Welcome to our primary live blog. Our plan is to update every fifteen minutes or so before polls close, and then even more regularly once we have results. We encourage you to occasionally refresh your browser so you can see the most recent update.

Catch up on the latest

- Greg Abbott has won the GOP nomination for governor and will avoid a runoff. He will face Beto O’Rourke in November.

- Ken Paxton will face George P. Bush in a May runoff for the GOP nomination for attorney general.

- In South Texas, AOC-backed Jessica Cisneros and nine-term congressman Henry Cuellar are heading to a runoff in the Twenty-eighth Congressional District.

- Van Taylor, who was narrowly forced into a runoff by Keith Self in his North Texas U.S. House district last night, admitted to an affair and withdrew from the campaign Wednesday afternoon.

- Greg Casar, a democratic socialist, has won his primary in an Austin-to–San Antonio U.S. House district, where he’s all but certain to prevail in November.

- Sid Miller defeated James White in the Republican race for agriculture commissioner.

- Why is voter turnout so low?

The Van Taylor Affair

Forrest Wilder, 6:15 p.m.

Van Taylor’s Republican opponents thought he would be defeated over disloyalty to Trump. Instead, he was defeated over disloyalty to his wife. In what has to be one of the weirdest, most abrupt ends to a political career, Taylor, a congressman who represents North Texas’s Collin County, admitted today to an affair with a woman known in British tabloids as the “ISIS bride” and announced that he would not campaign for reelection.

Yesterday, Taylor seemed poised to avoid a runoff, staying above 50 percent for much of the night against his four Republican opponents as the early votes were counted. But as Election Day votes came in, he dipped just below the critical 50 percent threshold by hundreds of votes, thrusting him into a runoff with the second place finisher, former Collin County Judge Keith Self. Now Taylor has effectively conceded his office to Self, who’s likely to win in November and who must be stunned to find that texts about “slow rim jobs” have handed him a job he expected to win by hammering Taylor over his votes to certify the election and appoint a commission to investigate the January 6 mob.

The salacious story broke, as many right-wing sex scandals do these days, on far-right media. National File published the first piece on Sunday, two days before primary day, with the headline “EXCLUSIVE: Van Taylor Accused of Extramarital Affair With ISIS Bride, Abuse of Power, ‘Rim Job’ Text.” The woman, Tonia Joya, told the site that she had had a nine-months-long affair with Taylor from October 2020 to June 2021 after they connected over Joya’s work preventing violent extremism. The subject of a profile in Texas Monthly in 2017, Joya gained public notice in the previous decade because of her marriage to John Georgelas, a Texan man from Plano who became the top American ISIS leader in Syria. Eventually, Joya grew disenchanted with her husband’s extremism and the travails of living in a war zone and fled Syria. Her strange and harrowing journey brought her to Texas and into the less exciting world of Congressman Van Taylor.

According to the Dallas Morning News, it was Taylor’s reelection billboards that prompted Joya to come forward. She connected with Suzanne Harp, the third-place finisher in the race, last week to talk about the affair. “All I wanted was for Suzanne Harp to just say, ‘Hey, I know your little scandal with Tania Joya. Would you like to resign before we embarrass you?’ But it didn’t happen like that,” Joya told the Dallas Morning News. But Harp had other plans. She dispatched someone to record Joya’s story. National File then published its “EXCLUSIVE” along with audio of the 30-minute interview (Joya: “my story is about my love affair with Van Taylor”) along with salacious texts purportedly from Taylor to Joya. Then, on Monday, Breitbart published another piece purporting to show that Taylor had made a $5,000 payment to Joya, which the publication described as “hush money.”

It’s impossible to know for sure, but given the Election Day fall-off in support for Taylor surely at least some voters had “ISIS bride” and “slow rim job” and “hush money” on their minds when they went in the voting booth. If the scandal had broken a day later, perhaps Taylor would have avoided a runoff and instead of apologizing and resigning, he would merely be apologizing. But that’s all a counterfactual. The bitter reality is that one of the few Texas Republicans to stand up to Trump and acknowledge that Joe Biden won the 2020 election has now been undone by his infidelities. Donald Trump, no stranger to extramarital affairs, must be having a chuckle somewhere.

Conservative Black Democrat Harold Dutton Is Still in Jeopardy

Ben Rowen, 5:32 p.m.

Harold Dutton, a Black Democrat with a conservative bent, has represented a slice of Houston in the Texas House since 1985, and for most of the 2000s never even garnered primary challenges. But in 2020, a challenger in a three-way primary forced Dutton into a runoff, which he won. In the 2021 Lege session, he was put in charge of the Public Education Committee by Speaker Dade Phelan. The session proved testy for Dutton: after a pet bill of his calling for a state takeover of certain Houston public schools was killed on a technicality by a fellow Democrat, he seemed to retaliate, reviving a bill targeting trans student athletes. “The bill that was killed last night affected far more children than this bill ever will,” Dutton said, defending his actions when he drew progressives’ ire.

This year, Dutton drew a spirited opponent in his primary: Candis Houston, the president of the Aldine American Federation of Teachers, who had the backing of the statewide branch of that organization and the AFL-CIO, as well as the progressive PAC Annie’s List. The House Democratic Campaign Committee backed Dutton. Houston has distinguished herself from the incumbent primarily by framing herself as a staunch defender of public education, but has also criticized anti-trans legislation.

Harris County has been especially slow to count ballots this year, as we’ve noted, but as the race currently stands Dutton has a lead of only 120 votes. With no other opponents in the race, there won’t be a runoff and whoever wins will get the party’s nomination. This one is worth monitoring.

Jeff Younger, Prominent Anti-Trans Activist, Reaches a Runoff

Christopher Hooks, 5:21 p.m.

If you get your news from the “lamestream media,” you may not have heard of the Younger family, who have been headline news in conservative media for years. Now, one of the main characters in the saga has secured a spot in a runoff for a state House nomination—which means that the family may become better known over the next few years.

Jeff Younger and his wife, Anne Georgulas, are divorced, and at first, had shared custody of a child. Georgulas reports that, by age three, their child identified as a girl, growing out her hair and wearing dresses. Jeff alleges that Georgulas is forcing the child, now nine years old, to identify as female, and started a public campaign, becoming a crusader for “men’s rights” in the process. Last year, a court reviewed the evidence brought forward by both parties as to who was a more suitable parent and gave full custody to Georgulas.

This year, extending his fight, Jeff launched a campaign for Texas House District 63, in Flower Mound. Though Younger ran on a number of issues, there was a particular focus on stopping the “abuse” of trans kids. “I’ve spent over a million dollars trying to stop my ex-wife and the courts from chemically castrating my son,” relates his campaign website. “An economic crisis for any family. Texas can do better. PERIOD.” A jeremiad against teachers, psychologists, doctors, courts, and the Legislature for failing to pass bills ensuring kids can’t transition follows.

The treatment of transgender children, whose existence many Republicans deny, has become a big issue in the GOP primary, as reported on earlier in this blog. Last night, in a field of four, Younger narrowly placed second with 27.5 percent against leader Ben Bumgarner’s 29 percent, forcing a runoff. (Bumgarner is the co-owner of a gun manufacturing company called Evolve Weapons Systems.) This race is one to watch. If Younger makes it to the Legislature in this very GOP-friendly district, he’ll become a face of legislation about transgender children in coming sessions.

The Success of a Democrat-Turned-Republican

Christopher Hooks, 1:07 p.m.

Ryan Guillen lives! In November, state Representative Ryan Guillen switched parties from D to R, a major win for the GOP as it continued to emphasize its growth in South Texas and the Rio Grande Valley. Guillen was one of the most conservative Democrats in the House, but he generally had a reputation as an un-ideological and lobby-friendly fellow—his most notable legislative victory in recent years was a bill to greatly lower the sales tax on yachts, which was of limited use to the residents of his pretty poor district.

So it was an open question how Guillen would fare in today’s Republican Party, which demands a pretty high level of ideological fealty—even as Greg Abbott and Speaker of the Texas House Dade Phelan rushed to endorse him. Party switchers in South Texas have a mixed record. State Rep. J.M. Lozano switched to the Republican party in 2012 and is still there today—but State Rep. Aaron Pena defected to the GOP in 2010 and was pushed into retirement soon after. Guillen had two primary challengers, who set about making the case that he was not a real Republican—while elected Republicans set out to defend Guillen, thinking him a more valuable prize.

They succeeded. Guillen won 58 percent of the vote last night, with second-place finisher Mike Monreal scoring 36 percent. Guillen is likely to win re-election in November—he defected primarily because his district had been made more Republican. Perhaps in time, he’ll abolish the yacht sales tax altogether.

A Note on Democratic Turnout in South Texas

Jack Herrera, 12:24 p.m.

As the sun rose across South Texas, from Laredo all the way down the Rio Grande to Brownsville, the final counts in the March 1 primary made one thing clear: Democrats had shown up in much, much higher numbers than Republicans.

