This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

As the gray-haired woman grips the boardroom speaker’s stand, her voice rolls in preacher cadence. “Thank God, thank God for you, Dr. Edwards. I have waited a long time for you,” croons Johnnie Jackson, an officer with the National Congress of Black Women. Another speaker at a black community reception thunders about the biblical significance of Marvin Edwards’ arrival in Dallas. And in the halls of 3700 Ross Avenue—the Dallas Independent School District’s stone-gray administration building—blacks and whites alike have a nickname for Edwards: “The Messiah”; the man picked up by whirling winds from Topeka, Kansas, and dropped from heaven to rescue the DISD from its sins.

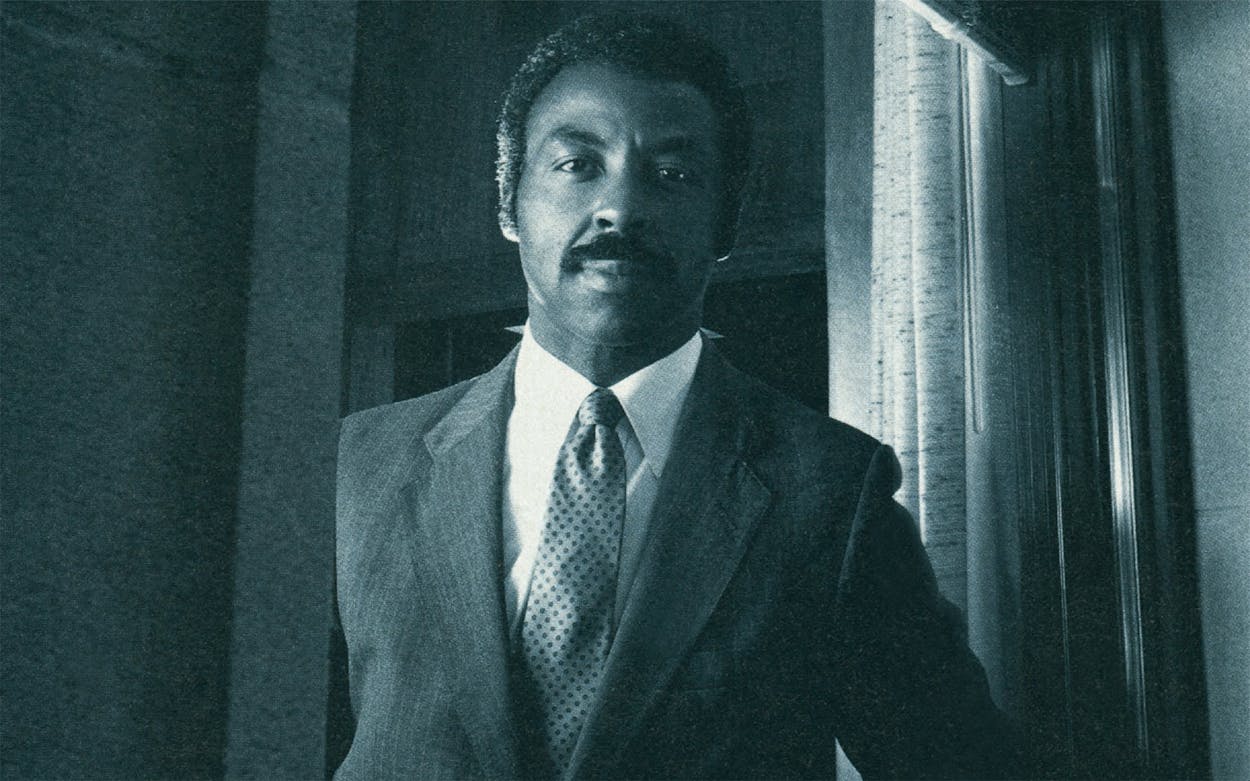

Sitting ramrod straight, legs crossed, dressed impeccably in a crisp white shirt and dark suit, Edwards nods graciously through the speeches and presentations, although he is clearly more than a little uncomfortable with this messiah thing. Edwards is aware that messiahs are not known for lengthy tenure and frequently experience unpleasant ends.

