This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It was already the sort of day only a Houstonian could love—well into the nineties and humid—when Marie McGowen, a 62-year-old white woman, arrived at Massey Business College on the morning of July 9. She parked in her usual space in a lot behind the school, gathered up her purse and two bulky shopping bags, and walked to the back entrance. It was 7:15. Near the door she saw a pleasant-looking young black man who said, “Good morning.” She passed by him, but he followed, and as she got to the entrance, he hit her in the head with a brick. She sprawled on the sidewalk, bleeding profusely. The young man dragged her to some nearby bushes and then ran and got her car. He scattered her belongings, then stuffed Marie McGowen in the trunk. He drove around aimlessly, all over the city, for nearly four hours. At some point he stopped, pulled her out of the trunk, and raped her brutally enough to leave her undergarments soaked with blood.

Late that afternoon, when patrolling police officers found the abandoned vehicle in a desolate section of Houston near Hobby Airport, they called Marie McGowen’s husband to get a key to the trunk. While poking about the scene, he squatted down and looked underneath the car. He looked once, twice, before he recognized the body of his wife; she had been run over by her car.

It took all of a week to come up with a suspect. The fingerprints of Antonio Nathaniel Bonham, a 21-year-old ex-con, were found all over the car, and a set of keys found at Massey Business College turned out to fit doors in Bonham’s mother’s, father’s, and sister’s houses. When he was picked up for questioning, Bonham even confessed, at least partially. He admitted that he had kidnapped the woman and that he had “abused her,” but he said her death was an accident. He hadn’t meant to run over her on that road.

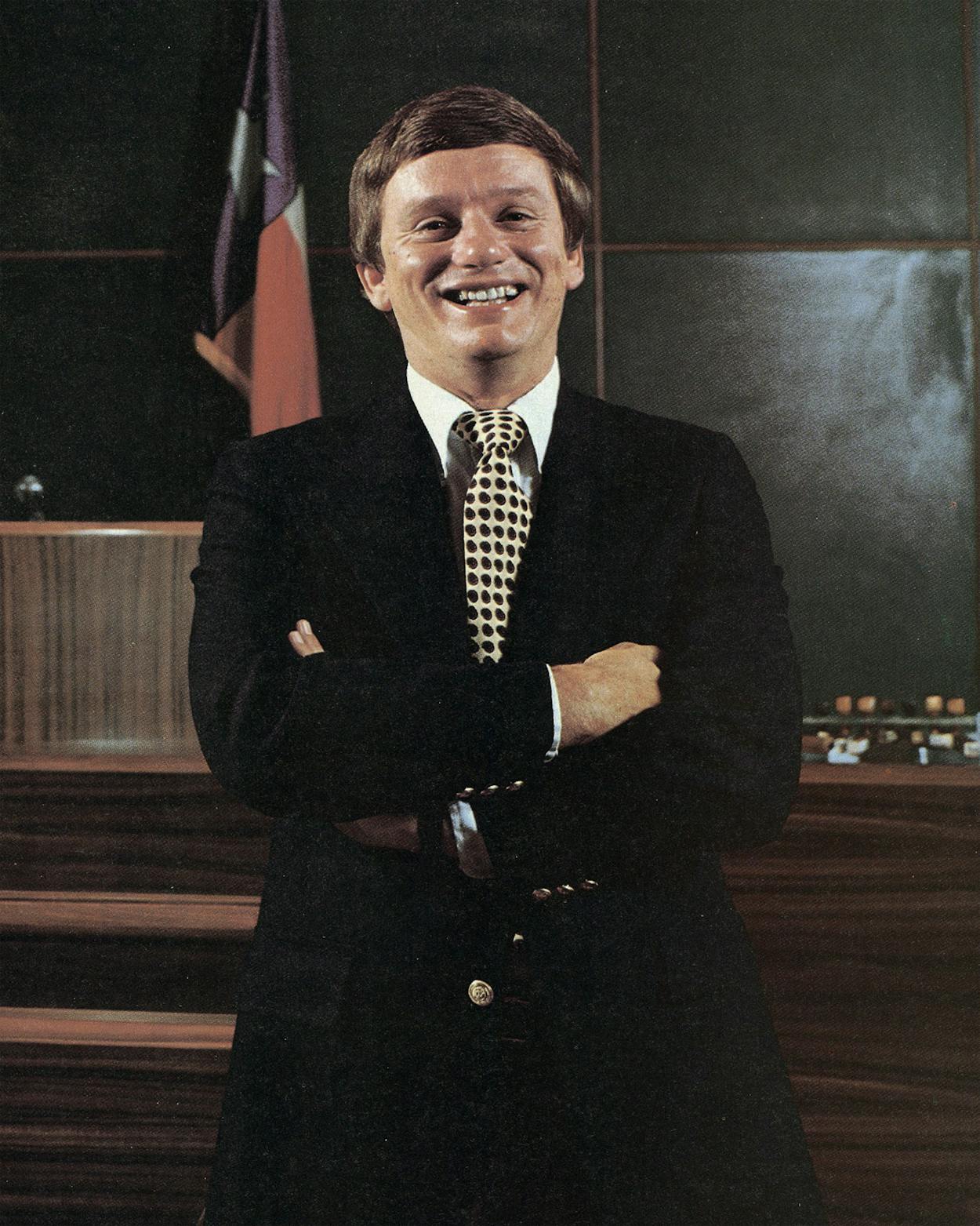

Three days later the case is resting on the desk of Russell Hardin, Jr., prosecutor for the State of Texas. Deep in his gut, beyond disgust and outrage, Hardin can feel an alarm go off as he reads the documents. In the six years that he has been a prosecutor, he has seen it all—rape, child abuse, murder, you name it. But only a few cases have ever set off the alarm, that special inner voice that says, “The person who did this deserves to die for it.”

“What do you do with something like this?” says Hardin. “It’s just about the worst case I’ve ever seen.” That doesn’t mean it’s a sure thing—anything but. There are big problems with the Bonham case. The suspect is placed at both the beginning and the end of the incident by hard physical evidence, but most of the crime happened sometime in between. It’s a circumstantial case, oddly enough. There are no witnesses; no one can actually tie Antonio Nathaniel Bonham to the abduction, the rape, or the murder. “Maybe the defense will say it was an accident,” Hardin says. “In fact, I’m sure they will. You know, this may be the first death penalty case I’ve ever done that I actually feel good about.” He does not smile.

But the prosecutor is usually smiling, and he has a terrific smile, broad and unrestrained. We’re in the bowels of the 262nd state district court, going through a morning ritual known as docket call, which rids the system of a huge menagerie of cases—everything from unauthorized use of an automobile to resisting arrest—that for one reason or another don’t merit a trial. The tiny room where Rusty Hardin is holding court is crammed with file folders and young men in three-piece suits. Their eyes are piercing and clear, their shoulders sturdy and cocky, their hair clipped and blow-dried. Rusty looks like the rest of them, except for his gogglelike wire-rimmed glasses and slight overbite. And the smile.

“Could I have it quiet?” Hardin asks, smiling. “I’m trying to do the Lord’s work here, and I’m just not getting any respect.”

Prosecutors are about the cheerfullest damned bunch of people I’ve ever been around. And the most enigmatic. Why is Rusty Hardin smiling? It could be ego. I’ve been sitting here next to him for a couple of hours, and I have yet to see a defense attorney beat him or even get the upper hand. Or it could be pressure. I know some brain surgeons who smile all the time. Or it could be pride. Hardin is very good at what he does. In six years, he’s never lost a felony case. Maybe he has a right to smile. Then again, it could be that it is fulfilling to perform the Lord’s work; maybe there is some mysterious inner peace that comes to men and women who make their living by putting criminals behind bars. “I enjoy my work. It’s fun,” says Hardin. “You tell me how many people can actually say what they do is fun. I’ve said it before—it’s a crime to pay me for doing this. Does that make any sense?” Well, I’m not sure, but it’s not the first time I’ve heard it.

When I find out why these people are smiling, I may also find out something elemental about the ungainly contraption known as the criminal justice system. Whether smiling or frowning, that innocuously titled public servant the assistant district attorney is probably the most powerful and the least understood cog in the whole system. Finding out what makes him tick might help me understand whether the system really works—or whether it just seems to.

