For years, the tantalizing prospect of Texas becoming a “purple” battleground state has motivated Democrats—who have had their hopes dashed in election after election. However, the 2018 midterms showed cracks in the GOP’s hold on the state, with Democrats picking up congressional seats in districts that were drawn by Republican mapmakers to be easy holds. Now polling suggests that 2020 could see further gains by Democrats.

While all eyes are on the presidential campaign, and, er, some eyes are on the surprisingly low-profile Senate race between GOP incumbent John Cornyn and Democratic challenger MJ Hegar, the fiercest battles in Texas are over seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Four years ago, the state had just one competitive congressional race; this year, there are a dozen races both parties are acting as if they’ve got a real shot at winning.

It’s time to get to know your swing districts. Today, we’re kicking off our “Get to Know a Swing District” series with a look at Texas’s Twenty-fifth Congressional District.

The District

History

Texas’s Twenty-fifth Congressional District was created in 1983, and for nearly thirty years it was solidly blue. After the Texas Legislature redrew the congressional map as part of a contentious and unusual mid-decade gerrymandering plan in 2003, the district earned the nickname the “fajita strip,” as it briefly stretched narrowly from East Austin several hundred miles down to the Rio Grande Valley.

In the 2011 redistricting process, the Legislature once again redrew the map, shifting the Twenty-fifth from a district based primarily in Central Texas to one that put a slice of bright blue Austin (from the city’s east and west sides, as well as parts of downtown and the University of Texas campus) together with many more voters in conservative rural and suburban areas in North Texas. U.S. representative Lloyd Doggett, a Democrat who had won in 2008 by 35 percentage points, was redistricted to the Thirty-fifth, and in 2012, Republican Roger Williams won TX-25 by 21 points. Williams sailed to easy reelections by twenty-plus points in his following two campaigns, until his 2018 challenger, Julie Oliver, cut his lead to a (still healthy) nine points—setting the two up for a 2020 rematch.

