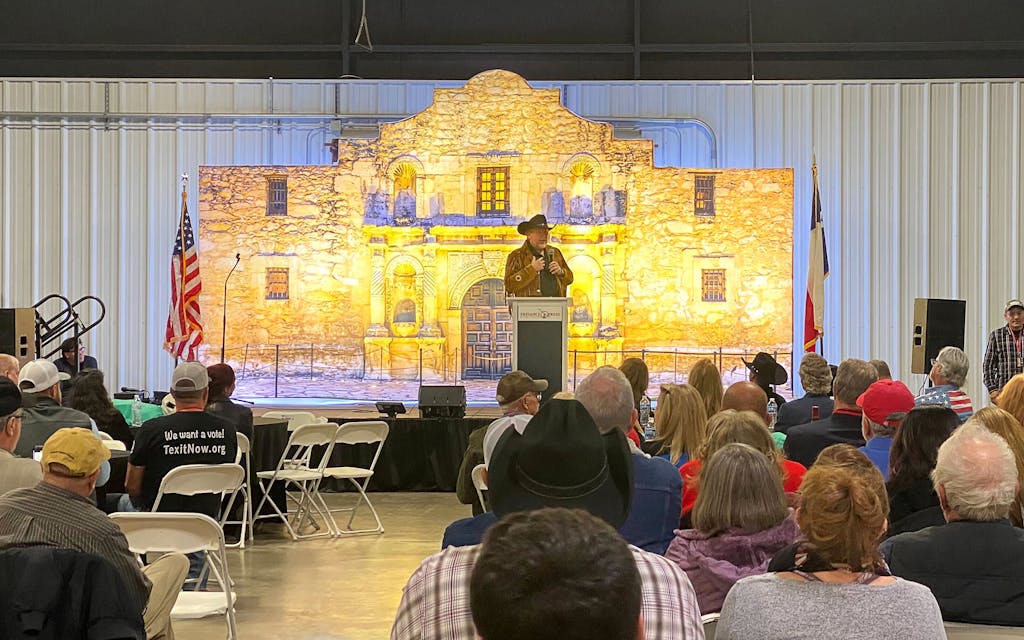

David Thomas Roberts took the stage brandishing a rifle and backdropped by a replica of the facade of the Alamo. Inside an exhibition room in the Montgomery County Fairgrounds recently used to host the local kennel club and a reptile show, he was leading the Rally Against Censorship an hour north of Houston. A crowd of a few hundred right-wingers listened intently, as he began his speech with a trigger warning. “I know there are children here, so I’m going to be careful, but I’m pissed off,” he said, before launching into an explanation of his anger.

The main outrage of Roberts, a prolific author and the founder of a right-wing press, concerned the media fracas surrounding his rally. In early January, Southern Star Brewing, a local taproom, had agreed to rent out its space to Defiance Press, which is based in Conroe. But then came a firestorm of criticism over the event’s headliner: Kyle Rittenhouse, the twenty-year-old who shot and killed two men and injured another at a Black Lives Matter protest in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in 2020 and was cleared of murder charges in a high-profile court case the following year. The brewery backed out in mid-January, saying it was “apolitical . . . but we feel that this event doesn’t reflect our own values.” (A spokesperson for the venue could not be reached, but its CEO told the Texas Tribune that he was not initially made aware that Rittenhouse would be a headliner; Roberts contends this was made clear to the venue from the get-go.) Roberts told his audience that Montgomery County Judge Mark Keough “weathered a storm” to make the exposition grounds available for the rally; the judge’s chief of staff said he had nothing to do with the rebooking.

Roberts presented himself to his crowd as a sort of Jane Goodall, reporting back to the audience about the ways of latte-drinking media elites, whom he had worked alongside when getting a novel published in the 2010s. “When you were walking into a publishing conference, it was like walking into a Star Wars bar, with those creatures,” he told the crowd. “My God, I couldn’t tell a man from a woman at those events.” Frustrated by difficulties getting publishers to accept and promote right-wing content, he said, he founded Defiance Press in 2011 to create a space for conservative and libertarian voices. Today, the company has published more than one hundred books—ranging from children’s offerings, such as one about a feline who wears horns to run in a race meant for antelopes (Looks Like a Cheetah to Me), to soberly titled political fiction (Fraud President), to Project Veritas–style nonfiction exposés of social media companies (Impact), to Robert’s own business-advice musings, offered under the moniker of “Renegade Capitalist.”

As a publisher, Roberts well knows the value of controversy. When it comes to his house’s books, “there’s no such thing as bad publicity,” he told the crowd. The cancellation of his event about opposing censorship only fired him up, he said, and proved the need for the gathering.

But if the initial cancellation spoke to the necessity of the event, so too, in a way, did holding the rally prove it an indulgence. Defiance had found a venue to host the event, in Roberts’s telling, with the help of government officials, and, once it began, speakers commanded the attention of hundreds of locals—far more than could have fit into Southern Star—who were spending their Thursday evening nodding along to discussion of the tyranny of the state.

Roberts understands free speech isn’t exclusively a concern of conservatives, and that he isn’t guaranteed an audience by natural rights. A day after the event, Roberts told me that, historically, the left has been censored more than the right, citing the McCarthy hearings of the 1950s and the treatment of anti-Vietnam protesters in the sixties and seventies. He also made clear that there was no free-speech issue with the event cancellation—he’s a small-business owner and doesn’t like regulations on whom businesses can serve—and that any publisher has a right to turn down his book proposals, just as he turns down manuscripts about LGBTQ issues or left-wing politics.

But free-speech absolutism wasn’t really the focus of his event as much as the evangelizing of right-wing politics was. The rally was indistinguishable in tone from the handful of tea party and MAGA events I’ve attended across Montgomery County, the largest deep-red county in the state, over the last year. Speakers recycled observational humor that had gone stale in the Bush era: liberals were all skinny-jeans wearing, Starbucks-sipping prisses. When things got sleepy, there were familiar call-and-responses that reinvigorated the crowd like the playing of “Sweet Caroline” during a seventh-inning stretch: questions from speakers about who had gotten the jab, greeted by boos, followed by questions about who knew someone who’d died from the vaccine, followed by solemn sighs. Nearly every speaker had a tale of being banned, or their posts being removed, from a social media site, which they spoke of as a grievous affront worn like a badge of honor.

The audience, ostensibly brought together in defense of free speech, yelled about Black Lives Matter protesters and cheered the Proud Boys, some of whom were in attendance. Daniel Miller, the leader of the Texas secession movement, littered a well-delivered speech with all the focus-tested flourishes he’s been offering for a decade about why Texas should leave the Union. An employment-rights lawyer from Frisco, Paul M. Davis, a.k.a. “Fired Up Texas Lawyer”—who is at once challenging vaccine mandates, school board policies on open-comment periods, and the tech giant Meta—called Joe Biden a “demented, fascist pedophile.” He regaled the crowd with his origin story: his employer fired him and his fiancée walked out after a journalist from Salon identified him via an Instagram post outside the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. (Davis says he never entered the building.) Not since the queen’s last visit to the USA had a trip to D.C. cost so much, no doubt, but it was unclear how exactly Davis thought he was being censored by reporters reporting on his public activity.

The more-specific critiques of our censorious times—with which the event approached living up to its billing—concerned Big Tech. Davis talked about being kicked off TikTok, and said Instagram had shadow-banned him, hiding his posts from other users. Roberts told me Facebook had rejected Defiance’s ads for its political books without explanation, and that Amazon had effectively throttled sales on one book, written by Miller and making the case for Texit, by raising its sale price to more than $300 without being prompted to. While he acknowledged that there should be some limits to what Facebook allows—it shouldn’t allow ads for a book teaching people how to be pedophiles, for example—he thought the social media giant should be regulated by the Federal Trade Commission as a “common carrier,” like telecom companies, which are considered so integral to the spread of information that they cannot deny service, as a small publishing house can.

The speakers’ critiques of Big Tech weren’t fringe—Supreme Court justice Clarence Thomas has made a similar argument—nor were they exclusively the province of the right. The role of social media companies as arbiters of acceptable political content deserves scrutiny, even if they are privately owned. But the people in the crowd didn’t seem particularly interested in a wonky discussion of the First Amendment. They had come to be energized by Kyle Rittenhouse, who, coincidentally, was a perfect poster child for both concerns about censorship and the way those concerns can quickly become obscured by cultural grievance.

Long before a jury exonerated Rittenhouse, he was exalted by many in the Texas right. On January 6, 2021, at a “Stop the Steal” rally in Austin, months before aerial FBI surveillance video crucial in clearing Rittenhouse was publicly released, a vehicle with a “We Are All Kyle Rittenhouse” banner made loops around the Capitol, eliciting rolling waves of cheers, as a parade float might. The crowd lovingly embraced the then-teenager known only for acts of violence against Black Lives Matter protesters.

I asked Roberts how he had decided that Rittenhouse, a cause célèbre on the right who has made innumerable media appearances, made sense as the featured interview of a rally on censorship. “Tell me somebody who’s had more cancellations on social media, more censorship,” Roberts dared me. In the run-up to his trial, Rittenhouse wasn’t able to fund-raise for court fees on GoFundMe. Facebook and Instagram removed his accounts and content praising or supporting him until he was acquitted, and, Rittenhouse believes, Twitter banned some of those who came to his defense. On top of that, Roberts had met “Kyle” before, and wanted to put a “human face” on a “good kid.”

Unsurprisingly, Rittenhouse was met with a standing ovation when he took the stage for his interview, but he seemed to slink back during the Q and A, keeping his answers brusque and holding the microphone so far from himself he needed to be interrupted to be told to project louder. Rittenhouse’s interviewer, Cassandra Spencer—a former Facebook employee who went to Project Veritas, a far-right group whose employees often go undercover to discredit liberal organizations, with evidence she believes proves anti-right bias at the company—tried to cajole him into discussing topics he wasn’t touching on, eventually relying on a sort of interrogational alchemy whereby she turned statements into questions by appending “Am I wrong?”

The interview began with a leading question. “Obviously, Kyle, censorship, both tech, media, and government, played a really big role in the lies that have been told about you,” Spencer said. “Explain how censorship has played a role.” Rittenhouse said his supporters had been banned from various social media platforms and, only when prompted by Spencer, noted what GoFundMe and Facebook had done before his trial. The crowd was mostly disengaged, until Spencer asked if Rittenhouse had ever worried that the reporting on his case would impact the trial and he replied, “A little bit, but I knew God was on my side.”

When given more-open-ended questions, Rittenhouse’s concerns veered far from censorship and toward its opposite: overexposure. The wide dissemination of his story had had an inconvenient consequence: it had shown him that many disliked him. He didn’t understand why “the entire left blows up” over his Twitter posts. Despite also blaming the media for silencing conservatives, he said he didn’t get why the press cared to cover him anymore. “I am twenty years old and I don’t know why the media is so focused on me,” he said, to an eruption of applause.

Indeed, despite the fact that this was a First Amendment rally, it was attacks on the press that seemed to gain the most purchase in the audience. When Rittenhouse called out the Washington Post and the Houston Chronicle and Spencer winkingly referred to them as “our friends” in the back of the room, nearly everyone in the audience swiveled around to send glares toward the media pool. Rittenhouse seemed especially concerned that many in the country thought he “had killed Black people,” a misunderstanding he blamed on the press and brought up repeatedly. (The two men Rittenhouse killed, as well as the man he shot and injured, were white.)

Spencer’s final question clarified Rittenhouse’s real criticism of the media: it wasn’t all favorable. She asked what advice he would give to someone who might be under media scrutiny—who is “the next Kyle Rittenhouse.” After some thought, he replied that everyone should support independent media and “other conservative media and platforms . . . that don’t have a bias,” the apparent contradiction lost on the crowd.

The event concluded with a bit of fan service. Event organizers opened up an online auction for a slot on a hog hunt at Roberts’s ranch, cigars included, with Rittenhouse. The proceeds, they explained, would go to a nonprofit Rittenhouse supports: K9s4COPs, which helps fund the purchase of drug-sniffing dogs for police departments. Some in the audience had already paid $500 for VIP passes that included private meetings with Rittenhouse before he spoke, but others pulled out their phones to put in bids. Cancellation had earned Rittenhouse such devotees.

Ten minutes away at Southern Star Brewing, the newest avatar of cancel culture for right-wing elected officials, patrons were speaking freely—about community gossip, reality TV, and, of course, the reality-television star who’d become president and, seven years later, still lends every sputtering conversation a useful crutch.

The bar’s patrons had gathered for a weekly trivia night—back on the calendar since the rally was off—and the rules of the game guaranteed that the brewery would be a safe space for unfiltered expression. The emcee opened proceedings with a “sensitivity disclaimer.” He would curse, and certain trivia topics might be “offensive to some.” The few parents who had brought their kids were warned to leave or otherwise deal with it and not write letters of complaint to their local representatives.

Surveying the room, it struck me just how odd it was that the venue had become a punching bag of the right. The walls were festooned with patriotic decorations, military paraphernalia, and pro-police flags. A corner of the bar featured a perennially unoccupied stool and a full, untouched glass of beer in tribute to Fallen Heroes. Many patrons said they were completely unaware of the controversy, and who could blame them: one consequence of the flattening of the free-speech debate to the concerns of fringe right-wingers on social media is that it’s hard to get someone who isn’t terminally online invested in the travails of an unknown Texan’s ban from TikTok.

One trivia player, a middle-aged man who had recently moved to a rural town in Montgomery County—a red pocket in a red pocket—told me he was glad that the rally had changed locations because trivia was “the one thing to do in town.” Besides, he wasn’t particularly concerned about censorship and had tired of all the politics talk. “What I love about living in Texas is I could have a raving-lunatic neighbor and never have to interact with them other than driving by their political signs,” he said. “That’s why I moved here.”

This story has been updated to include ways in which lawyer Paul Davis feels he’s been censored by big social-media companies.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Tea Party

- Conroe