When Juneteenth became a federal holiday, a year and a half ago, and there were all those articles explaining its history, were you as surprised as I was to learn the symbolism behind our rituals? That the red food and drink served on that day represent the suffering of our ancestors and our fierce resistance? That the bursting lone star at the center of the Juneteenth flag, created just 25 years ago, stands for the holiday’s Texas origins as well as Black freedom reverberating through all fifty states? In the seventies my family and neighbors drank plenty of Big Red on Juneteenth, but it was pretty much the drink of choice for all summertime cookouts, reunions, and holidays. And I’d never heard of the Juneteenth flag, much less seen it fly, until our holiday went national.

My concern here isn’t that historians were making too much of things. Symbolism matters—it makes elusive connections tangible, which usually requires some artifice. When culinary scholars trace Texas-made Big Red to the red lemonade that was featured in early-twentieth-century Juneteenth celebrations—which itself was a version of the hibiscus and kola nut teas popular throughout the diaspora, from Jamaican sorrel to Senegalese bissap—I revel in the connection, like a child snatched at birth who is finally reunited with her family of origin.

But the focus on symbolism misses the point. What made Juneteenth meaningful to me, then and now, wasn’t the red fare or the new flag. It was that the holiday was ours, a holy day on which to savor each victory in the ongoing struggle for Black freedom. In his famous 1852 speech “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” Frederick Douglass skewered the irony of our enslaved ancestors being asked to celebrate the independence of a nation that denied them theirs. Similar hypocrisies abound around Juneteenth now. A new pamphlet from the 1836 Project advisory committee—a body formed by Governor Greg Abbott to push back against “revisionist” versions of Texas

history—includes Juneteenth “to reemphasize and make dang true that slavery was a bad thing and Texas participated,” member Donald Frazier said. That sentiment rings hollow, though, coming from a committee whose name honors a war fought in part to preserve slavery and whose pamphlet does not own up to that history.

Now that Juneteenth is a political pawn, not to mention a crass marketing tool (think of Walmart’s disastrous “Juneteenth ice cream”), those who have always found celebrating the holiday suspect—Why throw a parade to honor Black Texans being last to learn of slavery’s end?—may find it even more so. Gaining a national holiday that recognizes emancipation while the Supreme Court revisits voting rights, affirmative action, and due process decisions isn’t how freedom works. For those of us who cherish Juneteenth because our grandparents personally knew someone who rejoiced that day in 1865, the irony galls.

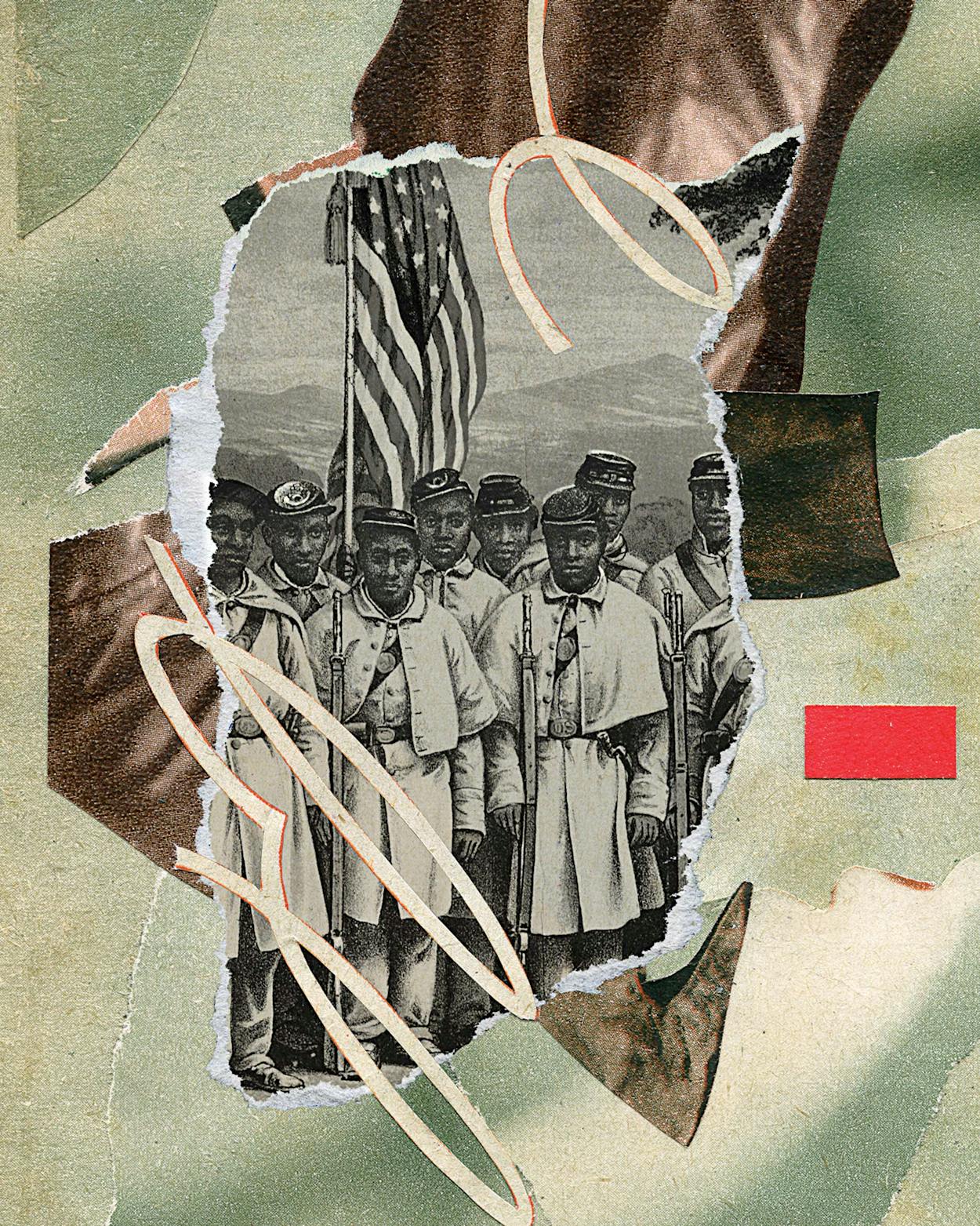

It takes walking the walk to make a symbol mean something. Opal Lee, the Fort Worth activist who, in 2016 at the age of 89, spent four months walking from her home to Washington, D.C., to bring Juneteenth to national attention, urges us to use the holiday to preserve our history. Few, for instance, know of the thousands of United States Colored Troops who joined

General Gordon Granger in liberating Black Texas on June 19, 1865. Or of the Emancipation Days that preceded Juneteenth, such as April 16, 1862, in D.C.; August 8, 1863, in Tennessee; and May 20, 1865, in Florida. The ritual of telling and retelling our Black freedom story reminds us that emancipation is a process, and ours is unfinished.

Had the nation’s Emancipation Day been January 1, 1863, the date the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, our celebrations today would coincide with those of Haiti, the first Black republic in the Americas, whose revolutionary spirit Douglass called Black Americans’ “bright example.” Our freedom came last in the U.S. because the Texans who supported slavery in 1836 were just as determined to do so three decades later. We must be equally resolute. Remembering Juneteenth, as our elders did and still do, will provide the “bright example” for the fight ahead.

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “On Juneteenth: Dear Fellow Black Texans.” Subscribe today.

Image credits: Black Soldiers: Bettmann/Getty

- More About:

- Politics & Policy