But it’s easy to understand the excitement. The DISD’s fourth superintendent in 43 years is a savvy, bright black man whose hiring has been greeted with acclaim by traditionally antagonistic community factions. The school system sees him as a new commander, with fresh ideas and no political baggage. The black community looks at an 80 percent minority school district and sees one of its own taking charge. The whites look at his low-key style and see a black school manager they can work with. And the DISD board members look at 45-year-old Edwards and see a man they chose unanimously, which is astounding in view of the board’s legendary bickering and racial strife.

Everyone agrees that Edwards is the one man who can wrench the DISD from the depths of its morass, with its high drop-out rate, low achievement scores, hunkered-down administration, in-the-dumps teacher morale, sour public image, and deteriorating facilities. But despite Edwards’ dazzling background and attractive exterior, it has yet to be established whether he can walk on water. Or if, indeed, the school district can be salvaged by whoever sits in the superintendent’s spacious office. The problems facing urban education in Dallas—the eighth-largest school district in the country—are so pervasive that even school supporters have a hard time imagining a significant reversal. While there are bright spots—Atwell Middle School was cited as one of the best in the nation by the Department of Education, for example—the woes at times seem overwhelming.

Dallas’ story is the story of the decline of urban America’s bedrock institution—public schools. The causes vary: too many administrators and too few good teachers, too many broken families resulting in too many undisciplined students, and—one that gets a lot of attention—low expectations from teachers and administrators about minority students.

As has been true in other cities, attempts to desegregate society have been played out most dramatically in the schools. In 1971 Dallas students began being bused. Since 1981 the DISD has been under the jurisdiction of U.S. district judge Barefoot Sanders, who oversees the school system’s policies related to the desegregation order, down to the race of teachers hired.

All these forces have led to disarray in the classroom. Dallas’ scores on achievement tests are among the lowest of any school district in the state. Nearly half of Dallas’ high school students are failing at least one class. The drop-out rate is estimated to be 33 percent. A reading-improvement program designed to close the gap between low-achieving white and minority students at middle schools actually widened it. Teacher morale is the lowest in years. At the end of the school year in May, a middle-school teacher was partially paralyzed after being accidentally hit in the temple with a piece of plasterboard by a student. Teachers were incensed when Robbie Collins, the head of the DISD’s employee and governmental relations, was quoted in the newspaper as saying it was “the price of doing business.”

Hopes now are fixed on the new superintendent, the chief executive officer of the district. Indeed, around the state, with the school reform act of 1984 putting pressure on school districts to perform, superintendents are expected to solve most of society’s problems.

When he took over as superintendent on June 1, Edwards walked into the $125,000-a-year job, overseeing a $636 million budget, 132,000 students, and the second-largest work force in the county. For the first few months, board members tiptoed around him. They talked hopefully about the day when Edwards’ handpicked people would be in place and when the big changes would begin. Any votes that might be perceived as being against his agenda were prefaced with the words, “I reiterate that I support our superintendent, but . . .” Most of them went along—albeit grudgingly—when Edwards led them through an exercise in consensus-building during a one-day board retreat.

In the next two years Edwards is likely to face major issues that could make or break the DISD for years to come. The district will undergo its first accreditation review under the toughened state standards during the 1990–91 school year. Last year the Houston Independent School District was put on “accreditation advised” status by the Texas Education Agency for many of the same problems that plague the Dallas school district. (Houston has since corrected its problems and has been restored to full accreditation. If the district had lost accreditation, it would have lost millions of dollars in state funds.)

And funding also promises to be a big fight. In 1987 state district judge Harley Clark ruled in favor of the Edgewood school district, which had sued state education and government officials and challenged state funding formulas that favor property-rich school districts. How funding will be changed by Edgewood v. Kirby is still uncertain, but Dallas stands to lose a great deal in the redistribution while poor districts would gain.

But Edwards’ biggest challenge will be building a bridge between the black and white communities in a city that has been bitterly divided in the last year. A bid in April by white trustees to declare the DISD unitary, or officially integrated, split the board along racial lines. Though largely a moot point, considering the district’s overwhelming minority student population, the designation of unitary status would remove the district from the jurisdiction of the court, returning control of the district to the school board, thus saving up to half a million dollars in court costs and eliminating delays in implementing programs.

