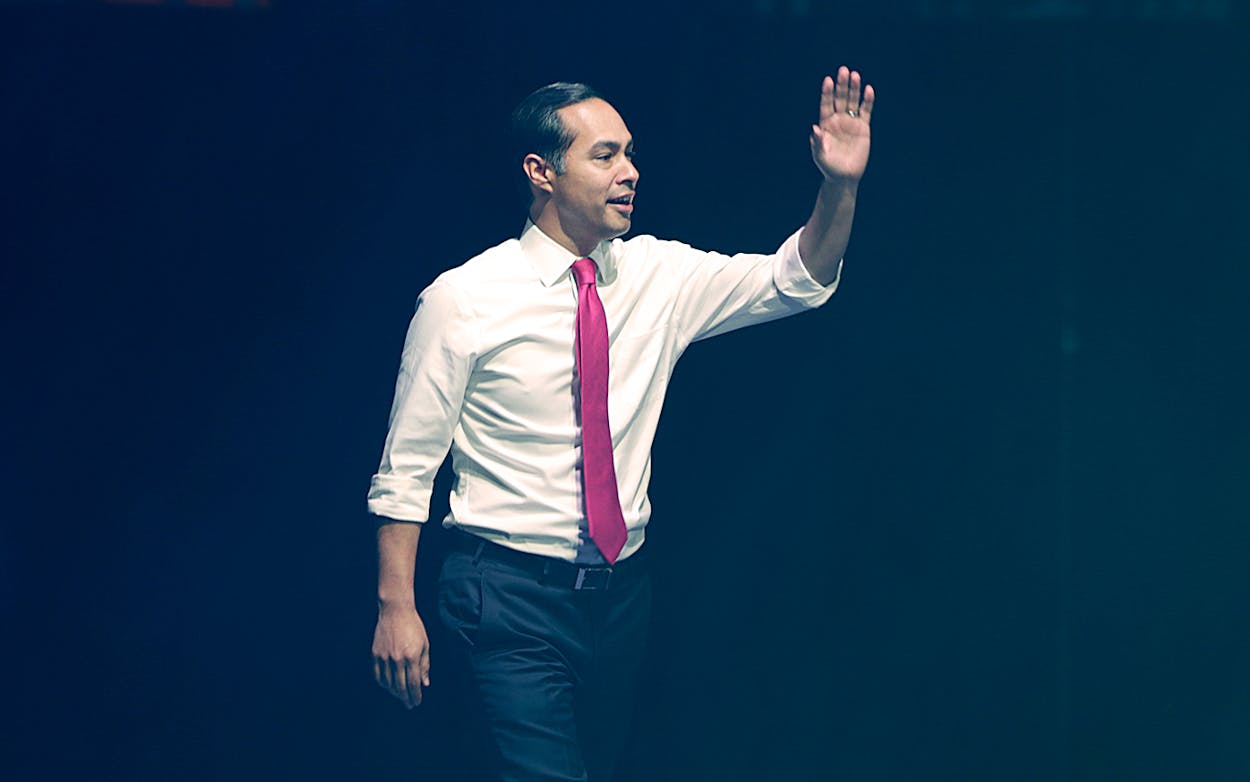

They say that the two happiest days of a boat owner’s life are the day the boat is bought and the day the boat is sold. So it is, maybe, for second-tier (third-tier?) presidential candidates. Julián Castro’s abrupt departure from the race prompted a wave of praise and speech-making about his willingness to stand for his ideas and the great tragedy of his disappearance, a strange ritual that also followed the departures of Kamala Harris, Jay Inslee, Beto O’Rourke, and others, in varying forms and fashions. Once candidates are no longer a threat, they’re suddenly beloved.

Castro is not the first Hispanic candidate to vie for a major party presidential nomination. That would be Ben Fernandez, who won three delegates at the Republican National Convention in 1980. Nor is he the first Democrat: that would be former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson, in 2008. Nor did he get the closest to the nomination: that’s Ted Cruz, in 2016. But the encomiums are right, in a sense. Castro’s campaign was a moment of sorts, even though it never really got off the ground. More so than Richardson’s run, Castro’s campaign felt like a predecessor of future Latino presidential bids. His run also came at a critical moment in American history.

Immigration is the central issue of the Trump era. Trump was elected on his hostility to immigrants, and the question of how to treat migrants has been the central moral and political question of his first term. Far beyond the family separation stuff, America is inflicting great harm on migrants and refugees here and in Mexico. But at the start of the primary season, it was not central to the Democratic debate. Even though Americans in polls express more openness to immigration and extending legal status to the undocumented than ever before, Dems fear, perhaps rightly, the politics of the matter. Xenophobia is a stronger motivator for voters than its opposite, especially in the places Democrats most need to win next year.

Castro centered the issue, and pushed other candidates to talk about it. Perhaps his strongest moment in the campaign came in the first debate, when he kneecapped O’Rourke in a scuffle over a relatively obscure section of the U.S. criminal code that makes unauthorized entry into the U.S. a prosecutable crime. Castro was right on the merits—the clause isn’t necessary to “secure” the border and is the cause of a great deal of suffering.

To a lot of people not familiar with the intricacies of immigration law, Castro’s call to eliminate the illegal entry statute sounded like “open borders,” which made it all the more remarkable that he was willing to go there, and that other candidates fell in line. We’ll see how that plays out in November. For now, give Castro credit: without him, it seems likely there would have been even less discussion in the primaries of the most important subject in American political life.

It’s not the only thing Castro spotlighted. In a eulogy for Esquire, Charles Pierce wrote that Castro was “a righteous voice in this campaign for people whose voices are truly silent.” He “campaigned in soup kitchens, and in homeless shelters, and in small urban gardens, where the truly voiceless try to get from sunrise to sunset holding desperation at bay with a charity toothbrush and growing their own vegetables.” More:

He campaigned for the minority citizen whose guts clench when they see the red flashing lights of the squad car behind them on a dark road late at night, and for the teenager who has to worry about how fast he takes his hands out of his pockets. He spoke their names on the national stage—Philando Castile, Michael Brown, Laquon McDonald, Sandra Bland, and the others—like a sad litany out of a cathedral history. He dared us to say the names, too.

This vision of Castro as Tom Joad—whenever there was a Jefferson-Jackson Dinner in Cedar Rapids, he’d be there—might ring a little odd to Texans who remember Castro as a well-regarded but pretty bog-standard Texas mayor—a pro-business moderate who courted support from police unions—and a Housing and Urban Development secretary with a mixed record. But circumstances make the man, and Castro did effect a remarkable transformation on the campaign trail. (It didn’t always go smoothly—on the right, he’s now mainly famous as the guy who staked out the position that trans women deserve free abortions, later clarifying he meant trans men.)

Pierce also writes that Castro’s departure “should make the country melancholy about how we do politics in the age of big money.” Castro’s voice was valuable, and he’s been pushed out at a time when the Democratic primary has expanded to include two weirdo billionaires who are buying their way into the process. And the fact that Tom Steyer and Mike Bloomberg are in the running now is a travesty: it’s an insult to the democratic process. And it’s unfortunate for the increasingly diverse Democratic party that their presidential field is narrowing down to two old white guys, a slightly less-old white woman, and the kid from Mad magazine.

Castro made headlines by pointing to the first two states in the primary, Iowa and New Hampshire. They were unrepresentative of the country at large, he said, too white. Granted, those states were chosen because they’re small and allow underdog candidates to win by campaigning hard, like Barack Obama did in 2008. And the two taken together with Nevada and South Carolina, the next two states, look a lot more like America. But, still, he’s right.

But it’s also unlikely that Castro would have done better if the first Democratic contests were in Hispanic-heavy Nevada, or African American-heavy South Carolina. By and large, nonwhite Democrats have clung to the two old white guys, Biden and Bernie, much the same as white Democrats. (A Telemundo poll in November had Castro in a three-way tie for fourth place with Hispanic voters at 2 percent.)

What’s next for Castro? Well, home for now. As early as November, he was trying to patch things up with O’Rourke, who’s now the most prominent Texas Democrat and will remain politically active in the future. In the last six months, it’s been hard to shake the feeling that Castro was running for vice president. The conventional wisdom about the Democratic primary is that the winner will want to gender-balance the ticket. If that’s true, Castro would make a good running mate for Warren, possibly, but her star has faded a bit, and he’d make a poor fit with the other front-runners. (It’s perhaps noticeable that the two candidates with whom Castro sparred with the most, Biden and Beto, are both of the male persuasion.)

As for the Democrats: while it’s perhaps unfortunate that only white candidates are in the top tier of the presidential race, the party has a much bigger problem. Democrats have a decidedly thin nonwhite candidate bench above the level of mayoralties and state legislatures. African Americans are a key constituency of the Democratic party, for example, but it has only two African American senators—and both ran for president this year. There are currently no African American governors and only one Democratic Hispanic governor.

There are a variety of reasons for this diversity problem, some out of the hands of Democrats. Even in states where Hispanic voters have a degree of political power, they run into significant obstacles when seeking higher office. In Texas, for example, there are plenty of ambitious Hispanic lawmakers in the Legislature who have nowhere to go—winning a statewide race is just too daunting. In Arizona, white moderates like Kyrsten Sinema win elections. In California, president pro tempore of the state Senate Kevin de León took a shot at unseating entrenched Senator Diane Feinstein and ran headfirst into a brick wall. The pathways for Democrats to incubate Hispanic political talent are overgrown with weeds.

If for no other reason, you haven’t seen the last of Julián Castro. (Or his twin, Joaquin, for that matter.) May we suggest a trip to Big Bend with the equally unemployed Mr. O’Rourke to clear your head and clear the air, Mr. Castro? Just don’t turn your back.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Julian Castro