Before Blackhawk helicopters circled overhead or Secret Service sharpshooters lurked in the switchgrass or Saudi princes breezed down Main Street, Crawford was an ordinary small town, its only landmark an old cottonwood tree that stood next to the blinking red stoplight. Cottonwoods rarely grow far from rivers or creeks, but this one had sprung, improbably, beside the cracked blacktop, in a ditch where rainwater pooled after storms. It was a stately, wide-limbed tree, used by locals for giving directions and approximating distances, as if it were the axis on which the town revolved. Ranchers used to trade cattle under its splayed branches, and children—now grandparents—had climbed up its furrowed trunk. The tree had endured hail, tornadoes, and months without rain, and lightning had spared it more than once, skittering past it down the telephone wires. But it could not endure the changes coming to Crawford. Early one morning in August, without warning or explanation, the tree was cut down and hauled away.

Anyone wondering why only had to look a few feet beyond the tree’s severed trunk to the Yellow Rose, the eighth gift shop to open on Main Street since Crawford’s most famous resident, George W. Bush, became the forty-third president of the United States. Before it was felled that day, the tree had obscured the view from the street of the Yellow Rose. Now the gaudy storefront—a scaled-down reproduction of the Alamo—dominates the center of Crawford. Kids rode their bikes down Main Street to stare at the spot where the tree had stood; one woman salvaged part of its trunk, which lay across the sidewalk, and carried it home. All afternoon the tree was discussed under the bubble dryers at the Great Shapes beauty shop, over cups of coffee at the Fina, and around city hall. The rumor around Crawford was that the Yellow Rose’s owner, an out-of-towner named Bill Johnson, had cut down the tree himself, although the truth was more complicated. The actual culprit was the Texas Department of Transportation; the tree had been not on Johnson’s property but on the state’s right-of-way. “I told them that the tree was theirs and if a branch so much as scratched this place, it was their problem,” Johnson told me. “I said, ‘You’re on notice. I spent a lot of money over here.'” Then he shrugged. “That thing was half-dead anyway.”

Crawford’s 705 citizens had been unfailingly polite as the slow rhythm of life was disrupted by a cavalcade of reporters, hucksters, protesters, curiosity-seekers, tourists, and Secret Service agents, but the reaction to the tree’s razing was swift and decisive. That night, someone—no one will say who—hurled a rock at the Yellow Rose, smashing its front window. Police chief Donnie Tidmore’s investigation has so far turned up no leads. “A few people came up to me afterward,” Tidmore recalled from his one-room station house on Main Street, with an expression of barely contained amusement. “They said, ‘Chief, I want you to know I didn’t break that window, but that’s only because someone beat me to it.'”

Crawford lies eighteen miles west of Waco, on a stretch of the Santa Fe railroad line that runs north along the Blackland Prairie. The town is little more than a wide place in the road—a place that evoked, until recently, the same desolation as the town of Thalia in The Last Picture Show. A handful of mom-and-pop stores lines one side of the two-block span of Main Street, which runs parallel to the railroad tracks, past grain silos and a new billboard that says, “Welcome to Crawford, Home of President George W. Bush.” I first drove into town at the start of the president’s “working vacation” in August, when the town was overrun with grasshoppers, which stuck to tire wheels and crunched under boot heels and gnawed their way through acres of Central Texas farmland. Which scourge residents dreaded more—crop-devouring insects or the swarming White House press corps—was debatable. Inside the Crawford Elementary School gym, which the White House had transformed into a press briefing room, school officials installed a steel barricade to keep reporters at bay, allaying one parent’s concern that journalists might be as predatory of children as they were of breaking news stories. Reporters intent on catching a glimpse of the president had to spend their days here, as I did for most of August, killing time while awaiting the hoped-for-but-infrequent announcements from the White House Press Office that President Bush had decided to grant us an audience.

Long gone are the more casual days of political reporting, when Lyndon Johnson used to barrel around his ranch in his Lincoln convertible, entertaining reporters with stories of the ribald ways of bulls. The scrutiny of the 24-hour news cycle, in which one misstep can spell disaster, makes it impossible for a president to be so spontaneous or collegial, even if Bush were so inclined, which he is not. He values his privacy more than recent presidents have, and he harbors a dislike for the media that dates back to his encounters with them during his father’s 1988 presidential campaign. The Bush ranch, which is eight miles from town, is strictly off-limits to the press unless the president extends a rare invitation there. Reporters usually see him only when he leaves the ranch, and in a carefully stage-managed setting. When Bush visited the Coffee Station on Main Street last New Year’s Eve, the cafe’s diners served as a backdrop of “real” Americana, despite the TV cameras trained on them, the gawkers peering in, and the watchful stares of Secret Service agents, who had previously searched them outside with magnetometers in the 39-degree chill. Bush, wearing blue jeans, took time to shake hands and field questions from reporters. His visit was a chance to connect with fellow Texans and the media, but it was, above all, a photo op: a portrait for the press of the president as a regular, down-to-earth guy. “Order me a cheeseburger,” Bush had said as he strode inside. “I’m going to walk around and meet the people.”

Journalists in Crawford who wanted to see the George W. Bush they had known on the campaign trail—a guy who was loose, funny, and eminently available—were out of luck this August. The White House Press Office had little reason to give us access to the president, who was enjoying a 68 percent approval rating. And so with no alternative, we waited in the gym for news of the president’s whereabouts. And waited. So pronounced did his absence in Crawford become, even by the standards of a working vacation, that the New York Times wryly noted, “As the summer has drawn to a close, Mr. Bush has nurtured silences that even Calvin Coolidge would envy.” But as was true in Washington when there was no news, reporters still had daily newspaper columns and airtime to fill. Fox News’s Brian Wilson explained his predicament to me one day in the gym: “By next Monday, I will have covered the president for a week in Crawford, and I will have traveled with him across the country to California, Oregon, and New Mexico, reporting on him ad nauseam, and I will most likely never have laid eyes on him.”

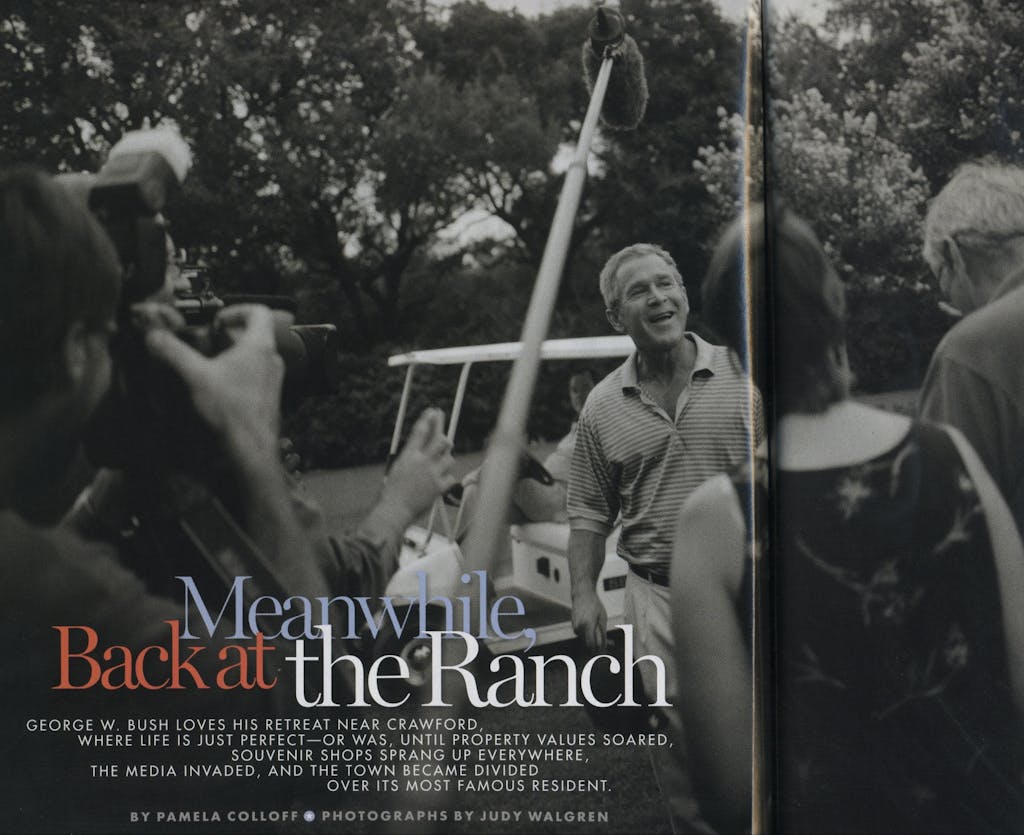

So I felt lucky when, early on during my time in Crawford, I was one of a dozen or so reporters the White House Press Office picked to be in “the pool,” the group that would cover the president’s first trip off the ranch. The occasion was an early-morning round of golf at the Ridgewood Country Club in Waco. To the uninitiated, life inside “the bubble,” the perimeter that the Secret Service establishes around the president, can be surreal. Pool reporters ride at the back of the motorcade—a procession of fifteen vehicles, mostly black Suburbans, led by two state troopers’ cruisers, tailed by an ambulance, and watched over by a helicopter. As the sun rose that morning, the convoy wove its way through the prairie grass, past grazing cows and pastures thick with wildflowers, down two-lane country roads toward Waco. Half an hour later, the motorcade pulled into the country club’s driveway, at which time photographers began running toward the clubhouse, craning for a view of the president.

Tanned and relaxed, he was sauntering ahead of us toward his golf cart in a lavender-striped polo shirt and white pants. He turned and squinted at us, grinning, seeming quite amused by the press stampede, which several Secret Service agents halted thirty or so feet from him. “Stretch!” Bush called out across the lawn to the tall Bloomberg News scribe, Richard Keil, whose pug had had a near-death encounter with a car that week. “I’m sorry about your dog.”

“Thank you, Mr. President!” Keil shouted back.

Bush practiced his swing and teed off, with a long drive that veered a bit too far to the right, then he approached the press gaggle to answer questions. The presidency has aged him tremendously; his hair has turned a patrician silver, and his forehead is deeply lined, so much so that the hard contours of his father’s face are becoming his own. Standing before the TV cameras, Bush answered questions with a blunt efficiency. He expressed his optimism about the flagging economy, artfully dodged a question about Americans’ preparedness for casualties in a war with Iraq, and held forth on Saddam Hussein: “The consultation process is a positive part of really allowing people to fully understand our deep concerns about this man, his regime, and his desires to have weapons of mass destruction. Last question—and then I’ve got to go chip and putt for a birdie.” He departed down the fairway, and Secret Service agents herded us back to the clubhouse, where we were required to stay, under their watch, for the duration of the round, until Bush reached the eighteenth hole two and a half hours later. After taking six strokes on the par-four hole, he conceded it to former state senator David Sibley. Bush declined to tell us his score. “I had a lot of fun,” he said cheerfully. “It’s good to be back here with my friends in Texas.” He shook hands with onlookers outside the clubhouse, hopped in the waiting motorcade, and then he was gone.

Whenever the president steps into his black Suburban, the motorcade starts to move, and it will roll along at a rapid clip whether reporters are in their vehicles yet or not. We were standing about thirty feet away when it took off. And so we began a mad dash across the manicured grass to our already-moving van, into which we leaped and collapsed, panting, with elbows and camera lenses stuck every which way. (“I once got left behind at the Great Wall of China,” CNN cameraman Barry Schlegel later told me.) But for all the oddity of the situation, and for all the staginess and canned sincerity that makes it easy to be cynical about modern politics, watching the expressions of people standing by the side of the road when the presidential motorcade returned to Crawford was very moving. Here, at last, was a genuine political moment. Waving families stood on their porches, cheering. Kids ran alongside the motorcade with tiny American flags. Farmers stood in their pastures and took off their hats, nodding in deference. An older woman who was bent over her flower bed stood up, startled, and beamed. Along Main Street, people gaped and smiled and stared in wonder. After all, somewhere in that procession of black cars that careened past them, somewhere behind those dark tinted windows, was the president of the United States.

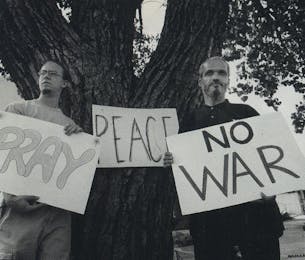

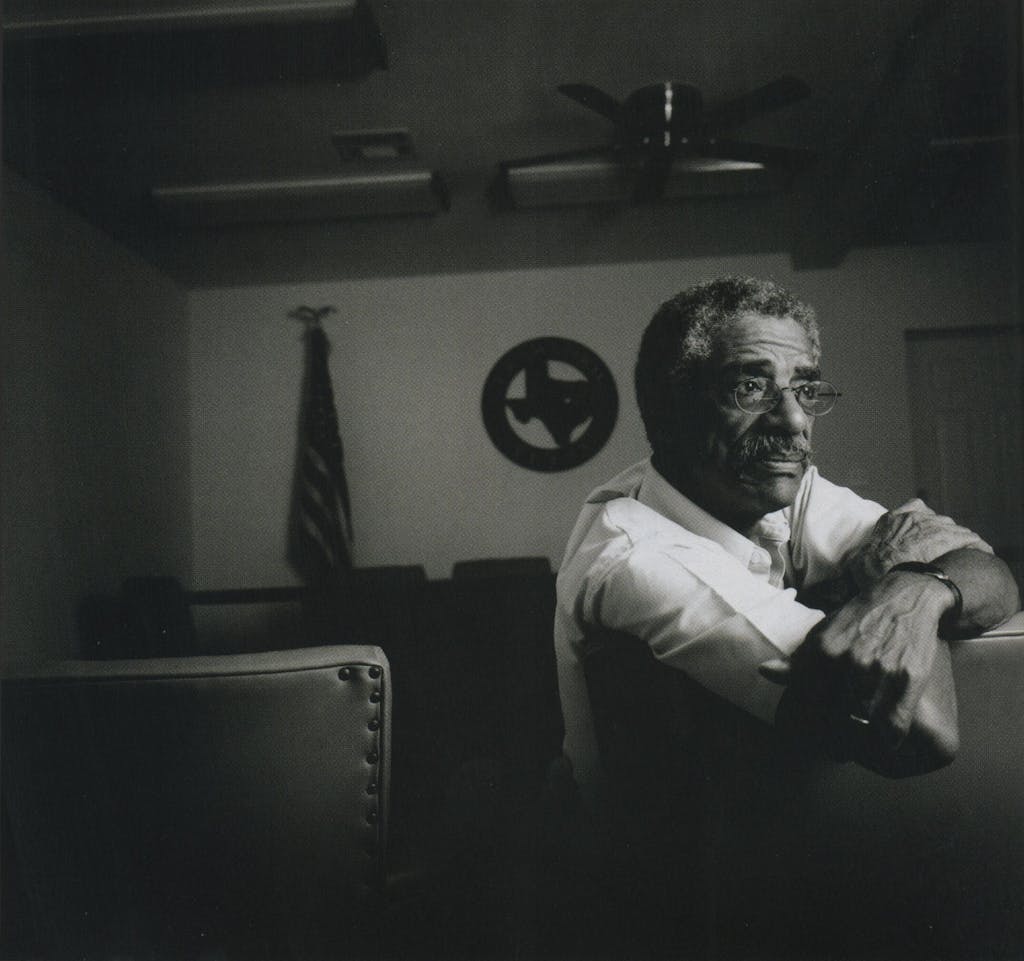

The second most famous politician in town is Robert Campbell—an unapologetic Democrat and the mayor of Crawford. (“It’s just so embarrassing,” one local Republican whispered.) When Campbell is not checking the town’s water meters or worrying about its leaky sewers, he is the minister of the Perry Chapel United Methodist Church, a modest white clapboard building that sits at the heart of Crawford’s tiny black community, east of the railroad tracks. Campbell is a tall, sinewy man of sixty who wears bifocals and a perpetually worried expression, which will give way without warning to an easy, boisterous laugh. I first met him one Sunday when I went to Perry Chapel to see him preach. Inside the sanctuary, decorated with a simple cross of two unvarnished cedar branches, Campbell addressed the congregation, mostly older women in wide-brimmed hats and vivid silk dresses. When a nearby train sounded its horn, he raised his voice above it, preaching from the Book of Isaiah and its lesson of beating swords into plowshares. Campbell is a contained, unassuming man until he is behind the pulpit, and then his voice thunders with conviction. Gripping the lectern that Sunday morning, he urged his parishioners: “Let’s pray that God will lean on our world leaders so that they will give us what we want: Peace.”

Mayor Campbell says he is “neutral” about having the president for a neighbor, but his lukewarm embrace of Bush has divided the town as much as the changes taking place all around. “My job is to look out for what’s best for Crawford,” he explained. “It’s not about party affiliations. This town has limited manpower and limited resources, and the president’s presence here has put an enormous strain on us.” As proof, the mayor points to the demands on the town’s two-man police force, the wear and tear on its roads, and inflated property taxes, which have soared in the past two years along with property values. Tourist dollars, Campbell said, have been poor remuneration; sales tax revenue makes up just 7 percent of the town’s annual budget. What the mayor does not articulate, but which is at times evident, is his more personal ambivalence about the president. Campbell grew up in the projects of North Philadelphia, and the subjects of hunger and poverty are recurrent themes in his sermons. “People who get out of the projects always remember where they came from,” he said. So what does he think of a president whose life experience is so fundamentally different from his own? Out of political necessity, the mayor is discreet. When pressed, he said, “We see the world differently. The children of politicians won’t be the ones fighting a war in Iraq.”

Mayor Campbell’s job does not hinge on heady geopolitical conflicts but on crises as varied as missing manhole covers and stray dogs. The mayor had to interrupt our first conversation when a water main sprang a leak; only he knew exactly where the pipe ran beneath the asphalt—because he had long ago laid it himself. Few politicians know their territory as intimately as Campbell, whose nuts-and-bolts knowledge of the town has been gained the hard way. After retiring from the Air Force in 1982 and marrying a local woman, he took the only job offer he got: to be the Crawford maintenance man. For three years he patched the town’s streets, fixed its water and sewer lines, cut its grass, and ran a bulldozer to its dump. When he went to college on the GI Bill and then to graduate school (he earned bachelor’s degrees in business administration and social work at Baylor University and a master’s in divinity at Southern Methodist University), he worked part-time as the town mailman, learning the names of future constituents along his route. He served for nine years on the city council and became mayor in 1999, when he won accolades getting the town on sound economic footing. But when George W. Bush was elected president, the mayor’s constituency split along political lines. Two years ago Campbell’s run for mayor was uncontested, but this May he barely prevailed against a Republican by a margin of six votes.

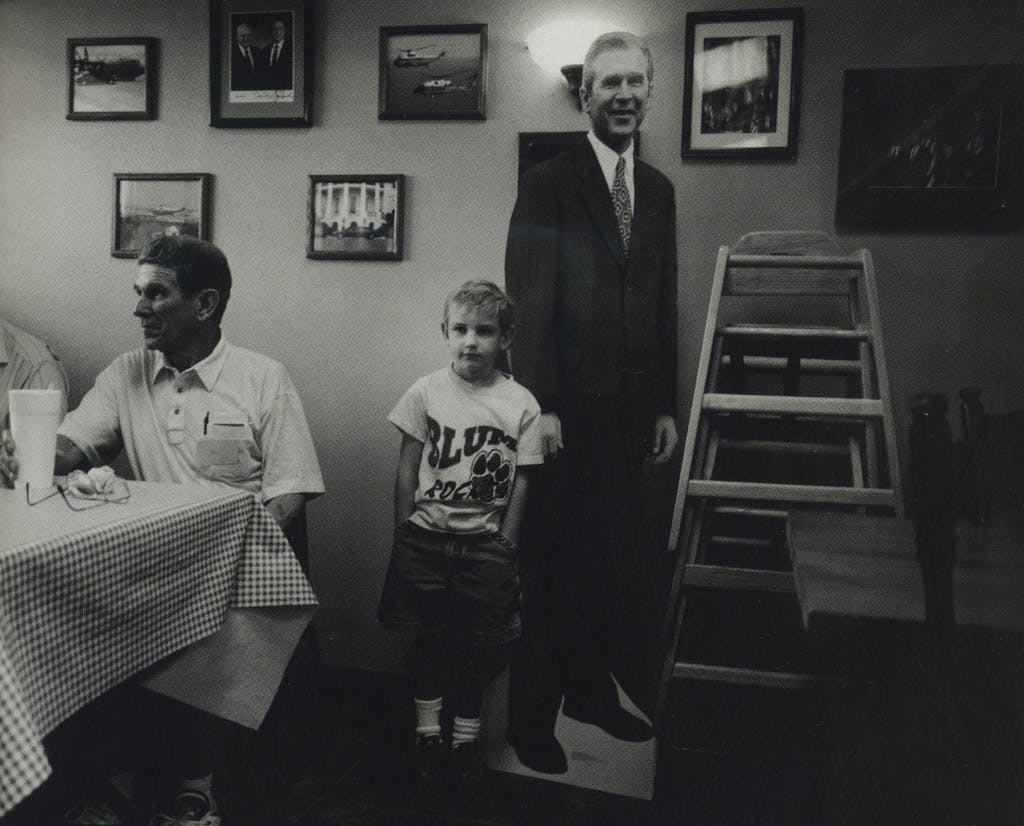

From his vantage point at city hall, on Main Street, Mayor Campbell can do little but watch as the topography of his town becomes increasingly unfamiliar. Across the street, the American Legion Hall and the old feedstore have been demolished to make room for a bank—built in anticipation of Crawford, with its top-notch schools and new cachet as home of the president, soon becoming a bedroom community of Waco. North of town, in the brand-new River Oaks subdivision, where homes cost up to $1 million, emerald green lawns meet the prairie grass. On Main Street, a steady trickle of tourists peers in the windows of the new gift shops stocked with souvenirs: “This Is Bush Country” refrigerator magnets, “A Merry Christmas From Crawford, Y’all” tree ornaments, rhinestone “Dubya” pins, White House snow globes, “Go Get ’em, George” coasters, and “Western White House” koozies, to name a few. One block south on Main Street, inside the Coffee Station, tourists pose for pictures next to a life-size President Bush cardboard cutout and scrawl greetings in the cafe’s guest book. (A recent sample: “Love you, W!” “God bless our prez,” “Great to be in Bush country,” and most pointedly, “Where’s George?”) “We need billboards on I-35 directing people to Crawford,” says Valerie Duty, a Waco resident who sells souvenirs at Crawford Country Style. “We can be a destination point, like Fredericksburg.”

Mayor Campbell takes off his glasses and wearily rubs his eyes when I ask him about his critics, who accuse him of failing to capitalize on the town’s newfound fame. “Let me explain,” Campbell said. “I am not trying to be isolationist. I’ve asked that the Bush Presidential Library be built at Baylor. That would be beneficial to us in the long-term. But we also need to plan in case President Bush sells the ranch. He has no roots here. And what then?” He worries that Crawford will be left in the lurch after the Bush presidency is over. “We need a grocery store, not a ninth souvenir shop,” he said. But two of Campbell’s parishioners, the Hemphill sisters, take a more philosophical view. Margie, 81, and Vickie, 82, have seen Crawford through its booms and busts, all while cleaning white people’s houses and caring for their sick on the other side of the tracks. I talked to them one day after church in Margie’s living room, where the sisters sat on a faded yellow flower-print sofa that had belonged to B. F. Engelbrecht, Margie’s former employer and the man who sold his ranch to Bush in 1999. As governor, Bush slept on the sofa once when he visited the ranch, and the Engelbrechts later gave it to Margie as a keepsake. She smoothed it with her hand as we talked about the ways Crawford was changing. “We live next to the railroad tracks, and we’ve gotten used to the trains passing by,” Margie said with a shrug. “We’ll get used to this too.”

Margie had only one complaint about the president, which she waited to mention until I had stood up to leave. It was a fact that Mayor Campbell had no doubt dwelled on, privately. “Mr. Bush has gone to other churches in town. Why hasn’t he come to the mayor’s church?” she asked. Then she patted the worn couch, as if she had said too much. “He’s always welcome to come pray with us.”

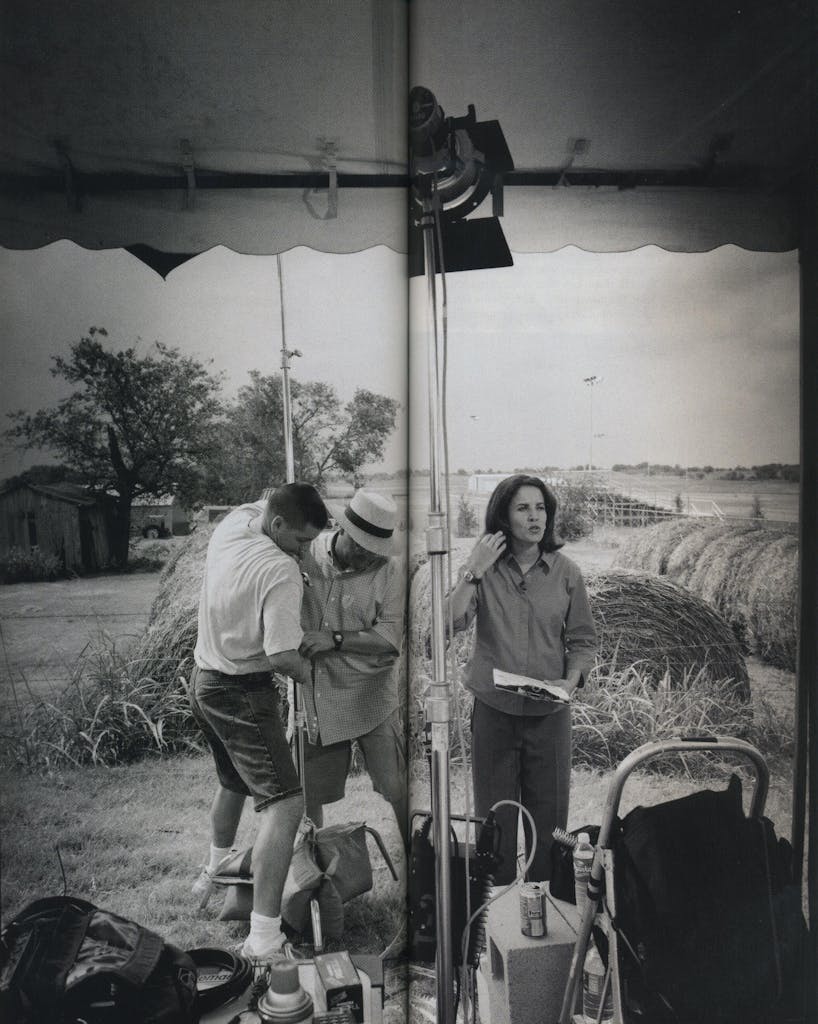

Back at the Crawford Elementary School gym, five blocks away, reporters sat and waited for something newsworthy to happen. Every few hours, TV correspondents would walk outside into the blistering heat to shoot a news segment—a ritual that involved the frantic powdering of noses, the rehearsing of lines (“No decisions on military action have been made . . .”), and the application of so much hairspray that the wind blowing in off the prairie could not rustle even one strand of hair. If you have seen a news clip from Crawford , you are familiar with the backdrop: Behind the reporter lies an idyllic green pasture dotted with hay bales. This is not, in fact, the Bush ranch, as most TV viewers might assume. Reporters are actually in town, standing in a parking lot, next to a field and the Crawford High School running track.

Inside the gym, fifty or so newspeople—print reporters, TV and radio correspondents, photographers, producers, sound techs—sat at long folding tables, where they typed on laptops and waited, and waited, and waited some more. It was a grim assignment for some of journalism’s brightest stars, who were reduced to groveling before White House Press Office underlings, recent college graduates who lorded their power over us like imperious waiters. A vast navy blue curtain separated us from the press office, whose staffers rarely ventured beyond it, since reporters (myself included) tended to corner them with nervous inquiries about our chances of seeing the president on the ranch. Each day, we waited for the blue curtain to stir, bringing news that the president had cabin fever and wanted an audience. Each day we were disappointed. “Did you hear?” a reporter cracked. “There’s an Amber Alert out for the president!” And so, day in and day out, we idled away the hours reading each other’s stories. “The only glamorous thing about being a White House correspondent is getting to tell your friends that you’re a White House correspondent,” groused one White House correspondent.

The tedium of our days was interrupted when the press corps discovered, with much carping, that President Bush had invited one reporter—Scott Lindlaw, of the Associated Press—to the ranch while leaving the rest of us behind. Not long after Lindlaw’s article appeared on the AP wire, one annoyed reporter posted a sign in the gym: “Spend a day with the Rancher-in-Chief! Sign up for your chance to report first-hand on how the President spends his vacation at Prairie Chapel Ranch. *Help him clear brush and burn cedar. *See if you can reduce your heart rate to 44 beats-per-minute after a three-mile run across the prairie. *Bring the First Lady her morning coffee. ‘I had a great day,’ says AP’s Scott Lindlaw. Sign up now!”—below which several reporters had dutifully written their names. Not long afterward, White House spokesman Ari Fleischer arrived in Crawford to hold daily press briefings in the gym. Invariably, these briefings began with a remark about how President Bush had been working up a sweat clearing brush back at the ranch. So ubiquitous did the term “clearing brush” become that the Washington Post published an in-depth article on the subject. (“Brush-clearing is can-do, hands-on, results-oriented—all the things a chief executive strives to be.”) We never actually saw the president clear brush ourselves; instead, the press office issued official photos of him in a sweat-stained T-shirt and a white Stetson, gritting his teeth as he carried a load of freshly cut cedar over his shoulder.

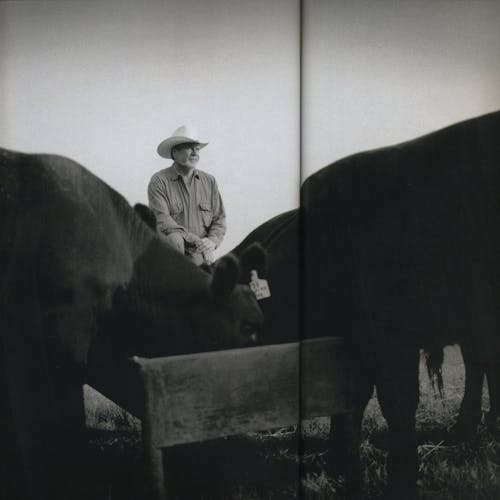

The White House Press Office understands that symbolism is at least as important as substance when the president is home on the range. Bush knows this as well—that the ranch, which he seems to genuinely love, is as much a political tool as a retreat. “Most Americans don’t sit in Martha’s Vineyard swilling white wine,” Bush told the Associated Press this summer in a jab at Bill Clinton. (Most Americans don’t own a 1,583-acre ranch either, but political symbolism has always been fuzzy on the details.) Just as Lyndon Johnson used his ranch to redefine himself as a product of the West, rather than the South, so Bush has used his ranch to cast himself as a regular Texan, rather than a product of Northeastern privilege, like his father. But while LBJ was born on his family’s ranch and raised in Johnson City, Bush bought his land in 1999, when he was the Republican party’s presumptive front-runner. Crawford had no sentimental pull for him; it was a practical choice. Unlike the Hill Country, the Blackland Prairie still has large parcels of relatively cheap land for sale. Although Bush had never lived in the country and never wore a Stetson in Midland, he now chops wood, drives a pickup, and peppers his speech with folksy turns of phrase. “I haven’t been on the good side of a saw in a while,” he told a reporter who asked him if he had finished a home-improvement project on the ranch. “If I need a hand, I’ll holler.”

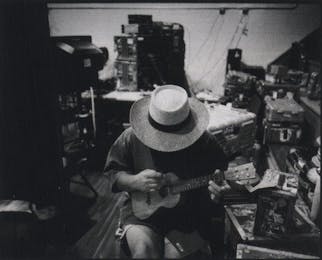

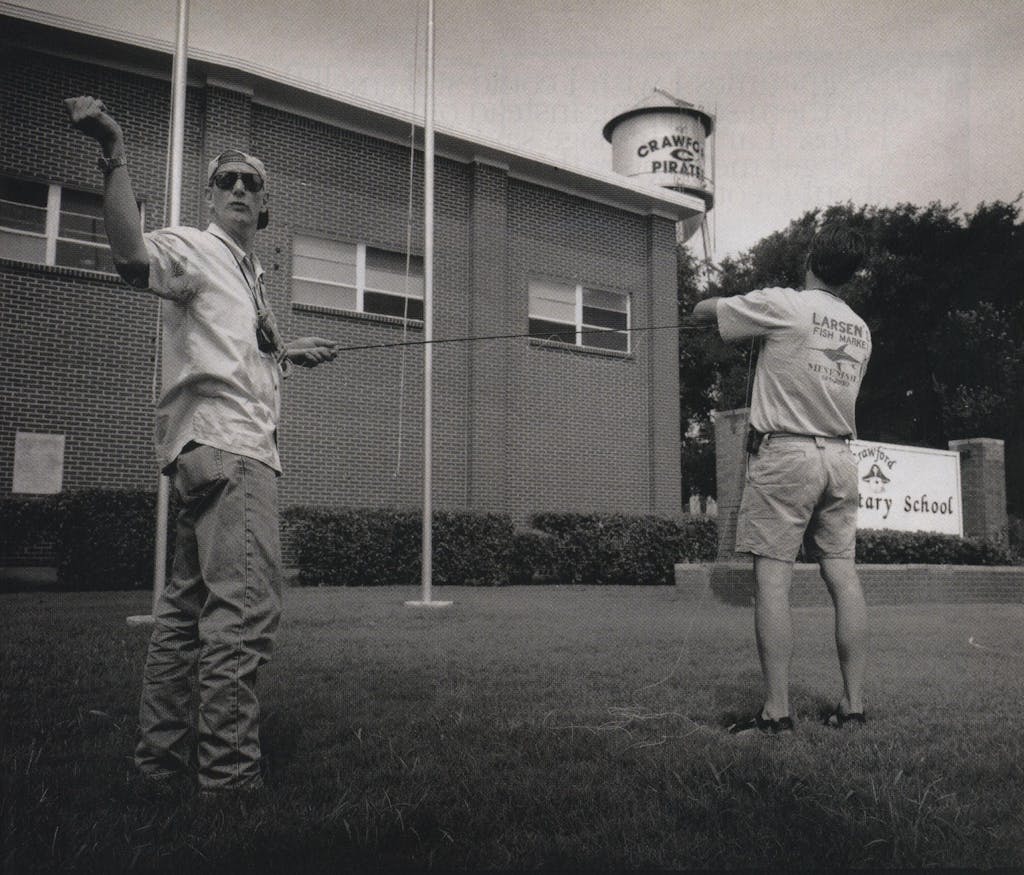

President Bush may not have longed for the salt air of the family compound at Kennebunkport, but the press corps did. “To recreate the feel of Crawford in August, you’d need to wear a wet suit in a sauna,” said Bob Kemper, of the Chicago Tribune. “There’s only one guy who wants to be down here. Our only perk is that the people here are nice. They wave at us with more than one digit, not just the one we’re used to.” In the gym, we looked for diversions: Reporters tossed a football around, photographers practiced fly-fishing on the lawn, CNN cameraman Mike Greene played cheerful tunes on the ukulele. Greene also developed a habit of sunning himself in his rental car with the air conditioning on, dangling his pale legs out the window. “I’m trying to get rid of my North Lawn tan lines,” he explained. At night, the press corps stayed in Waco, unwinding at a sports bar across the street from the Hilton called Cricket’s Grill, where Ari Fleischer was besieged one night by Baylor girls wearing Mardi Gras beads and pink feather boas (“We love you, Ari!”) and where Secret Service agents usually stood, straight-backed, along the bar.

Although President Bush kept busy during his working vacation, taking five trips to ten states where he attended Republican fundraisers that netted nearly $9 million, many reporters in Crawford never saw the man. Mike Allen, of the Washington Post, made a habit of driving past the ranch each day, just to make sure it actually existed. “This administration has an overwhelming suspicion of the press corps,” said Bennett Roth, of the Houston Chronicle, mirroring the comments of many of his colleagues. “We’re viewed as the enemy. The Bush administration does not see it as a public service to keep us informed but as a necessary inconvenience.” In turn, White House correspondents have learned to get their information from less-proprietary sources. At United Nations meetings and G8 summits, they now regularly attend other countries’ press briefings. And when Bush meets with heads-of-state, the press corps often relies on the foreign country’s news services and diplomats to apprise them of what transpired. “Viewing us as an antagonistic press corps and treating us accordingly leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy,” said Kemper, who, in his three years of covering Bush for the Tribune, has never been granted a one-on-one interview. “When everything is so controlled and spun, it breeds suspicion.”

Hopes for a Bush sighting rose during our last week in Crawford, when Prince Bandar of Saudi Arabia visited the ranch. The meeting came during the debate over whether the U.S. should take military action against Iraq, a move that would require Saudi Arabia’s cooperation. National Security Advisor Condoleeza Rice had flown in for the occasion, as had many national reporters, whose newspapers anticipated press coverage of the meeting. But as the hours ticked by that morning, no one from the White House appeared from behind the navy blue curtain. At two o’clock Ari Fleischer arrived to give a press briefing. He was guarded about the substance of the president’s meeting, saying the two men had talked mainly about the war on terror. “On the topic of Iraq, the president stressed that he has made no decisions,” Fleischer said. Then, in response to a follow-up question, Fleischer insisted that “Iraq did not come up in the conversation.” He was more generous with other details. “Lunch included grilled chicken, Mediterranean salad, fresh green beans grown locally, and biscuits,” he said. He was equally forthcoming about what they had worn—”They were casually dressed, wearing jeans and blazers”—as if the diplomatic meeting were actually a bridge party we were covering for the society pages.

“Why was there no media coverage given?” ABC News’s White House correspondent, John Cochran, asked. “As you said yesterday, Prince Bandar is affable and speaks excellent English.”

“Because, when I announced the meeting on Friday, I said there would be no press coverage,” Fleischer said. “And when the president, when he has meetings with ambassadors, [he] does not have press coverage.” Fleischer smiled, trying to smooth ruffled feathers. “I mean, I know it’s Crawford and it’s August and it’s the only game in town in Crawford in August for the president. But that’s part of White House policy. We typically do not have coverage of meetings with ambassadors.” And so the media went back to waiting in the gym, counting the hours until Labor Day and the trip back to Washington.

During his month in Crawford, President Bush did not visit the Coffee Station or attend church services or stop on Main Street to shake hands. He did visit a community barbecue that the White House organized to thank local volunteers, but I was not included in the pool that day. The closest I ever came to seeing Bush on his ranch was watching footage that a friend at CBS News sent me of the president giving a one-time tour of his land in August 2001.

On the videotape, Bush talks to reporters in the dappled light beneath a stand of hackberry trees, looking as relaxed and at ease before the cameras as he has ever been. The videotape was shot seventeen days before September 11, when the burdens of the presidency were not weighing as heavily on his shoulders. Bush is dressed in black jeans, a gray Crawford Volunteer Fire Department T-shirt, and a white Stetson. Around him, reporters jot notes, photographers snap pictures, and cameramen angle for a view as he takes a chain saw to an old tree and carves it into firewood. “If you want the details, that was a dead hackberry: h–a–c–k . . .” Bush calls out to reporters, mindful that his every move is being recorded for posterity. Even in these woods, Bush is surrounded by a sizable security detail; Secret Service agents encircle him as he chops wood, while a doctor and a nurse wait on hand, as they do wherever he goes. Try as he might to escape the strictures of his position, he never can; he is as much a captive of the presidency as Crawford is. “This is one of the few places where I can actually walk outside my front door and say, ‘I think I’m going to go walk for two hours,'” he tells reporters. “And although I’m not totally alone, I can walk wherever I want to walk. And I can’t do that in Washington.”

A week after Bush returned to the White House, I returned to Crawford. Main Street was deserted when I drove into town on a Friday evening, the only sound the faraway cheers that drifted from the high school football stadium. Most of the town was watching the Crawford Pirates trounce the Riesel Indians. In the bleachers, parents and grandparents sat together, rooting for the home team; kids sipped Big Reds and ate homemade vanilla ice cream, which their mothers had prepared before the game; cheerleaders with sun-bleached hair turned cartwheels and beamed at the crowd; the high school band’s brass section blasted “We Will Rock You”; teenage boys slouched against their pickups in the parking lot and flirted with Riesel girls; two volunteer police officers kept watch. After a running back—whose name was actually J. R. Ewing—helped steer Crawford to victory, 41-12, I made my way to the high school cafeteria for the “fifth quarter,” a snack for football players and students that local churches provide after home games. Perry Chapel was sponsoring the fifth quarter that night, and Mayor Campbell stood in the cafeteria, pouring Kool-Aid into plastic cups.

By the time the football players arrived, it was past eleven, and Campbell looked tired after a long week. He receives no salary as mayor, and so he pastors two churches—Perry Chapel and one in Waco—to make ends meet. His biggest problem at the moment was finding the money in the town’s tiny budget to replace its one police car, a twelve-year-old Crown Victoria; its windows would not roll down, its air conditioning was broken, and its only ventilation came through a large hole in the floorboard. The mayor and I talked while he served up nachos to a long line of ruddy-cheeked football players, who strutted around the cafeteria like young warriors. The president was gone, but the headaches that accompanied him were not; Campbell explained that four thousand adherents of Falun Gong, a persecuted Chinese sect, had just filed for permission to demonstrate when Bush hosts Chinese president Jiang Zemin at the ranch this fall. The protesters would outnumber the town’s residents almost six to one. “We’re back to normal,” Campbell said with a weary smile, handing off another plate of nachos to a sweaty Crawford Pirate. “For a little while.”

“I bet ol’ George hates all this nonsense,” said his neighbor, Larry Mattlage, on my last day in Crawford. Larry has never met the president, but his proximity to George W. Bush means that he thinks about the man a great deal. As we talked, Larry leaned on a cedar fence post, squinting in the noonday sun, and pointed out landmarks on the Bush ranch, three quarters of a mile away. On the northernmost side of the ranch ran the Middle Bosque River: a stream of gin-clear water that threaded its way through the prairie grass, past thick stands of cedar elm and burr oak. Farther west was the original ranch house—just a gray blur through Larry’s binoculars—and a fleet of Secret Service vehicles. Out of sight behind a rocky ridgeline lay the scenery that makes this western corner of McLennan County so starkly beautiful: the box canyons, limestone bluffs, caves, and slow-moving creeks that dot the ranch’s two and a half square miles. “I bet George Bush would love to just get in his pickup and drive around his land and clear his mind,” Larry said. “He can’t ever be by himself, and that’s a terrible burden for anyone to bear. A man needs a little freedom.”

The 59-year-old rancher wore an old blue baseball cap pulled down over his eyes; his shaggy salt-and-pepper hair fell against his neck, which was tanned and creased from the sun. A recent divorcé, he lives alone with his old and half-blind dog, Dan, who is bewildered by the F-16s and Blackhawk helicopters that now fly overhead. “It’s like a ground war over here,” Larry said with a chuckle. His ranch, like the president’s, is on Prairie Chapel Road, the main artery that runs through Crawford’s farmland and ranchland. Families of German extraction have worked the land along this road since the Civil War and mostly keep to themselves. “People out here want to be left alone,” Larry said. “We’d rather be scooping manure out of a barn than going to a fancy social event in Waco.” Larry remembers barn raisings and long days picking cotton and relatives who whispered in German. “We’d work our tails off in the fields in the day, and we’d practice football at night, and then we’d cool off in Tonk Creek,” he said. “It was like Mayberry. Everyone knew your parents. Everyone watched after everyone. The night watchman in town had a key to the drugstore. He’d let us in for ice cream after we went swimming, and we’d leave our money on the cash register.”

Staring out toward the Bush ranch, Larry explained that before Bush bought the ranch it had been a hog farm. Nowadays, Larry finds himself feeling nostalgic for the time when the hogs made the air more pungent. “Sometimes I wish I could still smell those hogs and hear them squealing instead of listening to all those F-16s,” Larry said, breaking into a grin. “Don’t get me wrong; the Bushes are fine folks. It’s not about George Bush. It’s about what comes with him.” Larry ticked off a long list of grievances: Secret Service roadblocks on Prairie Chapel Road where he was asked to show identification, property taxes that have become so high that he worries he will have no legacy to pass on to his sons. He and his neighbors are concerned about a proposed new road, to be constructed so that the presidential motorcade will not have to slow down for curves; if built, it would bisect Larry’s ranch and several other ranches. Most of all, he is angry that Secret Service agents speed past him each day without having the common courtesy to wave. “Country people drive slow,” he said. “We’re used to pulling over to the side of the road and visiting. But if you wave at the Secret Service, they think, ‘What’s his problem?’ It used to be you knew everybody when you drove by. Now everyone’s a stranger.”

Larry wanted to give me a tour of his ranch, so we talked in his pickup, lurching down rutted dirt roads. “No one used to talk about politics around here,” he said, steering past Black Angus cattle that lay napping in the shade. “Family feuds have started over all this. You used to be just a neighbor. Now you’re a Republican neighbor or a Democratic neighbor. It’s taken away the closeness of the community.” He pondered this for a moment as he drove, and sighed. “I’ll make some people mad for saying this, but I’ll tell you what really ticks me off. Bush portrays this as his hometown, and it ain’t. He just barreled in here.” We kept driving, past cedar thickets and a pasture studded with blooming prickly pear cactus. As we made our way down meandering cow paths, Larry expressed his hope that Bush will take more of an interest in conservation and using natural energy now that he has shown an affinity for the land. “God owns all this,” Larry said. “We’re just caretakers who are here on this earth for a little while.” We had reached his favorite spot, along the banks of Bluff Creek, a peaceful place shaded by hackberries and horse apple trees. The dry creek bed ran past a white limestone bluff, where the ground was littered with the old arrowheads of Tonkawa Indians who had once camped there.

“It is so gorgeous here,” Larry said. “Just listen for a minute to the quiet.” And so we did. There was no distant rumbling of F-16s or military helicopters—only the wind rustling through the leaves and then a bird calling from far away. Larry turned to me after a long silence and asked, “Am I selfish to want this all to myself?”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- George W. Bush

- Crawford