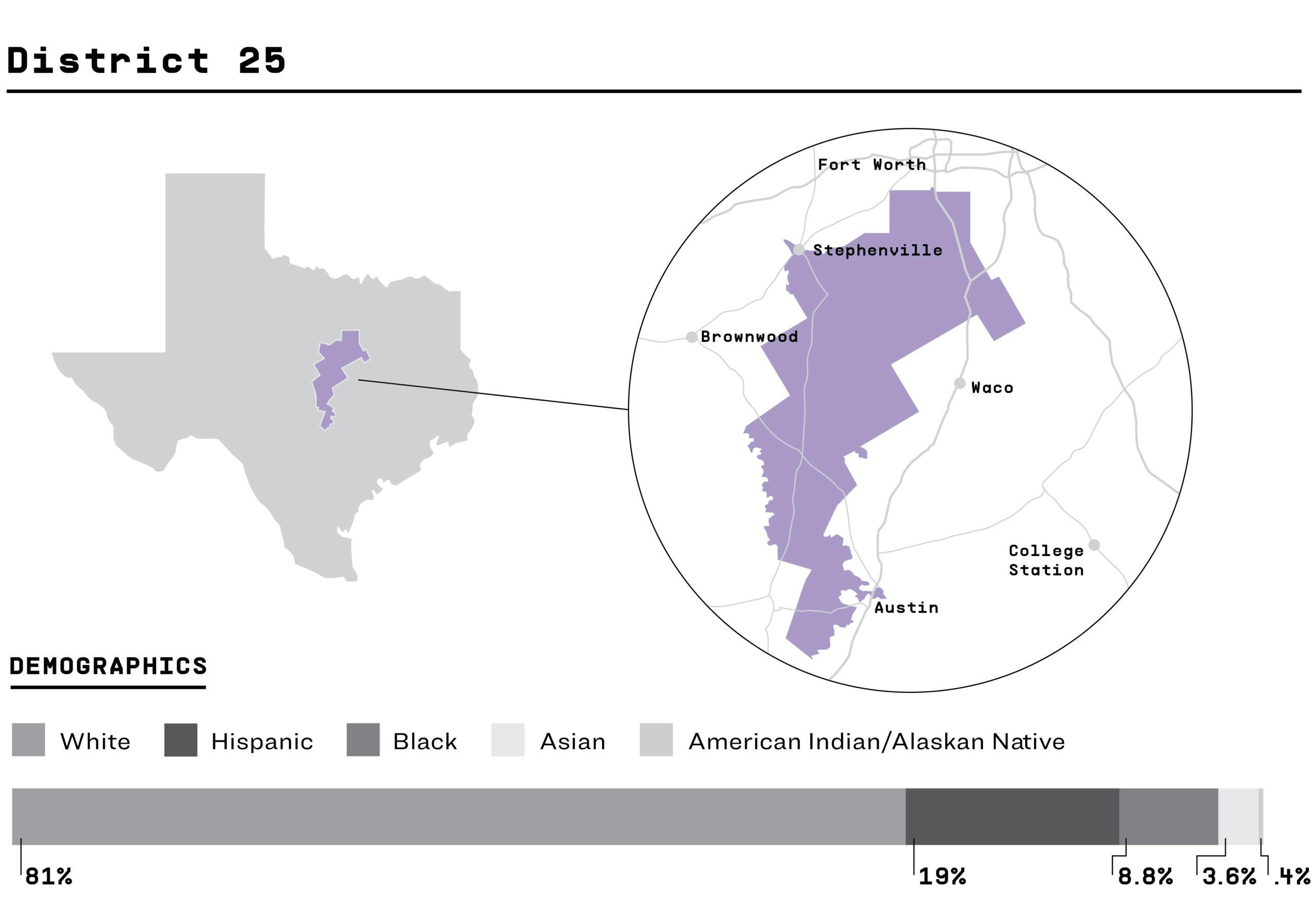

What It’s Shaped Like

A giant plume of smoke, starting from a base near San Marcos and then spreading north and growing wider as it approaches the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex. The district, which covers a long stretch of two-hundred-plus miles just west of Interstate 35, includes a disparate collection of Texans: Fort Hood falls within its boundaries, but so does Austin’s Sixth Street, as well as the small North Texas city of Glen Rose, with its famous dinosaur tracks.

The Candidates

Meet Roger Williams

A four-term incumbent, Williams, 71, is a former minor league baseball player and Texas Secretary of State. The owner of a car dealership, he was the ninth-richest member of the House as of 2018. He initially won election in 2012 on the tail end of the tea party movement, and has since become a reliable vote for Trump, siding with the president more than 94 percent of the time. Williams is a meat-and-potatoes Republican who supports gun rights and opposes tax increases. But recently his campaign has focused neither on Congress nor on Oliver, but rather on opposing the Austin City Council’s decision to cut police funding. “I think it’s a shame that Austin is heading toward being an inner city–type environment,” he told Marble Falls country radio station KBEY in August.

Williams serves on the House Committee on Financial Services. He came under scrutiny earlier this year after securing a forgivable PPP loan later revealed to be between $1 million and $2 million for his car dealership, and then voting against an act that would have required companies that received at least $2 million in federal coronavirus relief funding to disclose how much they received. He’s a well-funded candidate, with more than $1.25 million in campaign cash on hand, according to his most recent FEC disclosure.

Meet Julie Oliver

A health-care administrator from the Austin part of the district, Oliver ran for the Twenty-fifth seat in 2018, and narrowed Williams’ margin by eleven points compared with 2016—but still lost the race by more than 26,000 votes. She lives a two hour and forty-five minute drive from the district’s northern tip in Burleson.

This cycle, Oliver survived a primary against a Democratic Socialists of America–backed candidate running to her left. But her campaign itself is a progressive one: her platform includes Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, and a pathway to citizenship for undocumented residents of the U.S. She touts endorsements from big names on her party’s left, including Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Julián Castro. Through the second quarter of 2020, her campaign had a fraction of the cash on hand that Williams’s did, with just under $90,000 in the bank—though, she outraised the incumbent in the most recent quarter by a margin of nearly three to one.

The Upshot

Why It Could Flip

Trends in the Texas suburbs—especially along I-35, which the Twenty-fifth crosses in both Austin and near DFW—are good for Democrats. Three of the four Texas counties that added the most new voters since 2018—Hays, Williamson, and Travis—fall partially within the district. There are no nonpartisan polls of the race, but internal polling that the Oliver campaign released in mid-September has the challenger down by only two points, within the margin of error, which tracks with a similar poll paid for by the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee in July.

If there’s any sort of blue wave in Texas, and if Joe Biden finds himself with coattails (the polling gurus at FiveThirtyEight currently give him roughly a one-in-three chance of winning here), then it’ll be because those new voters, who live exactly where Oliver needs them to be, were activated in the race. If she defeats Williams, the story of the 2020 election in Texas will be a story about the suburbs along I-35 completing the transition we began to see in 2018: from a GOP stronghold to a fully purple part of the state that can be contested by both parties.

Why It Probably Won’t

Even if there’s a dramatic realignment of the Texas suburbs and Oliver improves on her 2018 showing by a big margin, she still might lose by several points. She faces a heck of a gap for a challenger to make up against a well-funded incumbent in a presidential year, when incumbents who share a party with the president tend to do better than they do in midterms. Williams’s internal polling, which his campaign released in early September, draws a stark contrast with Oliver’s—it shows the Republican with a twelve-point advantage.

The Bottom Line

The Cook Political Report, which tracks congressional races, has this as “likely R,” a race that it doesn’t consider competitive at the moment but that has potential to end up that way. If Oliver wins, it means Democrats have probably picked up a lot of the seats they had targeted across the state. But a district that was drawn ten years ago to be one Republicans can win by 25 points is the kind where it’s a lot easier for a Democrat to claim a moral victory than an electoral one.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy