The doorbell of Alex Triantaphyllis’s townhome in Houston’s Museum District began to ring repeatedly at 6:50 a.m. on March 11. So did his cellphone. When he opened his door he saw a Texas Ranger and two officials from the Harris County district attorney’s office standing at the locked gate, seeking entry. According to Triantaphyllis’s attorney, Marla Poirot, the Ranger’s vehicle was parked diagonally across his driveway, as if to prevent an escape, and its lights were flashing, drawing the attention of neighbors who emerged to see what the ruckus was about. Triantaphyllis, the chief of staff to Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo, spoke to the three officers at his gate.

As his wife and two daughters looked on, he examined a search warrant the officers had given him. Triantaphyllis retrieved and handed the officers a laptop computer and a smartphone; a separate team of investigators seized a second computer from his office in the county administration building downtown. Early that same morning, other teams from district attorney Kim Ogg’s office and the Rangers executed warrants seizing similar devices from the homes and offices of Aaron Dunn, a senior policy adviser to Hidalgo who transferred to another county department a few days after the raid, and Wallis Nader, Hidalgo’s policy director.

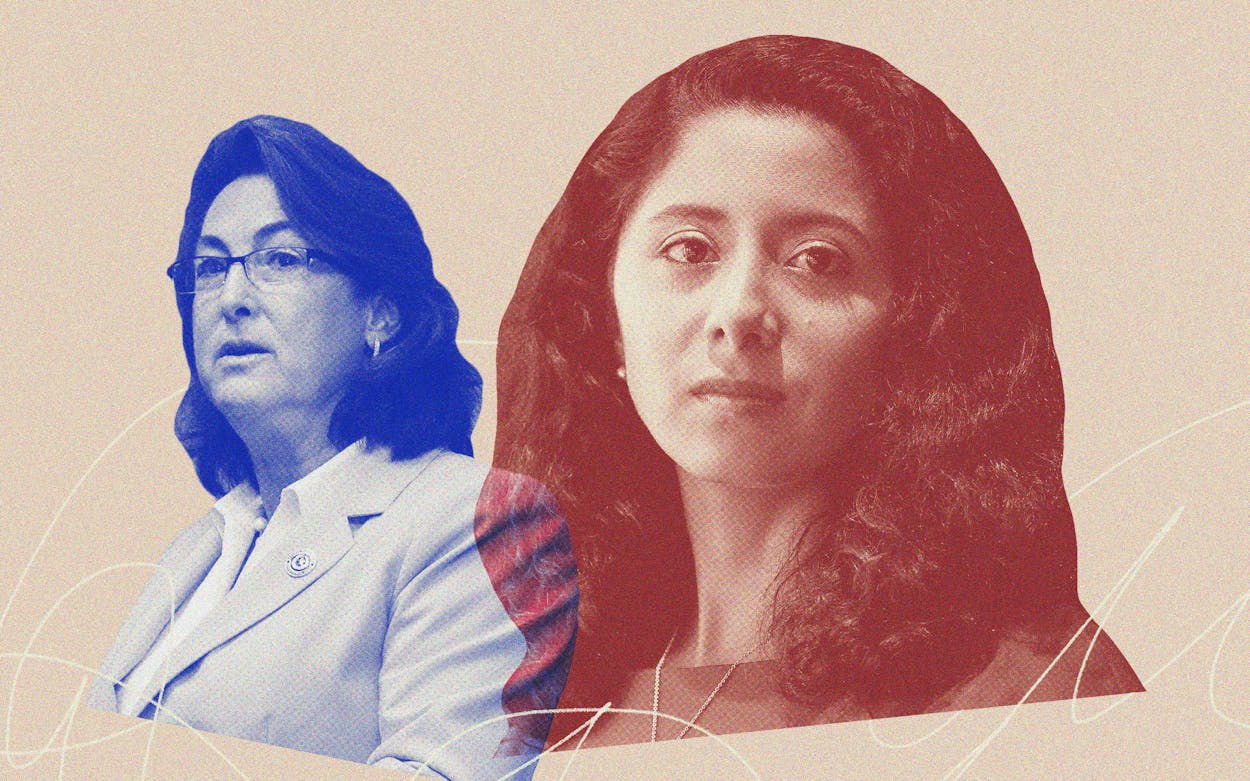

The raids were part of an intensifying criminal investigation into the county’s awarding of an $11 million vaccine outreach contract last June to Elevate Strategies, a firm led by Democratic consultant Felicity Pereyra, despite another bidder having rated higher in an initial assessment by a review committee. The contract was canceled in September after Republican county commissioners alleged that Hidalgo’s team had steered it to Elevate in a bid to nurture likely Democratic voters. The investigation threatens some of Hidalgo’s senior aides, and conceivably the county judge herself, a rising Democratic star who faces reelection in November, though she has said publicly that she was not personally involved in the selection process.

The search warrant for all three aides and lengthy affidavit supporting it, prepared by Texas Ranger Daron Parker, states that Parker believes information in the seized devices will show that Dunn, Nader, and Triantaphyllis committed misuse of official information, a third-degree felony, by “providing an advantage to a competitor” in a bidding process. It also says Parker believes they presented false statements on a governmental record—which can be either a felony or misdemeanor—by signing documents last year stating that they had complied with county ethics policies in awarding the contract. The affidavit shows that weeks before the public bidding process for the contract began, Hidalgo’s aides were communicating about COVID-related work with Elevate, and that Pereyra had access to details of the services the county wanted from the vaccine outreach vendor weeks before competing bidders saw advertised requests for proposals.

The excerpts of communications included in the search warrant affidavit create a narrative suggesting that, in effect, the fix was in. A review of the full text of dozens of documents—emails, memorandums, text messages, and WhatsApp conversations—provided to the investigators, and recently made available to Texas Monthly, reveals a more nuanced picture. The documents show that many—but not all—of the communications referenced in the affidavit concerned earlier plans for a separate project to analyze and distill COVID data and provide concise, regular reports to Hidalgo, a noted policy wonk who serves as the county’s emergency management leader as well as its chief executive. The distinction between the data project and the much larger vaccine outreach campaign is never acknowledged in the affidavit.

The documents also indicate that, at the time they were communicating with Pereyra before the bidding period for the contract was opened, county officials did not expect her to be a bidder because she said she was too busy to devote sufficient time to the smaller data analysis project. “I don’t think I’ll be able to help distill Covid insights to JLH (Hidalgo) in the near term given that my availability has changed since we started the conversation,” Pereyra wrote in a February 24 email to Triantaphyllis. It’s unclear how Pereyra, who has not responded to requests for an interview, found time to bid on, win, and begin work on the larger outreach project. (Before the contract was canceled, her firm was paid $1.2 million; county officials say they have recovered about $200,000 and are in the process of recovering most of the remainder.)

“When read in context, rather than the cherry-picked excerpts in the affidavit, the documents show a starkly different picture than what’s been painted in the press,” said Eric Gerard, one of Hidalgo’s attorneys. “They show folks at the county judge’s office working around the clock to protect people in the middle of a public health emergency. They show there were two different COVID-related projects under discussion at the same time, which the investigators appear to have confused.”

Dunn’s attorney, Dane Ball, did not return a call seeking an interview. David Adler, Nader’s attorney, called the allegations against his client meritless, while Poirot, Triantaphyllis’s attorney, said, “The accusations against my client are unsupported by a full and objective review of the facts.”

The criminal investigation focuses on communications in the first few weeks of 2021, a time when the coronavirus pandemic dominated the daily lives of Hidalgo and her senior staff. Case levels and hospitalizations were creeping upward, and the county’s threat level was at the highest category: severe, meaning the county government advised residents to “stay home” and “work safe.” Hidalgo and her top aides fired off emails and text messages at all hours of the day and night as they struggled to find strategies to push infection numbers down and to promote the use of newly available vaccines that promised to save thousands of local lives.

In text messages sent on January 5 that display some impatience, Hidalgo pressed her staff to move forward on the data initiative, saying she needed “consistent updates” on COVID. She wrote: “Please be sure I get specifics today on what is being done. We really need to turn the page on this.” It would be a relatively small project, Hidalgo and her aides decided, with no need for a competitive bidding process.

Discussions about potential vendors soon turned to Pereyra, whose work on a 2020 campaign to increase census response rates had impressed Hidalgo. During a January 7 conference call with staffers, documents show, Hidalgo first raised the idea of a separate, larger vaccine outreach project, focusing on underserved neighborhoods, that would include door-knocking and media campaigns.

Hidalgo’s team says that communication with Pereyra, at that time, was intended to be only about the smaller COVID data project. But shortly after midnight on January 13, 2021, Hidalgo’s staff contacted Pereyra with plans that included a vaccine outreach component. On January 15, Triantaphyllis sent Pereyra a second email clarifying that the scope of proposed work for her firm was limited to data collection and analysis, and a few days later told a colleague that the January 13 document was sent “incorrectly.” Nonetheless, five minutes after sending the email on January 15, he sent a third email to Pereyra outlining an initial strategy for the outreach project. Gerard, Hidalgo’s attorney, said Pereyra was sent this based only on the idea that Elevate’s data analysis work might include monitoring and reporting on the progress of the separate outreach effort. Two other January communications from Triantaphyllis made it clear that the scope of the data project would not include vaccine outreach.

The documents shared with Texas Monthly paint a picture of why, once the county opened the bidding process for the outreach contract, Hidalgo’s team might have not awarded the contract to the University of Texas Health Science Center, which scored higher on an initial assessment. Hidalgo’s camp appeared displeased at UT’s work on another COVID research project, Harris Saves, which was intended to more accurately measure countywide prevalence of the virus but which failed, according to county officials, because not enough participants were recruited. In conversations, aides disparaged UT. “This data outreach thing is getting ridiculous,” Triantaphyllis wrote in a WhatsApp conversation with Nader on April 20. “We need to slam the door shut on UT and move on.” A spokeswoman for UT Health Science Center, Jeannette Sanchez, declined a request for an interview.

Beyond its potential legal consequences, the contract investigation reflects long-standing tensions between Hidalgo and Ogg, the Democratic district attorney who has found an alliance with the two Republicans on the five-member commissioners’ court, chaired by the county judge. In recent months, the Republicans, Jack Cagle and Tom Ramsey, have generally supported Ogg’s requests for funding beyond the annual increases her office has received, while the three Democrats—Hidalgo and Commissioners Adrian Garcia and Rodney Ellis—have resisted her entreaties. Ogg also increasingly finds herself estranged from the progressive wing of her party, which has faulted her for not embracing reform of the cash bail system.

Attorneys for two of the three Hidalgo staffers named in the search warrant affidavit told Texas Monthly that, given these political tensions, they are suspicious of Ogg’s motives in the criminal inquiry. “The way this investigation has been conducted raises serious concerns that it is part of an agenda designed to attack committed public servants for political gain,” Poirot, Triantaphyllis’s attorney, wrote in an email. Adler, Nader’s attorney, agreed in a phone interview: “It seems to me to be much more than a coincidence that the DA has chosen to investigate the county judge when the county judge has rejected money for more prosecutors.”

Ogg declined an interview for this story, but shared a statement from her spokesman, Dane Schiller, declaring that “Since the State of Texas disbanded the Public Integrity Unit, which was housed at the Travis County District Attorney’s Office, the responsibility for such work has landed on district attorneys across the state; our prosecutors follow the evidence wherever it leads and apply the law equally to all.”

Keir Murray, a Houston-based Democratic consultant who is not affiliated with Ogg or Hidalgo, suggested that tension between the two officials might in part reflect “growing pains” on the part of a newly empowered Democratic majority on the commissioners’ court. “Democrats have gained total control over county government,” making the two Republican commissioners largely irrelevant, Murray said. “Without that normal adversarial aspect, the dynamic becomes one person or faction in one party versus another.”

Eleven days after the investigators seized the devices, Ogg appeared before the commissioners’ court to make the latest in a series of unsuccessful pleas for more funding for her office, accusing county officials of “defunding” law enforcement while crime rates rise. Her request for $6.17 million for hiring and raises was tabled, however, on a 3–2 vote, with Hidalgo, Garcia, and Ellis on the prevailing side. At a news conference during a break in the court session, questions focused less on the meeting than on the criminal investigation, with journalists shouting over one another in a scene reminiscent of a presidential press gaggle. Ted Oberg of KTRK-TV, Houston’s ABC affiliate, told Hidalgo that Ogg had “suggested” that reporters ask the county judge whether she had received a letter indicating she was a target of the investigation. Hidalgo deferred the question to her attorneys.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Lina Hidalgo

- Houston