If you haven’t seen Darlie Routier since she was sent to death row five and a half years ago—if your only memories of her are the glamorous photos, when her hair was platinum blond, her face was caked with makeup, and her fingers were covered with diamond rings—you might not recognize her today. She is now 32 years old. Her hair is long and chestnut brown and pulled away from her face, accentuating her cheekbones and bright hazel eyes. Her body is toned, thanks to a daily workout regimen of five hundred sit-ups in her cell and a vigorous two-hour walk in the prison yard. When she takes her seat behind the shatterproof glass in the visitors area of the Mountain View Unit, in Gatesville, she smiles pleasantly, rests her elbows on the table, and with a soft giggle says that she has been reading the latest Harry Potter book so she can talk about the plot with her youngest son, Drake, age six, the only one of her children who is still alive.

She receives a constant stream of visitors: friends and family, lawyers, journalists, and private investigators. They study her the same way the crowds at the Louvre stare through a sheet of bulletproof glass into the enigmatic eyes of the Mona Lisa. They listen to her talk in her light, sugary voice about the sympathetic letters she receives from other parents who have lost their children; about her prison job cross-stitching baby blankets that are later sold to state prison employees; about the stories that she reads in Parenting magazine, which she receives every month; and about her disbelief that she is still in prison. “Why is this happening to me,” she says with a catch in her throat. “Why is it so hard for people to see the truth?”

On June 6, 1996, Devon Routier, who was six, and Damon, five, were murdered as they slept on the ground floor of the family’s well-kept brick home in Rowlett, a suburb east of Dallas. Devon was stabbed twice in the chest with such force that the knife almost went all the way through his body; Damon was stabbed half a dozen or more times in the back. Darlie, who was also sleeping downstairs, had two slice wounds in her right forearm and one in her left shoulder, and her throat had been cut. Doctors said she survived only because the knife stopped two millimeters short of her carotid artery.

In a written statement given to the police a few days later, Darlie, then 26, told the following story: She was awakened by Damon’s cries of “Mommy! Mommy!” In the dark, she didn’t even notice she was hurt. She saw a man moving through the kitchen and followed him as he went toward the garage. When she got to the utility room, she saw a knife and picked it up. Only then, she said, did she return to find Devon and Damon and realize that she had been stabbed too. Darlie’s husband, Darin, who was sleeping upstairs with their infant son, Drake, came downstairs after hearing his wife’s screams and began administering CPR to Devon. By then, the assailant had disappeared.

Twelve days after Damon’s and Devon’s deaths, the police arrested Darlie for their murders. They had no eyewitnesses, no confession, and no motive. What they did have was an intriguing trail of circumstantial evidence that suggested there was no intruder that night; physical evidence suggesting that Darlie had staged the crime; doctors’ statements suggesting her wounds were self-inflicted; and a peculiar scene caught on videotape a few days after the murders. On what would have been Devon’s seventh birthday, Darlie drove to the cemetery with family and friends, wished her son a happy birthday, and then sprayed Silly String all over his grave. “Here’s a mother who has supposedly been the victim of a violent crime,” said Dallas County assistant district attorney Greg Davis, the lead prosecutor in the case. “She has just lost two children, and yet she’s out literally dancing on their graves.”

Within eight months of the crime, Darlie was convicted and sentenced to death by a jury in the Hill Country town of Kerrville, where the trial had been moved. She seemed destined to be remembered as yet another stressed-out mother who had suddenly spiraled out of control. Three true-crime paperbacks, published in the year after her conviction, characterized her as the embodiment of evil. But over the years, numerous news stories and an ongoing investigation by Darlie’s appellate attorneys have raised questions about what really happened that night: Could it be that the police and the prosecutors manipulated the evidence to implicate someone they decided must have done it? A growing chorus of observers of the case believes so. At least half a dozen Web sites have been set up to proclaim Darlie’s innocence (one of them, fordarlieroutier.org, has received more than seven and a half million hits since January 2000). A juror from her original trial now says that he and his fellow jurors made the wrong decision. The author of one of the true-crime books has also changed her mind, claiming the jury heard perjured testimony and was never shown photos that would have proved Darlie was a victim of a savage attack.

Even the most experienced legal hands have found themselves sucked in by the Routier saga. This past March, in oral arguments before the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals into whether procedural flaws were made during the original trial, the nine judges began peppering lawyers with questions on other aspects of the case. Was there an insurance policy on the children, which might have given Darlie a reason to kill them? When Darlie talked to homicide detectives, did she make any kind of confession? As the hearing ended, one of the more curious judges motioned to me and asked me to point out Darlie’s mother, Darlie Kee, who had made headlines of her own for her passionate attacks on an assistant district attorney, and Darlie’s husband, Darin, a headstrong machinist’s son who, after the trial, had likenesses of his wife and their three boys tattooed on his right arm.

This month, with Darlie’s defense attorneys set to file a writ of habeas corpus that claims new evidence proves her innocence, the debate is going to get even more heated. Darlie’s lead appellate attorney, Stephen Cooper, has announced that an analysis recently conducted by one of the country’s most respected forensic anthropologists determined that a bloody fingerprint found on a glass table in the room where the murders took place does not, as the prosecutors contended, match either of the boys. Nor does it match Darlie, Darin, or any of the investigators or emergency workers who were at the house that night. It almost certainly belongs to an unidentified adult, bolstering the defense’s theory that someone broke into the house.

But the most startling new piece of information, one that has never been publicly revealed before now, could very well answer the most baffling question about the murders: Why would someone show up in a nice new suburban neighborhood, target a house on a well-lit cul-de-sac, enter through a garage window a few feet from a dog’s cage, navigate his way through a darkened utility room, grab a butcher knife from the kitchen, and then head into the living room to stab two boys and slice their mother’s throat? Although several neighbors told the police that they had noticed a dark car slowly cruising the area in the weeks before the crime—one even said that the car occasionally stopped near the Routiers’ house—veteran investigators never believed that Darlie and her sons were the victims of a random attack by a stranger. Nor were they able to find anyone who had a reason to harm them.

Yet according to Richard Reyna, a private investigator working for Darlie’s appellate attorney, Darin Routier admitted last year that in the spring of 1996, when his business was in trouble and he was $22,000 in debt, he had asked Darlie’s stepfather, Bob Kee, whether he knew anyone who might break into the family’s house as part of an insurance scam. Once the furniture and other items were “stolen,” Darin would retrieve them from the “burglar” and pay him out of the proceeds from his insurance claim.

A couple of months ago, when I asked Darin if he had made such a statement, he denied it. But a few days later, when I confronted him with affidavits given to me by Darlie’s stepfather and Reyna, he confessed that he had, in fact, talked to Kee about faking a burglary. When I asked if he had discussed the plan with anyone else, including a couple of reputed car thieves in Rowlett, Darin hesitantly replied, “There is a possibility I said the same thing in conversation with people that worked around me. I don’t remember what I said. But there’s a strong possibility that was on my mind, and in conversation I could have said that.”

Darin insisted that he never carried out the plan, and Reyna said he has found no evidence to the contrary. The prosecutors who tried the case against Darlie chuckled when I told them about Darin’s story, noting that it was suspicious that he would go public just in time for the filing of the writ. They said that Darlie’s lawyers might be using me to get favorable publicity for their client while the Court of Appeals is considering her case. Anyway, they said, if someone really did break into the house to burglarize it, why didn’t he grab some of Darlie’s jewelry, which was sitting in plain view on the kitchen counter? Why grab only a butcher knife and commit murder?

Darin’s reluctant admission certainly raises more questions than it answers. But it also suggests some tantalizing what-ifs. If, for instance, Darin’s fake burglary scheme had come out before Darlie’s trial, prosecutors might still have gone after her but probably would not have sought the death penalty in what would have been a tougher case to make. Darlie’s defense lawyers surely would have used that admission to create reasonable doubt as to her involvement, perhaps leading to her acquittal, regardless of whether she was guilty. Most significantly, if Darin’s admission leads to additional confessions about a break-in at the Routier house, it could well prove what Darlie has been saying all along: that she did not kill her kids.

The Clampetts or Ozzie and Harriet?

Every detail of Darlie Routier’s life has been thoroughly examined by reporters, investigators, lawyers, and cops. Academic treatises on maternal filicide have been reviewed again and again to see if any case compares with hers. Yet even now, no one has been able to come up with a plausible explanation as to why she would have stabbed her boys. Unlike Andrea Yates, Darlie had no history of mental illness or psychotic hallucinations. Unlike Susan Smith, the South Carolina mother who drove her kids into a lake, she had no abuse or incest in her background. She had no criminal record, and she was not known to have committed adultery.

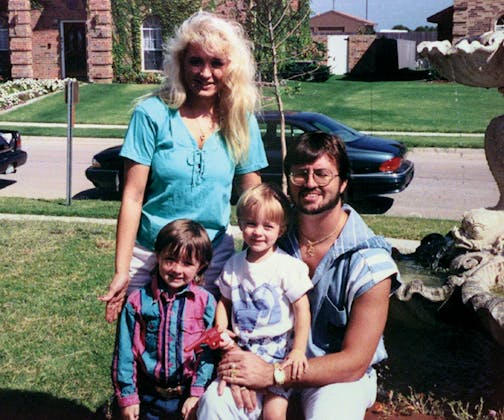

Born in Pennsylvania, Darlie moved to Lubbock as a teenager with her mother and stepfather. She met Darin at a Western Sizzlin’, where he worked as a cook (her mother waited tables there). The seventeen-year-old boy was immediately infatuated with the bubbly fifteen-year-old girl with the frosted hair. “She was different than anybody I had ever met,” Darin recalled, “a trendsetter on her own path.” They married four years later in the garden room of his parents’ house. He had been voted most likely to succeed at the small high school he had attended on the outskirts of Lubbock, and he planned to prove it. After moving to the Dallas area, he started a small company that tested electronic components, and when he began making money in the early nineties, he and Darlie cut loose. They bought a $130,000 house, adding marble in the bathroom, white carpet in the dining room, and $12,000 worth of drapes in the living room. They bought a $600 fountain for the front yard and a $9,000 redwood spa for the back. Darin purchased a thirty-foot cabin cruiser to use on nearby Lake Ray Hubbard and a 1982 Jaguar to drive to and from work. When Darlie’s beloved cat died, she spent $800 for a tombstone to put over its grave at a pet cemetery.

In 1995 Darin’s company brought in about half a million dollars in gross revenues, and he paid himself an annual salary of $125,000. “At the time, we were in the top two percent of the tax bracket for our age,” he told me more than once. And they spent every cent they made. Their neighbors thought they were a hoot, Rowlett’s version of the Clampetts from The Beverly Hillbillies. Darin wore shirts with the sleeves rolled up to show his muscles, grew his hair long in the back, and sported a diamond watch and gold-nugget-and-diamond rings. Darlie got size 36 DDD breast implants that she showed off in tight-fitting tops, made regular visits to the tanning salon, and wore diamond rings on every finger. She bought a toy Pomeranian with white hair matching her own.

Even if they were a little flashy, they were not disliked; one neighbor called them the “Ozzie and Harriet of the nineties.” Darlie was known as a cookie-baking housewife who always let the neighborhood kids hang out at her house, which they called the Nintendo House because of the elaborate game room that Darin had designed. (After her arrest, several of those kids put signs in her front yard proclaiming her innocence.) She cooked for neighbors going through hard times and even made a mortgage payment for a neighbor with cancer.

In early 1996 Darin’s business began to suffer, and he got behind on the bills; he was at least a month late on the mortgage and owed $10,000 in back taxes to the IRS and $12,000 on credit cards. But if the financial problems were causing stress in their marriage, no one in the neighborhood saw it. Darin decided to start a second business, called Champagne Wishes, in which he would take people around the lake on his boat at sunset while they sipped champagne and, if they wished, used the boat’s bedroom. Darin’s difficulties didn’t seem to concern Darlie either: Her shopping never slowed, and she made plans to take a trip that summer to Cancun with some friends.

The Routiers’ neighbors thought they were a hoot. Darin wore shirts that showed his muscles. Darlie got size 36 DDD breast implants that she showed off in tight-fitting tops.

But on May 3, about a month before the murders, Darlie made an unusual entry in her otherwise upbeat diary. “I hope that one day you will forgive me for what I am about to do,” she wrote. “My life has been such a hard fight for a long time, and I just can’t find the strength to keep fighting anymore.” On that day she considered taking some sleeping pills to kill herself. But she never took them and never finished her diary entry. After talking with her on the phone, Darin became worried and came home to comfort her. At that point, she told me, she was ashamed of what she had done and never thought about taking her life again.

Darlie said her “blah feeling,” as she put it, was because she hadn’t gotten her period in more than a year. When it arrived a few days after her suicidal thoughts, she said, her spirits soared. In fact, people who saw her in the weeks that followed say she did not seem particularly despondent. Her old friend Barbara Jovell did tell Darlie that she should get some counseling or perhaps enter a treatment center, as she herself had done when she once felt suicidal, but Jovell didn’t sense that Darlie was desperate or self-destructive. And she certainly didn’t act differently. In late May Darlie and Darin took the boys to Scarborough Faire, a festival featuring characters dressed in medieval costumes. Darlie, flamboyant as always, wore a silky belly-dancing outfit.

On June 5 the boys played in the hot tub, and that evening Damon and Devon huddled under blankets in front of a television Darin had just installed in the living room. Darlie and Darin would later say they stayed up talking past midnight, then kissed each other good-night. Darin went upstairs to the master bedroom, where Drake, then seven months old, was asleep, while Darlie curled up on the couch downstairs next to the two older boys. She had been sleeping on the couch that week, she said, because she wanted to watch over Damon and Devon, who had been spending the night downstairs since school let out, and because she was a light sleeper and would sometimes be awakened by Drake turning over in his crib.

A few hours later, a 911 dispatcher in Rowlett received a frantic call. “Somebody came in here,” Darlie screamed. “They just stabbed me and my children!”

The Case Against Her

The first tip-off for the cops was the 911 call. Why, in the midst of that craziness, did Darlie feel the need to tell the dispatcher that she had picked up the butcher knife, that her fingerprints were on it, and that she hoped they would still be able to get the prints of the attacker? One of the first officers at the scene was also perplexed that Darlie didn’t tend to her sons, even when he asked her to. Instead she held a towel to her own neck. Nurses at the hospital where Darlie was taken said that when she was told that her sons were dead, she exhibited a “flat affect” and did not dissolve into hysteria, as mothers often do upon learning they have lost their children.

After the murders, Darlie gave conflicting accounts of what exactly the intruder had done to her. One officer said she told him that she had struggled with her assailant on the couch. Another officer said she told him the struggle was at the kitchen counter. A friend who talked to Darlie while she was in the hospital said Darlie told her that she remembered lying on the couch as the man was running the knife over her face—but in her formal written statement to the police, Darlie said her only view of the man came as he was walking away from the couch. She said she just couldn’t remember any distinct details about the attack or the killer except that he was wearing dark clothes and a baseball cap. Was it really possible that Darlie, who could be awakened by her baby moving in his crib, had slept through the stabbings of her sons a few feet away?

The cops’ suspicions grew when the doctors and nurses who treated Darlie told them that her wounds could have been self-inflicted. Then, a few days after leaving the hospital, she showed the police dark bruises that covered her arms from wrist to elbow. Yet the doctors who examined her said the bruises were too fresh to have been inflicted on the night of the attacks. More likely, they said, Darlie hit her arms with a blunt instrument after she left the hospital—or had someone else do it—to convince the police that she had been attacked.

After studying the crime scene, the police noticed that the so-called intruder had apparently gotten into the house by slashing a window screen that covered a low garage window, then stepping through the slit. Why, the cops asked, didn’t the intruder just pull off the screen, as burglars normally do? Why did he only slice Darlie’s throat and stab her in the shoulder and forearm instead of plunging his knife deep into her body the way he plunged it into the bodies of her boys? Why not make sure that Darlie was dead so that she would not be able to identify him?

To evaluate the veracity of Darlie’s story, a forensics expert tried to replicate the intruder’s series of moves, dropping a bloody knife from waist height onto the utility room floor while making his way toward the garage door. The blood spattered across the floor in a pattern that looked entirely different from the little pools found in the utility room the night of the murders. When a chemical called Luminol was sprayed around the kitchen to reveal traces of blood not visible to the naked eye, bloodstains were discovered in the sink, the kind that would be consistent with someone washing blood off his or her hands. There was also an indication that some of Darlie’s blood around the sink had been wiped up with a towel. In her various statements to the police, she had never mentioned standing by the sink. Was it possible that she had cut her own throat at the sink and then tried to wipe up the blood?

When another blood expert found tiny drops of the boys’ blood on the back of the Victoria’s Secret nightshirt that Darlie had worn that evening, he remarked that a likely way the blood could have gotten there was when it dripped off the butcher knife and onto Darlie’s back as she was raising her arm above her while stabbing the boys.

Then Charles Linch, Dallas County’s premier trace-evidence analyst, dropped a bombshell: He said that he had found a bread knife in the kitchen that contained a nearly invisible fiber, sixty microns long, made of fiberglass coated with rubber. Under a microscope, Linch had determined that the fiber found on the bread knife looked exactly like the fiberglass in the window screen cut by the intruder. Was this the knife used to cut the screen? If so, only someone already inside the house could have cut it. And because Darin’s story—that he had run downstairs and given CPR to Devon until an officer arrived—was consistent with the physical evidence, the police were left with a single suspect: Darlie.

The Case Against the Case Against Her

There was just one problem. On the night of the murders, one of Darin’s socks was found down a back alley some 75 yards away from the house. It contained two small spots of blood from Damon and Devon but none of Darlie’s blood. What was the sock doing there? Police initially speculated that Darlie had carried the sock three houses away to make it look as if the intruder had dropped it during his escape. But they could find none of Darlie’s blood—or anyone else’s blood—outside the house. There was no blood on the back patio or the back fence or in the back alley. If Darlie had planted the sock, how did she avoid leaving a trail of her own? Once her throat was cut, she lost significant amounts of blood.

The detectives and the prosecutors came up with an interesting theory: Darlie stabbed her boys to death, ran the sock down the alley—perhaps to give the impression that the intruder had used it to keep his prints off the knife—then cut herself at the kitchen sink. Either before she stabbed the boys or before she stabbed herself, she cut the window screen with the bread knife. Once all that was done, she called for Darin and then called 911.

But if Darlie wanted the cops to find the sock, wouldn’t she have thrown it closer to the house, perhaps at the end of the driveway, instead of leaving it so far away, next to a garbage can where the police might have overlooked it? And wouldn’t she have doused that sock in blood so the police would know what they had found? And even then, would Darlie have had time to do everything before the police arrived? Records indicate that Darlie was on the phone with the 911 dispatcher for five minutes and 44 seconds. Just as that call was ending, a police officer came inside the house, and he was there for at least a minute before the paramedics arrived. The paramedics found Damon still breathing; he died shortly thereafter. Why is that important? According to a doctor who studied the severity and location of Damon’s stab wounds, the boy could not have lived longer than nine minutes once he was first stabbed and probably lived no more than six minutes. Let’s assume he lived nine minutes. If you subtract from that nine minutes her five-minute-and-44-second phone call to 911, then subtract the additional minute and 10 seconds that she was in the presence of a police officer, Darlie had only two minutes and 6 seconds to stab her sons, head for the garage, step through the slit in the window screen, jump a back fence or go through a back gate, run barefoot for 75 yards down an alley, drop a bloody sock, run 75 yards back, stab herself, clean up the blood around the sink, and stage whatever crime scene there was left to be staged.

The prosecutors did not have a good answer to the timeline conundrum except to say that the doctor was simply guessing about the nine minutes it took Damon to die and that even then Darlie could have had enough time to commit the murders and stage the crime scene. But if she was smart enough to plant fake evidence, wouldn’t she have been ready with a more believable story about what the intruder looked like and how the killings occurred? Would she have been so stupid as to tell the police that she slept through the attacks and that she could not remember what had happened?

If Darlie is indeed a calculating murderer, wouldn’t she have made sure both boys were dead before she called 911 so they could not finger her as the attacker? Wouldn’t she also have made sure to get rid of her diary so that the cops wouldn’t see her suicidal musings? Wouldn’t she have made sure to weep at the hospital so that the nurses would see the depth of her grief? And when she went to the cemetery on Devon’s birthday in the presence of television cameras, wouldn’t she have made sure to turn on the tears instead of singing and spraying Silly String?

What really made no sense was why she would choose Damon and Devon to kill. If Darlie, as the cops and the prosecutors believed, had become increasingly upset about money, why didn’t she murder Darin and cash in his $800,000 life insurance policy? The policies on Damon and Devon totaled only $10,000, and their funerals alone cost more than $14,000. If she was overwhelmed by the stresses of motherhood—another theory—then why didn’t she also kill Drake, the baby, who required most of her attention?

At her trial, Darlie’s lawyer, Doug Mulder, one of Dallas’ most prominent and charismatic criminal defense attorneys, kept asking the jurors if they really believed that a doting mother could, in the course of a single summer night, pop popcorn for her boys, watch a movie with them, and then suddenly snap and turn into a knife-wielding nut. A psychiatrist who had interviewed Darlie for fourteen hours after her arrest said she was telling the truth about the attacks and that her loss of memory about certain details that night was the result of traumatic amnesia, which can occur following emotionally overwhelming events. Vincent DiMaio, the chief medical examiner in San Antonio and the editor-in-chief of the prestigious Journal of Forensic Medicine Pathology, testified that her injuries were not at all consistent with the self-inflicted wounds he had seen in the past; he said that the cut across her throat, in particular, was hardly “superficial,” as the prosecutors alleged. Mulder produced notes taken by the nurses at the hospital that said Darlie was “tearful,” “frightened,” “crying,” “visibly upset,” and “very emotional” on the night she was brought in. Finally Darlie herself took the stand, explaining that she had stood at the kitchen sink to wet towels and place them on her children’s wounds and that the Silly String scene was her heartfelt way of wishing a happy birthday to Devon, who she hoped was watching from heaven.

Darlie, however, was not a persuasive witness. She cried at odd times and became far too defensive under the cross-examination of Toby Shook, the veteran Dallas County prosecutor who kept slamming her for what he called her “selective amnesia.” One of the prosecution’s expert witnesses aggressively promoted the theory that Darlie was guilty, and in the end, the evidence, however circumstantial, was too much for the jurors—even if they never could figure out how the bloody sock got down the alley. During their deliberations, they watched the Silly String video a reported seven times. Perhaps Mulder made a mistake in not introducing another videotape secretly recorded by the police that showed Darlie weeping over her sons’ graves. Perhaps the outcome would have been different had he found more expert witnesses to counter the prosecution’s experts. But even then, it’s hard to see how a jury would have gotten over the finely honed image of Darlie as a mentally unbalanced, gum-chewing bleach blonde who seemed to be unmoved by, if not outright exhilarated over, the deaths of her children.

Scenarios

In the years since Darlie’s conviction, various well-wishers have attempted to prove her innocence. A writer in the Dallas suburb of Lewisville who published a book on the case told reporters that he believed the killer was the son of a Rowlett police detective. A Waco millionaire, Brian Pardo, reportedly spent $100,000 on an independent investigation of the murders, conducting handwriting analyses and other tests on Darlie. He also persuaded Darin to take a lie detector test administered by a Waco police officer. Pardo told reporters that Darin was shown to be lying when he answered no to four questions: Was he involved in any plan to commit a crime at his house on June 6, 1996? Did he stab Darlie? Did he know who planted the sock in the alley? Could he name the person who stabbed Darlie? Darin did not deny that he failed the test but told me that he was manipulated by the examiner, who he said spent two hours upsetting him with “a million questions” about the murders before hooking him up to the polygraph. Darin also speculated that he was suffering from survivor’s guilt, in which he envisioned himself at the scene trying to help the kids but was unable to reach them. (According to knowledgeable sources, Darlie too was given a lie detector test by one of her original court-appointed attorneys. The attorney refuses to comment on the results, which have never been made public.)

Polygraph tests are not admissible in court, so they proved of no value to Darlie’s court-appointed appellate attorney, Stephen Cooper. But Darin intrigued him. Beginning in 1998, operating out of a cluttered office near downtown Dallas, Cooper gulped down coffee and smoked cigarettes as he worked nonstop on the case, eventually covering his floor with more than 25 boxes of Darlie-related files. Last year Cooper filed his first brief with the Court of Criminal Appeals to get Darlie a new trial. Among his many claims: conflict of interest by Doug Mulder. Cooper said Mulder should have raised questions before the jury about Darin’s potential involvement in the murders but couldn’t because, for a single day before taking on Darlie as a client, he had represented Darin and Darlie’s mother at a pretrial hearing over a gag order. Cooper alleged that Mulder could have learned something from Darin about what had really happened that night but was unable to use it because of his loyalty to a former client. This is important, according to Cooper’s brief, because Darin was a plausible suspect. He not only had a pecuniary motive to get rid of Darlie—her life insurance policy cashed out at $200,000 to $250,000—but he had the means and the opportunity to commit the crime. Darin, said Cooper, could have slashed the window screen and then carried the sock out to the alley without leaving a blood trail, because he had not been stabbed himself.

Mulder recently told me that he had represented Darin for less than an hour that day and that Darin told him nothing about the murders. Mulder said that he would have quickly and happily pointed the finger at Darin but that every time he asked Darlie if her attacker could possibly have been her husband, she said, “Absolutely not.” I asked Mulder if he had ever heard a rumor, while preparing for trial, that Darin was looking for someone to burglarize the house before the murders. “Never,” he said.

But according to the affidavit given to me by Darlie’s stepfather, Bob Kee, Darin said in the spring of 1996 that he had a plan in which he and his family would be gone from the house and that a “burglar,” hired by him, would pull up with a U-Haul truck, remove household items, and keep them hidden until the insurance company paid the claim. All that was needed, Darin said, was someone to do the job.

The soft-spoken Kee, who lives with Darlie’s mother on a small farm east of Dallas, told me that when the murders first happened, his conversation with Darin “never crossed my mind.” When I asked him why he didn’t later get the information into the hands of Darlie’s lawyers, he said, “I don’t have a good answer other than ‘I don’t know.’ ” Maybe he didn’t want to get Darin in trouble—or maybe, as implausible as it seems, he failed to make a connection between Darin’s plan and the murders. Darlie’s mother, Darlie Kee, told me that she had never wanted to consider the possibility that Darin was involved; she loved him like a son. But in March 2000, after Darin seemed to be getting increasingly upset over questions from Richard Reyna, Cooper’s private investigator, she began to have second thoughts, and her husband told her for the first time the particulars of his long-ago conversation with Darin. She immediately called Stephen Cooper.

Could Darlie’s husband, mother, and stepfather be making the whole thing up to help her get a new trial? Reyna grilled Darin repeatedly about the story and said he believes Darin was looking for someone to hire. He said he even got Darin to admit to him that he had worked out another scam a couple of years before the murders in which he had had his car stolen so he could collect the insurance money. Darin told me that he did not arrange for his Jaguar to be stolen, but he admitted saying to the person who he believed eventually stole the car, “It wouldn’t bother me if it was gone.”

If Darin’s fake burglary scheme had come out before Darlie’s trial, her lawyers surely would have used it to create reasonable doubt, perhaps leading to her acquittal.

Darin would not deny to me that the person who broke into his house and murdered his sons could have been someone who had heard him discuss his would-be insurance scam. But he said he had no idea who that person might be—and if such a crime did happen, it was without his assistance. “Why would I do that if I had my kids and my wife downstairs?” he said. “That’s the craziest story I have ever heard.” When I told him that the complete truth might help get his wife a new trial, he insisted that he wanted to do what he could for Darlie. “But I don’t want to end up with some kind of bullshit charges brought against me either,” he said. “I don’t want to help her at the expense of my life.”

Reyna said he wonders if Darin is holding back even more secrets. After interviewing both Darin and Darlie, he got the idea that Darin might have hired someone to kill her. He said Darlie told him that she had been threatening to divorce Darin—a fact that has never been made public. He said Darin was once so upset over Darlie’s threat of divorce that he had put a pistol to his head. Was it possible that Darin had decided that if he was going to lose Darlie, he wasn’t going to let anyone else have her?

Darlie told me she was never serious about divorcing Darin. Only once, added Darin, did she pack a suitcase and spend the night with a girlfriend “because she thought I was working too much and not showing her enough attention.” The pistol incident—which Darin characterized as “dramatic bullshit to get her attention, like she does to me all the time”—happened two full years before the murders. “Me and Darlie, we’ve had our spats, but it’s never been serious,” Darin said. “I’ve never hit her. I’ve never cheated on her.” When I asked him about Reyna’s suggestion that he would want Darlie killed, Darin replied in a disgusted tone of voice, “That’s completely false and ridiculous.”

Here’s where the what-ifs come into play. What if Darin is lying and really did hire someone to kill Darlie? Once he realized Damon and Devon were sleeping downstairs a few feet from their mother, wouldn’t he have called the thing off rather than risk the lives of his sons?

What if Darin hired someone to break in, with no intention of anyone getting killed, only the “burglar” showed up on the wrong night? When he encountered Darlie and the boys asleep downstairs, wouldn’t he have turned tail and run? Would he really have panicked, picked up a sock from the utility room, wrapped it around his hand to avoid leaving fingerprints, grabbed the butcher knife, stabbed the boys, slit Darlie’s throat, and run quickly out the back, along the way dropping the knife in the utility room and the bloody sock in the alley?

What if there never was an outside intruder after all? What if Darlie really did it and Darin was her accomplice in covering it up—a scenario that prosecutors say they have also considered? What if Darin came downstairs, saw what his wife had done to the boys, and then planted false clues to try to keep her from being arrested? Because he had no blood on him, he could have taken the sock down the alley without leaving a trail. He could have been the one who carefully cut Darlie’s throat and inflicted her other wounds, after convincing her that the cops would be more likely to believe her story if she had also been stabbed.

Or maybe Darlie, who was in such a delicate emotional state only a month before, decided after one of her fights with Darin to murder the boys and then kill herself—only she couldn’t quite bring herself to commit suicide. Perhaps Darin came downstairs, begged her to put the knife down, and then planted false clues and staged a crime scene before having her call 911.

Darin said all the speculation is outlandish and that he still believes an unknown assailant came into his house. “I love my wife and I loved my boys,” he told me. “My God, I loved them.”

“How did this ever happen?”

While Cooper prepares the appeal of Darlie’s conviction—focusing not just on inconsistencies in evidence but on procedural problems in the first trial, including an amazing 33,000 errors made by the court reporter in the original trial transcript—she sits quietly in her cell on death row. According to prison officials, she is a well-behaved inmate. She discusses questions about her case in a calm, thoughtful manner. At Cooper’s request, she does not talk about any of the latest revelations regarding Darin except to say that when Darin last visited her, she begged him to divulge everything he knows about what happened that night. When I ask her if her marriage is going to survive, she pauses, then says, “I don’t know. I don’t know what to think about Darin anymore.”

She then tells me that rarely a minute goes by that she does not think about her children. She wonders what Damon and Devon would look like if they were still alive. She wonders what it would feel like to hug Drake. She wonders how it would feel to be strapped to a gurney in the death chamber at Huntsville. “Not too long ago,” she says, “I was going through [photo] albums of my boys, and I looked up. I was sitting on this cement floor in my cell, and there was this stainless steel potty across from me and these dull, gray-looking sheets on the bed, and it’s like, ‘How did this ever happen?’ ”

For a moment, she raises her head the way people sometimes do to prevent tears from welling up in their eyes, then flashes a gentle smile. Perhaps she’s trying to show me, as she shows all her visitors, that she’s just as sweet as she was back in Rowlett. Perhaps she’s trying to show me that even if she once did something very, very bad, she’s still, deep down, capable of being good.

She smiles again and tells me about the pattern of a baby blanket she’s cross-stitching. There are two angels nestled next to a teddy bear, and at the top it reads “Angels Are Watching Over You.”

“It’s going to be beautiful when it’s finished,” she says.