped organize the work teams. The result looked a lot like Sharp’s audit in Texas, even down to the packaging. It came in a red, white, and blue cover and was titled “From Red Tape to Results.” The Clinton administration claims that if the proposals are adopted as law, $6 billion could be saved through 1998. But the Congressional Budget Office estimates the savings would be only 5 percent of what Clinton claims, or $300 million—not much more than pocket change in Washington.

Sharp contends that it is shortsighted to look at the Texas audit from the point of view only of bottom-line savings. “We aren’t just trying to cut programs so we can save money in the Treasury,” he said. “What we’re trying to do is make government function like an efficient business.” This has been said before, many times, in Washington and in Austin, with little evidence of success. Still, with Sharp offering the carrot of millions of dollars in savings, the Legislature consolidated a number of state agencies; in one case, fifteen agencies concerned with environmental and natural resource programs were combined at a “savings”—or so Sharp estimated—of $6 million a year.

Sharp does run his own office like a business; he oversees policy like a CEO and delegates the details. Deputy comptroller Billy Hamilton runs the weekly meetings of division managers. Most of the time Sharp doesn’t even attend. Many of his ideas come from Hamilton. When Hamilton went to get a new driver’s license in 1991, he had his photograph taken and was told he would receive the license in the mail in six weeks. That same night Hamilton went to a Blockbuster video store and was immediately issued a new card. Ever since then, Hamilton and Sharp have tried without success to institute on-the-spot issuing of driver’s licenses.

Sharp’s rise has inspired some jealousies and rivalries, but not with Ann Richards. He is her closest ally in state government. It was Richards who in late January asked Sharp to look for extra beds in Texas prisons so the state could stay in compliance with a federal court order on prison population. Richards also, according to Sharp, offered to appoint him to Lloyd Bentsen’s Senate seat last year, but, he says, he turned down the job. “I realized I didn’t want to move to Washington,” he told me. “I don’t want to do what those guys do every day. If I went there, it would be to try to figure out how to slow everything down and blow up what they do.” Sharp also says he had doubts about whether a Democrat could win the race. His own chances would have been diminished by his anti-abortion stance as a legislator; women activists opposed his appointment, even though he has modified his position on abortion. “If you live in a democracy, you have to live by the will of the many,” he said. “When I was in the state Senate, a majority of my constituents were opposed to abortion. If I’d run for the U.S. Senate, a majority of my constituents would be in favor of it. The other reason I shifted my position is I don’t like abortion, but I don’t think you can legislate it out of existence as long as women can take a bus and go where it’s legal.”

At the moment, Sharp faces an unexpected fight for reelection before he can think about his next office. On January 3, the last day of filing for the March 8 primaries, Teresa Doggett, a black Republican from Austin, entered the race for comptroller. Doggett had planned to run for state treasurer. After deciding that the real power wasn’t in the Treasury job, she decided to run for comptroller instead. Teresa Doggett is a political unknown (her husband, John, is a lawyer who testified against Anita Hill in Clarence Thomas’ confirmation hearings), but her candidacy does take aim at Sharp’s vulnerability: She’s a mainstream Republican woman, and these days the line between mainstream Republicans and conservative Democrats is extremely thin.

Ultimately the question that will decide John Sharp’s future is not whether his audits of governmnent measure up to their hoopla but whether enough average voters are offended by political extremes to beat a path back to the center. In other words, Is there room in Texas politics for a conservative Democrat? John Sharp is betting that he has the secret. “The way I stay alive politically is that I fill vacuums,” Sharp said.“I figure if I stir up enough controversy, everybody will forget they’re mad at one another and start trying to fix things.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- John Sharp

- South Texas