In the Fifteenth Congressional District, anchored in McAllen and where Republicans have their best shot at flipping a soon-to-be vacant seat, Democratic primary voters outnumbered Republicans by about 20,000 to 16,000. The daylight between the Dems and the GOP was even greater in the Thirty-fourth, anchored in Brownsville, at 29,000 to 10,000, and the Twenty-eighth, anchored in Laredo, at 24,000 to 13,000. But turnout in primaries often does not predict the results of the general election. And in South Texas there’s another confounding factor: many Republicans vote in the Democratic primaries.

Because city and county offices in Laredo have long been dominated by Democrats, there are often no Republicans running in certain races (though some Republican super PACs are trying to change that). That means that many Republicans who want to vote on local political issues in the primaries have resorted to casting ballots in Democratic races. “It’s not fair, but that’s the way the system is,” said Juan Ramirez, a Laredo business owner who cast his vote yesterday in the Democratic primary.

Yesterday, outside the Guerra Centre, a polling place in central Laredo, Ramirez told me he’s supported Republicans every year since JFK’s assassination. However, that didn’t stop him from voting enthusiastically for a Democratic congressman in the primary. Though Ramirez lambasted the Biden administration and the policies of national Democrats, he said he’s a longtime strong supporter of Henry Cuellar.

“He’s one of the few Democrats who [extends his] hand to the Republicans sometimes,” Ramirez said, explaining that he admires that Cuellar is willing to break with party leadership and vote with the GOP on certain key issues, such as increased oil drilling, aggressive border enforcement, and anti-abortion policies. He also admires the funding Cuellar has managed to bring to Laredo, in part through the congressman’s position on the powerful House Appropriations Committee.

“All the years he’s been in office, he knows how to get the money for the city, he knows how to do things, and he does them,” Ramirez said. “With the infrastructure, with the airport—sometimes we have problems with water and sewer, and he gets involved.” (Over the last week, much of Laredo went without running water, and many houses are still under a “boil water” notice now that service has been restored. Cuellar has frequently posted updates on social media and has said his team is distributing bottled water to residents.)

Cuellar has long courted votes from right-wing voters. A self-proclaimed Blue Dog and one of the most conservative in his caucus in the House, Cuellar represents an increasingly rare breed of Democrat. His unique stances speak to the complexities of politics in South Texas. He has built his reputation—and staked his political future—on the bet that South Texans want a centrist, conservative Democrat representing them in Congress. “Some of my Hispanic colleagues have told me, ‘You’ve got to be careful about the way you vote,’ ” Cuellar told me in 2021, explaining how he’s taken flak for his conservative stances. “I tell them, ‘I think I know my district, and I think I know it better [than you do] … I’m doing what I think is right, listening to my folks.’ ”

Jessica Cisneros, an AOC-aligned immigration lawyer, is trying to prove Cuellar wrong. Last night, she and Cuellar both succeeded in making the runoff election for the next primary vote on May 25. Cisneros is running an unapologetically left-wing campaign, supporting Medicare for all and the Green New Deal, as well as more humane border and immigration policies.

The Other Big Democratic Runoff in South Texas

Ben Rowen, 11:41 a.m.

One Texas Senate race I highlighted yesterday merits a follow-up—the Democratic primary to replace retiring Democrat Eddie Lucio Jr. in a South Texas seat anchored around McAllen. With redistricting and the rightward shift that happened in the Rio Grande Valley in 2020, Senate District Twenty-seven figures to be more competitive than it’s been in a long time. A wide spectrum of Democrats entered the race, which will be heading to a runoff. “Different Democrat” Morgan LaMantia, an attorney and Democratic donor who earned the endorsement of Lucio—who was the most conservative Democrat in the Senate last session—will face off against attorney Sara Stapleton-Barrera, a progressive who forced Lucio into a runoff in 2020 before falling short. This year the race, like the U.S. House runoff in Congressional District Twenty-eight between Henry Cuellar and Jessica Cisneros, will test whether Blue Dog-style Democrats, who’ve long dominated South Texas politics, are losing ground to progressive Democrats.

Cuellar and Cisneros Advance to Runoff

Jack Herrera, 9:54 a.m.

As the clocks ticked past 2 a.m., the Associated Press called the Democratic primary for the congressional seat in District 28: It was going to a runoff on May 24. Incumbent Congressman Henry Cuellar and Jessica Cisneros will face a rematch in May, after both failed to pass the 50 percent threshold to win outright. After trailing in the count most of Tuesday night, Cuellar had taken a slim lead with nearly all the votes tallied. This morning, with 95 percent of the vote counted, Cuellar led Cisneros 48.5 to 46.8.

About three hours before the vote was called, Cisneros spoke to her family and supporters at a jubilant watch party in northeast Laredo. “It’s not looking like we’ll have results tonight,” she said, as a projector flashed up a live vote count that showed her holding a slim lead. Unable to read her victory speech, Cisneros talked about how the closeness of the race was its own sort of victory. When Cisneros, an immigration attorney, announced her first run against Cuellar back in 2019, the high-ranking House Democrat seemed invulnerable. Then serving his eighth term and backed by a powerful network of businesspeople and local officials in South Texas, Cuellar was sometimes called “The King of Laredo”—a moniker that wasn’t always a compliment. Aided by Justice Democrats, the left-wing PAC that recruited Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez during her upset primary win in New York, Cisneros almost took Cuellar down: He spent $2 million to beat her by just under 4 percentage points.

Two years later, Cisneros said, the even tighter race was just more proof that her progressive vision—including universal health care, massive investment in green jobs, and welcoming immigration reform—is working in South Texas. “We are showing that our dreams can compete, neck and neck,” she said. “We’re going to prove that we, as a people, are more powerful than any kind of money that they put their faith in.”

The primary was marked by drama—and not just the usual campaign fireworks. In late January, FBI agents raided Cuellar’s Laredo home and campaign office. The FBI later said the raid was part of a wide-ranging FBI probe into a group of US businessmen and the government of Azerbaijan. Though Cuellar has not been indicted—and says the investigation will clear him off any suspicion—the raid likely hurt him on Tuesday.

A third candidate in the race, Tannya Benavides, also ran to Cuellar’s left. Benavides finished with just less than five percent of the vote.

That’s All for Tonight, Folks

Ben Rowen, 12:56 a.m.

Twelve hours in, we’re going to call it a night here. Thanks for following along.

The headline results of the night are Greg Abbott’s outright win in the GOP gubernatorial primary, Ken Paxton and George P. Bush qualifying for a runoff for the GOP nomination for AG, and democratic socialist Greg Casar’s win in a U.S. House primary in a deep blue district that all but assures he’ll be the representative next year.

Be sure to check back in the morning for updated results on two races: the Democratic primary in the Twenty-eighth Congressional District, anchored in Laredo, where incumbent Henry Cuellar and Jessica Cisneros appear to be headed to a runoff, and the Democratic primary for attorney general, where former ACLU lawyer Rochelle Garza will face a runoff opponent—though it’s not yet clear whom.

Closing Thoughts

Christopher Hooks, 12:46 a.m.

God makes all primary seasons in his image, but he likes some of them more than others. Some are packed to the brim with lunacy and derangement, or set in motion ideological shifts that change the state for good. Others kinda sputter. This one sputtered.

The Republicans who run state government have each been there for two terms, enough to get dinged up. But Greg Abbott won renomination with 70 percent of the vote over some very loud challengers, and a guy named Rick Perry (not that Rick Perry). Dan Patrick has his fair share of intraparty detractors, but he got no challenger worth mentioning. An attempt to unseat Sid Miller fizzled. Ken Paxton had three strong challengers and was forced into a runoff, but none of his opponents ran particularly strong either—with second place finisher George P. Bush running twenty points behind. In the House, Speaker Phelan helped defend his incumbents. In the Senate, Patrick helped elect new loyalists. This one’s pretty standard, as these things go.

Underneath Beto O’Rourke, the results for Democratic statewide races suggested that most Democratic voters are picking names at random for many offices when they step into the voting booth. This is also not new. There will be a few crackerjack runoffs—particularly Paxton versus Bush, and Henry Cuellar versus Jessica Cisneros for the U.S. House in South Texas. Then we’ll go to the general election, where vanishingly few districts are competitive and the outcome of most races will seem preordained. It’s called Democracy, folks, and it’s a beautiful thing.

Morgan Luttrell Waits for Harris County

Michael Hardy, 12:40 A.m.

Shortly after midnight, retired Navy SEAL Morgan Luttrell took the microphone in the Houston suburb of Conroe to announce . . . that the crowd would have to wait a bit longer. Luttrell, who is running to represent U.S. House District 8, currently leads an eleven-person field with 53.1 percent of the vote and is aiming to stay above 50 percent to avoid a runoff. The deep red district runs from the Houston suburbs north to the Davy Crockett National Forest, near Lufkin. An estimated 90.6 percent of votes have been counted, but Harris County is filling its traditional role as an election laggard and has reported fewer than two hundred votes, almost evenly divided between Luttrell and his closest competitor, Christian Collins.

“I want to be able to tell you it’s done, but Harris County has not come through yet,” Luttrell told the crowd of a couple hundred supporters, many of whom have been waiting since 7 p.m. The crowd has thinned a bit, but plenty of people remain, eagerly anticipating a victory speech. Luttrell said he wanted to be absolutely sure he had avoided a runoff before making an announcement. “I never want to mislead you, so I’m not calling this thing yet,” he said. “It’s going to be a long night. But we’re doing great.”

Luttrell said he would stay at the election watch party until Harris County reported its votes, and invited the crowd to stay with him. Most of them appeared to take him up on the offer, settling in for a long wait.

Dan Patrick’s Candidate Appears Likely to Prevail in Amarillo

Ben Rowen, 12:34 A.m.

Earlier today I wrote about the Texas Senate race to replace Kel Seliger, a sometimes Dan Patrick–crossing Republican in the Trumpiest district in the state. In November, after Seliger refused to support a bill to require a full audit of the 2020 Texas election results, which Donald Trump had called for despite his win here, the former president endorsed Midland oilman Kevin Sparks. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick followed suit. Seliger announced his retirement.

The race to replace him hasn’t been called yet, but Sparks is above the 50 percent threshold needed to avoid a runoff, with 97 percent of the vote in. Should he hold on to that lead, he won’t face a Democrat in the general election, and Patrick will have the fully compliant GOP caucus in the Senate he has long been building.

Close, but No Cigars Were Lit at Jessica Cisneros’s Watch Party

Jack Herrera, 12:26 A.m.

The mood at Jessica Cisneros’s election night watch party in Laredo reached a level close to euphoria at just past 7 p.m. on Tuesday night, when the early results showed her leading incumbent Democratic congressman Henry Cuellar by as many as forty percentage points. By the time Cisneros herself took the stage four hours later, however, the most likely result looked to be a runoff; Cisneros and Cuellar were virtually even, with both of them falling below the 50 percent threshold for an outright victory, thanks to the votes won by a third candidate.

In her speech to supporters, Cisneros acknowledged that she didn’t expect final results till Wednesday. But she still claimed a sort of victory: “When I announced my first run in 2019, people told me this wasn’t possible.” But after the young human rights attorney lost in 2020 by fewer than four percentage points, no one made the mistake of not taking her seriously in this year’s rematch with Cuellar, and Cisneros demonstrated that she has a serious community movement behind her. “We are showing that our dreams can compete neck and neck,” she said. “We’re going to prove that we, as a people, are more powerful than any kind of money that they put their faith in.”

Even as the results got closer Tuesday night, Cisneros supporters remained elated. For her family and supporters, used to playing catchup to Cuellar, seeing Cisneros’s name first in the vote total had people beaming, even if it’s not the final result. As the clock reached midnight, Cisneros’s communications director took the stage and said, sheepishly, “They’re going to charge us more for the venue if we don’t leave now.” The room was still full, but folks laughed good-naturedly and began filing out. There wouldn’t be any victory speeches tonight.

Ken Paxton and George P. Bush Will Face Each Other in a Runoff

Forrest Wilder, 11:50 p.m.

In one of the marquee races of the night, we have a pair of winners—and a couple of also-rans. Texas attorney general Ken Paxton is headed to a runoff with land commissioner George P. Bush to decide who will run as the Republican nominee for Texas AG in the fall. With 86 percent of the vote counted, Paxton collected 43 percent of the vote to Bush’s 22 percent. For much of the night, Bush and Eva Guzman, the former Texas Supreme Court justice backed by much of the Big Business establishment in Texas, were neck and neck, vying for who would get the honor of taking on Paxton in what is sure to be a bruising, low-turnout May runoff. But Bush was able to gain the edge, in part by besting Guzman in the Rio Grande Valley, Dallas, El Paso, San Antonio, Fort Worth, and some suburban counties such as Collin, near Dallas, and Williamson, near Austin. In recent weeks Paxton previewed how he would run against Bush in a runoff: by calling him an establishment tool who feels entitled to higher office as part of the family dynasty. Paxton will sell himself as the true happy conservative warrior—the guy whose record of owning the libs and supporting Trump is untarnished. Those criminal charges? The work of the establishment, the same establishment that loves Bush so much. Did I mention that Trump endorsed me, not Bush?

Bush, for his part, told the press this evening that he plans to consolidate support from Guzman and Louie Gohmert, who came in fourth with around 17 percent, as well as the big-money backers who funded Guzman. Bush will keep hammering Paxton as damaged goods, a ripe target for Joe Biden’s Justice Department to drop an indictment on him around the time the general election campaign is revving up in late summer.

It’s hard to predict what will happen in a runoff, and it’s no doubt possible that Bush can beat Paxton. But Paxton’s 43 percent plus currently-in-fourth-place challenger Louie Gohmert’s 17 percent makes 60 percent, and it’s a little hard to imagine Gohmert voters breaking for Bush over Paxton in large numbers. Even so, this will be the biggest race in Texas in the next few months—expect a brawl.

Trump-Endorsed Republicans Run the Table

Michael Hardy, 11:32 p.m.

Trump made endorsements in 33 Texas races this cycle, from the governor’s race down to Tarrant County district attorney, and he’s currently batting close to a thousand. By Texas Monthly’s calculation, no candidate who received Trump’s endorsement has lost, and only five have been forced into runoffs—Attorney General Ken Paxton, land commissioner candidate Dawn Buckingham, state senator candidates Pete Flores and Frederick Frazier, and Tarrant County district attorney hopeful Phil Sorrells. All five Trump-approved candidates headed for runoffs won a plurality of the vote, and will likely be favorites to win outright.

Of course, when you mainly endorse incumbents, as Trump did, you’re likely to maintain a good track record. Trump endorsed 16 of 21 Texas Republicans running for reelection to Congress, and two candidates for open seats. (Four of the five incumbents he snubbed happen to have voted to certify Joe Biden’s election.) At the time of publication, every congressional candidate he endorsed appears to have won their nomination outright.

Does (Alleged) Crime Pay in Texas Elections?

Forrest Wilder, 11:10 p.m.

A Republican consultant recently told me that one of the megatrends in politics in recent years is that voters, both Republicans and Democrats, care less about scandals and wrongdoing, up to and including criminal activity, than in more settled times. This year’s Texas primaries seem to confirm that. Attorney General Ken Paxton, under indictment and dealing with enough alleged crimes to keep a mob lawyer busy, is comfortably on his way to a runoff. Already, at his victory party, Paxton is telling supporters that the runoff is all about taking on “the establishment”—he’s directly referring to George P. Bush, his likely runoff opponent, but also no doubt the deep state agents attacking Paxton and the conservative movement.

On the Democratic side, conservative Laredo congressman Henry Cuellar is almost certainly headed to a runoff with progressive challenger Jessica Cisneros. That’s not the best-case scenario for Cuellar, but keep in mind that it was just a weeks ago that the FBI raided his Laredo home in connection with an investigation into nonprofits and companies with ties to the state-owned oil company of Azerbaijan. Cuellar has not been charged with anything and has denied wrongdoing, and details about the grand jury probe are scarce. Nonetheless, voters weren’t moved enough by at least the suggestion of impropriety to change representatives. Meanwhile, state representative Ron Reynolds, a Houston Democrat, just cruised to another term after winning reelection in 2018 while serving a four-month stint in jail following a conviction for “ambulance chasing for profit.” Reynolds crushed his Democratic opponent by an 85–15 margin.

And finally there’s Justin Berry, an Austin-area Republican and Austin police officer who is one of 19 APD officers to be indicted recently for allegedly using excessive force on BLM protesters in 2020. He’s on his way to a runoff in the deep red House District 19.

Harris County Struggles to Count Votes—Once Again

Michael Hardy, 11:01 p.m.

With more than 4.7 million residents spread out across nearly 1,800 square miles, it’s not surprising that it takes time to count votes in Harris County. But should it really take this long? Election after election, the greater Houston area is one of the last parts of Texas to report its votes. Four hours after polls closed, Harris County elections administrator Isabel Longoria’s office has just started releasing a trickle of Election Day results. That leaves reporters to rely on early voting numbers, which represent around 50 percent of the expected vote totals. Without knowing how Houston voted on Election Day, it’s hard to determine who won close statewide races, let alone countywide positions.

Shortly after polls closed this evening, Texas Secretary of State John Scott released a statement claiming that Harris County officials couldn’t commit to counting all the votes by Wednesday at 7 p.m.—the deadline set by state law. According to the statement, the delays result from “damaged ballot sheets that must be duplicated before they can be scanned by ballot tabulators”—a reference to Harris County’s cumbersome new paper-based voting system. Scott publicly offered his office’s help

For years, Texas political junkies heaped scorn on former Harris County clerk Stan Stanart’s sluggish vote reporting. The hashtag #firestanstanart showed up in Twitter feeds every election night. But after Stanart lost reelection in 2018, the problems continued. Then-interim county clerk Chris Hollins won widespread praise for his brief stint overseeing the 2020 election, but after his tenure the Harris County Commissioners’ Court removed authority for conducting elections from the elected clerk and gave it to the newly created position of elections administrator. The commissioners appointed then-32-year-old Isabella Longoria, who formerly served as a special voting rights adviser to the county clerk.

The Harris County elections administration did not immediately respond to Texas Monthly’s request for an explanation for the delayed reporting.

Who Will Make the Runoff Against Ken Paxton?

Ben Rowen, 10:54 p.m.

As expected, Ken Paxton is heading to a runoff for the GOP nomination for attorney general. The question of who his opponent will be remains, though things are getting a bit clearer. With around 80 percent of ballots counted, George P. Bush is currently in second place with 22 percent of the vote, to Eva Guzman’s 18.

Louderback Rides Into the Sunset

Michael Hardy, 10:30 p.m.

A.J. Louderback just learned that winning a seat in Congress is a whole lot harder than getting elected small-town sheriff. The five-term lawman in Jackson County never faced serious political opposition until he decided to challenge incumbent Michael Cloud, a Trump-endorsed businessman who just won the primary in the southeast Texas district with 73.1 percent of the vote. Louderback, who attempted to out-MAGA Cloud with hard-line rhetoric about guns and immigration, limped into second place with just over 11 percent of the vote. Louderback stepped down as sheriff in December to challenge Cloud in the Twenty-seventh Congressional District, which stretches from Corpus Christi to the outer Houston suburbs.

Checking In on the World’s Second Greatest Deliberative Body

Christopher Hooks, 10:20 p.m.

In Texas House District 79, northeast of El Paso, state representatives Art Fierro and Claudia Ordaz Perez were pushed into the same race by redistricting. Democrats took sides. Fierro, who returned early from last year’s quorum break, was endorsed by state representative Joe Moody, the ranking Democrat in the House, who also returned early. Ordaz Perez was endorsed by Democrats who stayed. It wasn’t close—Ordaz Perez is winning, 67 to 33 percent.

Shelley Luther, the COVID cause célèbre who was briefly jailed in May 2020 for violating Governor Greg Abbott’s executive orders requiring that hair salons stay closed, ran this year in House District 62, against incumbent Reggie Smith. She once again won fame when she got tongue-tied and appeared to object to the principle that trans children shouldn’t be bullied in schools. This did not work, and Smith is beating Luther by twenty points.

In Harris County, Voters Judge the Judges

Michael Hardy, 10:11 p.m.

The all-Democratic slate of Harris County criminal court judges has been under sustained attack by District Attorney Kim Ogg, who accuses them of letting too many people out of jail on low bonds. The attacks seem to have made a difference—at the moment, at least half a dozen incumbent judges are losing their primary races. (With the caveat that, thanks to delays in reporting from the Harris County election administration, Election Day votes haven’t yet been counted—a bit over 50 percent of the total is in.) In the race for the 184th District Court, for instance, incumbent Abigail Anastasio is well behind challenger Katherine Thomas, an assistant district attorney under DA Ogg. Thomas is just one of the fourteen Ogg prosecutors who are running for Harris County judgeships this year. We’ll be watching to see how many of them advance to the general election in November.

Let’s Talk About South Texas Turnout Real Quick

Dan Solomon, 10:03 p.m.

One of the big stories out of 2020 was the GOP growth in South Texas. While we won’t know if that was an outlier or the start of a trend until we have more data—i.e., until November and beyond—one piece of information that might be worth noting is that throughout South Texas and the Rio Grande Valley, turnout on the Democratic primary ballot eclipsed that on the GOP side.

This is most striking in the Fifteenth Congressional District, which was redrawn into a “lean Republican” seat according to the Cook Political Report. In the GOP’s big pickup hope, with rising star Republican Monica De La Cruz on the ballot (she’s doing great, incidentally, running well ahead of a runoff), Democratic primary voters outnumbered Republicans 20,000 to 16,000. The 25 percent advantage among Democrats in the Fifteenth is dwarfed by the ones in the Twenty-eighth (24,000 to 13,000) and the deeper blueThirty-fourth (29,000 to 10,000). Primary turnout doesn’t correlate directly to general election turnout, of course—but if you’re looking for a new data point as you try to make sense of what exactly is going on in South Texas, the turnout advantage among Dems tonight is one to keep in mind as you make your predictions.

Houston Remembers George P. Bush’s Hurricane Harvey Debacle

Christopher Hooks, 9:58 p.m.

The most important outstanding question tonight, on the statewide ballot, is who will accompany Attorney General Ken Paxton into his Republican primary runoff: George P. Bush or Eva Guzman? With about three-fourths of the vote in, Paxton is sitting at 42.5 percent. Bush is pulling 21.5 percent, while Guzman is winning 19.5 percent. Guzman and Bush have been trading places most of the night. Bush is outperforming Guzman in South Texas, where his campaign has focused. Guzman is performing a bit better in cities. In Dallas and Tarrant Counties, Bush and Guzman are about even—in Travis and Bexar counties, Guzman is a few points ahead.

But in Harris County, the largest pool of votes in the state, Bush is getting trounced by Guzman two to one. There was a lot of anger in Houston over the way Bush’s office handled Harvey relief money, with many feeling the city had been shafted. He probably regrets that tonight—but he may squeak past Guzman regardless.

CD-8’s Lone Survivor

Michael Hardy, 9:52 p.m.

Several hundred people have gathered at Honor Cafe in the Houston suburb of Conroe for congressional candidate Morgan Luttrell’s election watch party. With about 80 percent of the votes counted, Luttrell, a retired Navy SEAL, currently leads the field of eleven candidates with 53 percent—enough to avoid a runoff in the race for the Eighth Congressional District. The next highest vote-getter, with 22 percent, is Christian Collins, a political operative endorsed by Ted Cruz, Marjorie Taylor Greene, and much of the far-right House Freedom Caucus. Jonathan Hullihan, a Navy JAG attorney who has positioned himself even further to the right, is in third with 12 percent.

Several Luttrell supporters told me they were turned off by Collins’s campaign mailers calling Luttrell a RINO (Republican in Name Only). “People who know Luttrell and his character just threw those in the trash,” said Teresa Poore, a booking agent for Team Never Quit—a veteran-focused speakers bureau that represents Luttrell’s brother Marcus, a fellow Navy SEAL and the inspiration for the film Lone Survivor. “He thinks for himself. He’s not going to be a puppet.”

Given his high-profile supporters, Collins’s failing to make the runoff would be a major blow. But it’s a victory for U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, who backed Luttrell with funding from a super PAC associated with the House leadership. Given the congressional district’s deep-red voting record, Luttrell is practically a shoo-in against Democratic nominee Laura Jones, who ran unopposed.

“Collins was too negative with the mailers,” another Luttrell supporter, who declined to give his name, told me. “Luttrell is more focused on the issues rather than attacking people.”

The Democratic Race for Land Commissioner Is a Crapshoot

Forrest Wilder, 9:44 p.m.

Another Democratic primary, another set of somewhat random results. It’s too early to call a lot of the statewide races—Beto’s overwhelming victory in the governor’s race aside—but it’s not too early to scratch our heads over some of the results. Take a look at the four-way race for land commissioner. At present, licensed therapist Sandragrace Martinez is leading with 30.6 percent of the vote followed by conservationist Jay Kleberg (27.7 percent), followed by Jinny Suh (21.4 percent), followed by Michael Lange (20.3 percent).

Statistically, this is not too far away from an equal split among the candidates—a result that could, one might argue, be the result of essentially a coin flip among voters. The current front-runner is an unknown in Texas politics who raised just a few thousand bucks. Ditto for Michael Lange. Suh is also an unknown but raised a more respectable—if we’re being generous—$76,000 or so. Only Kleberg, a scion of the King Ranch, can be said to have anything like name recognition or the kind of cash one needs to mount a statewide campaign. And yet he will be counting his blessings just to make a runoff.

The GOP Railroad Commissioner Race Is Taking a Surprising Turn

Russell Gold, 9:36 p.m.

It looks like it’s the Grammy-nominated, gospel-singing septuagenarian incumbent versus the millennial, social media–savvy, pasty-wearing lawyer in a runoff to remember. In the GOP railroad commissioner race, it appears that incumbent Wayne Christian will not have enough votes to win outright and is heading to a runoff against Sarah Stogner.

Meanwhile, neither has as many votes as . . . Democrat Luke Warford received in the Democratic primary? Okay, okay, before you start thinking Texas is turning purple, it’s worth noting that he didn’t have anyone running against him—and there were five Republicans splitting the vote in the other primary.

Is Jessica Cisneros Heading to Victory—Or to a Runoff?

Jack Herrera, 9:10 p.m.

Two years ago, powerful congressman Henry Cuellar held off a Democratic primary challenge from progressive human-rights lawyer Jessica Cisneros, prevailing by less than 4 percent. In the rematch, it appears that Cisneros could be on her way to unseating the incumbent—or to a runoff with him. With roughly half the votes counted, she has barely more than 50 percent of the vote, with Cuellar at 45—and a third candidate, progressive lawyer Tannya Benavides, at 4.6 percent.

In Bexar County, which includes San Antonio, Cisneros has a commanding lead—more than her margin in 2020 there. But Cuellar leads in Webb County, home to Laredo—also besting his 2020 margin. More than 70 percent of the vote has been counted in both counties.

Cuellar had seemed likely to win again this year until his campaign was hobbled by an FBI raid on his home and campaign office in late January, as part of a wide-ranging probe into a group of U.S. businessmen and the government of Azerbaijan. Though Cuellar has not been indicted—and says the investigation will clear him of any suspicion—the raid nonetheless gave new life to Cisneros’s second bid, driving home the perception some voters have of Cuellar as corrupt.

Beto O’Rourke’s Inevitable Primary Victory

Christopher Hooks, 8:52 p.m.

No surprise here, but Beto O’Rourke is cruising to the Democratic nomination for governor with 92 percent of the vote. In 2018, O’Rourke ran into trouble in his primary for the U.S. Senate nomination, winning only 62 percent of the vote and losing many counties outright in South Texas. This time, though, Democratic voters seem to be familiar with him.

Greg Casar, a Democratic Socialist, Has Won His U.S. House Primary

Dan Solomon, 8:48 p.m.

Though a snafu with the Travis County vote count kept the celebration on ice for a while, when the results came in, there was little doubt about who had won in the Thirty-fifth Congressional District: Greg Casar. Around 8:10 tonight, former Austin city councilman Casar took the stage at Austin bar Native Hostel to declare victory—without a runoff—over his three opponents. Casar took 71 percent of the vote in his hometown, which comprises the largest share of the voters. Combine that with a fifteen-point lead in Bexar County over his closest challenger, and the math was clearly in Casar’s favor.

The 32-year-old democratic socialist immediately becomes the presumptive next representative in one of the state’s most reliably blue districts, which only deepened the celebratory air of the watch party. Supporters and volunteers sipped hard cider on the gravel patio next to I-35 alongside Austin political figures—Mayor Steve Adler among them—while Casar snapped celebratory selfies. Up next? Likely a frustrating spell in the minority if the GOP takes the House. But for tonight, at least, Casar and his supporters are all smiles.

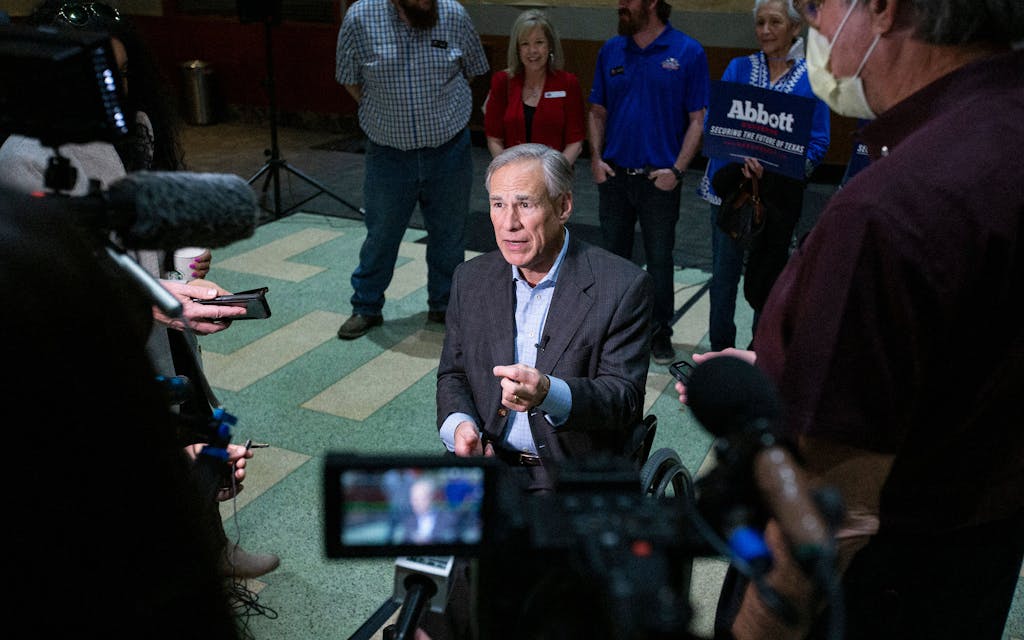

Greg Abbott Wins the GOP Nomination Outright and Avoids a Runoff

Christopher Hooks, 8:36

Greg Abbott has clinched renomination, and despite several years of anger from the right, it wasn’t much of a fight. With a little more than half the votes counted, Abbott has 69 percent of the vote. His two main challengers—libertarian Don Huffines and tea party hero Allen West—performed absolutely dismally, each pulling in about 11 percent of the vote. (The False Rick Perry, a man from Springtown—not the former governor—is winning only 3 percent, while Baroness Kandy Kaye Horn is winning only 1 percent, proof that Texas voters don’t know what’s good for them.)

The biggest political story in the state for much of the pandemic was how angry right-wing voters were with Abbott over COVID restrictions. They were extremely loud. And there weren’t, evidently, very many of them. Haters may hate, but Abbott abides.

Robert Morrow Doffs His Jester Cap Once More to State Board of Education District 5

Dan Solomon, 8:22 p.m.

Perennial candidate (and occasional election-winner) Robert Morrow—whom voters may recall from his habit of wearing a jester’s cap to Travis County GOP meetings when he was somehow elected party chair, or perhaps for his undying affection for tweeting improbable anime boobs—is once more on the ballot, and once more doing pretty well. This year he’s running for the GOP nomination for a State Board of Education seat in an Austin-based district against physics PhD and textbook author Mark Loewe, and has received 49 percent of the vote so far, with 17 percent of ballots counted. Why? Who knows! Morrow doesn’t really have a constituency, but also voters don’t often know who the candidates are in primary races for positions like State Board of Education.

Even if Morrow prevails here, he is likely to lose the seat to Democratic incumbent Rebecca Bell-Metereau—but if you’re a fan of grown men who are just proudly who they are spending time in the public eye, there’s a real possibility you’ve got eight more months of Robert Morrow in your life.

Sid Miller Looks Likely to Survive

Christopher Hooks, 8:08 p.m.

Too early to call, but it certainly looks like state representative James White’s primary challenge to agriculture commissioner Sid Miller has failed. With about 20 percent of the vote in, Miller is winning about 60 percent of the vote to White’s 30. The main threat left to Miller, who has become Texas’s chief poster of memes in his eight years in office, is that he dips below 50 and then has to fight a runoff.

If Miller wins, he’ll continue to face a hostile Legislature and Republican establishment—while a felony corruption trial for his former top aide draws nearer. White, meanwhile, will be missed in the Legislature. Though a staunch conservative, he was respected by lawmakers from both sides of the aisle, and his voice on criminal justice issues could be helpful in breaking gridlock on reforms.

Don Huffines Claims Moral (But Not Political) Victory

Ben Rowen, 7:59 p.m.

It’s early, but with nearly a third of the vote counted, Greg Abbott is winning nearly 70 percent of the vote, comfortably above the threshold to avoid a runoff. In second place with just more than 12 percent of the vote is Don Huffines, who has already offered what passes for concession remarks these days, tweeting, “For over a year our campaign has driven the narrative in Texas and forced Greg Abbott to deliver real conservative victories. . . .”

It’s a remarkable change in tone from when we spoke after a campaign event in Dripping Springs in January. I had asked Huffines if he considered it a victory just having pushed Abbott right on issues including abortion, permitless carry of firearms, and vaccine mandates. “Yeah, sure, it’s a win, but it’s not enough of a win,” he said. “It’s just not. Abbott is a political windsock. So he’ll go back the other way, and he’s just going to pivot wherever the political winds are blowing.”

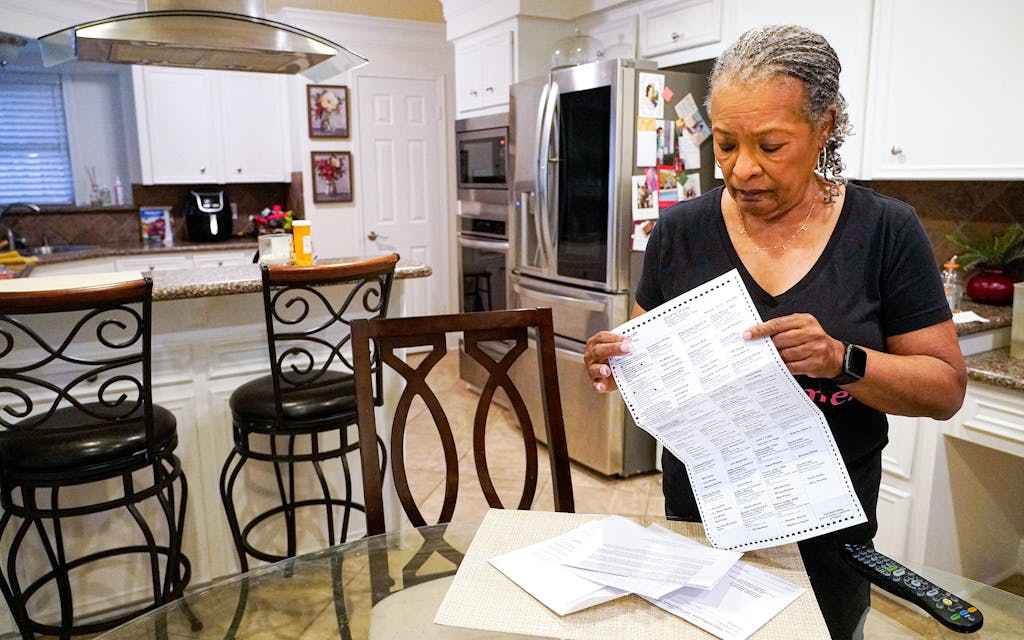

Welcome to the Texas Voting Obstacle Course

Michael Hardy, 7:24 p.m.

All day, social media was filled with accounts of Texas voters frustrated by our byzantine new election law. Senate Bill 1, passed by the GOP-dominated Legislature last year, has turned requesting an absentee ballot into an elaborate game in which voters must remember what form of ID they used to register to vote, then write that number in the correct spot on the envelope they mail in. As of February 18, the state’s most populous counties had rejected around 10 percent of absentee ballot applications. In Harris County, that number was 30 percent.

Even someone as politically savvy as former Houston mayor Annise Parker got tripped up by the process. Parker, her wife, and her mother are all over 65 and traditionally vote by mail. They successfully requested paper ballots, but after mailing them in, Parker and her mother learned that theirs had been rejected because they failed to write their ID numbers in the correct place. They managed to submit new ballots, which they hope will arrive by the deadline of tomorrow. Parker’s wife’s ballot was also rejected, but she found out too late to correct it by mail. When she attempted to vote in person today she was turned away, Parker told me.

“[SB 1] has taken a straightforward process that is extremely beneficial to voters and made it much more difficult, for no apparent reason,” Parker said. “This is a completely unnecessary law. I think the initial target is Democratic voters, minority voters, but over time it will have a disproportionate impact on others as well, because so many elderly voters are Republican.”

Amber Kimbrell, a farmer in rural Moore County, north of Amarillo, blames SB 1 for her own voting problems. Two weeks ago she received a letter from her county election administrator asking her to prove that she lives at the address on her voter registration form. Kimbrell, who has lived at her address for more than fifteen years, couldn’t understand why she received the letter—after all, her husband lives at the same address, and he didn’t receive a letter. Kimbrell contacted the election office and confirmed her address, but the experience has shaken her faith in the state’s voting laws.

“I hope my vote counted, but I have no way to prove that it counted,” she told me. When I asked why she thought she received the letter, she didn’t hesitate. “I don’t think Greg Abbott wants me to vote. That’s what I honestly think.”

Checking In on Van Taylor and the “Big Lie” Primary

Forrest Wilder, 7:13 p.m.

Earlier today, I wrote about how “Stop the Steal” messaging is animating one primary in North Texas. We now have early results from Collin County in the race. If this holds, Taylor could narrowly avoid a runoff, but there are still lots of votes to count.

The Panic That The Kids Are Not Alright

Christopher Hooks, 6:59 p.m.

Texas primary elections of all kinds often hinge on issues that are kind of irrelevant, but the parties chase irrelevancy in different ways. Democrats love to talk up policies they’ll never in a hundred years have the political power to implement. Republican partisans, meanwhile, find the most minute differences possible between each other—the one thing that didn’t go right out of ten things that did, on an issue most people could hardly find the energy to care about—and beat each other half to death with them. There’s an imbalance here that colors everything else. Democrats are out of power and need to look serious, while Republicans have all the power and so don’t need to look serious.

This has been a traumatic and difficult few years for Texans of all stripes. The terrible economic collapse of 2020 was mended, but the economy remains shaky, with the cost of living spiking around Texas, particularly in cities that have become overwhelmed with growth. A little more than a year ago, Texas saw the worst man-made disaster in its history, which killed more than seven hundred people, and which was caused largely by greed and the incompetence of state government. A pandemic, which was much more fatal here than in peer states such as California, exposed severe weaknesses in the state’s health care system and social safety net. And while left and right fought over the state’s COVID restrictions in debates that were usually louder than they were wise, the pandemic raised real questions about the governor’s authority to implement his emergency orders. What does it mean to give the executive sweeping powers in a state in which legislators, the only ones who can check him, are mandated to meet for only five months out of every twenty-four?

Naturally, debates in the GOP primary skirted most of these questions—even the question of what to do about Abbott’s executive power, on which Republicans have a substantive case to make. Instead, we talked about—most of all—the children.

The tone of the primary was set by former representative and current candidate for Tarrant County DA Matt Krause, who in October released a list of 850 books in school libraries that “might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex.” He wanted to get rid of them. Life is discomfort, of course. Psychological distress is the price we pay for living. In Fun With Dick and Jane, we are confronted by the troubling realization that, though we are all human, the duality of sex means that we can never truly understand one another—we will be forever apart. That book is not on Krause’s list, but a bunch of books about how Black people got a raw deal in America were.

The moral panic about children took on a seedier, grubbier, more menacing tone as time went on. Following the last Lege, grassroots conservatives were very mad that leaders had not acted more aggressively to stop the “genital mutilation” of children, which is what they call treatments given to some children that identify as transgender—mostly hormone therapy. They didn’t get the bill they wanted, and they stayed mad. So, in the past few weeks Ken Paxton and Greg Abbott, who both need to avoid a runoff, took bold action. Last week, Abbott ordered state agencies to investigate the parents of trans children for child abuse, weeks after Texas attorney general Ken Paxton issued an opinion that gender affirming care for children is such. Today, it was announced that the first investigation had begun—and that the mother targeted worked at the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, where her job was to investigate reports of abuse and neglect. The anguish of a few families is a small cost to pay to help the governor make extra-extra sure he avoids a runoff, surely.

Man Versus Machine at a Houston Polling Place

Michael Hardy, 6:45 p.m

Last year, Harris County, home to Houston, replaced its twenty-year-old voting machines with new touchscreen devices that produce a paper record, allowing a more rigorous audit of election results. But voters have struggled to adapt to the cumbersome new system. Produced by Hart InterCivic, the new machines require voters to feed two pieces of paper into a slot, make their votes on a computer monitor, then hit print. After verifying that they selected the right candidates, voters then insert the paper ballots into a second machine to be scanned.

At the Korean Central Presbyterian Church in west Houston, Democratic precinct judge Demi Stein told me that the machines had been causing problems all day. “The paper jams are rough,” she said. In one case, a printer malfunctioned, smearing ink so badly that it made the ballot illegible. The voter had to be issued a provisional ballot. Stein’s Republican counterpart, Beverly Batho, also expressed frustration. “The voting machines are extraordinarily temperamental with the paper,” Batho said. “Voters have to put the paper in properly.” Around ten voters at the precinct cast provisional ballots this afternoon because of machine malfunctions.

Former Houston mayor Annise Parker told me that she was glad Houston now has a paper-based voting system, which she said was more secure than the previous digital-only machines. “But apparently the clerks don’t know how to use them appropriately,” Parker said. “And the machines themselves are a little glitchy, so it’s a very slow process.”

At least access wasn’t a problem. When I visited the precinct at around 3 p.m, there was no line and there were plenty of empty voting booths. “There were four or five people waiting to vote at 7 a.m. [when polls opened], but since then it’s been flowing,” Stein told me.

The Front Line of the Battle Over Abortion in Texas Is a Democrat Versus Democrat Primary

Jack Herrera, 6:32 p.m.

With SB 8, the Texas “heartbeat” bill, making its way slowly through the court system, both pro-choice and anti-abortion organizations have thrown their energy—and money—into one key Democratic primary for Congress. In the Twenty-eighthDistrict, anchored in Laredo, the progressive human rights lawyer Jessica Cisneros is again trying to unseat nine-term Congressman Henry Cuellar, the “King of Laredo.” Abortion has become a key issue in the race, which could be decided today.

In January, the day before the anniversary of Roe v. Wade—and a few days after the FBI raided his house, as part of a wide-ranging probe into the activities of some U.S. businessman and the government of Azerbaijan—Cuellar accepted an award from March for Life, a major anti-abortion advocacy group. “It’s not only protecting the unborn, but it’s also protecting every life from womb to tomb. Your defense should be clear and firm and passionate,” the congressman said in his acceptance speech. Cuellar was the lone Democrat in the U.S. House to vote against the Women’s Health Protection Act, legislation designed to override SB 8. “It’s called conscience,” Cuellar told reporters after the vote. “I am a Catholic, and I do believe in rights, [and] right to life.”

“Despite being under an FBI investigation, Henry Cuellar has once again proven that nothing can stop him from opposing our reproductive rights and freedoms,” Cisneros said in a statement shared with Texas Monthly in January. A strong pro-choice campaigner, Cisneros has received backing from pro–abortion rights organizations from across the country, including the prominent group NARAL, which sent five of its own staff to South Texas to drum up votes for Cisneros. NARAL, which also endorsed Cisneros in 2020, has labeled Cuellar “the last anti-choice Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives.”

The Twenty-eighth District, overwhelmingly Hispanic and largely Catholic, has historically been reliably anti-abortion. But as a younger, more progressive generation has come of age, that could be changing. This race will be, in part, a referendum on the issue.

Trump’s “Complete and Total” Texas Endorsements

Michael Hardy, 6:13 p.m.

Former president Donald Trump has endorsed 33 candidates in the Texas Republican primary, including federal, state, and county candidates. Given Trump’s massive popularity in the state GOP, candidates have assiduously courted his endorsement. (A February UT-Austin poll found that 80 percent of Texas Republicans have a “very favorable” or “somewhat favorable view” of Trump.) The state’s top incumbents—Greg Abbott, Dan Patrick, and Ken Paxton—have all received Trump’s blessing. Such is Trump’s power that even candidates who failed to secure a nod, such as Congressman Louie Gohmert, who is challenging Paxton for attorney general, have touted Trump’s support. Gohmert has claimed that Trump only endorsed Paxton because the former president didn’t think Gohmert would run. Republican candidates up and down the ballot have positioned themselves as the true MAGA candidates, even if Trump happens to be backing someone else.

Patrick, who served as state chair of Trump’s two presidential campaigns, appears to be the driving force behind Trump’s endorsements. Notably, the former president has snubbed the four GOP congressmen who voted in January to certify President Joe Biden’s victory (Van Taylor, Chip Roy, Dan Crenshaw, and Tony Gonzales), although Trump hasn’t endorsed any of their challengers. In some close races, such as the Morgan Luttrell and Christian Collins showdown in the Eighth Congressional District, Trump appears to be waiting until a likely runoff before picking a candidate. We’ll be watching to see how many of Trump’s favored Texas candidates win tonight.

Back the Red

Forrest Wilder, 6:00 p.m.

There seems to be an unusual number of law enforcement officials running for office this cycle, perhaps a reflection of the popularity of the “Blue Lives Matter” movement on the right and the centrality of a law and order message. Texas Monthly identified 22 candidates on the ballot with law enforcement ties—17 Republicans and 5 Democrats—including ten current or former police officers, five former or current sheriffs or sheriff’s deputies, and two Border Patrol agents. The rest represent a mix of local, state, and federal peace officers.

Several are incumbents running for reelection or running for higher office, including former Fort Bend County sheriff Troy Nehls and state representative Phil King, who’s angling for a state Senate seat in North Texas. One of the most promising pickups for cop candidates lies in House District 61, a Collin County conservative stronghold, where Paul Chabot, a former military intelligence officer and deputy sheriff who moved to Texas from California in 2016 and now runs Conservative Move, faces Frederick Frazier, a former Dallas police officer and chairman of the Dallas Police Association PAC.

In Central Texas, Austin police officer Justin Berry, along with three other Republican contenders, is running to represent a chunk of West Austin and the Hill Country. Will Republican voters care that Berry is one of nineteen APD officers recently indicted for allegedly using excessive force on protesters during the BLM protests of 2020? Chances are it will help him. We’re also keeping an eye on former Jackson County sheriff A.J. Louderback, a frequent Fox News guest who is challenging right-wing Congressman Michael Cloud from the outer fringes of Trumplandia. And Willie Vasquez Ng, a retired San Antonio cop, is running in the crowded primary for the Twenty-eighth Congressional District, the San Antonio-to-Laredo district represented by “King of Laredo” Henry Cuellar. According to Patrick Svitek of the Texas Tribune, a pro-police PAC, Protect and Serve, spent more than $200,000 on a media buy for Vasquez Ng in the past week.

The Attorney General’s Race and Texas’s Attack on Trans Kids

Dan Solomon, 5:41 p.m.

One big piece of news today that isn’t election-related: a family is now under investigation for pursuing medical care for a trans child. Last week, Governor Greg Abbott sent a letter instructing the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services to investigate parents who pursue medical treatment for their transgender children as potential child abusers. There’s plenty to say about that outside of an election-night live blog, but one part of it that does overlap with what’s happening at the polls today is that the order is the result not of a new Texas law, but of the opinion of Texas attorney general Ken Paxton that medical treatments such as puberty blockers are “child abuse”—and his name appears on the ballot today.

It’s unclear if any of Paxton’s GOP primary opponents would have issued a similar legal opinion on the matter, though at a debate earlier in the month, all three said they agreed with the substance of Paxton’s opinion. What’s clear is that if any of the candidates on the Democratic ballot wins the office, they’ll approach the issue with a vastly different legal opinion. Mike Fields, running for the office as a Democrat, raised the issue in an interview last week. “LGBTQ adults and children need to be protected from violence and administrative overreach that goes into their health decisions,” he said. If he—or Rochelle Garza, Joe Jaworski, or Lee Merritt, who agree with him on the matter—ends up in office, we’ll learn quickly if Abbott still believes that the AG’s opinion should be enforced as though it’s law.

The Texas Legislature and Local Races

Republicans Fight for Relevance in Harris County

Michael Hardy, 5:22 p.m.

No Republican has won a countywide race in Harris County since 2014, but the local GOP is praying that a wave election in November will end their losing streak. First, though, they have to pick candidates to go up against the all-Democrat slate of incumbents. The biggest target is Lina Hidalgo, the county’s top executive, who upset moderate Republican Ed Emmett in 2018 and has generated Republican enmity with her progressive rhetoric and COVID-19 health measures. No fewer than nine candidates are vying for the chance to go up against Hidalgo, the strongest of whom appear to be Mattress Mack–endorsed retired Army captain Alexandra del Moral Mealer and Dan Crenshaw–endorsed attorney Vidal Martinez.

We’re also watching the normally sleepy judicial races, which have been roiled by controversy over bail reform and rising homicides. Fourteen prosecutors from the office of District Attorney Kim Ogg, who has repeatedly criticized sitting judges for setting low bail, are challenging the slate of progressive criminal court judges.

Checking In on Our 2021 Worst Legislators

Ben Rowen, 5:15 p.m.

Last year, we picked a group of ten legislators (well eight legislators, the lieutenant governor, and one full caucus) for our biennial Worst list. For some, getting on the list is a badge of honor—a plaudit they can wave to their supporters as evidence that they must be doing something right, since the “fake news media” disparages them. For example, the day we posted the 2021 list online, Briscoe Cain—a representative from Deer Park, in the Houston outskirts, who had fumbled a major bill he was tasked with handling—posted on his official Facebook page that “he considered it an honor” and used the “award” as a promotional blurb.

Taking a look at the reelection chances of the Worsts reveals, unsurprisingly, that Texas Monthly’s vote of no confidence has not swayed the masses (you can read the list, and the reasons for each legislator’s selection, here):

Senators Charles Perry (R-Lubbock) and Bryan Hughes (R-Mineola) are both running unopposed in the primary and general elections. Representative Briscoe Cain (R–Deer Park) and Senator Bob Hall (R-Edgewood), meanwhile, are running unopposed in the primary, but will each face a Democratic challenger in November.

Representative Kyle Biedermman (R-Fredericksburg) is not seeking reelection. I wrote about the primary to fill his seat earlier today at 4:42 p.m. if you want to scroll all the way back.

The entire Senate Democratic caucus: Of the thirteen Senate Democrats, one, Eddie Lucio Jr., is retiring, and eleven will not face primary opposition (three of them will also not face a general election opponent). That leaves a single incumbent, John Whitmire of Houston—the dean of the Texas Senate—with a challenger. Whitmire has announced a 2023 bid to be Houston’s mayor; his primary opponent, Molly Cook, has hammered him for running for two offices at once.