Oh my God,” Rusty Hardin says, loudly, but to himself. “Oh, my God.” It is Monday morning, October 19, and testimony in the capital murder trial of Antonio Nathaniel Bonham is an hour away. The case has attracted only moderate attention from the press. Most reporters have chosen to cover the felony weapons possession trial of suspected hit man Charles Harrelson. Funny how the star system of crime works: Harrelson is on trial for a crime that under most circumstances would be only a misdemeanor, yet because he is a suspect in the assassination of Judge John Wood, the corridor outside his courtroom is clogged with reporters and spectators. Tony Bonham, on the other hand, is on trial for the sort of random, senseless crime that strikes fear into all our hearts, yet his trial is barely noticed. It’s too bad, because in a sense this simple death penalty case is what it’s all about. Either the system works at this or it doesn’t work at all.

The jury has already been selected by the arduous, boring process of voir dire. It’s a good jury, Hardin thinks. But he has taken a risk with some of his choices. It’s a little bit difficult to find twelve ordinary citizens who are willing, even if shown the proper evidence, to put a person to death in the name of justice. Some prosecutors go by the book, selecting men over women, Baptists and Lutherans over Catholics and Jews, whites over blacks, those with an anti-intellectual bent over better-educated types, those who have had a crime committed against them over those who haven’t. Hardin prefers a less structured, more visceral approach. “I like people on there that I can communicate with, people that I think I can get along with,” he says. “I think the ability to follow through with convicting someone to death goes beyond a religion, say, or a line of work.”

A jury is not really selected; it is arrived at by a process of elimination. A jury panel of citizens is brought to the court, and each of them is questioned in depth by both the prosecution and the defense. Each side may eliminate, for any reason, up to fifteen of the potential jurors. “It can be a real chess game,” Hardin says. “You don’t want to use up your strikes too fast. Ideally, you want to be sitting there with a handful of strikes left, while the opposition has only one left.”

In this case, the defense attorneys used all but one of their strikes; Hardin wound up with five left. In doing so, he allowed a scientist onto the jury, a young man with a master’s degree in physics. Ordinarily, intellectuals—especially scientists—are not good state’s jurors. They quibble too much with physical evidence, theorize too much, and have a tendency to be put off by courtroom histrionics. He also allowed a woman on who said during voir dire questioning that she really wasn’t sure she believed in the death penalty. Though some people who claim they aren’t in favor of the death penalty eventually are able to “push the button” when presented with the facts, a good prosecutor has to be wary of any soft spot in the jury, for in a capital case the odds are substantially less in his favor than in any other kind of case. If only one juror refuses to give the death penalty, that punishment must be eliminated from consideration; the most the defendant can get is life.

Hardin’s logic in this case is that the facts are so gruesome that even a person with ambivalent feelings about the death penalty will be convinced. He wants an intelligent jury because of the complexity of the case: there are actually two scenes of the crime and three different crimes. Because the case is largely circumstantial, he wants people with enough common sense and imagination to piece together the mass of physical evidence he will introduce. There is no admissible full confession, no document that says, “I did it.” There is no eyewitness, no one who can stand up and say, “He did it.” Under the circumstances, Hardin feels more comfortable with thinking people than with merely right-thinking people.

The result of the jury selection is a curious mixture. There are four women, one black man, three Catholics; only three of the jurors are over forty. Aside from the physicist, there are a product planner, a mining engineer, an auditor, a computer programmer. This jury will be a good test of Hardin’s skills as a prosecutor and a good test of public sentiment about the death penalty.

Appropriately, perhaps, it is the jury that is causing Rusty Hardin’s anguished outcries this morning. A juror has just called in sick; he can’t make it. “What’s wrong with him?” someone asks.

“He’s got the runs,” Hardin says, shaking his head. “Says he lost it once over the weekend and he doesn’t want to take a chance.”

The trial can proceed if the judge decides to replace the stricken man with the alternate who was selected during voir dire. But the state district judge in the case, Doug Shaver, doesn’t want to do that. This is his first capital case as a judge, and he is aware that using the alternate now could create a crisis later. If another juror were to fall ill, the trial could proceed with eleven jurors—but only if the defense attorneys agreed. Since this is a death penalty case, it’s unlikely that they would. The judge decides to put the trial off until tomorrow morning.

The assistants and witnesses and clerks in Rusty Hardin’s seventh-floor office are visibly deflated by the news. A capital murder trial is much like a Broadway opening; its participants psych themselves up to a fever pitch, geared toward the moment when the curtain goes up. Any delay destroys the momentum. It can also mean a logistical mess. Witnesses have to be lined up all over again, and evidence being brought from the crime lab has to be put on hold.

In this case Hardin has a greater concern: the victim’s husband, J. C. McGowen. Since July 9, the day he found his wife’s body under her car, McGowen has waited patiently for the system to avenge her murder. Now Hardin must tell him that there’s another delay.

McGowen, a meek, balding man in his fifties, nods quietly as Hardin explains the problem. Hardin then reviews some evidence with him. It is clear that even though he thought he was ready to go this morning, the day’s delay has afforded him valuable time to get some things in order. McGowen will be a key—the key—state’s witness. Numerous personal effects spotted with blood were found along the road where the car and the body were left; they obviously had been tossed from the car by the murderer in an attempt to get rid of evidence. Hardin needs to be certain that McGowen can identify them as belonging to his wife. It is an excruciating moment. I’m not sure I’d have the spine to show a man objects covered with his wife’s blood.

Hardin shows McGowen a large plastic sack of Styrofoam cups. “Were these the kind she used to buy?”

“Yes,” McGowen says. “She used to bring them because she made coffee for her students.” I can see Hardin making a mental note to make sure the jury hears that.

“This?” Hardin asks, holding up a blood-spattered paperback book. It’s an Aggie joke book.

“Yes. Her granddaughter used to read those to her when they drove around in the car.”

Eventually McGowen’s frustration and anger come to the surface. “I don’t know much about the law,” he says almost apologetically, “but it seems like they could prosecute him for a lot of things—the robbery, the rape, the murder. Why just the one charge?”

“We can only convict him of one thing,” Hardin explains, “and we always go for the most serious one—in this case, the murder.” The other offenses won’t be forgotten, he assures McGowen. The reason Bonham stands accused of capital murder is that he allegedly murdered someone in the course of committing another felony. McGowen seems confused, and I can’t really blame him.

The most depressing thing about any courthouse is the look of confusion and helplessness on the faces of victims and their loved ones. The righting of perhaps the biggest wrong that has ever happened to them is completely out of their hands. It’s the State of Texas v. Antonio Bonham, not J. C. McGowen v. Antonio Bonham. I can’t help thinking that one reason the public tends to be hostile toward police officers and lawyers and judges is that ordinary people feel left out of something that vitally affects their lives: the battle against crime.

After McGowen leaves, we run over to the Houston Police Department photo lab to check on some evidence. As usual, Hardin has put together a real dog-and-pony show for the jury. He will show dozens of mounted color photographs of each scene, the body, the automobile; he also has a twelve-minute videotape of the area where the automobile was abandoned. He knows that even capital murder trials can get boring and that pictures can keep a jury awake—and because there is no full confession, no eyewitness account of the crime, Hardin must recreate it. He wants the jurors to see that lonely stretch of road where Marie McGowen was murdered; he wants them to put themselves in her place—in the trunk, on the ground, in the clutches of Antonio Bonham. The pictures are his only chance of getting them to do that.

The head of the photo lab is a friendly red-faced man named Sherwood Bradshaw, who introduces himself by saying, “Please call me Tom.” Tom has spent the entire weekend shooting the scene from a car, from a helicopter, from every conceivable angle. The result is a thorough time-lapse sequence of the crime. As we leaf through the photos, Bonham’s defense attorneys, Vic Driscoll and Tom Dunn, arrive. Driscoll is fortyish, swarthy and handsome, reminiscent of Al Pacino; Dunn is fiftyish, with a crinkled, disheveled face, reminiscent of Lee J. Cobb. They have come to review the evidence themselves. Under state law, the prosecutor must show the defense some of what he intends to introduce. The defense does not have to return the favor.

We retire to a cluttered room at the back of the lab to view the videotape. It is a stunning, dramatic piece of evidence, and as the tape rolls I can see Driscoll’s lips tighten. Most of the footage was shot through the front window of Hardin’s car, as it retraced the likely route of the murderer. The dirt road is spooky and desolate, surrounded by empty fields; the sky is a malevolent purple-gray. The tape ends with a shot of a policeman, first pointing to a large rut made by the back wheel of the car when the front wheel got stuck on top of the victim, then sitting by the side of the road in the position Hardin presumes Marie McGowen was in when Bonham ran her down.

I am curious and troubled about this videotape. Still photographs are one thing; a jury has a right to see all the evidence, the best evidence available. But moving pictures have an entirely different effect: they recreate the crime in all its horror. I wonder aloud if using the videotape isn’t stretching things a bit. Could a juror really make a dispassionate judgment based on the evidence after seeing that?

“Well,” says Hardin, “I think we’re way behind civil law in this. I want those jurors to be able to put themselves in the victim’s place. I see nothing wrong with reenacting a crime.”

“Isn’t it prejudicial? I mean, that looks like a Brian De Palma movie.”

“It’s prejudicial,” says Hardin, smiling. “The question is, is it relevant? Introducing a bloody murder weapon is prejudicial too, but it’s relevant.” The argument makes sense—under the law. But I am still disturbed by the idea. What’s next? A soundtrack? Special effects? Split screen? Actors? Will the capital murder trials of the future include slickly produced tapes that star Bruce Dern or Anthony Perkins as the crazed psychopath?

That afternoon, Hardin and his “two man,” Wilford Anderson, a lean black lawyer with high cheekbones, delicate features, and the perpetual shadow of a smirk, run through the case they will present to the jury. We are in Hardin’s cramped office, surrounded by boxes of evidence, piles of mounted photographs, more stacks of those ubiquitous files, and a lot of cigarette smoke. How haphazard the preparation for a capital murder trial seems.

“What do we make exhibit number one?” Hardin asks.

“This,” says Anderson. “No, this.”

Photographs and other evidence are matched with witnesses on a master list; all the witnesses and all the evidence in the world won’t make sense to a jury unless the one goes with the other. Witnesses drop by and are rehearsed on what to say. I begin to understand that the preparation only seems haphazard and last-minute. The matter of the State of Texas v. Antonio Bonham is actually meticulously organized in some enormous file in Hardin’s mind. A well-tried capital murder case has to fall together at the last minute, in a seemingly disorganized flurry—a kind of creative orgasm. Putting it together methodically, far in advance, at intervals, would leave the prosecutor too much time to reflect, too much time to deny good instincts, too much time to forget.

Hardin has a difficult decision to make in choreographing this show. How far can he take his key witness? He sifts through the color photos. “I’ll show him this one,” he says, fingering a shot of the white Ford LTD parked beside the road, with that open field behind it. “He can say how he knelt down and looked under the car and found his wife.

“But do I show him this one?” He hands me a photo of Marie McGowen taken after the car was jacked up and she had been extricated and rolled over. It’s a macabre picture, one you wouldn’t want to show to anyone, let alone the victim’s husband. It’s not the blood or the torn garments or the matted hair on the forehead; it’s the disfigurement of the skull. Accidentally or not, Antonio Bonham obviously hit her squarely in the head with that car. The shape of her face is grotesquely distorted, as though the photo had been taken with a fish-eye lens. And her right hand is claw up and stiff, a death throe.

“What would you do?” Hardin asks. I try to assess the problem as a prosecutor would. I don’t want to shortchange the impact of McGowen’s testimony. Part of the reason the case is so horrible is that this quiet, law-abiding man looked under the car one day and found his wife of 29 years—beaten, raped, and run down by her own car. Part of me says to do it. Show him the awful picture, let him break down and cry, let the jurors watch in squeamish discomfort. If the sight of that poor man doesn’t convince them that this is not just murder but capital murder, I don’t know what will.

But then I recall a question Hardin asked me not long after we met. “Before you get through with this,” he said, “I want you to tell me one thing. I want you to tell me who we represent.” He explained that after six years of soul-searching, he has decided that he doesn’t so much represent that grand abstraction “the state” as the victim—or really, the victim’s loved ones. That made a lot of sense to me at the time, and so I try to apply it to the problem at hand. If McGowen is, figuratively at least, my client, do I really want to put him through that? Is it decent? Is it necessary? Is it fair?

I change my mind. I decide there’s no need to make a spectacle of the man’s grief. The jurors will see the picture in due course. And they’ll see the tortured face of J. C. McGowen. Seeing those two things together isn’t necessary. Good prosecuting is a little like art. What you do isn’t nearly as important as what you don’t do.

Earlier in the fall Hardin had been asked to address an informal seminar for newly hired prosecutors. He decided to talk about prosecutorial ethics. The training session was held in a small bandbox of a courtroom on the ninth floor of the District Attorney’s Office Building. The neophytes were an interesting group; there were black and female faces—a far cry from the days when such gatherings tended to resemble a Sigma Alpha Epsilon beer party.

“You have incredible power to change people’s lives,” Hardin told the recruits. “Don’t abuse it.” He urged them never to take themselves too seriously and to listen to defense attorneys. “Sometimes they have a point.” Then he admonished them, “Don’t think God anointed you an assistant district attorney to go to war.

“Don’t ever be afraid to dismiss a case if it’s justified,” he added. “That’s just as important a part of the prosecutor’s work as winning trials.” He warned them that they wouldn’t be promoted on their won-lost records. I surveyed the eager young faces in the room. The rhetoric sounded good, and I thought Hardin meant it, at least most of it. And he was right: a justifiable dismissal is as important as winning a capital murder trial; in fact, it may be more important. But these recruits clearly wanted to get ahead, and I doubted that any of them truly believed they would score as many points from a “nolly”—prosecutorese for a dismissal—as from a “notch”—a trial win.

Hardin invited the recruits to ask questions about problems they had encountered during their first few months on the job. One asked about judges who seem to encourage plea bargaining. “Don’t get co-opted to where you think you have to do what the judge says,” Hardin responded. Someone else asked how much the prosecutor is obligated to tell the defense about the case at hand. Hardin explained that he himself allows defense attorneys to see all of his files on their clients—something that, by law, he really doesn’t have to do. “But I don’t think it’s my responsibility to tell a defense attorney or a defendant that, say, he has a good motion to suppress the evidence on a bad search and seizure,” he said. “It’s not my responsibility to tell the defense that.”

His audience was beginning to grow restive, so Hardin summed things up. “You may make more money later in life, but you won’t have more fun practicing law than as a DA,” he said. “I cannot be paid enough to do something else.”

The young prosecutors left, smiling.

I am chatting with defense attorney Tom Dunn when Antonio Nathaniel Bonham is ushered into the courtroom Tuesday morning. His arrival has an effect much like the entrance of the matador—no, the bull—into the ring. “Hi, Tony,” Dunn says. Tony, a diminutive but massively muscled young man, nods. Like so many defendants accused of the most horrible crimes, he doesn’t look the part. His cheekbones are high and firm, his hair close-cropped. He looks a little like a miniature Reggie Jackson. Except for his gaze, which is not really mean, just distant—somewhere else all the time.

Judge Shaver, who looks as if he was born with the avuncular features of a judge, calls the room to order. The jury is brought in; the indictment is read; Hardin is asked to make his opening statement. It is a dull but necessary way to begin a trial. More than anything else, a criminal trial is like a Russian novel: it starts painfully slowly, and with each successive character, each successive revelation, the pace picks up, so that by the time the prosecutor reaches his final argument, the drama is racing at breakneck speed toward its climax.

Hardin’s opening statement is subdued and clinical; no need for histrionics yet. He explains that the state intends to show that on July 9, 1981, Mrs. Marie McGowen was abused and brutalized in just about every way imaginable by Antonio Bonham. He sketches out his version of the events: as Mrs. McGowen arrived at work that morning at 7:15, she was ambushed by Bonham, assaulted with a brick, and placed in the trunk of her own car. Blood and some of her personal effects found at Massey Business College will prove that. At this point the chronology becomes cloudy. Presumably Bonham drove Mrs. McGowen around for up to four hours. At some time during that period he raped her and robbed her.

The evidence will further show, Hardin continues, that three different witnesses saw Mrs. McGowen’s white Ford LTD being driven by a young black male along Schurmier Road near Hobby Airport about eleven-thirty that morning. The car was next spotted by patrolling police officers around five o’clock that afternoon; its rear right wheel was stuck just off the muddy shoulder of the road. By that time, officers who had been called to the scene at Massey Business College had put out a “flag” on the car. Officers at the Schurmier Road scene called J. C. McGowen to obtain keys to the trunk. After he arrived, they opened the trunk and found massive smears of blood, but no body. When McGowen squatted down to investigate the chassis, he found a body. He examined it twice before he realized it was his wife.

Hardin tells the court that from the autopsy report, it is clear that at some point that morning either Mrs. McGowen escaped and attempted to flee or Bonham removed her from the car, placed her on the side of the road, and ran her down. Evidence will show, he says, that the car was run over her forward, then backward, then forward again before becoming stuck on top of her body.

The evidence will further show, Hardin continues, that on July 17 homicide investigators arrested Antonio Bonham in connection with the murder. They had two pieces of hard physical evidence: six different fingerprints lifted from the Ford LTD matched Bonham’s prints on file, and a set of keys found at the Massey Business College scene fit doors in the homes of Bonham’s mother, father, and sister. Finally, Hardin adds, during the morning of his arrest Antonio Bonham confessed to much of the crime to Detective Gil Schultz. He admitted assaulting and abducting Mrs. McGowen and wanting to steal her car. While not admitting that he raped her, he did say he “abused” her, but he said he was only trying to “scare” her with the car when he “accidentally” ran over her.

As Hardin wraps up his opening statement, something very strange happens. I have been studying Tony Bonham while Hardin speaks, trying to see some sign of emotion on his face. It has remained blank, as if he is in a trance. But as Hardin reviews the evidence one last time, Bonham nods ever so slightly, as if to say, “Yeah. That’s about right. You got it.”

The trial drags miserably through the morning. The police officers who investigated the scene at Massey Business College are brought to the stand; the colleagues of Mrs. McGowen who discovered the blood are brought on; numerous pictures are introduced. The jurors already look confused and bored. As we leave for the noon recess, Hardin says, “This is really dull. We have got to get this thing alive. They’re going to sleep. Maybe I ought to moon ’em between questions to get their attention.”

At lunch Hardin and Anderson discuss more acceptable ways to put some punch into their presentation. Hardin intends to run through the day’s remaining police witnesses and then the civilian witnesses who spotted the car on Schurmier Road. “Then we wind up with Mr. McGowen. That’ll get their attention. Give ’em something to think about overnight. You want to keep them thinking, keep them wondering what’s coming next. I could’ve just put Mr. McGowen on the stand first and started with a bang. But it wouldn’t have made sense dramatically.”

Hardin begins the afternoon’s testimony by introducing and playing the videotape of Schurmier Road. It’s an interesting move. For one thing, he needs to introduce it for technical reasons; for another, letting the jurors see the tape now will get them to thinking. “They see it now, and it doesn’t mean much,” Hardin told me before the afternoon session began. “But wait till I show it to them again in final argument. It’ll mean something then.”

Whatever else can be said about the criminal justice system, it does not run on time. Hardin’s police witnesses go smoothly enough, but the civilian witnesses take longer than expected. And what further attenuates the proceedings is an outbreak of bickering between the attorneys. One of Hardin’s civilian witnesses, Fred Betts, had said he was willing to testify that he was “ninety per cent” sure he could identify Tony Bonham as the black male driving the white Ford he saw that morning. Although it wasn’t anything devastating—not like a positive eyewitness account—Hardin had decided to slip it in anyway. But when he asks Betts, “Do you think you can identify the man you saw in the car that day?” Betts says yes, he’s sure it was Tony Bonham.

“Could the jury retire, please?” Dunn asks. There ensues a legal argument that only a lawyer could love. Is Betts 90 per cent sure or 100 per cent sure? Dunn asks. It makes a difference.

“I’m just as surprised as Mr. Dunn at his certainty, Your Honor,” Hardin says. There is more wrangling about percentages and how they relate to certainty. One thing that is rankling about watching a criminal proceeding is how often the law and procedure in a courtroom seem to ignore human nature and common sense. Common sense tells us that one is either certain or uncertain, period. Thank God that young man’s certainty won’t be judged by a bunch of lawyers. The jury is returned to the courtroom. Hardin asks Betts, “Would it be a fair statement to say he looks like the man you saw that day?”

Betts, who seems more confused than anyone, says, “I’m not one hundred per cent sure. There’s just a shadow of a chance . . .”

As we walk out at day’s end, Hardin shakes his head and smiles. “Well, we can start with McGowen in the morning. I know they’re waiting for something to happen. Little do they know, so are we.”

Over drinks at a place in downtown Houston called the Wooden Nickel, Hardin is still musing about how to make something happen. “We need to come up with a catch phrase for Tony. Something that’ll stick in the jurors’ minds. I had this one death penalty case where the kid was known to smile all the time. So I started referring to him as Smilin’ Johnny. Maybe we can call Tony ‘Coping Tony.’ He says in his confession that one reason he got in trouble was ‘the pressures of coping with society’ after getting out of prison. Coping Tony. I like that.

“I think it is the victim we represent. For example, I’ll never recommend probation in the case of theft of a person. If that guy took the trouble to rob a person, then I don’t want to probate him. It’s like restitution: for a long time defense attorneys said the system should not become a collection agency. Well, why shouldn’t a victim at least have the right to get what he lost out of the crime? I’m not so sure a criminal shouldn’t have to pay back the insurance company, no matter what he pays the victim. Why should a criminal benefit from the free enterprise system?”

I ask him how that applies in a death penalty case. “I don’t have illusions about the death penalty,” Hardin replies. “My thing is not whether it will deter any other crook out there, it’s whether it will deter Bonham.” and J. C. McGowen? “Well, there’s no way the system can do enough to make amends to him in a case like this. I guess we can say we punished this man with the worst possible punishment society has to offer.”

When Rusty Hardin looks back over his past, it is clear to him that the Lord’s work was was anything but a lifelong long calling. “I always envisioned myself as a defense attorney. I remember when I was in law school at SMU, I heard Racehorse Haynes speak. He talked about what a great feeling of accomplishment it was for a defense attorney to walk into federal court, face all the power and majesty of the U.S. government, and beat them single-handedly. That impressed me.”

Indeed, for several years Hardin wasn’t even sure he wanted to be a lawyer. After graduating from Wesleyan University in Connecticut in 1965, he considered the idea of law school but took a job teaching American history at a small private school in Montgomery, Alabama. He taught for a year and then joined the army because he “felt guilty.” There he distinguished himself by being the only half-blind recruit to slip through OCS training. “I just memorized the chart on the side of my bad eye. When they found out, they called me Cyclops.” During a fifteen-month stint in Viet Nam, he further distinguished himself by sleeping through an enemy mortar attack.

After five years in the Army, Hardin worked in Washington for a congressman from his home state of North Carolina. He’d always thought he might like to go into politics, but after a year law school beckoned. He sent out applications to thirteen schools; all but SMU rejected him. He made only average grades, but that didn’t matter too much. “I was thirty-three. I just wanted to pass the bar and practice some law.” Though (like most law school students at the time) he considered prosecuting to be anything but the Lord’s work, he did show an immediate aptitude for criminal law. “I didn’t do so hot in the other stuff. My tax law professor agreed to pass me my last semester if I would do two things: never practice tax law and never tell anyone that he’d been my tax law professor.”

Hardin took a job with the Harris County DA’s office in 1975 because it seemed like the best place to practice trial law. He had to start out in the “nonsupport” section—the division responsible for locating husbands who fudge on their child support payments. By literally begging for trial work and showing a desire to try “anything, just anything,” he eventually landed a spot as the third prosecutor—the “three man”—in a county court. His first felony case was a tart taste of big league prosecution. “I probably should have known something was up when I looked at the file and saw that about thirteen other prosecutors had signed off on it. The damned thing had been around for about two years. Unfortunately, I had about an hour to prepare for it.”

The case involved the assault of a young homosexual by his lover in a Montrose gay bar. The defendant, an operating room technician, had attacked his lover with a scalpel. “It taught me a thing or two about jury selection right off. I not only had to get people who would look at this as more than a domestic spat but I had to get people who wouldn’t be offended by these two gays.” He got a conviction, the first in a string of some sixty felony convictions. “All I ever lost were two no-test DWIs.”

After three years, he reached what prosecutors consider the pinnacle of their profession: his current slot as a chief felony prosecutor in a district court. As a chief, Hardin can pick and choose his cases, concentrating on the most challenging ones—the death penalty cases. Thus far, he has tried five, failing only once to persuade the jury to decide for the death penalty.

“When I tried my first death penalty case, I thought I might feel guilty. I expected it. You don’t ever feel good about it. But I do think there are some people who by the nature of what they do deserve nothing less. They are unsalvageable. I always try to think about the victim. Is it fair to the victim for anything less to happen to the guy who did this awful thing?

“I don’t look back on any of those cases. That’s one reason I’ve never left this job. I might have to sometime for money reasons. But the main thing is that in six years I’ve never once been asked to do anything I didn’t believe in.”

I catch Mr. McGowen in the hallway before the trial resumes on Wednesday morning. He is clearly nervous about testifying, and for a moment I wonder if it is worth it to make him go through this—purely for the dramatic effect. Criminal trials are not the dispassionate, clinical proceedings we’d like to think they are; in a fundamental way they are contrived dramas, designed to sway the jurors as much through appeal to their emotions as through presentation of hard facts.

I ask McGowen a question that has been bothering me ever since I began covering crime. Will all the expense and time and trouble the state is going to here really make amends, even the score, supply him with some inner peace? “No,” he says evenly. “If it can stop this guy from doing it to someone else, i’m for that. But for me . . . for me, it won’t.”

Hardin’s task with a witness like this is not to overplay it; McGowen’s pain and grief will come through just fine without much help. When he takes the stand McGowen tells the jury that he is 54, a plant supervisor for Charter Oil. He had been married to Marie for 29 years. She had one child from a previous marriage and they had a ten-year-old granddaughter. “What kind of woman was your wife?” Hardin asks.

“She was kind . . . and hardworking,” McGowen says, his voice thickening.

“After you left her that morning, did you ever see her alive again?”

“No.”

Hardin has McGowen narrate how he received a call from the police that morning, asking him to come to Massey Business College, and how he found his wife’s “lunch and her glasses lying on the sidewalk.”

“Could you describe your feelings . . . at Massey?”

“Yes, sir. I thought that the worst that could had happened.” His voice quakes.

Hardin pauses for effect, then asks him if his wife suffered from any unusual psychological disorder.

“She had claustrophobia,” he says. “She was scared of getting caught or getting held or anything. I believe if anybody would have held her, she would have suffocated to death.”

Hardin pauses again. He hopes to allow the jury time to translate that information about Marie McGowen’s claustrophobia into a realization of the woman’s terror as she lay bleeding in the trunk of the car.

As Hardin leads McGowen through the horror of that day, I begin to see the integrity of his style as a prosecutor. Most prosecutors go for fire and brimstone; every move, every word is calculated to whip the jury into a revival-meeting frenzy. They emanate a kind of self-righteous anger toward the defendant, an anger they hope to transfer to the jurors. And they portray themselves as glad to be there doing the Lord’s work, glad to be putting this awful man to death. They urge the jury to join them in the crusade.

Hardin’s method is more subtle. As he paces about the courtroom, he emanates not anger but disgust. He’s not glad to be here; he’s not happy about asking McGowen these awful questions; he’s not at ease having to show these grisly pictures. His attitude seems to communicate directly with the jurors, who also appear anything but happy to be here.

Hardin leads McGowen slowly to that afternoon, when he was again called by the police and asked to go to Schurmier Road. “I wanted to see if it really was her briefcase [back by the rear tire of the car],” McGowen says, “and so I got over in the ditch and squatted down and saw her body. . . . The car was on top of her and she was sort of squashed into the ground. I had to brush her hair back off her face to see if it was her.”

“Why did you have to brush her hair back?”

McGowen explains that it was matted with blood.

“How did you know she wasn’t alive?”

“She was stiff and cold.”

Now Hardin is ready for the pièce de résistance. He had already introduced and shown to the jury a picture of Marie McGowen and her granddaughter, which he had McGowen identify as “the way she used to look.” Now he was ready to show the jury the way she looked July 9, when the police officers extricated her from beneath the automobile.

He asks McGowen what sort of funeral service they had for his wife. “We had a closed-casket service because the undertaker advised that we not have an opencasket service.” Hardin pauses to let the jury wonder. Then he has that awful, gruesome picture of Mrs. McGowen introduced into evidence. It’s fascinating to watch the jurors look at it. Some stare at it long and hard; others glance at it and quickly pass it along. But all of them seem to be trying hard not to look shocked.

“Let’s recess for lunch,” says Judge Shaver. Hardin beams after the jurors leave the courtroom. His timing was perfect. “That’ll give ’em a little something to think about over lunch,” he says. “Unfortunately, we’re going to have to bore ’em again this afternoon.”

Hardin wasn’t kidding. In the afternoon the jury is lulled by an endless stream of police and fingerprint experts. Hardin is laying the groundwork for the next chapter—the arrest of Antonio Bonham. It’s deadly stuff, but it must be in the record. No doubt most of the jurors would take Hardin at his word that the prints found on the car were Bonham’s and that the keys found at Massey did fit the doors in Bonham’s family’s homes. And their common sense would tell them that that evidence alone is pretty incriminating. But each step, each link in the chain of evidence, must be traced and retraced, not really for the jury’s edification but to perfect the record. At some point in any trial, the prosecutor is trying his case as much against a court of appeals as he is against the defense. That is especially true in this case, where Dunn and Driscoll have barely had anything to say. The trial is nearly two days old, and they have asked very few questions on cross-examination. They have obviously chosen to take the low road—to keep their mouths shut, to avoid irritating the jury with nit-picking and bickering, and to hope that Hardin commits some kind of “reversible error” for the purposes of appeal. Only two days into this capital case, both sides are basing their strategies not on what the jury is thinking but on what a distant appeals court will think.

Late in the afternoon we are treated to a stunning example of the strained relationship between trial law and common sense. The witness is homicide detective G. C. Schultz, the man who took Antonio Bonham’s confession in the wee hours of the morning of July 17. Schultz is the archetypal homicide detective—paunchy and rumpled, with haggard eyes and a brave smile. He testifies that several officers arrested Bonham at his father’s house about 3 a.m. on July 17. Bonham was taken to police headquarters, where his rights were read and reread to him; he continued to say he didn’t want an attorney. The detectives got him cigarettes, coffee, and some chewing tobacco. About 7 a.m. he signed a partial confession, which admitted to the abduction and the aforementioned “abuse” but claimed that the death of Mrs. McGowen was an accident.

So much for what the jurors hear. What they don’t know, what they won’t know until the trial is over, is that Tony Bonham made another confession, a more incriminating one. Before drawing up his formal written confession, the defendant admitted orally to Schultz that for three or four mornings he had stood at a bus stop across Main Street and watched Mrs. McGowen arriving at Massey Business College; he also admitted robbing and raping her. While never specifically admitting to murder, he did tell Schultz that the way he knew the woman was dead was that “she stopped making noises” under the car. And when Schultz said, “You’ve taken this man’s wife. Can’t you at least give him back his wife’s wedding rings?” Bonham said, “F— the old man. I don’t owe him anything.”

That confession—the single most damning piece of evidence the state could present—can’t reach the jury’s ears because of something called the Texas Oral Confession Statute. Unlike any other state in the nation, Texas still clings to the notion that any oral statement made by a defendant is simply inadmissible for trial unless it leads the police directly to some “fruit of the crime.” In other words, if this murder had been a shooting, and upon arrest Tony Bonham had said something like “You got me. I did it. The gun’s in the front closet,” and the gun was in the front closet, then the statement would be admissible. Otherwise, the jury is stuck with the defendant’s “formal statement”—a document that he is allowed to edit and alter in any way he pleases.

Bonham’s attorneys, Dunn and Driscoll, now introduce a motion to have the written confession of Tony Bonham banned from the proceedings. Though it appears that the confession was taken with the utmost care, placing a challenge to it in the record can form the basis for an appeal. Their argument is that there is enough suggestion of coercion to render the confession tainted.

The situation has one beneficial side effect for Hardin: to bolster their claim that the written confession might have been coerced, the defense attorneys have decided to allow Antonio Bonham to take the stand—outside the presence of the jury, of course. Hardin’s eyes light up at this opportunity to grill the defendant. Cross-examining the defendant is the apex of the Lord’s work, and although the whole exercise is being conducted entirely for the benefit of the appeals courts, Hardin is nevertheless anticipating the moment.

On direct examination by his attorneys, Bonham claims in a thick ghetto drawl that when the police came to arrest him that morning, they had their guns pulled and said things like “Tony, we got you, man” and “By not cooperating, you’re only hurting yourself.”

“I was under a lot of mental pressure with all of them talking to me at once,” Bonham says. “It was just too much, you know.”

Hardin begins his cross-examination by approaching Bonham and smiling. Unlike most prosecutors, he does not favor the rock ’em, sock ’em approach to interrogating a defendant; he prefers to cajole. “With these real tough types, playing TV lawyer only makes ’em mad. They freeze up on you. I like to kind of make friends with ’em and get ’em to say things before they realize it.” It’s a style that has served Hardin well. In the capital trial of Kenneth Dunn, a young man convicted of murdering a bank teller during a robbery, he persuaded the defendant to step down in front of the jury and actually demonstrate how he shot the woman. He once even had what lawyers call a “close encounter of the Perry Mason kind”—sweet-talking a defendant into confessing on the stand.

“You’ve faced this issue before in your life, haven’t you?” Hardin asks. Bonham admits he has. “In all fairness, you’ve been dealing with the authorities for the past nine years, haven’t you?” Then, in an appeal to Bonham’s obvious tough-guy image of himself: “Are you telling me that you’re the kind of man who would let the police make you do something you didn’t want to do?”

“I’m not going to admit to that,” Bonham says sheepishly, realizing too late the trap he’s been drawn into. Hardin seizes the opening: “Nobody hit you, did they?”

“No.”

“You didn’t say anything to your sister [when you called her] about being scared, did you?”

“No.”

“You deliberately leave a lot of things out of this, don’t you?”

“What you mean?”

It’s all downhill from here. By the time Hardin is through with Bonham, he has gotten the defendant to admit in so many words that the confession wasn’t coerced at all, that he knew exactly what he was doing—that, in fact, if someone tried to force him to do something, he’d take care of one or two of “their anatomical parts.” Hardin thanks him, smiling, and Bonham smiles back.

Thursday morning the trial is delayed for an hour because a fellow inmate swiped Tony Bonham’s shoes the night before. I chat with a diminutive woman who identifies herself as Mrs. Wilson, one of the better-known “trial groupies.” She says that she tries to see all of Mr. Hardin’s big cases because his are the most fun to watch. Asked how she thinks the case is going to come out, she says, “Oh, no. I never make predictions.”

The judge has overruled the defense’s motion to suppress the written confession, and so parts of it are read to the jury. This is Hardin’s ultimate teaser. He has tied Bonham to the crime in every way imaginable; now he wants to shift the jurors’ attention to the victim. Their worst fears about what Mrs. McGowen actually went through will be confirmed soon enough by his last witnesses—the medical examiner and an automobile homicide expert.

The medical examiner in the case is Dr. Eduardo Bellas, a distinguished-looking physician. His testimony is by far the most gruesome of the trial; several of the members of the McGowen family leave the courtroom as Bellas details just what Tony Bonham and that car did to Marie McGowen. The blow with the brick alone was sufficient to crack her skull. She had been raped so savagely that her vaginal tissue had been torn. The automobile had hit her squarely on the right side of her forehead, causing another massive skull fracture. The weight and movement of the car had subsequently crushed her ankles, her chest, and her pelvis and had snapped her neck. While the car was resting on top of her, its catalytic converter had seared and blackened a swath of flesh across her back. I watch the jury—silent, motionless, and riveted on the doctor’s testimony. By easing the jurors through the crime, Hardin not only has managed to keep their attention but has transformed Bellas’s dry, clinical testimony into the climax of the trial.

With his final witness Hardin is taking a gamble. For days he has been searching for an ending to his show, something that will tie all those circumstances together. Since what really happened out on the road is a matter of conjecture, he wants to be sure the jurors are left with his conjecture, so they won’t do too much theorizing on their own during deliberation. He decides to bring in Sergeant Steve Fowler, an automobile accident investigator. Hardin is worried about this testimony: sometimes experts can backfire on a prosecutor by engendering more doubt and confusion in the jurors’ minds than they clear up.

Fortunately, Fowler is a dazzler of a witness—handsome and articulate and credible. His reconstruction of the homicide virtually eliminates the possibility of an accident. He states that given the injuries suffered by Mrs. McGowen, he knows exactly what position she was in when the car hit her and exactly what happened to her under the car. “Show us,” Hardin says.

Fowler steps down from the stand and sits on the floor. He explains that because Mrs. McGowen’s skull was battered and cracked on the right side, it stands to reason that the auto’s bumper hit her first, while she was slumped in a semi-prone position. The car then tumbled her over on her left side and came to rest on her body.

“What would stop the car?” Hardin asks.

“Oh, she would. A hundred-and-forty-pound object would stop a car, if you were up on it.” The car then must have gone into reverse and dragged her back over on her right side. Then it must have gone forward again; hence the huge rip in her jacket and the position of the body.

As he speaks, Fowler physically demonstrates the movement of the body. The jurors are enthralled. As he twists and turns and contorts his body on the ground, they stand to watch. Though it is speculative, his testimony is powerful. The victim wasn’t merely bumped or brushed. She was run over. And she was run over not one, not two, but three times. Hardin pauses, allowing the jury to stare at Fowler on the courtroom floor. “Pass the witness,” he says.

The next day’s proceedings are delayed all morning because of an obscure but crucial process known as drawing up the charge to the jury. It is remarkable that an expensive, extensive endeavor like a capital murder trial comes down to such a seemingly inane process. In lay terms, the drawing-up of the charge means that the prosecution and the defense write in formal language just what law they want the jury to consider in rendering a verdict. From Hardin’s point of view, the matter is simple: the state will ask for death—nothing less. From Dunn and Driscoll’s point of view, however, the matter is much more complex. After sitting on their hands all week, they now enter the most important stage of the trial as far as the defense is concerned: how all of those awful facts about what Tony Bonham did fit the law. They will argue to the jury that the single act that the state alleges makes this a capital offense—the intentional murder of Marie McGowen with the car—was an accident. If the jurors have a reasonable doubt that it was intentional, they must find Bonham guilty of any of a series of related lesser offenses: felony murder, voluntary manslaughter, involuntary manslaughter, criminally negligent homicide. The law regarding all of those offenses must be included in the charge too.

Every word, every comma in the charge as drawn up by the attorneys must be precise and correct; one screw-up and the court of criminal appeals can kick the case back in less time than it took Marie McGowen to die. “It’s probably the most ignored part of any lawsuit,” Hardin tells me outside the courtroom. “It’s a pain in the ass is what it is, but it’s the thing that can screw you up on appeal.”

Hardin is obviously distracted today. This afternoon he will give his closing argument, and as is his style, he has not prepared it. “I tried preparing them for a while,” he says, “but when I gave them, they always came out stale. I’ll usually wait for something to spark me.”

The charge is finally drawn up, and Judge Shaver reads it to the jury. It is in undiluted legalese, straight out of the penal code. One woman in the jury suppresses a yawn while the judge reads.

Hardin’s “two man,” Wilford Anderson, offers the first summation. After days of taking notes, keeping track of evidence, and generally serving as Hardin’s eyes and ears, Anderson must now act as his superior’s straight man in final argument. Because Hardin will speak last, after the defense attorneys, Anderson’s job is to be brief and to the point; above all else, he does not want to tread on areas of argument that will be covered by Hardin. “Leave me Coping Tony,” Hardin told him the night before. “I want to surprise them with that.”

Anderson reviews the evidence briefly, then the law. “We can’t hear from Mrs. McGowen as to what occurred,” he says. He is a powerful speaker, much in the tradition of a black preacher, but he’s holding back, giving the jurors only enough to make them think and wonder. He closes by saying, “He got her car, but that’s not all. One reason was to rape her, and I submit to you the other one was to take her life.”

I am curious about what Dunn and Driscoll have in mind. They have presented no witnesses of their own; they have barely cross-examined the state’s witnesses. The jurors are waiting to hear something, anything that will suggest to them that this was not the worst of all possible crimes—a capital murder punishable by death.

Dunn wisely does not try to play games with the jury. The state has proved every offense beyond a reasonable doubt, he begins—except murder. Did Tony Bonham intend to run Mrs. McGowen down with the car, or was it an accident? Was he really just trying to scare her? “No one in the courtroom knows for a fact.” That alone, Dunn emphasizes, amounts to reasonable doubt.

“Can you really say what was in the mind of the man who drove the car? I am convinced in my own mind that the state has not fulfilled its burden of proof of the mind of the man who drove that car.” Then Dunn appeals to the jurors’ sense of mercy. Referring to the death penalty, he says, “I didn’t write the law. If we let vengeance and anger replace the law . . . then we’re throwing in the towel in the long run.”

Dunn’s summation lasts only fifteen minutes, and the jurors look confused. We usually envision criminal trials as they are portrayed on television—hotly contested affairs where the defendant’s innocence is in question up until the last minute. But most trials are actually like this one—rather anticlimactic. It is clear from the outset that the state will win. The only question is by how much it will win.

Driscoll takes a different tack. The evidence in the case is so awful, so damning, that he barely refers to it; instead, he argues the law. He explains the law of circumstantial evidence. “If there is any other reasonable hypothesis for what happened, it must be not guilty,” he says. “Saying it is so doesn’t make it so.” It is a reasonable hypothesis, he argues, that the homicide was accidental; no firm evidence exists to make that scenario unreasonable. As long as that possibility exists, it represents reasonable doubt; as long as reasonable doubt exists, the jury must find the defendant guilty of a lesser offense.

Driscoll has pinpointed for the jurors the single rational basis on which they could find Tony Bonham not guilty of capital murder. But the argument is falling on deaf ears. Laymen are suspicious of purely legal argumentation; it always comes off as begging the question, beside the point, an attempt to divert them from the real issue. Driscoll’s dissection of the law relevant to the case is concise and logical; his problem is that he can’t bring it to life, can’t really make it mean anything in terms of the evidence in the case.

We recess for lunch, and on the way to the elevator Hardin says, “Whew! I don’t just need to do something to wake them up, I need to do something to wake myself up.” He is bothered that his summation will come after lunch, when the jurors will be sated and sleepy. Because of the complexity of the case, he’ll have to be at his histrionic best to keep their attention. Over lunch, he still refuses to organize his summation. “It’ll come,” he says, “it’ll come.” But he does mull over what his general objectives will be. In many cases, the prosecutor’s summation is an afterthought; if he’s done his job well, the jurors have already made up their minds by the time he stands to speak. But in this case, a lot of loose ends need to be tied up to convince the jury that the murder of Marie McGowen was deliberate and premeditated. “Let’s go,” says Hardin, having barely touched his lunch. “It’s time to romp and stomp.”

Mr. Driscoll has talked to you about what the law is,” Hardin begins his summation, “and maybe now you know why you didn’t go to law school.” He pauses. “I want to talk to you about Mrs. McGowen and about Coping Tony Bonham.”

He paces across the room and addresses the jury directly. He shakes his head. “If I hear one more time,” he says, his voice rising, “that what happened to that woman is somehow tied to coping with society, I think I may get sick!” The jurors had looked sleepy, but no more. With a single sentence Hardin has roused them and created an aura of disgust. He tells the jury that the senselessness and savagery of Tony Bonham’s spree should not confuse them: “He is not charged with being a brilliant murderer; he is charged with being a murderer.

“I’m going to take you on an odyssey, on the last little bit of Mrs. McGowen’s life.” With that, Hardin begins to narrate Marie McGowen’s day on July 9. He starts at home, where she had coffee with her husband. He talks about how frightening the randomness of violence is, how any of us could be victims. “Don’t ever again leave undone the things you could do with your loved ones today. Because there are other Tony Bonhams out there in the world. . . .” Hardin moves on to Massey Business College: “If you can believe this man’s statement in this confession that he went out that morning ‘sight-seeing’ . . . folks, you’re looking at the Easter Bunny. I’m him.

“I’ll tell you what sights are there on Main Street. People trying to start their normal day, and that’s what Tony Bonham wanted to prey on.

“She walks by and whammo! A sixty-two-year-old woman.”

He talks about the trunk and the claustrophobia. “Where is Mrs. McGowen? . . . Tony Bonham is driving her around in a hundred-degree-plus trunk. . . . Ladies and gentlemen, she is in either the trunk or the back seat and all this time, this man is just wandering around. . . .”

Hardin pauses and flips on the videotape of Schurmier Road. “And he drives . . . and he drives . . . and he drives,” he says, his voice rising, his right hand gesturing at Bonham. “He doesn’t do a swinging thing but keep driving . . . and driving!”

Hardin has a reputation at the courthouse for his clever theatrics in final argument. In the capital murder trial of James Means, a man accused of indiscriminately pumping fourteen rounds of shotgun shells into a Purolator truck before robbing it, he actually picked up the shotgun and dashed about the courtroom, punctuating his argument with “and then he went baroom!!” In rape trials, he’s been known to flip off the lights in the courtroom at an opportune moment and ask the jury to consider the victim’s terror in the darkness. But for my money, the videotape of Schurmier Road is the most devastating bit of prosecutor’s histrionics I have ever seen. My worst fears about the effect of moving pictures on a jury are confirmed. For all intents and purposes, the crime is being reenacted. And Hardin is no fool. He realizes the magic of the moment and simply lets the tape run. The lights have been dimmed, and there is an eerie quality to the courtroom. “Is this the action and conduct of a man who did not intend to kill her?” Hardin asks.

He talks about how Mrs. McGowen wound up under the car. “He either drags her . . . or he gets her out and says, ‘Walk’ . . . Mrs. McGowen ends up down here sitting . . . she is just drained. . . . She is alive and she could have been saved. . . . He lines her up just like at a shooting gallery. . . .

“He is planning to hit her and just drive off. . . . What do you mean, he couldn’t see her? He put her there! Either Superman came by, picked up that car, and plopped it down, or he turned it right into her, right there.”

Now Hardin gets on the floor and physically acts out what was happening to the victim under that car. “She’s like this,” he says, sitting on the floor in a kind of upright fetal position. “He guns that accelerator over her . . . and then he guns that accelerator in reverse and he pulls that body back over . . .” Hardin flops himself forward and then, contorting his body like a gymnast, stretches himself back the other way. He explains that this is when “Tony Bonham’s thirty-six-hundred-pound weapon” crushes virtually every major bone in Marie McGowen’s body. He explains how Bonham, frustrated that the car is stuck, attempts to place Mrs. McGowen’s briefcase under the right rear wheel for traction. “Is he running for help? Coping Tony Bonham gets back in the front seat again, and guns it forward again.

“He didn’t intentionally run over her?” Hardin asks. “I’m not going to show you all the gory pictures. I don’t think you need to see any more.” It’s a brilliant stroke; once again Hardin has taken the jurors only so far—and left the rest to their imaginations.

“This is capital murder if ever there is going to be one. There is nothing lesser in this case. . . . If you do not find him guilty of capital murder, then I, in all due respect, do not care what you do after that.” as Hardin strides to his chair, I finally realize the full weight of the prosecutor’s power: this trial has stretched over five days, has included twenty-odd witnesses and nearly two hundred exhibits of evidence. But none of that will have as much to do with the jury’s verdict as the final sentence uttered by Rusty Hardin. Those photographs and bits of clothing and fingerprints are by now deep-sixed in the jurors’ minds; all that matters is that the prosecutor, the man who clearly still knows more about this case than they do, has just offered them a challenge: decide what you will—but I’m telling you what the right decision is.

In the offices behind the courtroom, we sip coffee and await the verdict. I bet Hardin a lunch that the jury will be back in less than an hour with a guilty verdict. “I don’t know,” he says. “I’ll bet more than an hour. They always take that long in a capital case.” Forty minutes later, the bailiff emerges from a hallway, beaming and carrying a yellow legal pad. He hands it to Judge Shaver. “Your Honor,” Shaver reads from the pad, “we have reached a verdict.” Hardin blushes.

“We find the defendant guilty of capital murder,” Shaver intones. Hardin is expressionless, but—I’m sure I see it—Tony Bonham smiles ever so slightly. The spectators file out and shake Rusty Hardin’s hand. A matronly woman in her fifties approaches him and forces a smile. “Thank you, Mr. Hardin. Marie was a friend.”

“You’re welcome, ma’am,” Hardin says.

The quintessence of the Lord’s work, I realize, is that the prosecutor weekly, even daily, gets to see himself as a hero. Whether he really is a hero is, as a prosecutor himself might put it, a moot point; he perceives himself that way, and that’s enough to make anyone smile.

As usual, the second phase of the trial—the punishment stage—is a letdown. Any jury willing to convict Tony Bonham of capital murder in forty minutes will have no problem selecting death over the only other available punishment—a life sentence. In other kinds of proceedings, the punishment phase of Texas’ bifurcated trial system provides the most dramatic moments. After all, the biggest decision about most criminals tried is not their guilt or innocence but whether to give them 5 years or 10 years or 99 years.

Hardin goes through the motions of satisfying the requirements of the Texas death penalty statute, which says the jury must find not only that the defendant deliberately committed murder in the course of another felony but that he represents a future threat to the community. Hardin establishes this by parading out Bonham’s previous criminal record. He began his career at the age of fourteen, Hardin shows; in 1977 he received ten years in the penitentiary for two aggravated robberies and an auto theft. He had been out of prison only 32 days when he robbed and raped and murdered Marie McGowen. Driscoll and Dunn offer none of the predictable character witnesses one normally sees in the punishment phase of a trial. Indeed, a police officer sent to get Bonham’s own mother testifies that he came back empty-handed because “she said she wanted no part of this.”

Hardin is looking for a grabber, a spark for this phase of the trial; though he knows that the jurors have probably already made up their minds to push the button, he can’t let the trial tail off. He decides on an interesting gamble. He calls Bonham’s parole officer, Herman Blake, to help “perfect the record” concerning Bonham’s general reputation. Hardin knows that Bonham attended three sessions with his parole officer before he was arrested for the murder of Marie McGowen, the last one on July 10—the day after he brutalized the woman. The question is whether he should bring this out himself. It’s an interesting prosecutorial problem: when is enough enough? If the jurors have already made up their minds to go with the death penalty, they might only be insulted by one more rabbit punch while the defendant is down and defenseless. Hardin decides to let it ride, hoping that the defense will “open it up” on cross-examination.

Sure enough, Dunn does just that. He has no choice, really. His only job now is to try to save Tony Bonham’s life. One way to do so is to show the jury that after his release from prison, Bonham was a responsive, upstanding parolee. Dunn asks Blake if Bonham showed up regularly for his parole sessions and seemed to be adapting well to life on the outside. “Yes, sir.” To make the record clear, he asks Blake the dates of the parole sessions Bonham attended. “. . . and July tenth,” Blake says. Hardin looks at the jury; now he has the basis for his final argument.

It is nevertheless an uninspired argument. After Dunn and Driscoll have said things like “It might be that we should kill our problems” and “To [kill Tony Bonham] would be to compound one tragedy with another,” Hardin rises and says quietly, almost deferentially, “Have you already made up your mind? Perhaps . . . but I’m not going to take a chance.

“I never thought I would say this,” he says, his voice more sad than angry, “but I don’t think it’s going to be a tragedy to take Mr. Bonham’s life.” He sounds almost as though he’s talking to himself when he says, “You should walk out with a heavy heart, but with your head held high.

“I’m not going to demean a system Mr. Anderson and I represent by ranting and raving about vengeance.” His face has grown somewhat pallid and drawn; for the first time, I wonder if he truly is sad. Every hero pays his price.

Hardin talks about July 10, 1981, when Tony Bonham visited his parole officer, “acting perfectly normal,” only a day after he had committed murder. “That blows my mind,” Hardin says quietly.

As he paces about the courtroom, emanating disgust, Hardin looks a bit like a boxer who has an opponent reeling on the ropes, helpless; he knows it’s time to stop swinging, that he’s won, but no one has told him so. And so he keeps flailing, but gently, almost kindly, until someone calls a halt to it.

“He has reached the highest rung of man’s inhumanity to man,” Hardin concludes, “at age twenty-one. And society hasn’t done it. Don’t let them put that on you. If the death penalty is to have any meaning . . . can you imagine in your darkest dreams a crime or a background that merits it more? Tony Bonham has been a blot on the soul of society since day one. You have a duty, you really do. You have a duty to all the future victims that exist. And as you do it, I ask you to do it proudly.”

Hardin gestures toward Mr. McGowen. “Look at that face. Let him have another start. Please.”

The jury returns in exactly 22 minutes with a punishment verdict of death. Hardin gives a couple of television interviews and then retires to talk with the jury. It is fascinating, this first truthful session between prosecutor and jury: “What about . . . ?”

“Oh, we couldn’t tell you that,” Hardin says. But then he tells them about the oral confession. The jurors stare at him, mouths agape, as if to say, “Now you tell us.” Indeed, as Hardin rattles off the rest of the evidence that for one reason or another the jury wasn’t allowed to hear, a look of relief crosses their faces: “Boy, I wish you’d told us that back then, but at least we made the right decision anyway.”

“One thing is,” a female juror offers, “that you’re a really great attorney, Mr. Hardin.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” Hardin says. He turns to me. “Let’s go drink.” But before we can get out of the courtroom, another TV reporter corners him and asks him to comment on the verdict. “I’m delighted with it,” Hardin says, smiling.

The drinks are watery and lukewarm and so are the hors d’oeuvres, but nothing can dampen the festiveness of the occasion. We are at the Wooden Nickel. It’s an odd atmosphere, a bit like a locker room after a homecoming game victory. Other prosecutors drop by to offer Hardin congratulations on his fifth death penalty conviction. There is backslapping and horsey laughter, great moments in the trial are replayed, and war stories are traded. We talk some football and some weather. We compare notes on courthouse women. Finally Rusty says, “I wonder what Tony Bonham is thinking about now?” No one answers, and for the first time, the table grows quiet. Someone coughs.

Sometime in the middle of the second round, Rusty’s normally ebullient, grinning face grows hard, then somber. He stares down at his drink and fiddles with a swizzle stick. He glances up at me and says, “Let’s get out of here.” There are more lusty congratulations and handshakes as we leave, and someone repeats a favorite prosecutor’s joke: “Where are you taking Tony to dinner?”

Outside, the air is so cool and silky that it almost makes Main Street in downtown Houston lose its meanness. We walk a couple of blocks in silence and then Rusty says, “In all the years I’ve done this, that’s the one thing I’ve never been able to handle—you know, the celebration . . .” His voice trails off and we walk another block in silence.

“You know, if I could talk to the Maker up there, I sure wish He’d tell me one thing. I wish He’d tell me how I’m supposed to feel now. Happy? I don’t know. Satisfied? I don’t know. If this is the Lord’s work, I sure wish He’d tell me how I’m supposed to feel after I’ve convinced twelve people to kill a guy.” He smiles, but it is a new and altogether different smile.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston