This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Late one evening last May Houston city councilman George Greanias picked up the phone in his Montrose home to tell Mayor Kathryn J. Whitmire that he had done what she wanted. All day long Greanias had hustled around city hall, trying to round up enough votes to push a tax increase through the city council. Greanias had volunteered for the mission the evening before, when he had stopped by Whitmire’s home and sensed that the mayor was waffling on his pet project, indeed, on the thing he cared most about as a councilman: a plan to include a small property tax increase in her 1984–85 budget.

In his two and a half years on the council, Greanias had become convinced that Houston needed a tax increase. As he saw it, an increase was the only way to get any immediate improvement in the city’s legendarily poor services. During the previous year’s budget deliberations, Greanias and a few council allies had pushed for better services, but Whitmire, a strong-willed mayor operating in a system that favored strong mayors, had ground them down. After that defeat, Greanias began talking like a football fan whose team has finished out of the play-offs. Next year, he kept saying, next year. Now, next year had come.

For months Greanias had been whispering in Whitmire’s ear about the need for the tax increase in the new budget, scheduled to take effect on July 1. For her part, the mayor had seemed at least open to the idea, and at times Greanias thought she was genuinely in favor of it. But she had her own set of concerns, and the day before, she had posed her big question to Greanias. If she went along with the tax increase, could he guarantee that the budget would pass quickly? Whitmire cared a lot about getting the budget passed on time—it was as much her obsession as a tax increase was Greanias’—and it seemed that there might be a trade in the works: the tax increase and the services the council members wanted in return for a smooth and efficient budget process. Greanias leapt at the prospect, hence his attempt to round up support.

“I can get the eight votes,” he told Whitmire over the phone. Eight was the number needed to pass anything in the Houston city council. There was an embarrassed silence on the other end.

“Well,” the mayor finally said, “I’ve already made a decision this afternoon to go with a no-tax-increase budget.”

Greanias’ spirits sank. She had ignored him again. But this time, he thought to himself, it would be different. He would fight the mayor. And with that, the Great Houston Budget Fight was under way.

In these budget-conscious times the possibility that an elected official anywhere would try to raise taxes—much less take on a mayor to do so—seems like something that might happen only on a particularly cold day in hell. That is especially true of Houston. Houston’s municipal government has been ruled since practically the beginning of time by the ethic of low taxes–low services. Houstonians have long been loath to trust their civil servants with more than the minimum to keep city hall open.

But while boom times and the annexation of surrounding communities helped Houston grow and prosper, municipal services deteriorated. Over the years, the litany became all too familiar. Houston was known less for its graceful buildings than for its clogged freeways and sewer lines, the garbage and potholes that blighted its streets, its trigger-happy police force, and its abominable lack of parkland. And while the citizenry remained largely oblivious to the workings of its government, Texas’ largest city was being run like a corner grocery store. Budgets? They were proposed when the mayor got around to it—invariably months into the fiscal year. Need an outside lawyer or architect? No need to bother with competitive bidding; someone always had a buddy who could do the job. Promotions? They were a product of advancement on the actuarial tables rather than of merit. Houstonians weren’t paying much in taxes, but they were getting even less than they paid for. No wonder Houston got stuck with that awful, unshakeable label, the City That Doesn’t Work.

Much of the problem was that under the city charter, the mayor held all the power. The mayor could appoint and remove department heads, shift funds at will from one program to another, propose the budget, chair the city council and cast a vote within it, even create council committees and determine their membership. When the mayor wouldn’t clean up Houston’s problems, no one else wanted change badly enough to take the mayor on. Certainly not the chamber of commerce types; the businessmen who were city government in Dallas were content on the sidelines in Houston as long as taxes remained low and development unfettered. And not the city council members either; they were elected citywide, so they could blame poor neighborhood services on the bureaucracy and still get reelected.

In 1980 a change came to Houston that should have ended the mayor’s unchallenged rule: single-member districts. When individual sections of cities began to elect their own councilmen, their representatives started reflecting the diversity of urban Texas. Government by consensus was replaced by bitter debate; the new breed of councilman could afford to play the dissident as long as he kept his own constituents happy. Every big Texas city has had its examples: in Dallas, abrasive black advocate Elsie Faye Heggins and Lee Simpson, lawyer-spokesman for his district’s yuppie homeowners; in San Antonio, Bernardo Eureste, fanatically devoted to his Westside Hispanic constituency. And in Houston there was George Greanias, who decided during his second term to challenge Houston’s historic dedication to spending little and doing less.

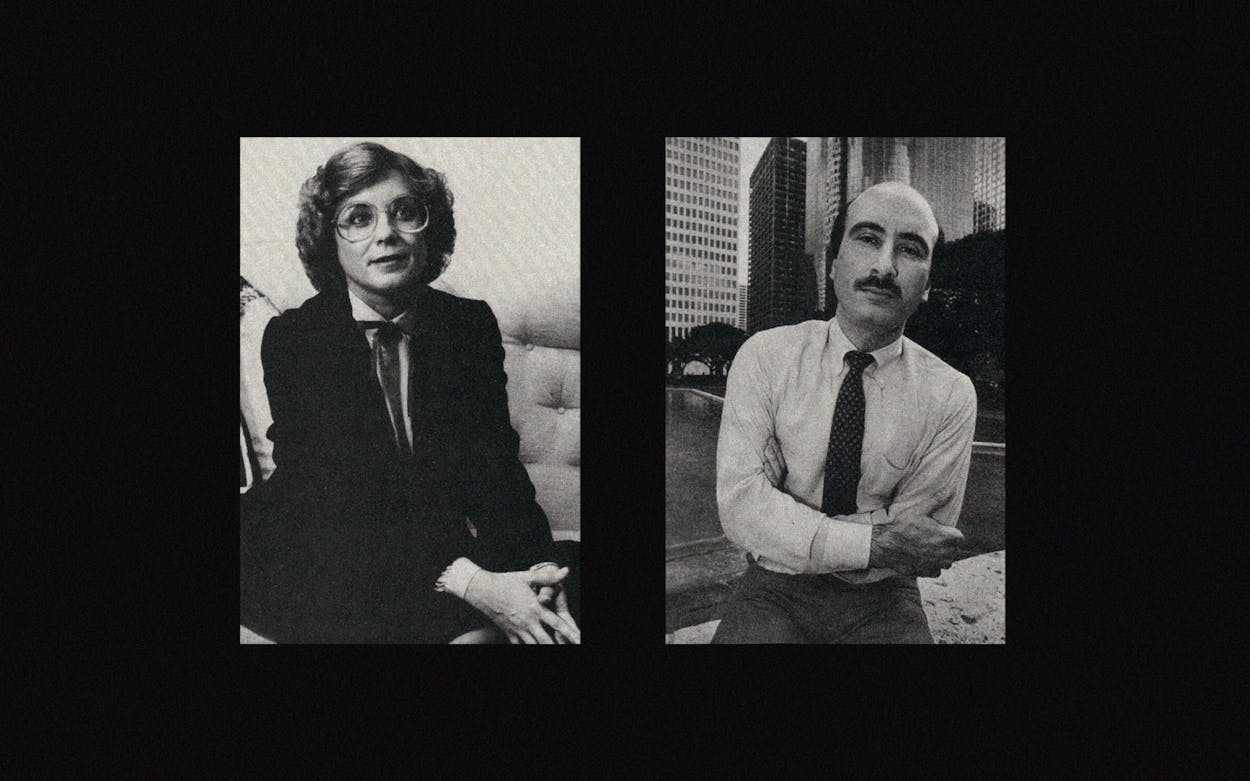

Greanias was the logical man for the job. He was short and slender; padding around his city hall office in his stocking feet, he looked a little like a bald Groucho Marx without the cigar. But at 36 he was bright, energetic, and articulate, a graduate of Harvard Law and Rice University, where he had returned to become an associate professor of administrative sciences. Like Whitmire, he was a good-government type, the sort who understood and cared about the minutiae of municipal government. Then, too, he was blessed with a constituency that would support his quest. Since 1982 Greanias had represented an eclectic but affluent district that included the Texas Medical Center, the Rice area, and heavily gay Montrose. It was a district that could afford and understand the need for a small tax increase.

Another reason the task fell to Greanias was that there was no one else. The Houston city council, to put it kindly, was not an impressive bunch. The primary claim to fame of Councilman Jim Westmoreland, for example, was that he had been taped in 1979 by undercover FBI agents in the Brilab investigation, boasting that he could steer them a city insurance contract. (No charges were ever brought.) One year later several other councilmen joined Westmoreland in voting to keep a new councilwoman from occupying an office next to theirs on city hall’s eighth floor. In 1983 the council voted to honor retired member Johnny Goyen by naming a bathroom in his honor.

For a while it seemed as though Houston would not need to rely on such a crowd to change city government. With the election of Kathy Whitmire in 1981, revolution would come from above. A serious-minded CPA and two-term city controller, Whitmire was elected on a promise to end the city’s bad old ways, and to a point, she delivered. She replaced the incompetent bureaucrats who had floated to the top of city departments with talented administrators. She stripped away civil service rules that had made waste an accepted part of the system. She civilianized police desk jobs to put more cops in the street, and her new police chief tamed the department. She applied competitive bidding to professional services. Her 1982–83 budget was the first one adopted on time in more than 25 years—an accomplishment she labeled the proudest of her first year as mayor. Through it all, George Greanias was her closest council ally.

But government inefficiency was only half the reason Houston wasn’t providing the services that are taken for granted in other cities. Lack of money was the other. In her third year in office, Whitmire was still talking about trimming waste and inefficiency as though she were an outsider looking in rather than a mayor very much in charge. Whitmire’s managerial bent caused her to focus as much or more on the process of government—getting budgets passed on time, naming good administrators—as on the result, namely improving the quality of life in the city.

Council members elected from single-member districts don’t have that luxury. The average Houston city councilman gets 17,000 calls and letters a year, most from people with complaints about what the city isn’t doing for them. Houston had not raised its property tax rate in ten years. The increase Greanias was pushing (5 cents per $100 of assessed property value) would have cost a family owning a $100,000 house only $30 a year, while providing $30 million to pay for new city services. Greanias and the mayor had much in common—they were both products of Houston’s newly acquired taste for better government—and many of their long-term goals were the same. But her method of gradually squeezing the bureaucracy until it yielded a bit more was simply too slow for Greanias and several like-minded colleagues. They split with the mayor because they had tired of waiting. In a practical sense, they needed better services, as did Houston. And they needed them right away.

Such battles are not merely matters of high-minded philosophical differences, of course. There were also the considerations of personalities and politics. Historically, the budget offered lower-level officials their best opportunity to prove they had the stuff for higher office. As controller, Whitmire had ridden the budget issue into the mayor’s office. Former councilman Lance Lalor had done the same to succeed Whitmire as controller. Though well-respected, Greanias fretted that he had been written off as a professional wimp, a nice-guy intellectual who lacked the nerve for the bruising fight. Taking on the mayor over the budget, he knew, would erase those doubts.

For her part, Whitmire worried about the effect a tax increase would have on her political future—she had promised no new taxes in her 1983 reelection campaign—and on the outcome of a $595 million bond election in the fall. But most of all Whitmire, fiscal conservative to the core, didn’t like the idea of raising taxes, whatever the need.

So it is no wonder that the battle lines were drawn as soon as Kathy Whitmire announced that the services the council members wanted had been left once again on the cutting room floor. What followed, ultimately, was a clash of visions. On one side stood the mayor, a halfhearted revolutionary determined to remain true to Houston’s tradition of low taxes–low services. On the other side stood a band of council members led by Greanias, convinced that it was time for Houston city government to do more, to start making up for the years of neglect. The fight over the budget would be in many ways a fight for Houston’s future.

“Kathy’s a Scrooge!” Council Charges

When Kathy Whitmire released her $1.2 billion budget on May 22, George Greanias stepped onto center stage. His task was formidable. Several of his colleagues also wanted the services that a tax increase would provide, but no one, including Greanias, would dare to propose one. Simply put, they were afraid. They knew well Whitmire’s vindictive side, her ready access to the press, and her quick way with a barb. They didn’t want to cross the mayor lest she brand them as big spenders, damaging their reelection chances in 1985.

Instead they hoped they could rope Whitmire into proposing a tax increase herself. Then they would gladly vote to raise taxes. “We’ve all said we’ll stand with her,” Councilman John Goodner told me, “but by God, we’re not going to stand against her.” As cochairman of the budget review committee, Greanias shrewdly redefined the debate. “The issue is not the tax level,” he insisted. “The issue is the level of services.” Not exactly Thomas Paine, but in Houston last May, those were fighting words.

Led by Greanias, the council launched its spring offensive. The budget review process, in which the council scrutinized the mayor’s funding for each department, gave the members a rare moment in the limelight, a chance for a crowd of Rodney Dangerfields to gain some revenge against a mayor who, they felt, had given them no respect. “We have no power whatsoever,” says Goodner. “The only thing we can do is vote and be noisy.”

So noisy they were. They gave Whitmire three months of excruciating budget hearings, dooming her hopes of passing the budget by July 1. The sessions became a public water torture for Whitmire, as witness after witness—her own department heads—delivered tragic soliloquies on their inability to carry out their duties with the paltry sums Whitmire had given them. The parks director begged for $900,000 more to staff new facilities; the public works department pleaded for money to tear down five thousand dangerous abandoned buildings and to pay the electric bills on 14,000 new street lights. The fire department lacked the men to staff new fire stations. And the council wanted money to clear weeds and trash from vacant lots and to clean drainage ditches to prevent flooding.

Even subordinates who subscribed to Whitmire’s blood-from-a-turnip money-saving techniques received no reward. Whitmire’s new solid waste chief, Charles Ware, had found that by shuffling work schedules he could provide heavy trash pickup (collection of tattered sofas and broken refrigerators left out on the street) without hiring extra men. All he needed was $6.5 million for equipment to get the program started. But Whitmire wouldn’t give it to him. Most of the new money was going instead to the police department, the mayor’s version of the Pentagon. Yes, Houston had come a long way under Kathy Whitmire. But as the hearings were making increasingly clear, the city still had a long way to go.

As the months dragged on, Greanias built a broader case against the mayor, directly challenging her fiscal competence. He argued that Whitmire had turned to gimmicks—reserve funds, onetime revenue sources, federal revenue-sharing and accounting maneuvers—to balance the budget, as required by state law. (The mayor later acknowledged employing some distasteful techniques to get through Houston’s hard times, but she persuasively disputed Greanias’ contention that she had acted irresponsibly.) And he warned of a day of reckoning. In 1985, Greanias asserted, those sources would be exhausted, and Houston would face a deficit of $40 million. “I see us digging ourselves deeper and deeper into a hole,” he declared bleakly.

In August the committee totaled up the changes it wanted the mayor to make and found—surprise, surprise—that they came to $30 million, precisely the amount in the tax-increase budget Whitmire had rejected. The council held out a faint hope that the mayor would take the blunt hint and propose her own tax increase. Its work done, the budget review committee sent its recommendations to the mayor on August 17, seven weeks after the start of the fiscal year, and awaited her response.

Whitmire was not amused. Speaking to reporters, she noted that the council members had failed to indicate how the city might pay for the extra programs they wanted. Greanias’ budget review panel, she wryly suggested, might be better known as the tax-increase committee.

Council Fiddles While Houston Burns!

Formally before the council for the first time on October 9—three months into the fiscal year—the Houston city budget made familiar reading. In response to the council’s advice, the mayor had added modest sums to correct mistakes and supplement a few underfunded programs, then sent it to the council for approval. There were no new programs. And of course, there was no proposal for a tax increase. The mayor had thumbed her nose at the council.

The council decided swiftly . . . to do nothing. Without any discussion of the budget’s content, four members invoked the tag rule. An example of the Houston city council at its most Byzantine, the tag rule allows a member to delay any new proposal for seven days. He may do so for strategic reasons—to give himself more time to round up votes, say —or merely on a whim. Later, any member who was absent the previous week may tag the proposal again, for another seven days. In theory the tag rule gives the council a lever of power, albeit puny. In practice, it can paralyze city government for weeks.

The budget vote would be delayed once more before reappearing on the agenda for Tuesday, October 23. But even before the budget was to come up, the council had another matter to consider. It was a budget amendment, introduced by eleven-term councilman Frank Octavius Mancuso, and the one spending proposal for which the council was willing to challenge the mayor. It was a direct slap at her—and a perfect example of why Houstonians have long been reluctant to entrust their city council with more money.

Earlier in the year Whitmire had stripped nine hundred police sergeants and lieutenants of their take-home cars, saving the city almost $6 million in 1985 alone. To compensate the officers, the council had approved Whitmire’s request to give them $2700 raises. Now Mancuso was arguing that the move violated an old council policy establishing parity in base pay between police officers and fire fighters. Long a flack for the city’s powerful fire union, Mancuso argued that the parity rule required the council to grant 661 fire department officers similar raises, at a cost of $1.6 million. The amendment was a blatant money grab by the union; the fire fighters, having lost no take-home cars, deserved nothing. Whitmire was particularly annoyed by Mancuso’s proposal to draw the money from the city’s rainy-day fund. Increasing that fund was one of her pet projects. Mancuso’s proposal passed, nonetheless, 11–4.

Finally the council was ready to debate its overdue budget. Almost. Now it was the mayor’s turn to drag her feet. Several members had been waffling, and the mayor’s floor leader, Anthony Hall, was unsure she had the votes to push it through. Unwilling to take chances, Hall won a 9–6 vote to delay another week. That was a mistake. According to Greanias, Whitmire that day had enough support to pass her budget and avoid the struggle to come. Instead, Hall’s proposal gave Greanias time to go to work.

Egghead vs. Tightwad: Battle Lines Drawn!

Greanias began by taking inventory. To get a budget with a tax increase, he would first have to find the votes to kill the mayor’s budget. There were fifteen votes on the council. Whitmire had five of them: her own, those of three of the four black council members (Hall, Ernest McGowen, and Judson Robinson, all Whitmire loyalists), and, from the conservative camp, that of Christin Hartung, who always jumped at the chance to decry a tax increase.

On his side Greanias knew he could count on Dale Gorczynski and John Goodner, both traditional Whitmire allies who were unhappy about city services. Greanias could also count on Eleanor Tinsley, who wanted a training class for fire department recruits and more paramedics. Councilman Jim Greenwood’s behavior was less predictable, but during the budget hearings he too had joined the chorus of complaints about city services.

That gave both sides five votes. Greanias turned his attention to the council’s old guard. Councilmen Westmoreland, Mancuso, and Larry McKaskle had no love for Whitmire, but they weren’t crazy about the egghead Rice professor either. Unlike most of their colleagues, they hadn’t participated in Greanias’ budget committee hearings. Greanias courted them anyway, playing on their antipathy for Whitmire. This was their chance to stick it to the mayor; she could be beaten on her own budget, he told them.

Still, Greanias was uncertain. That was when he turned to the old guard’s fourth member, Ben Reyes. The council’s lone Hispanic, Reyes hated Whitmire. He had endorsed her opponents in every mayoral race and voted against her on the council every chance he got. The feeling was mutual in the mayor’s office. Whitmire’s staff regarded Reyes as a shameless political hack willing to serve any special interest. Benny made deals—a scurrilous trait in Whitmire’s book. Normally, Reyes and Greanias sat on opposite sides of the fence. Now, through an intermediary, Greanias wooed him.

That left only Rodney Ellis. The lone freshman on the council, Ellis, 30, was a protege of liberal congressman Mickey Leland but had the smarts to cultivate establishment power brokers like 3DI chairman Jack Rains as well. Ellis was bright and sly; on the council he had played the humble rookie but was considered as good a bet as anyone to become Houston’s first black mayor. He usually voted with Whitmire, but he was also close to Greanias. On Tuesday, October 30, with the budget scheduled to come up at 2 p.m., Ellis was sitting squarely on the fence.

The mayor had been counting noses, too, and knew the vote was close. She called Ellis’ office at 1 p.m. to ask for his vote, but the councilman was at lunch. Ellis’ staff was frantically calling his usual lunchtime haunts when he sauntered back in ten minutes before the meeting and returned her call.

“What are you going to do?” Whitmire asked.

“I don’t know,” he told her.

“Well, I’m counting on you to be my eighth vote, so if you’re not going to vote for it, let me know,” she said.

Ellis mulled it over for a few minutes. The other black members were with Whitmire, but Ellis liked the idea of displaying some independence. He notified the mayor that he would vote against her.

Council to Mayor: “Drop Dead!”

At 2:20 p.m. Whitmire gaveled the meeting to order from her seat in the middle of the horseshoe-shaped council table. Despite Ellis’ decision, she had walked into the room thinking she might still have the votes to pass her budget. But as the council members walked in, she grilled them on their intentions and quickly realized she was coming up short.

The mayor turned to Plan B. Christin Hartung was absent from the meeting because her daughter had been hurt in an automobile accident in San Antonio. McGowen would be late. Under similar circumstances, the council had always accepted a request for a delay. Now Whitmire had arranged for Larry McKaskle, who was always deferential in matters of council etiquette, to make such a request.

“I understand that both council members Hartung and McGowen have requested that this item be postponed until they can be present,” Whitmire announced. Then she paused, waiting for McKaskle to respond to the cue. But McKaskle did nothing. Whitmire looked anxiously about the room for help, and finally Greenwood took the hint. But this time the delay was not going to be automatic. A roll-call vote was requested, and the motion for postponement went down, 8–5. Now Whitmire knew she was really in trouble. Hall, looking for any way to buy time, moved for a one-day delay. His motion failed, 9–4. Whitmire had waited for months for a vote on her budget; now, when she wanted a delay, the council was ready to move forward. The mayor had no choice but to open debate.

As television cameras rolled, George Greanias made his move. Services were suffering, he declared; increased efficiencies weren’t enough. “We haven’t been doing more with less,” he thundered. “We’ve been doing less with less.” and then he threw his rhetorical fastball. Standing in front of his charts and graphs, Greanias told the people of Houston that their mayor was setting them on a course of fiscal disaster. “If we approve this budget, . . . we have set a time bomb ticking,” he warned. “New York City did exactly the same thing.”

It was a strained comparison. Whatever its problems, Houston remains in basically sound shape, with a high bond rating; the city is far from the dire straits that brought New York near bankruptcy. But it made good copy—and inspired political strategy. Greanias had given the council members a fiscal-responsibility argument under which they could vote and hide. “That was critical to the success of the campaign to defeat the budget,” he told me later. “It allowed council members to reject it without being plastered as tax-increase advocates.”

Whitmire’s forces made a desperate bid to save the day. Councilman Robinson noted that a citizen had signed up to speak on the budget at the next day’s meeting. Another of the council’s nutty rules stipulated that any matter could be delayed for a day at a council member’s request if a citizen had signed up to speak on the issue at the next day’s public hearing. But this time Mancuso, the author of the rule, smelled a rat. When had the speaker signed up? He had telephoned, uh, ten minutes ago, came the answer. Interesting timing, noted Greanias, who pointed out that such requests must be made before the council meeting begins.

At last, one hour later, with McGowen returned to the chamber, the budget came to a vote: Whitmire yes, McKaskle no, McGowen, yes, then nine straight noes before Hall and Robinson’s futile votes in favor. Kathy Whitmire’s budget had gone down 10–4. George Greanias, once Whitmire’s closest ally, had assembled her most embarrassing defeat.

It had taken some old-style wheeling and dealing, but he had won. Now maybe the mayor would see the light. Maybe there would be a tax increase and some of the services Houston so desperately needed. Maybe things would really change.

Mayor: “Stop Playing Footsie With Benny!”

The day after George Greanias handed the mayor her lunch, he decided to be gracious; he knew compromise did not come easy to her. “Dear Kathy,” he wrote. “In spite of everything that happened, I hope we can work together on this issue.”

Not a chance. Greanias had impugned her fiscal expertise! She wasn’t about to let him get away with it. After conferring with her aides, she dismissed the idea of tearing into the councilman at a press conference and decided instead to be low-key about it. Whitmire’s experts would produce a detailed written response, full of charts and graphs, to rebut Greanias’ forecast of economic armageddon.

Then there was the question of what to do about the budget. The newspapers predicted a lengthy impasse unless the mayor decided to forgive and forget, an unlikely prospect. Whitmire, wiser in the ways of city hall, knew better. She realized that Greanias’ peculiar coalition was fragile, likely to fracture given a little time and a little pressure. She would remain firm and wait them out. And of course, she would not propose a tax increase. No, no, no.

Gorczynski was less reluctant than Greanias to gloat. “She basically said, ‘You’re not going to get anywhere with your objections because everyone will be afraid you’re in favor of a tax increase. I’m going to cram it down your throat.’ So you can imagine her surprise,” Gorczynski told me, laughing and slapping a lunchroom tabletop at the thought, “when she gets it thrown back at her. There’s a certain sense of satisfaction in it.” Gorczynski paused. “The grand question is, how do we get out of this?”

It was a good question. Greanias and the mayor had tied the council into knots. Untying them wouldn’t be easy, but Gorczynski was ready to act as peacemaker. After all, he had experience. In 1980 he had resolved a spat between McGowen and Goodner when one of McGowen’s volunteers, a male transvestite, had insisted on using the city hall ladies’ room.

Gorczynski arranged a 4 p.m. meeting on Monday, November 5, in Whitmire’s office. He and Kathy and George would hash things out. They would break this budget stalemate. They would do the right thing. For the people of Houston.

Greanias was wary but ready to make peace. He knew that the political ground under him might shift at any moment and that it was unwise to remain in the mayor’s doghouse. Things had come too far, too fast. Besides, the timing was right for a settlement.

At that same moment, Whitmire needed Greanias’ help on a completely different matter. She had nominated Seattle fire chief Robert Swartout to run the Houston department and had submitted his name for council approval. No problem—in most cities. But Houston’s fire union had been so powerful for so long that there was still on the books a 1941 ordinance requiring that the fire chief be appointed from within the department. It was precisely the sort of thing that good-government types like Whitmire and Greanias had sworn to oppose. Whitmire had placed the odious ordinance’s repeal and Swartout’s confirmation on Wednesday’s council agenda. The fire union was lobbying against her, and the vote looked close. Before their falling out, Greanias had encouraged Whitmire to hire Swartout and had pledged his vote. But now he was backing off. He’d even hinted that he might support Reyes in his bid to block Swartout’s appointment.

But first things first. The meeting Gorczynski had arranged was to talk about the budget. Greanias and Whitmire talked amicably until the councilman began telling the mayor all the high-minded reasons why ten members had voted against her budget.

“There are other reasons why the budget failed,” Whitmire interjected, not in the mood for a lecture.

Oh?

“You’ve been playing footsie with Benny!” Whitmire declared.

Sin of sins! She was accusing Greanias of cutting a deal with her bitter enemy, of agreeing to vote against the fire chief in exchange for Reyes’ vote against the budget. Infuriated by her attack on his integrity, Greanias stormed out of Whitmire’s office. The mayor and Gorczynski were left staring at one another.

After a few minutes Whitmire picked up the phone and called Rodney Ellis’ office for help. “I’m trying to make peace with George,” she told Ellis, “but I’m not doing very well.” Whitmire and Gorczynski went upstairs to meet Ellis, took him with them to find Greanias in his office, and resumed their talks.

Greanias was willing to bury the hatchet, but he had a price. Using his hold over the budget and his fire chief vote as leverage, he offered Whitmire a proposition. Greanias would later call it a compromise; the mayor would denounce it as a deal. It was to work like this: Greanias would vote to repeal the ordinance and approve Swartout, and—giving up his tax-increase fight for another year—round up the votes to pass the budget. In exchange, Whitmire would establish two new committees and appoint Greanias to them. The first would study the use of Houston’s civic center buildings, which had been running in the red. The second, the one that became the focus of the bargaining, would give Greanias what he really wanted: some council influence over how the city was run. It would be a finance and management committee, working closely with the finance department in preparing budgets and monitoring city departments.

The mayor balked. He wanted her to appoint a committee to share her power? Not likely.

At eight they moved to a restaurant at the Hyatt Hotel for dinner. Gorczynski left, but three Whitmire aides took his place. Whitmire now offered, instead of Greanias’ committee, an ad hoc group with the more modest charge of studying Houston’s use of bond money and federal revenue sharing. Now it was Greanias’ turn to shake his head. That was not enough. The meeting ended well into the evening. Nothing had been resolved.

“I’m Not a Wimp Anymore!” Says George

George Greanias was wrestling with his conscience. He knew the ordinance barring Houston from hiring an outside fire chief was silly, one of the excesses that the city’s unions had employed to handcuff city hall. But the mayor wanted his vote, wanted it desperately, and it was the only leverage he had to get a tax increase that would clean up Houston’s streets. “I’m being stubborn,” he told me. “The mayor’s being stubborn on the budget. I’m holding out.” Moreover, Greanias had a point to make to the mayor. “Right now Whitmire has no faith that I’ll carry out a threat,” he said. “She thinks she can get around anybody in council.”

Greanias was still squirming Wednesday, November 7, when the time came to head downstairs for the council session. This was his first experience at playing political hardball. “Losing your political innocence is a painful process,” he said with a heavy sigh. As it turned out, he would lose nothing that day; Ben Reyes tagged the fire chief vote for another week. During the meeting, Greanias spoke privately with Whitmire about his ideas for a council committee to help manage the city. “You’re not mayor yet, George,” Whitmire snapped. “I’m the policymaker. Keep your nose out of it.”

When the fire department ordinance came up the following Wednesday, November 14, Greanias went through with his plan to vote against its repeal. It was lifted anyway, by an 8–7 vote. Then Greanias switched sides and voted to confirm Swartout’s nomination.

For Whitmire, it wasn’t enough. During a break in the meeting, she ratted on Greanias to the press. The councilman had offered to vote to repeal the ordinance in exchange for two committee chairmanships, she told reporters. She had rejected the offer, of course. “I felt that everyone had to vote on the merits of the issues and not on the basis of other considerations,” she said sanctimoniously. It was classic Whitmire, the politician with the pointed disdain for politics. Later Greanias bristled at her holier-than-thou attitude. “The idea that she never wheels and deals, that she’s above all that, is bull,” he told me. He remembered a deal that she had offered him on the previous year’s budget: if he would push it through, she would authorize a consultant’s study of city user fees he wanted.

By now the philosophical debate about how best to improve the level of services had degenerated into a brawl. Egos were on the line, and the original point of the exercise had been all but forgotten. Whitmire believed that several council members had voted against her budget simply because they were angry that she had nominated Swartout. With that vote behind her, she was beginning to smell victory on the budget. She took the offensive. Council members began to receive calls from Houston heavyweights like developer Kenneth Schnitzer, Walter Mischer operative Jim Edmonds, and Jack Rains, who urged them to pass the budget immediately to avoid holding up city bond sales. In fact that danger didn’t exist; the city wasn’t planning to hold a bond sale for months. The members’ phones started ringing after Clarence West, Whitmire’s chief council lobbyist, had called business leaders on the mayor’s behalf.

On Monday, November 19, the mayor released a 27-page response to Greanias’ forecast of fiscal doom, including 16 pages of charts and tables buttressing her argument that the city budget was as sound as the dollar. She continued one-on-one meetings with council members; she leaned on them to vote for her budget even though she had offered no concessions. And on the day before Thanksgiving, the mayor’s office produced an agenda sending her budget to the city council for the third time. It was almost exactly the same document the council had rejected less than a month before.

Oh, That Kathy! Council Whitmired Again

Greanias spent Thanksgiving at home with his mother and grandmother. Whitmire tried to call him over the weekend but had been unable to get through, Greanias later explained, because his phone had shorted out. In frustration, on Sunday she called Rodney Ellis, who suggested that the three of them have dinner the next evening.

They met at 8:45 at the River Cafe, a swank restaurant in Greanias’ district, and talked over lamb chops and red fennel sausage. Whitmire had wanted the meeting, and Greanias wondered what she had in mind. “Why are we here?” he asked. “To figure out how to pass the tax rate,” said Whitmire. The mayor was taking a new tack. She was never going to raise property taxes, she told him, and the council obviously wasn’t going to do it over her objections. Still, the council had to establish an official tax rate, even if it was unchanged. And it had to do so quickly so tax bills could go out and Houstonians could pay them by year’s end. They needed to do it that Tuesday, Whitmire said, before six members of the council left on a junket to Taiwan.

Greanias knew Whitmire was right; his dream of a tax increase in the 1985 budget would remain just that. He and Ellis agreed to vote to keep the tax rate at its current level. But Greanias wanted something from the mayor in return. Earlier she had agreed informally to a suggestion by Gorczynski that any windfall in city revenues go toward the services at the top of the council’s shopping list. Now Greanias wanted a formal commitment, a budget amendment that would place any unexpected property tax revenues in a special fund. As money became available, it would fund, in order, heavy trash pickup, demolition of abandoned buildings, trash removal and weed-cutting on vacant property, and the cleaning of drainage ditches and culverts to prevent flooding. Whitmire accepted the deal.

All that was well and good, but it didn’t resolve the budget impasse. Greanias had one more trick up his sleeve. Because the budget was months late, Greanias knew that city departments would spend far less than the budget gave them, which meant there would be a tidy surplus by mid-1985. Whitmire had made a habit of rolling that money over for the next fiscal year, using it for programs she wanted. But Greanias had other ideas. He would propose a budget amendment that would force the mayor to spend that money on the services the council wanted. It would take some lobbying to collect the votes to push the idea through the council, and Greanias wanted to make sure he’d have the time. He knew Frank Mancuso wanted to delay the budget for two weeks until the council members returned from Taiwan, and he mentioned that to Whitmire. When she offered no objection to the delay, Greanias felt safe. There was no need to rush. He could devote the next morning to rounding up votes for the deal he had reached with the mayor and then have another two weeks to lobby for his new secret budget plan.

When budget discussion began, at about four-thirty on Tuesday, Greanias urged the council to approve the tax rate. With his backing, it would pass easily. Then he proposed the plan he had worked out with the mayor to use any tax windfall on city services. That motion passed. Then, since Mancuso’s first police-fire parity amendment had been wiped out with the defeat of the budget, the councilman introduced it again. It too was approved.

As the meeting droned on, Whitmire eased out of her seat to talk to Mancuso. George had gotten his amendment, and you’ve gotten yours, she told him. Why postpone the budget for two weeks? “I wanted to make sure you weren’t going to try to pass it while we were in China,” said Mancuso, ever the wary pol.

“We’d never do that,” said Whitmire coyly. “But if it passed today, there wouldn’t be any way that could happen.” Mancuso thought for a bit and seemed to like the idea. When Greanias looked to Frank Mancuso to propose a two-week delay in the budget, Mancuso sat mute.

Like Whitmire on the day her budget had been defeated, George Greanias was caught off guard. He had done as she had asked—supported the tax rate—and now Whitmire was stabbing him in the back! He offered his own motion for a two-week postponement. But now his colleagues on the council had had enough. “I’ve supported Councilman Greanias throughout all of this,” said Greenwood. “We’ve hassled with it for quite some time. I would like to see us get on with it.” Greanias’ motion to postpone failed 7–6.

Finally, on November 27, six months after the budget had been proposed and five months after it was supposed to take effect, the Houston city council was ready to vote again. The budget was basically the same document the members had rejected 10–4 just one month ago. But this time they approved it 11–2, with Greanias and Reyes, the unlikely bedfellows, the lonely votes against.

Kathy Whitmire had pulled off an impressive feat. Once again she had worn them down. She had won. But won what? She had shown the council who was boss, no question about it. But there would be little improvement in city services for at least another year. And her victory was bound to produce a bitterness among her former allies that would linger far longer.

After the vote, Greanias headed for the elevators, his suit coat slung over his shoulder in defeat. Mike Loftin, Whitmire’s budget director, rushed over to try to make amends. Greanias glared at him.

“I carried your water on the tax rate deal, and she turned on me. Real shabby,” he said, shaking his head. Then George Greanias, bruised but wiser, looked up and smiled the thinnest of grins. “Well,” he said, “next year.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston