In December 1969, a young Dallas attorney typed a letter to a fellow lawyer and former law school classmate in Austin, catalyzing a journey that would alter the landscape of abortion rights for the next five decades.

“I am very enthusiastic about the possibility of your organization in Austin . . . bringing an action to challenge the Texas Abortion Statute,” wrote Linda Coffee, 26, to Sarah Weddington, 24, who was working with a women’s rights group that was researching ways to challenge the state’s abortion law. “Would you consider being co-counsel in the event that a suit is actually filed. I have always found that it is a great deal more fun to work with someone on a law suit of this nature.”

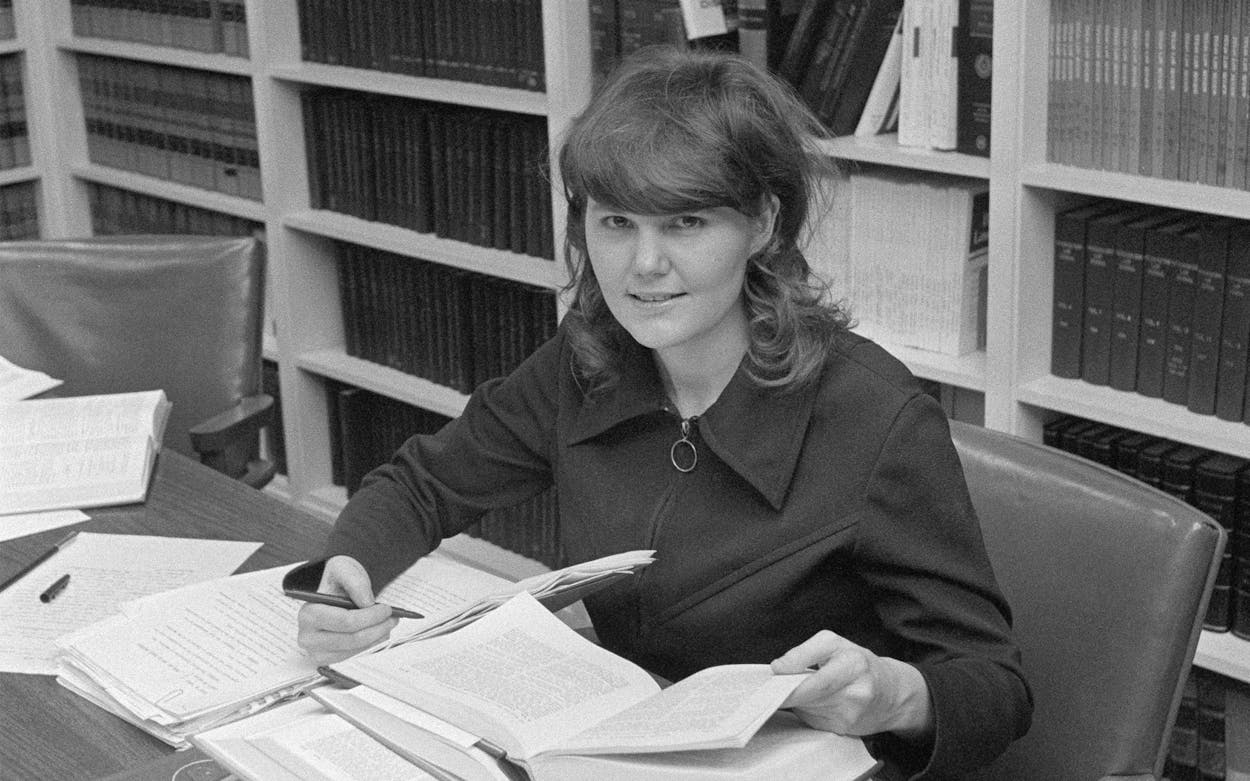

While Weddington ultimately argued Roe v. Wade before the U.S. Supreme Court, it was Coffee who filed the suit in Dallas against District Attorney Henry Wade, found the plaintiff, presented half the oral argument in the Northern District of Texas U.S. District Court, appealed the ruling to SCOTUS, and invited Weddington to join the case. Coffee, using precedent from the 1965 Griswold v. Connecticut ruling that upheld the right to privacy when it came to contraception, challenged Texas’s law that criminally barred abortion care except when needed to save the life of the patient. While a three-judge district court panel in Texas found the law to be unconstitutional, it also failed to grant an injunction to prevent enforcing it, allowing for an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

While her cocounsel—who later became a state lawmaker and a popular activist—felt comfortable in the public eye for many years after the ruling, Coffee—a self-described introvert—chose to remain reclusive, giving few media interviews over the following decades.

At age eighty, Coffee has decided to auction her entire Roe v. Wade archive, nearly 150 documents and letters—including her law license, the original affidavit signed by Norma McCorvey (“Jane Roe”), and her letter to Weddington—on the fifty-third anniversary of when she filed suit in Texas, March 3, 1970.

Born in 1942 and raised in a Southern Baptist family in Dallas, Coffee excelled in school, eventually graduating from Rice University and then the University of Texas School of Law in 1968. Coffee had high bar exam grades, but it was rare for women to find jobs at male-dominated law firms in the late sixties. Coffee ended up working at the Texas Legislative Council, helping state lawmakers draft bills. When her mother heard of an open clerkship position with Sarah T. Hughes, the first woman appointed as federal judge in Texas, Coffee eagerly applied. Coffee’s time assisting Hughes in civil cases and watching her mentor work on gender-discrimination suits was instrumental in shaping her passion for justice and equality. Following the Roe v. Wade ruling, Coffee transitioned into bankruptcy law and largely stayed out of the spotlight. Today, she lives with her partner, Rebecca Hartt, whom she met in 1983, in Mineola, a town east of Dallas.

Coffee stands as one of the last remaining figures who were part of the historic case. McCorvey died in 2017, Wade in 2001, and Weddington in 2021. As the only major player involved with Roe who has witnessed its demise, Coffee reflects on her career, the seminal abortion-rights ruling she helped secure, and the Supreme Court’s overturning of it some fifty years later.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Texas Monthly: When you graduated law school and started your career in the late sixties, it was a male-dominated world, and the legal field was no exception. What struggles did you face?

Linda Coffee: There were only about four or five other women at UT law school while I was there. One of my professors either didn’t like having women in his class or just didn’t want to accept it, so he would call me Mr. Coffee. After graduating, not many law firms were hiring women at the time, so it wasn’t easy to get a job. And I had tied for the second-highest score in the state on the bar exam, and it was still very difficult. I was appreciative that [U.S. judge] Sarah Hughes hired me as a clerk; she was really serious about civil rights and believed that women should have the same opportunities as men. She was respected; she was the first woman appointed as a federal judge in Texas. She swore in [Lyndon B. Johnson] on Air Force One after Kennedy was assassinated—the first woman to give the oath of office to a president.

And one memory that will always stick with me when we talk about how male-dominated things were back then is when we were at the Supreme Court, they didn’t even have a restroom for women on the main floor, so we would have to climb down three flights of very long stairs in our high heels to find one. I hope they have changed that by now . . . [laughs]

TM: What motivated you to challenge the Texas abortion law and file Roe v. Wade in 1970?

LC: I had worked on gender-discrimination cases and was part of the women’s movement in Dallas. I would attend meetings with the [Women’s Alliance] at the First Unitarian Universalist church, who were interested in abortion rights, so it was something that was on my mind. On Saturdays I would visit the SMU [Southern Methodist University] law library, and when I was there one day in 1969, I came across a California state Supreme Court ruling from just a few days ago, People v. Belous. It found the state’s abortion ban unconstitutional [on the grounds that it violated the due process clause and the right to privacy]. It really opened the door for me to start thinking about what could be done in Texas. I thought, “The same arguments here could be made against the Texas abortion law.”

TM: You were the one to secure Norma McCorvey, a.k.a. Jane Roe, as a plaintiff. How did you find her?

LC: My good friend, Henry McCluskey, who I had known since high school, was an adoption attorney. I had helped him work [behind the scenes] on a case challenging the Texas laws against sodomy, which included the constitutional issue of privacy. He was a gay man and out; I am a gay woman but was not public about it yet, so I didn’t put my name on the briefs. Working on that case helped me challenge the Texas abortion law. If privacy can be extended to sexual activity, it could also extend to terminating a pregnancy.

When I needed a plaintiff, he told me he had a client who was pregnant and wanted an abortion, but of course, it was illegal in Texas. [McCorvey] agreed to be a plaintiff in the case. However, she was not able to get an abortion before the ruling’s impact and ended up giving birth to a daughter, who she placed for adoption.

TM: How do you feel about McCorvey’s later evolution into an anti-abortion activist?

LC: I would hear her speaking against abortion, and I remember once seeing her getting baptized in a swimming pool—I didn’t care for all that too much. But when she was on her deathbed later, she said she was actually pro-choice and that she was being paid by the anti-abortion people and that she had needed the money. The whole thing made me sad. I’ve been contacted many times over the years but never wanted to be an opportunist. We filed the lawsuit not for money or fame, but based on principle.

TM: What was your reaction when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last year in its Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling?

LC: When the opinion was leaked by Politico [in May 2022], I was completely shocked and disappointed. I was amazed to see them declare that there was never a constitutional right to abortion. I still don’t understand who leaked the opinion; I suspect it was a law clerk of one of the conservative justices.

And when the official ruling came down, I was still very disappointed, just not as surprised. I thought maybe they would just ban abortion after fifteen weeks, but it’s clear they don’t want women to have control over their bodies; they want to force people to stay pregnant. I also can’t understand how it could have happened this fast—it wasn’t that long ago that the Supreme Court favored at least some kind of abortion rights. It seems to be more about politics than the rules of precedent. To see it all come full circle in this way is very depressing.

TM: Even before Roe fell, Texans were living under Senate Bill 8, a near-total abortion ban, because the U.S Supreme Court allowed it to take effect in September 2021. Rather than having the state enforce penalties, it allows for private enforcement, meaning any person can sue an offending abortion provider. What do you think of that law?

LC: I think it’s horrible. It encourages citizens to police and monitor Texans, to invade the privacy of others. It reminds me of something from a George Orwell novel.

TM: Why did you decide to place your historic Roe v. Wade archive items up for auction? Are there documents in particular that mean the most to you?

LC: I’m eighty now, and I just want to make sure my collection is around for people long after I am gone. I think my letter to Sarah [Weddington] means a lot because that was the start of our journey, and she immediately agreed to help me with the case. I also have the receipt from the fifteen-dollar fee to file the lawsuit in Texas—now everyone files on the computer, but I did it in person back then. And the quill pens given to us by the Supreme Court when we argued the case—that was special.

Of course, all these memories are bittersweet now.

TM: There is a deep sense of despair when it comes to reproductive rights in the U.S. right now—especially here in Texas. Is there a message you want to send to people who are feeling defeated?

LC: It’s going to take much more than what I did all those years ago. But I really have faith in this new generation to get choice back. I know there is a lot of dismay right now, but we must regroup and not be intimidated to keep fighting. It may take a long time, but I know things will get better.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy

- Abortion

- Mineola

- Dallas