The judge’s legal filing began with an Elvis Presley quote: “Truth is like the sun; You can shut it out for a time, but it ain’t going away.” It only got weirder from there.

In his seven-page order laying down some ground rules for attorneys representing HouseCanary Inc. and Quicken Loans Inc. in a hard-fought federal lawsuit involving alleged stolen trade secrets and fraud, San Antonio’s U.S. District Judge Fred Biery dropped some impressive pop-culture refs (Rambo! Sgt. Joe Friday from Dragnet! Star Wars!), bemoaned the migration of Yankee attorneys into Texas, and gave a brief history of time. (Credit to the San Antonio Express-News for being the first to report on this bizarre order.)

Arguably the oddest nugget in the order is Biery’s threat to punish the attorneys if they don’t behave with proper courtroom decorum. “Although the Court expects vigorous advocacy and does not expect counsel to hold hands and sing Kumbaya,” Biery writes, “the consequences of unprofessional conduct or acerbic shrillness in the pleadings can also include revocation of pro hac vice privileges, sitting in timeout in the rotunda of the courthouse and opposing counsel kissing each other on the lips in front of the Alamo with cameras present.” Apparently he’s made that last threat before—Biery noted that previous attorneys quickly straightened out after he raised the public makeout sesh as potential punishment. “As did Sergeant Joe Friday, the Court expects ‘Just the facts, ma’am,'” Biery wrote to close the paragraph.

According to the Express-News, Biery is known for his unique brand of legalese (his ruling in a case involving San Antonio strip clubs is required reading), but this order seems to be his magnum opus. It just covers so much ground. “There will be no Rambo tactics or other forms of elementary school behavior,” he writes on page two. “Simply put: Do not play games.” Biery makes known his preference for analog over digital, urging both parties to “make time for earspace, i.e. talking and listening as opposed to texting and emailing.” On page three, when addressing the potential of appointing a special master, Biery calls the potential appointee a “curious amigo” (a punny translation, perhaps, of amicus curiae). He also cites “The Unauthorized but True Story of Dragnet and the Films of Jack Webb.”

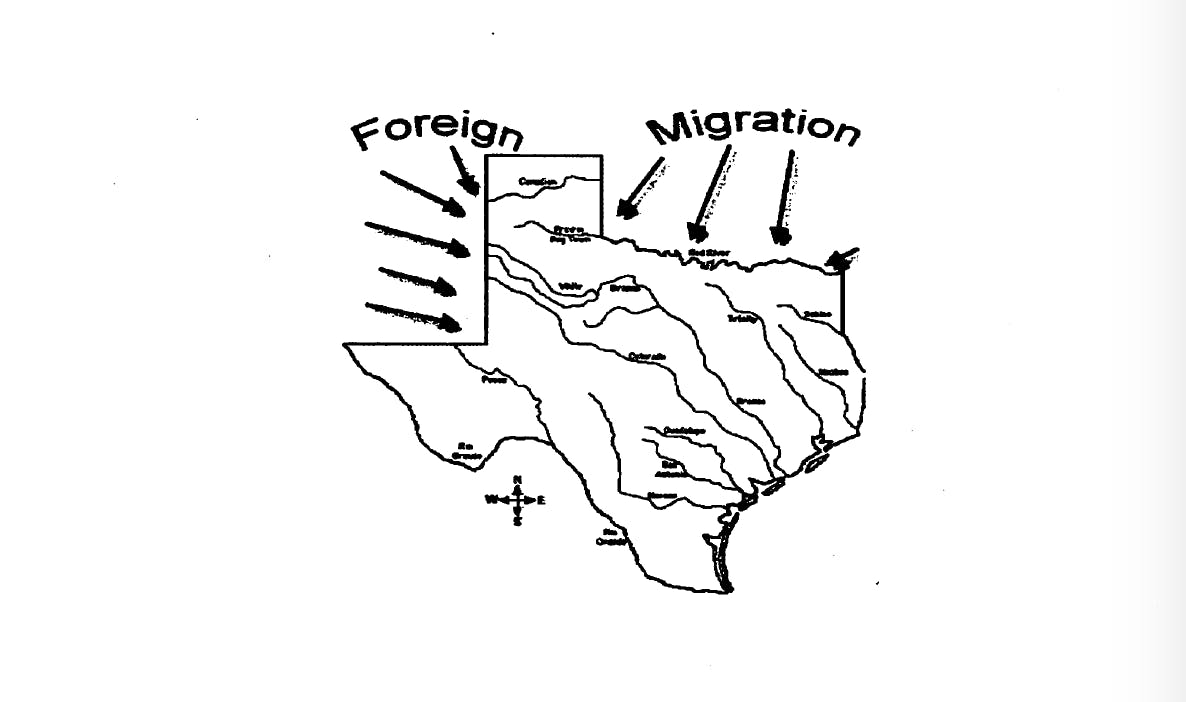

Later, Biery gets nostalgic for the good old days. “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, the San Antonio litigation community consisted of about 300 lawyers who knew each other on a professional and social level, some of whom are quite capable of trying these kinds of cases and whose handshake agreements were kept, making court orders often unnecessary,” Biery writes. “For reasons known only to the parties who pay the bills, the more recent phenomenon is for equally capable counsel to immigrate into Texas as shown in this illustration:

As another old school San Antonio lawyer, Hobart Husan Jr., was fond of saying, ‘Texans, you are guarding the wrong river.'”

Of course, Texas judges have issued plenty of artful legal orders before Biery’s latest. Texas Supreme Court Justice Debra Lehrmann once quoted Walter Sobchak from The Big Lebowski in a decision (“For your information, the Supreme Court has roundly rejected prior restraint”). In 1996, U.S. District Judge Samuel B. Kent lambasted Big Insurance attorneys from Philadelphia after they requested a federal case be transferred from Galveston to Houston because it was too far from the nearest big-city airport. “This court certainly does not wish to encumber any litigant with such an onerous burden,” Kent wrote in his denial of the transfer. “Defendant should be assured that it is not embarking on a three-week-long trip via covered wagons when it travels to Galveston. Rather, defendant will be pleased to discover that the highway is paved and lighted all the way… and thanks to the efforts of this Court’s predecessor, Judge Roy Bean, the trip should be free of rustlers, hooligans or vicious varmints of unsavory kind.” Former state District Judge Ted Poe—now a U.S. congressman—was perhaps known best for implementing oddball sentences, including ordering a convicted child molester to put up a sign in his front yard reading: “No children under the age of 18 allowed on these premises by court order,” and making shoplifters post up outside the stores from which they had stolen, holding signs about their crimes.

But none of those other judges’ orders capture the same meandering bizarreness of Biery’s most recent masterpiece. In the final section of the order, titled “Keeping Things in Perspective,” Biery contemplates the bigger picture. “Condensing 14 billion years into a twenty-four hour time line reveals that our ancestors showed up at about a minute before midnight, which means that our biblical three score and ten and the time of this litigation is a nanosecond blink of an eye.” Whoa. Deep. “Accordingly, may we move toward a reasonable conclusion with or without a trial whether in this Court or some other.” For reference, Biery includes an image depicting the history of the earth as a 24-hour clock, adapted form Carl Sagan’s Cosmic Calendar.

Biery returns to the tangible world in Appendix A, in which he breaks down “The Rule: Treat others (including lawyers, parties, witnesses and Court staff) as you would like to be treated.” The penalties for “not abiding by The Rule” include “loss of respect” from colleagues, “the writing of The Rule in multiples of fifty on a Big Chief tablet with a Number Two pencil”—this punishment, Biery writes, “is reserved for those whose conduct is particularly childish”—and “The donation of numerous pictures of George Washington to deserving charitable organizations.”

Biery closes his order as every judge should: with a photo of Abraham Lincoln, accompanied by a quote in which Honest Abe reminds all lawyers to put goodness over business. It seems likely the warring attorneys in the case over which Biery is currently presiding will follow suit—otherwise, we may soon see some PG-13-rated action outside the Alamo.