The problem is that although Edwards is black and doesn’t want to upset any of his trustees, he thinks it is inevitable that the district will be declared unitary. And in many other issues on which the black trustees have strong opinions, Edwards does not necessarily hold the same views. Insiders predict that Edwards may suffer the harsh treatment that other black administrators have met at the hands of the black trustees when the administrators differed with them. Says trustee Thomas G. Jones, a 45-year-old black real estate investor and former federal civil rights compliance officer, “Blackness has more to do with attitude than with pigmentation.”

Edwards has a different perspective. When interviewed for his job, Edwards told the board, “If you are interested in hiring a superintendent because of his race, I’m not interested in the job. Don’t hire me because of my race; hire me because I’m competent.”

Edwards’ temperate style sometimes obscures the behind-the-scenes maneuvering of a good CEO. Says one civic leader impressed with Edwards’ strength and abilities, “Some of the members of the board are about to get a healthy dose of reality.”

Bad Manners

It’s a sweltering Thursday night in June, the bimonthly Committee of the Whole meeting of the DISD’s board of trustees, and it’s approaching midnight. A contingent of parents from Edna Rowe Elementary School approaches the microphone one by one. Skirting around words involving race, they talk of problems in the school—of a lowering of academic standards and an extreme lack of discipline among children who are bused in to the residentially integrated neighborhood. Though the group is predominantly white, one woman says they have talked to neighborhood black parents who are concerned about the bused-in students as well.

“All some of them need is a bandanna on their heads,” says Kathlyn Gilliam. She and Yvonne Ewell, both black trustees, take the offensive, asking the parents questions in a badgering tone. Finally, Ewell pronounces judgment: “What I hear is a serious class issue.”

In many ways this is a classic DISD board meeting. It lasts from seven-thirty until after midnight. Board members make speeches and political plays, snipe at the administrative staff and each other, fail to do their homework, go off on tangents, and attempt to ignore state laws (this time by giving teachers raises that would require illegal deficit spending).

There is, however, a guiding principle to the seeming chaos. Practically every issue is defined as a racial issue, with the members of the board falling into predictable patterns. Three black trustees sit on the board: Ewell, a former DISD associate superintendent, usually makes at least one long speech about education, racism, and sexism that everyone ignores; Gilliam, a homemaker, talks about how the district patronizes or ignores black trustees and doesn’t care about minority children; Thomas Jones counts percentages on minority contracts.

Then there are five white trustees: school board president Mary Rutledge, a homemaker who seems chronically unable to lead; Richard Curry, an insurance salesman who, tired of campaigning for state representative, stares off into space, then makes a play for teachers’ support; Betty Vondracek, an interior designer who came up through the PTA, usually just sits passively; Leonard Clegg, an executive at Frito-Lay, grills administrators about fiscal matters, slaps trustees’ hands when he believes they cross the line into the superintendent’s business, and pointedly ignores the black trustees’ comments about racism; and Dan Peavy, a former choral director who manages a family fortune, jokes about his substantial girth, pontificates about the district’s need for more music teachers, and challenges Ewell when she comments on racism.

René Castilla, the board’s lone Hispanic member, who clashes as often with the other minority members as with the Anglo majority, is a professor of journalism and English at North Lake College. Castilla is busy building a power base and getting his name in the paper with, say, a call for a 10 percent reduction in the administrative staff, a popular idea that has no chance of passing.

Lots of personalities, lots of agendas. What seems apparent by one in the morning is confirmed by talking to people in the community: the DISD is in trouble.

Criticism of the district comes not only from outsiders but also from the board members, who have an intimate knowledge of the problems. “We’ve got to have a transformation,” says Ewell, “and it has to be done quickly, before we reach a point of no return.” Community leaders echo her sentiments. “It’s teetering on the brink, ready to slide into the abyss,” says Jean Reeves, an education chair for the Dallas Black Chamber of Commerce.

Such pressure means that effective school superintendents are becoming an endangered species. The average tenure for a superintendent in the 16,000 districts across the country is less than four years. Board members hire a superintendent, and when problems aren’t instantly cured, when test scores stay low, the pressure becomes intense. Houston superintendent Joan Raymond barely survived the 1987–88 school year; two trustees still vow to get rid of her.

The truth about superintendents is that their power, like that of the president of the United States, is limited. In Texas, the Legislature regulates state funding for schools. State statutes govern taxes. Add to that teachers unions, parents organizations, political groups with litigious leanings, and federal court desegregation cases; throw in seven or nine school trustees with as many agendas. The board’s belief that Marvin Edwards alone will be the DISD’s salvation is misplaced. He cannot be the sole difference between success and failure in the school district. The quality of the superintendent, the dollars spent per pupil, the training of the teachers, and the condition of the buildings all play a role in how a district performs. But just as important is the ability of the district’s governing body—the board of education—to arrive at policies that will help kids learn. The attitude set at the top trickles down through the administration to teachers and, finally, to students.

It starts with the board of trustees. And Dallas has a doozy. Their rudeness is not limited to fellow board members—though that would be bad enough. Board members have been known to attack the superintendent, public delegations, and the press. Administrators who must deal with the board develop thick skins and deadpan expressions, or they don’t last long.

Board member Castilla thinks a change is needed. “Something happens to people when they sit at that table,” he says. “They become aggressive; they have no respect for each other. We should be able to disagree but not forget good manners.”

The Long Decline

Things haven’t been civil within the DISD board for a long time. The end of an era arrived in 1968, when W. T. White retired after 23 years as superintendent. White had brought the district through changing times, keeping it fiscally sound, with a solid, if unspectacular, approach to education. White’s successor was Nolan Estes, who was with the federal Office of Education in the years when Lyndon B. Johnson was pumping millions into the public schools.

In 1971 the DISD board was hit with an order by a federal judge to desegregate. The board was seriously divided on the matter of busing; the shouting and name-calling among board members had begun. But Estes was a master politician and knew how to persuade the board members to go his way.

He was regarded in many ways as an innovative superintendent, and his tenure lasted a decade. When he left in 1979, though, what remained was a bloated administration geared toward snooping out federal funds and writing a fancy curriculum as well as a nasty scandal involving misappropriation of DISD funds, which threatened the financial footing of the district.

For help, the DISD looked to Linus Wright, associate superintendent of the HISD. Wright whipped the Dallas district’s books into shape, but he brought in few of his own people, leaving much of the corruption-riddled administration in place. “Linus Wright missed a platinum opportunity,” says Jerry Bartos, a Dallas city councilman. “The community was ready for reform. Linus had good intentions, but no one was there to passionately carry out his plan.”

During Wright’s eight and a half years, the quality of both teachers and curriculum declined. Part of the reason was the women’s movement; as opportunities opened up in other fields, fewer of the best and brightest female college students chose education as a career. Also, teacher pay lagged behind that of other professions, causing teachers to look to new, higher-paying careers. And the curriculum began to become diluted as educators struggled to teach children from various cultures and language groups.

In the eighties dissension on the board grew and became more strident. One reason was the change in 1973 to single-member districts. The much-needed reform opened the way for more minority members on the school board. But as the system became entrenched, one side effect was not so beneficial. Trustees began to see themselves as representatives not of the whole district but of a wedge of it—and their wedge always needed more. With single-member districts also came a reluctance from the trustees to rely on the board president to represent them to the superintendent. Each trustee demanded Wright’s ear and actions on his or her behalf.

But the biggest reason was the change in Dallas itself. White flight left an 80 percent minority district in a predominantly Anglo city. Although the district is 50 percent black and about 30 percent Hispanic, the minorities, especially blacks, see themselves as still underrepresented both in the teaching force and in the administration. (The administration says there aren’t enough black teachers and administrators to recruit; blacks say the effort has been half-hearted.) And despite desegregation and court-ordered busing, black children are achieving less. “Minorities chased a dream across the city, and when we got there, it was a nightmare,” says Ora Lee Watson, a black DISD principal and a former board member.

Minority leaders accuse teachers and administrators of institutional racism, of making promises they don’t keep, and of a subtle attitude that says black and brown students can’t learn, therefore why expect much? In the past year black political frustration has boiled over at the city level, getting national attention, but the same complaints have been going on in the DISD for several years.

The city’s racial polarization is replicated on the board. The three black board members scream racism, and the whites sit back in stony silence lest they be called racist. The white board members cast their votes as a block and maneuver behind the scenes, thus confirming the blacks’ suspicions that no one listens to them.

Racial strife is not limited to blacks versus whites. Last summer black board members were mad at Castilla for voting with the whites on a motion to proceed with the district’s request for unitary status even though he had worked with black member Jones on a compromise draft. After the vote Jones, with tears in his eyes, told Castilla, “You are the enemy. I will never break bread with you again.” And black trustees railed at Otto Fridia, a high-ranking black administrator who served as interim superintendent before Edwards arrived, because he continued to follow many of Wright’s policies.

One result of the strife is that it is hard to get people to run for the board. Dallas has always prided itself on its well-managed civic affairs. The Dallas Breakfast Group, an organization of about seventy successful businesspeople who find and encourage Dallasites to run for city council and school board seats, began looking for someone to run against Peavy in East Dallas’ District 3 last spring. The group went through about ten possible candidates before communications expert Merrie Spaeth agreed to do it. The general response to the inquiries was, Are you kidding?

“It’s very difficult to recruit for the school board,” says Harry Tanner, the executive director of the Dallas Breakfast Group. “It’s almost impossible if the incumbent is going to run.” Sometimes even getting the incumbent to run is difficult. When Clegg, a former board president who had served six years, wanted to retire this year, no one stepped forward to replace him. Reluctantly, he stayed on.

Once people are elected to the board, they tend to find the job too restricting. The current board has a reputation for poking its fingers into the superintendent’s pie. The board’s main functions are to set the school budget and to choose a superintendent to implement the policies the board sets. Admittedly, the line between setting policy and enacting it is sometimes a fuzzy one. And although the board members can approve or disapprove Edwards’ choices, they can’t pick principals or fire administrators.

But several trustees say privately that they do try to do those things and more. “Some of the board members think it’s their job to run the school district,” says one trustee. Indeed, the attitude of several board members is that they should be hands-on trustees. They seem to see themselves as combination policy makers–administrators, like county commissioners. Except for one thing: that’s not their job.

The Only Choice

What is so unusual about the hiring of Marvin Edwards is that such a fractious, fighting, sometimes farcical board of trustees worked together. In the summer of 1987, when the trustees received word that Wright was being tapped for a high-level post in the Department of Education in Washington, D.C., they set ground rules—and followed them. Nobody leaked information to the press for private political reasons. Nobody grandstanded. The board members acted as a cohesive, civilized group of adults, and they unanimously, unequivocally chose the same man. Everyone associated with the school system was amazed.

“It was the DISD’s greatest hour,” says one longtime board observer. He contrasts it with the nasty infighting on the city council that accompanied the hiring of Dallas’ black city manager, Richard Knight. “Marvin Edwards couldn’t have entered the scene better. He was untarnished by the selection process.”

The school trustees had carefully laid out their criteria: experience in a large city, an ability to work with community groups, a willingness to stick around for a while, and, most important, a record of improving student performance, particularly among minority children.

The board members also had a private criterion: They wanted the new superintendent to be black. All other things being equal, the white board members thought that hiring a minority superintendent was a good idea. That would take away one of the minority trustees’ most frequently used weapons, which was charging the administration with racism and running to Judge Sanders for a ruling when votes split along racial lines.

A search committee compiled a list of one hundred candidates and recommended five to the board. Two were white, two were black, and one was Hispanic; all were superintendents of school districts much smaller than Dallas.

Edwards’ interview was last, and the board was immediately impressed. A man who looks as if he were born in a three-piece suit, with a briefcase gripped in one hand, Edwards was, as board president Rutledge puts it, “serious business.” Edwards was a real CEO who was also an educator, a man who had come up through the ranks as a teacher, a principal, and an administrator. For almost five hours the board pounded him with questions, which he answered softly but firmly, with a sure command of the issues, followed by Edwards’ own perceptive questions.

Then the board visited the school districts of four of the candidates (one had withdrawn). The last was Edwards’ district, Topeka, the site of the precedent-setting Brown v. Board of Education desegregation case. The school community, 70 percent white and 30 percent minority, had long been frustrated and fractured. Edwards, the superintendent for three years, had developed a reputation as a brilliant manager and master conciliator. No miracles had occurred, but in that short time he had bridged the gap between the school board and the teachers union, between the majority and the minority communities. Although they didn’t always agree, at least they all talked civilly to each other. A new program for students identified as underachievers was in place and working. The city was proud of its public schools; the mayor, top civic leaders, and several state representatives enrolled their children there.

Edwards did some detective work of his own. Before he submitted his application to the DISD, he checked it out, flying to Dallas at his own expense. Edwards walked the streets downtown, stopping people and asking them what they thought of the city, of the DISD, and of the school board. He even sat in on a school board meeting incognito. He studied the trustees’ interactions and the issues they discussed. He saw their bickering firsthand. When Edwards agreed to come to Dallas, he knew what he was getting into, and it didn’t scare him.

“I felt the board was reacting predictably,” Edwards says. “I do see this as a good working board. It will be a challenge. The division is there, but that doesn’t bother me. Debate is positive.”

During his interview, Edwards told the trustees about his secret visit; they were impressed. To Edwards the up-front detective work was common sense. Four of his five children would be attending DISD schools; he and his wife, Carolyn, would be buying a house and putting down roots. Though moving from Topeka to Dallas would mean a jump in salary and prestige, he wanted to make sure that this was what he and his family wanted. “I spent a lot of time getting to know what to expect,” Edwards says. “I didn’t get any surprises.”

On November 4, 1987, the nine trustees met in executive session. Board president Rutledge suggested they each talk about their impressions of the candidates. After everyone had a say, Rutledge looked around the room and asked, “Do you realize we’ve all talked about one person?” There was no second choice.

The No-Surprises Messiah

Edwards’ nickname, instead of “The Messiah,” might better be “No Surprises Marvin.” He studies personalities carefully; he reads prodigiously. Like a Boy Scout, he is always prepared. He listens, collates, and stores what he hears. “You’ve got to be able to read circumstances and situations far ahead,” he says. Nobody surprises him, and Edwards promises he will never, ever surprise his board. Surprised trustees are dangerous trustees.

What is apparent about Edwards even before meeting him is his unusual gravity. A picture used by Dallas newspapers during the superintendent search shows dark eyes glowering beneath inverted V’s of eyebrows. (The photo used in the board’s brochure shows a more benign Edwards.) A member of one civic group approached Edwards at a meeting and welcomed him to Dallas, mentioning that they both would be living in the same neighborhood. “We should make you a block captain,” the man said, obviously just making conversation. “No, I don’t think so,” Edwards answered seriously. “People take advantage of people with a high profile.” The man continued trying to make small talk, but instead he got a discussion of the need for those in the public eye to have privacy.

Born in Memphis and raised in Danville, Illinois, Edwards is the son of a Baptist minister and a former schoolteacher. After beginning his career as an industrial arts teacher, he moved up rapidly. In 1972, at the age of 28, he became the first black principal of a mostly white high school with 1,300 students in Illinois. By 1978 he was assistant superintendent in Richmond, Virginia, and in 1985 the superintendent in Topeka. He told the Dallas Morning News that his only regret was that he moved up too quickly, leaving jobs that he liked.

His theories on education aren’t wildly innovative. In a speech to the Dallas Homeowners League, he talked of establishing an attitude that all children can learn, of community involvement in education, of teacher “ownership” of programs to increase achievement, and of the importance of holding teachers and administrators accountable.

He carefully downplays the issue of race. “Certain people make it an issue, and many times it’s the media,” Edwards says. “I’m not preoccupied with that as an issue. I think this board will come to work together. We can learn to trust each other, allow ourselves to disagree openly without hidden agendas.”

In spite of Edwards’ rhetoric, something about him is compelling. One DISD administrator uses her grandmother’s old saying to describe him: “He’s a little piece of leather, well put together.” It fits. Edwards is a man who always is in complete control of himself—No Surprises Marvin. But it is safe to say that although the DISD’s new superintendent promises to eliminate the element of surprise, his board won’t.

Taking Over

In the ten months between Edwards’ hiring and the opening of this year’s fall semester, racial tension in Dallas exploded. Black members of the city council and their supporters lambasted the police department over police killings of blacks. At the same time, the police department and its supporters were furious over murders of police officers by citizens.

In early August, several days after a black police officer was shot and killed, DISD board president Rutledge showed what some called a rare display of leadership. She cited the racial tension and called for a postponement of the district’s bid to seek unitary status, an issue some have predicted will signal the end of Edwards’ honeymoon with the board. Earlier in the year the board had voted 6–3, with the black members dissenting vigorously, to hold community hearings and take the case to Judge Sanders by January 4, 1989.

Though Rutledge says the delay was her idea, many believe Edwards was behind the move. Edwards has said that although he thinks the district will eventually be declared unitary, he was concerned about the timing. Black board members supported the delay; two white members went along but said they would not support an indefinite postponement.

The delay bought Edwards more time to put his programs, people, and plans into place before facing a showdown in the boardroom. Several members of the board were disappointed, however, that he brought in only three top administrators instead of sweeping the biggest offices at 3700 Ross clean. In October Edwards made his first major recommendations to the board. He proposed creating a miniuniversity for advanced teacher training, starting a second Montessori elementary school, decreasing the size of some classes at middle schools, and recruiting more bilingual and minority teachers.

“I’ve seen him do some exciting things,” says Harley Hiscox, a DISD board gadfly and the head of United Teachers of Dallas, one of five education-employee groups in the district. “He let the audience talk before the board members—a neat technique that wore the board out. They were too tired to argue with each other. He and Rutledge were in constant conversation. It was a team approach that led to a more controlled meeting. If he continues along that vein, he will take over and become the policy maker, which he should be doing anyway. They’re not competent to set educational policy.”

Edwards doesn’t see himself as the board’s boss. He sees himself as its employee, the only employee it can hire or fire. The key to Edwards’ success or failure, according to DISD watchers, will be how well he is able to define and hold the line between what is his and what is trustee territory.

Judgments on Edwards’ performance are still pending. “He’s serious about doing the right thing by teachers,” says Hiscox. “But he seems a bit overwhelmed by a district this size.” Indeed, if anything was frustrating Edwards’ supporters six months after he took over, it was that the superintendent still operated with the hands-on management style that had worked in the much-smaller Topeka district but was impossible in Dallas. And on the board, the old tension is starting to resurface. Meetings are getting more vitriolic, and several of the board members have recently chastised Edwards.

But Edwards has continued something he started the day he became superintendent: He is bringing his agenda to his constituents. Taking advantage of the postponement on the district’s bid for unitary status, Edwards planned to meet throughout the school year with parents and other school officials about the issue. “Business as usual won’t cut it anymore,” says one Edwards supporter. “If Dr. Edwards goes public, the city will rally around him.”

Although Edwards doesn’t promise any miracles, he predicts that in two years Dallas will see major improvements in the school district. If he is right, his impact on Dallas will be enormous. Dallas is at a crossroads; the city government is stumbling. As the superintendent of a huge institution where all the races come together, Edwards can provide leadership that will mean students who not only can read and write but also will provide direction for Dallas years from now.

He has made it clear in all those speeches, receptions, and breakfast meetings that it is up to Dallas to get behind him. Edwards has been going beyond the board, to the people who elect its members. After laudatory speeches by black leaders in June, Edwards came to the podium. “If we’re going to be successful, it’ll be because you get behind it,” he said. “I’m happy to be your orchestra leader. You all have a part to play.”

Glenna Whitley is a freelance writer living in Dallas.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Public Schools

- Longreads

- Dallas