Representative Harold Dutton Jr. (D-Houston) faces one primary challenger, Candis Houston, who is backed by a host of progressive groups including the AFL-CIO, Annie’s List, and a PAC called Texans for Better Democrats Coalition.

Representative Gary Gates (R-Richmond) is being primaried by Robert Boettcher, who serves on the Sugar Land Zoning Board and was a precinct chair for the Fort Bend County GOP. Boettcher’s been endorsed by the right-wing grassroots organization True Texas Project, a onetime kingmaker. Just as we did, Boettcher highlights two issues in his criticisms of Gates, a landlord. First, a bill he introduced to exempt landlords from building codes. And second, a bill he introduced to make it harder for Child Protective Services to accept anonymous tips.

Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick (R-Statewide) faces five primary opponents in his reelection bid, none of whom are registering in the polls. The most interesting races to follow involving Patrick are the legislative ones in which he’s endorsed. We’ll be tracking throughout the night how much success he has handpicking who will work with—or rather for—him in the Senate.

Representative Steve Toth (R–The Woodlands) faces one primary challenger, Maris Blair, an attorney and the executive director of the Conroe ISD Education Foundation. Blair, who does not have an issues page on her website, has attacked Toth for unsuccessfully suing Greg Abbott over a contact tracing contract and wasting “valuable time battling our conservative leaders.” Toth is endorsed by Ted Cruz, the NRA, and a host of right-wing grassroots groups—to whom his challenges of establishment Republicans are one of his greatest merits.

Texas House Republican Candidates Battle to Be the Most MAGA

Ben Rowen, 4:59 p.m.

In some primaries, candidates offer competing visions for their party (e.g. Should Democrats fight Republicans, or acquiesce to them to try to earn concessions? Should Republican lawmakers require natural gas producers to weatherize their facilities or not?). In others—most, perhaps—candidates offer the same vision, but maybe one is looking through Trump shades while the other prefers to see through red, white, and blue–tinted contacts. Here is one Texas House race we’re watching that’s the latter type, and one that’s the former.

House District 19 (Boerne, Burnet, Fredericksburg): Last year, we had a tough time selecting our “Worst Legislators”—there was an embarrassment of riches. One selection, however, was easy: Kyle Biedermann. The representative from Fredericksburg, eighty miles west of Austin, filed a bill to call for Texas secession, and he was near the U.S. Capitol steps on January 6 when rioters stormed the building. It seems Biedermann didn’t make many friends within his caucus, either: when the new state House maps came out, his district had been chopped into two. He declined to seek reelection in either.

In his stead, three candidates are vying for the seat. Austin police officer Justin Berry is running on a pro–law enforcement platform. He’s been indicted on charges that he used excessive force in 2020 during protests in the city over the murder of George Floyd—and some politicos believe that could help him in the primary. Meanwhile, most of the money in the race is behind former Austin City Council member Ellen Troxclair, who vows to block the creep of Austin values toward its ’burbs. Then there’s Nubia Devine, who three decades ago left Venezuela for Texas “as communism took hold.” Devine, who’s a former aide to a GOP Austin city councilman and the wife of Texas Supreme Court justice John Devine, is offering a standard 2022 GOP platform of securing the border, improving “election integrity,” and ending gender-affirming care for trans minors.

Biedermann, for his part, supports Devine. He told me in January, “I believe that Nubia Devine being Hispanic, and a woman, would be actually a better voice than I am in the Texas House floor, because there is not a single Hispanic woman in the Republican caucus. And I think that’s important—not because I believe in diversity, which is what people say. I believe [that] we, as you know, unfortunately, white males, we don’t really get a voice.”

House District 31 (Poteet, Falfurrias, Rio Grande City): Seven-term Democratic representative Ryan Guillen made headlines in November for switching parties and becoming a Republican. The move was likely a political necessity: along with the South Texas rightward shift in 2020, his district got thoroughly gerrymandered (Trump would have won it by 25 points had it existed in 2020). Guillen received a hero’s welcome in his new party. Donald Trump endorsed him, as did Greg Abbott and Speaker of the Texas House Dade Phelan. With the top of the party in line, and with the benefits of incumbency, Guillen is likely to prevail against his two challengers. But while the GOP leadership supports him, might some rank-and-file rightwing primary voters hold his former party affiliation against him? One challenger, Mike Monreal, is a Navy vet endorsed by several grassroots groups who pitches himself as a “man of courage” against Guillen’s “politician of convenience.” A second challenger, Alena Berlanga, is a Floresville ISD board member who was served arrest warrants last summer related to the theft of a donkey.

House Dems-els in Distress

Ben Rowen, 4:42 p.m.

A quick refresher on 2021’s budding of the perennial “Dems in disarray” flower: the party’s caucus in the Texas House was split last year on how to approach the thorny problem of having no power. Was it best to be accommodating and collegial with Republicans to try to earn marginal concessions, and ultimately get steamrolled? Or was it best to fight tooth and nail, delay, delay, delay, and ultimately get steamrolled? The two approaches came to a head with SB 1, the “election integrity” bill which most everyone in the Democratic caucus recognized as an attempt to make it harder to vote and to hurt their party’s chances of winning elections.

House Democrats dramatically walked out of the Capitol on the final night of the regular session, denying Republicans a quorum necessary to pass the bill—and then most in the caucus went to Washington, D.C., to continue denying a quorum in the first special session Abbott called. At the end of that special session, things got testy: some in the caucus decided to stay in D.C.; others came home, restoring a quorum for a second special session and ensuring that SB 1 would pass. Which brings us to two key primaries with candidates offering competing visions for the party:

House District 79 (El Paso): Two-term representative Art Fierro was in the first group of four House Democrats to return to Austin in August. His opponent, Claudia Ordaz Perez, a one-term representative who was subsequently redistricted into the Seventy-ninth, remained in D.C. She launched her campaign around Fierro’s decision to return. (Lawyers for Fierro lost a lawsuit challenging her eligibility to run in the district.) Joe Moody, the El Paso Democrat and Speaker pro tempore of the House who also returned to Austin with Fierro, has endorsed Fierro. Meanwhile, some representatives who remained in D.C., and the Texans for Better Democrats Coalition, a new progressive PAC, have endorsed Perez.

House District 114 (Dallas): “Opposition standard-bearer in the House … whose fiery conscience was matched only by his temper.” That’s how Paul Burka described John Bryant in his second consecutive selection as a Best in our 1977 ranking of legislators. After serving four terms, Bryant left for the U.S. House, where he served seven terms. Now, at 75, he’s running for state House again to replace retiring Democrat John Turner, compelled to reenter politics, Bryant says, because “Democrats are losing every single battle [and] it was time to step up and try to provide some leadership.” He faces four Democrats, all in their thirties, who, like him, promise to fight Republicans on voting rights issues. Questions abound about whether an old, white Democrat in a majority non-white district is the appropriate standard-bearer for the party. (Bryant does tout the endorsement of some “bald eagles of White Rock Lake” on his website, however).

The Imaginarium of Dan Patrick

Ben Rowen, 4:29 p.m.

Texas Legislature observers often pithily remark that the state Senate has only one member: so complete is Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick’s control of the body that mostly it does whatever he wants. But fresh off redistricting, there will be 31 senators elected this year. (They will then draw lots to determine who’s up again in two years, and who gets to serve a full four-year term). Nine candidates are running unopposed in both the primary and the general election, and in another eleven races there won’t be a primary contest for either party. In a state with new maps designed to limit interparty competition, that means there’s not much in the way of intrigue in the Senate. Of the eleven races with a Democratic or Republican primary, or both, here are two we’re watching:

GOP primary in Senate District 31 (Amarillo, Midland, Odessa): If the GOP caucus in the Texas Senate had a second member the last few sessions, it was Kel Seliger, from Amarillo. The “local control” advocate—who opposed state laws dictating how local governments could levy taxes—often sparred intellectually with Patrick, and occasionally would even vote against him, for which he was stripped of his committee chairmanships. Seliger’s district is a bizarre one to have produced a centrist (by Texas Lege standards) Republican: It was the most Trump-voting of all 31 state Senate districts. Nonetheless, in the fall, Seliger voted against a bill Donald Trump had called for that would have required a full audit of the 2020 election results. An hour later the former president endorsed Kevin Sparks, an oilman from Midland who’d announced a primary challenge, and shortly thereafter Seliger decided not to seek reelection.

Sparks now faces three other opponents in the primary: Stormy Bradley, a Coahoma ISD trustee and crusader against critical race theory; Tim Reid, a former FBI agent and local control advocate (it would somehow keep CRT out of schools, in his telling); and Jesse Quackenbush, a pro–wind energy attorney. With the endorsements of Trump, Patrick, Ted Cruz, Rick Perry, and countless other big-timers in state and national politics, it’s Spark’s race to lose. No Democrat has launched what would have been a quixotic bid, so if Sparks prevails tonight or in a May runoff, Dan Patrick will have completed his sweep of the Senate.