This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Ten thousand feet above the state he wants to govern, Clayton Williams suddenly bursts into tears. A moment before, I had asked him if it is true, as I had heard, that he cries every time he hears “The Aggie War Hymn.” The answer is swift and anatomical: The mere mention of the War Hymn triggers a fountain of tears. Here sits the Republican nominee for governor—the very man who is traveling around Texas representing himself as the last true cowboy—crouched on the edge of his cushy airplane seat, with his craggy face so wet with tears that it glistens in the bright August light.

The 58-year-old oilman, rancher, and banker is a bundle of emotion. In the course of a 25-minute flight in his maroon-and-white King Air, Williams’ vivid hazel eyes fill with tears three separate times—once over the War Hymn, again when he recalls his father’s death, and a third time when he talks about his grandfather. “I think I get this crying stuff from him,” Williams says, choking on his own emotion. “O. W. Williams was a real tenderhearted sort of man.”

Why does Clayton Williams cry so much? In every case what sets him off is a deep, personal sense of loss that carries over into his politics—loss of his ancestors, of the Texas they once knew that is no more, of the simpler, purer life he led at Texas A&M. It was while Williams was a student at A&M in the fifties that he learned the essential lessons of his life: Country folks are better than city folks . . . Old values triumph over new ones . . . Life is war. Most politicians can be heard to make glib references to the future, but Clayton Williams’ heart is firmly fixed in the past.

On this particular morning, Williams awoke in a cheerful—almost euphoric—mood. He was bound for College Station, his psychic homeland. Before boarding the plane, Williams paused for a moment at the terminal in Austin to greet an acquaintance. “Nora Sue,” he boomed, scooping up the middle-aged woman in his arms. “How ya doin’, honey?”

After landing in College Station, he headed straight for Loupot’s Bookstore to wish the owner, a large and boisterous man named Lou Loupot, a happy eightieth birthday. Amid anti-UT bumper stickers and row after row of black and brown boot polish, Williams looked completely content. He stretched high on the toes of his boots for a glimpse of Kyle Field and pondered the question of the moment. “Do you think,” he asked his old friend, “that we’ll beat the hell out of t.u. this year?”

Two of Williams’ campaign handlers hurried him off to a luncheon speech for three hundred or so members of the Independent Cattlemen’s Association. “One of the joys of my life has been raising cows and working the land,” Williams told the crowd of mom-and-pop cattle producers. The people here were not big ranchers like Williams. The typical person in the room runs less than 100 head of cattle, compared with the 11,600 cattle Williams raises on his twelve ranches in Texas and Wyoming.

“The Lord’s been good to us this year in West Texas,” Williams said, exaggerating his naturally thick twang. “We’ve had a lot of good rain.” Heads nodded. It was, after all, their own voice coming back to them, and the voice of their parents. The whole room was bathed in the warm glow of nostalgia.

The secret to Williams’ appeal is that he isn’t self-conscious or embarrassed about his lack of sophistication and his allegiance to the past. His charm is so seductive that it is impossible not to think of him in the familiar as “Claytie” and be drawn to the comfort of private memories. As he talks, I see a clear image of my own grandfather and suddenly remember how he used to start every conversation with a comment on the weather. “Clouds gathering,” he’d say, his face turned skyward, or “Smells like rain.”

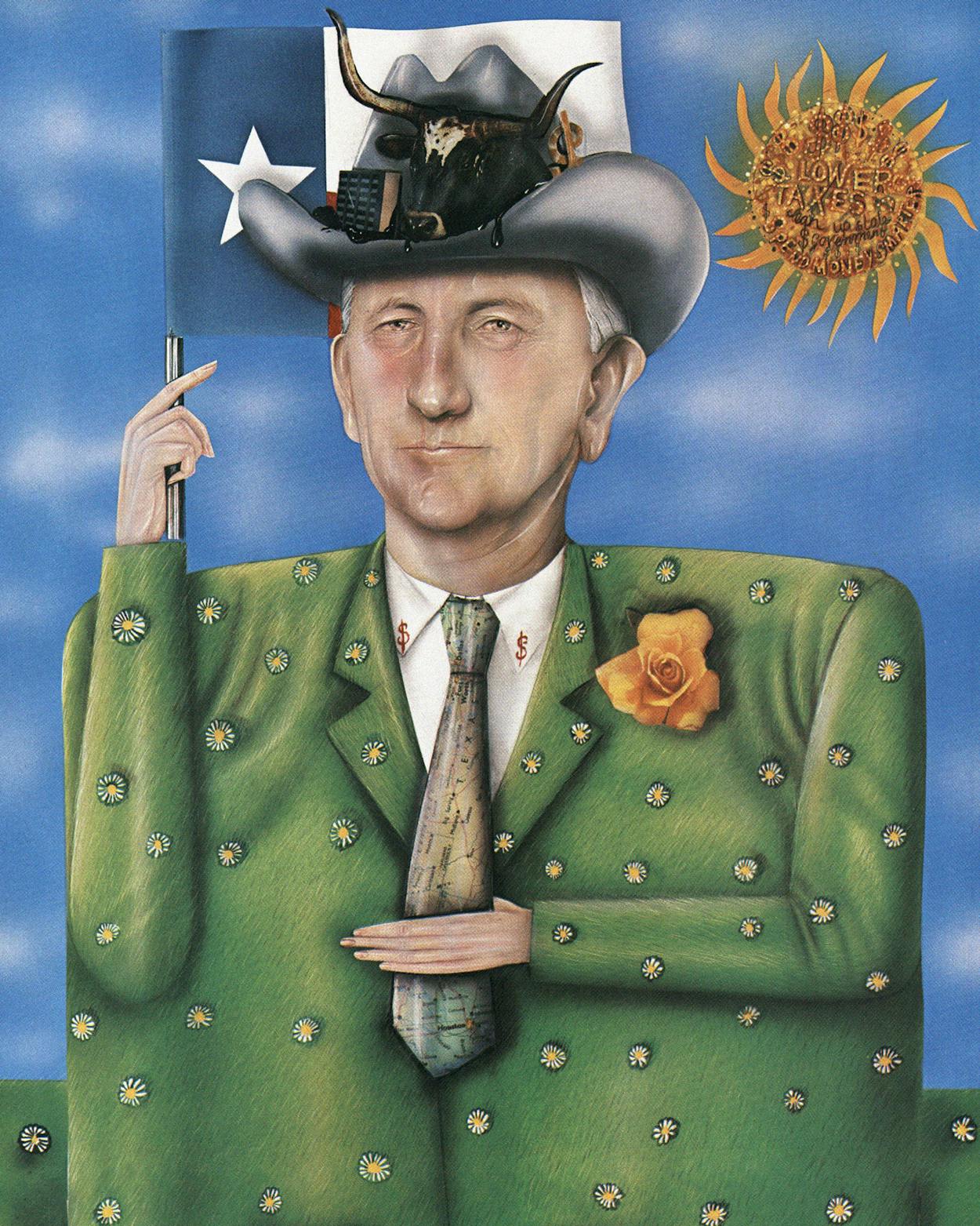

The candidacy of Clayton Williams raises the question of what’s left of the Texas myth. If Williams maintains his summer-long lead and becomes the next governor of Texas, he will win because he has become a physical symbol of our stereotype—the Texas of big oil, masculine ideals, and flamboyant egos. In Williams’ imagination, Texas remains a land of buried treasure, and the only thing separating a man from his fortune is a lack of vision and courage.

For most Texans, that image has always been a grandiose fantasy, but it doesn’t keep us from yearning for the myth. The longing for the good old days is so prevalent that it’s almost a sickness among us. These days Texas is full of people who hate the modern world. After all, Arabs control the price of oil, you can’t tell the names of Texas banks without a scorecard, the Southwest Conference is in trouble, and our own kids—Williams’ included—are on drugs.

When millions of Texans hear Williams on television saying, “I want to make Texas great again,” or “I want to give back to our kids the Texas my father gave to me,” they are drawn to him with a frightened longing. The central question about Williams is whether a person so immersed in the past can govern a modern Texas.

Imparting the values of the old Texas isn’t as simple as it might appear. Williams tried to pass on to his five children—two daughters from his first marriage and two sons (both adopted) and a daughter from his second—the Texas his father gave him. He taught them to ride horses, brand cattle, and respect the land. “The modern urban world tends to separate a man from his sons,” Williams told a Texas Business reporter in 1981. ”But when we’re out on horseback working cows, trying to get them to the same place—when we have the same objective of working the cattle into the pen—they can identify with me. They’ll never be sissies, because they’re learning to become men.” But as hard as Williams worked to keep the old values alive, the modern world intruded on his plan. None of his children work in his business or in traditional Texas professions—oil, ranching, real estate. But the worst blow came when his son Clayton Wade Williams became heavily involved in drugs.

“My boy started using marijuana in December 1985. Things went from bad to worse real quick,” Williams told me. At fourteen, Clayton Wade was kicked out of school. Williams and his wife, Modesta, took Clayton Wade to several psychiatrists and a number of programs that didn’t work before enrolling him in the Dallas-area branch of the Straight treatment program in 1986. In the first therapy session Williams attended, Clayton Wade stood up and told his parents and a roomful of strangers that he had used cocaine, heroin, and LSD, as well as marijuana. Modesta and Clayton were devastated, although Clayton Wade’s confession later proved to be exaggerated.

Those close to Williams recall the long months that Clayton Wade spent in Straight as the worst period in his father’s life. “He would walk around the office with his tail hanging between his legs,” says his longtime secretary, Wynona Riggs. “He felt like a total failure.” Williams himself describes the period as “fourteen months of utter hell.” He says that the first time he and Modesta talked seriously about his running for governor occurred during a three-week hunting trip to Pakistan in 1988, and it was young Clayton’s drug problems that drove him to consider the race. “Fighting drugs is a holy war with me,” he told me.

Williams’ only experience in state politics had come in 1985, when he went to Austin to oppose a deregulation bill sought by telecommunications giant AT&T. Williams hired lobbyist Billy Clayton, a former Speaker of the House and a fellow Aggie and West Texan, to represent his fledgling long-distance company, ClayDesta Communications. For three months they were so visible and inseparable around the Capitol that they became known as Clayton Squared. “He was just so dang gin-u-wine that people loved him,” Billy Clayton recalls. “He figured out he was pretty good at this politicking, and that’s when the first seed for running for governor was planted.”

Facing near-hopeless odds, Williams and Clayton decided to dramatize that ClayDesta, a Texas company, was fighting AT&T, the ultimate Yankee corporation. It was at that moment that Williams first put the Texas myth to work for himself in the political arena. He grabbed headlines by leading a posse of ten cowboys on horseback up the steps of the Capitol. Sophisticated lobbyists scoffed at the tactic, but it worked. Williams won over a handful of consumer advocates who were able to prevent the bill from ever coming to a vote in the Senate.

When Williams became the first Republican to announce for governor in June 1989, the situation looked as hopeless as his lobbying effort initially had. His name was recognized by only 7 percent of Republican voters. His likely opponents had Republican contributors and activists locked up.

What brought Clayton Williams from underdog to front-runner was the same strategy that won the AT&T fight: He used the images of the past to evoke the Texas myth. In mid-September—six months before the primary—the Williams campaign aired the first of five TV spots that touched on many of the symbols of our past, including a campfire, a horse, family photographs, and—in the case of the bustin’-rocks commercial—the romance of Old West justice.

It was Joe Milam, a partner in a Midland ad agency called Admarc, who first got the idea for the famous bustin’-rocks commercial, but it was Claytie himself who came up with the actual slogan after visiting a boot camp in Georgia. The rodeo club from Sul Ross University was hired to portray the teenage drug offenders, and Milam dressed them up in convict costumes. It took nine takes to get the bustin’-rocks ad right. Now wherever he speaks, audiences anticipate the slogan and start clapping even before the words are out of his mouth. “When our kids get on drugs, that’s when Clayton Williams is going to introduce them . . .” Williams tells the cattle producers in College Station, pausing to let the crowd join in, “. . . to the joys of bustin’ rocks.”

The spots accomplished what the Richards campaign has been unable to do: They tapped into our collective identity. Williams used the modern platform of television to build a campaign based on the past. His basic stump speech follows the theme of his television advertisements. It is filled with Texas humor (“When oil was forty dollars a barrel, I used to be six foot four,” says Claytie. “Now I’m four foot six, but I’m still here”), and it encompasses all the old themes that he knows will get an emotional rise from the crowd. He disapproves of homosexuals, vows to veto any state laws that would force school districts to raise taxes, and takes pride in his rural upbringing. The nickname of his campaign barbecue truck is “Lonesome Guv,” and one of the first things he tells audiences is, “I’m a country boy and proud of it.”

By November 1, six weeks after the ads first aired, polls showed that Williams was leading opponents Kent Hance, Tom Luce, and Jack Rains, and the primary was all but over. On election day Williams received 60.8 percent of the vote, leading in 238 of 241 counties.

Then for two months the Williams campaign moved from one disaster to another. Five of his closest business associates and friends had died in a February plane crash, and Williams was in emotional torment. In late March he joked with reporters on his ranch that bad weather was like rape. “If it’s inevitable, just relax and enjoy it,” Williams cracked. He slipped in some polls by 6 percent; irate women (and some men as well) telephoned the campaign office night and day, and even his own mother told him to watch his mouth.

Throughout this period rumors were flying that Williams had hosted “honey hunts” at his ranch—a term that had different meanings depending on the rumor but in general described sexually oriented searches for women on his ranch. In public and private conversations, Williams denied that the rumors had even a germ of truth, but still reporters looked for ways to bring them to light. Then, last April a reporter for the Houston Post asked Williams if he had ever been to a prostitute, and Williams admitted that as a teenager in Fort Stockton he had visited brothels across the border in Mexico. “It was a lot different in those days,” he elaborated inadvisedly. “The houses were the only place you got serviced then.” Williams tried to explain that he was using the word “service” in the agricultural sense—bulls service cows—but the more he tried to explain, the worse he sounded.

For once the myth was working against him. In his public statements, Williams seemed right out of the Texas-is-hell-on-horses-and-women era. It hardly mattered that 30 percent of the top management of Williams’ companies are women, and he has made three of his female employees millionaires. (“Clayton is very sensitive to women,” insisted Kim Jones, a 36-year-old CPA who is Williams’ chief financial officer. “In the workplace, he doesn’t seem to see female and male. All he sees is qualified people.”)

None of Williams’ mistakes permanently crippled his campaign. His advisers adopted a strategy after the rape gaffe to quickly apologize, limit his access to reporters until the story died down, and then use spin to make the best of a bad situation. “People may not like what Claytie says,” campaign manager Buddy Barfield told me, “but they admire him for his candor.”

Williams’ attitude about women raises the larger question of whether he is too tied to the old codes and formulas to lead a modern state. Williams, of course, disagrees. “Tom Luce got kinda stern with me during one of the debates,” says Williams. “He questioned whether Texas can ride horseback into the twenty-first century. Well, my answer to that is you can if you have a good horse.”

In December 1988, when Clayton Williams telephoned his 83-year-old mother at her lovely stone house in Fort Stockton and told her that he had decided to run for governor, Chicora Williams was so surprised that she was uncharacteristically lost for words.

“Mama,” Claytie went on, “what would Daddy have thought about me running for governor?”

This time she knew what to say. “Your daddy would have put his hands over his ears and said, ‘Oh, no, Claytie, not governor.’ And then he would have told you if you’re going to do it, give it everything you’ve got.”

It was the son’s turn to be silent. “Claytie,” said Mrs. Williams sternly, “this thing’s much too big for us. Have you talked to the Lord about it?”

His voice was equally serious. “Yes, Mama,” he told her, “I have.”

In that conversation are the essential patterns of Williams’ life: his motivation to please his father, his allegiance to long-held values, his sentimentality.

“You put down in that notebook of yours that I was not a timid mama,” Chic Williams told me the afternoon I dropped by to see her in Fort Stockton. Sitting there in her living room with its vaulted ceilings, antique furniture, and oak bookcases, she looked like the perfect Texas matriarch. Even though it was August, her beige wool sweater with tiny pearl buttons was pulled tightly around her small shoulders, and her weathered face was immaculately powdered. “Claytie was just a normal, red-blooded boy who loved to have a good time and occasionally got into trouble feeling his oats,” Mrs. Williams said.

He was born in Alpine (the closest town to Fort Stockton with a hospital) in 1931, the older of two children. He grew up during the Depression in Fort Stockton, where his father grew cotton and alfalfa, drilled for oil with mixed results, and later ran for a seat on the county commission to provide his family with a steady income.

“Claytie always wanted to make money,” his mother told me. “When he was fourteen, he talked his daddy into letting him irrigate a little piece of the farm and try to grow some cotton. He hired his younger cousins to help him do the work.”

In high school Williams played football and cornet in the high school band. His nickname in high school was “Maria Gonzalez” because he loved to speak and sing in Spanish. He always got a gold star for regular attendance at Sunday school at the local Methodist church. His father gave Claytie a lot of liberty. When Chic Williams would complain that Claytie was staying out too late at night with his buddies, the elder Williams would tell her, “Chic, turn over and go back to sleep.”

In 1950 Clayton left Fort Stockton to attend Texas A&M, his father’s alma mater. At first Williams hated the hazing he received at the hands of upperclassmen and the regimentation of the dreaded corps. “It’s just like the Army,” he told his father. “I hate it.” His first year he telephoned his parents every week, telling them he wanted to quit school. His father told him he could quit if he wanted to, but Claytie didn’t want people back home to think he couldn’t tough it out.

After graduating from A&M with a degree in animal husbandry, Williams sold life insurance and worked as the only white waiter in the Baker Hotel in Mineral Wells. He managed to save $2,000, and in 1957 he and a partner, John May, formed an oil and gas company. Williams took his place in an office next to his father in a one-story adobe building that was first used by his grandfather O. W. Williams, a Harvard-educated lawyer who came west in 1876 because he suffered from respiratory problems. O.W. had to work as a land surveyor because he wasn’t able to get a job on the frontier as a lawyer.

During the drought of the fifties, Clayton Williams, Sr., had lost the 2,700 acres of farmland he and his brother J.C. worked north of Fort Stockton. In the late fifties and early sixties, Clayton Williams, Jr., went to work building a series of companies that eventually made him successful in the very areas in which his father had faltered: oil and agriculture. He found oil where his father had not—in the O. W. Williams Field, named for his grandfather—and by the mid-seventies he was rich enough to buy back the land his father and uncle had farmed, plus ten thousand more acres.

When Williams moved into the office next to his father, Clayton Senior had begun writing books about the history of the Fort Stockton area. For the eleven years that father and son shared an office, the first thing Clayton Junior heard every morning was one of his father’s stories about the past, and the last thing he saw every night was a giant map filled with tiny pins marking the location of every oil and gas well in the area.

Although his oil and gas business wasn’t booming, it was paying enough to feed three families—Williams’, his partner’s, and their secretary’s. “Nobody went hungry in those days,” recalls John May, Williams’ partner, who still lives in Fort Stockton. “But this image of Claytie as being born to great wealth is just hogwash. It was hot dogs and beer, not steaks and champagne.”

In 1964, when Williams was 32 years old, he changed course. He and his wife, Betty, divorced, and he dissolved his partnership with John May. The marriage had long been in trouble. The high-school sweethearts sought the help of marriage counselors. While Williams was talkative and spontaneous, Betty was dignified and shy. One day Williams’ secretary, Wynona Riggs, went by the Williamses’ house in Fort Stockton and found Betty dressed in leotards and a short skirt, a radical departure from her reserved style. “This is the new me,” Betty told Wynona brightly. But the new Betty didn’t last. The divorce settlement cost Williams half of his estimated worth at the time—$400,000.

Williams was as ill-suited to be May’s business partner as he was to be Betty’s husband. May’s objective was to drill oil and gas wells that were known producers. Williams was driven, even obsessed, to pursue the big gusher. “Claytie kept wanting to go for deeper oil and gas, which took more money than I was willing to risk,” recalls May. “He’s a good guy, but we’re different breeds of men. We just had different objectives.” Both men got what they wanted. Today May raises racehorses in Fort Stockton and drills for oil and gas on the side. Williams continues to pursue the big gusher.

Less than a year after his divorce from Betty, Williams married dark-haired Modesta Simpson, eleven years his junior, who was raised on a ranch near Big Spring. They met in a Mexican restaurant in Midland, where Claytie was singing mariachi songs with the band.

After he married Modesta, Williams moved his base of operations to Midland, where he immediately found himself at odds with the city’s power structure. “Claytie’s style is to come in and start talking about how great he is,” said one Midland old-timer. “That doesn’t go over too well in Midland.” In 1961 he bought the fifteen-story Gulf Building out from under C. J. Kelly, who was then president and chairman of the board of the largest and most politically powerful bank in the city. Kelly thought he had arranged to purchase the building, but Williams bought it before Kelly could complete the deal—and then had the audacity to flaunt his purchase by flying the Aggie flag atop the building. “All in all,” said the Midland old-timer, “Claytie was about as welcome in Midland as a bastard at a family reunion.”

Williams’ personal flamboyance is still evident in Midland. In the atrium of ClayDesta National Bank, the centerpiece of Williams’ 186-acre office park called ClayDesta Plaza, Modesta and Clayton scrawled their nicknames in wet concrete—“Baby Bubbles + Sweet Wheat” it says, punctuated by “Gig ’Em Aggies!”—when the building was first built in 1983. There are not one, but two statues of John Wayne in the bank. Just a block away in Williams’ 115-room hotel, the Plaza Inn, religious pamphlets are piled high on the coffee table in the lobby, and the sign by the swimming pool forbids anyone from swimming in cutoff blue jeans. Everywhere in Clayton Williams’ world are symbols of the Texas myth and its values.

Just as Williams is running for governor to keep the past alive, his business career is deeply wedded to the past. For most of his life, Williams has relied on the old Texas formula for amassing great wealth: He runs cattle on top of the land and extracts oil and gas from beneath it.

In 1967 Clajon, his pipeline company, got its first major break when Williams signed a contract to sell natural gas to the City of Fort Stockton. But growth was slow. Three years later, Clajon was still a small company—just four employees and 35 miles of three- and four-inch pipe. His exploration activities got off to an equally fitful start. Williams drilled a series of dry holes that must have severely tested his faith in the myth. But he kept buying new leases and drilling new wells. “Our premise was to hit early,” says Wynona Riggs. “We might not have been the first to drill in a field, but our strategy was to be the second and offer higher royalties to landowners.” Claytie knew all the ranchers around Fort Stockton, and he was in a good position to broker leases. In the oil patch Williams was known as a plunger—he was quick to jump at a deal that he thought was good.

On New Year’s Eve, 1975, Williams finally got his gusher. A deep gas well, Gataga No. 2, blew out in Loving County. The blowout was so big that the tiny county seat of Mentone had to be evacuated. Within days Gataga was producing $49,000 worth of gas daily, and Williams became big-time rich. He used the money to borrow millions more to buy hundreds of thousands of acres of oil and gas leases, as well as almost 500,000 acres in Texas and Wyoming.

In 1981 Williams began to be uneasy about the oil and gas business. On a hunting trip in the Yukon, he took stock of his overall situation: Oil prices were softening, drilling costs were soaring, and he owed about $500 million. Williams suddenly felt the full load of the debt he was carrying. “Hell,” he told himself, “I’m not smart enough to operate in this environment.”

The decision to sell off his oil properties wasn’t entirely his own. He was beginning to feel pressure from the lenders—Williams was on the board of MBank in Dallas—as early as 1981 to stop borrowing so much money. Nevertheless, the decision was superbly timed: Williams had seen what many in Texas did not until it was too late. He sold 152 wells in the Burleson County section of the Austin Chalk to a Denver-based company called Petro-Lewis for $110 million. The wells began to decline in productivity almost immediately. Later, Petro-Lewis sued Williams, claiming that Williams’ pipeline company and gas processing plants had wrongly underpaid Petro-Lewis. The case was settled on secret terms five days before it was scheduled to go to trial in January 1990.

The Petro-Lewis case is important because it illustrates a disturbing pattern in Williams’ career as a businessman. At crucial steps of Williams’ business life—including his decision to sell out in the Austin Chalk—he has been sued for wrongdoing. The merits of the charges are impossible to determine because the lawsuits were always settled—usually by Williams paying an unspecified amount and the plaintiffs promising never to discuss the case. Many of the lawsuits involved Clajon, his pipeline company. Under Texas law, pipelines are common carriers and must take gas fairly from all producers in a field. When the gas market turned bad in the mid-eighties, several producers sued Clajon for giving preferential treatment to Williams’ own wells. When I asked Williams about it, he insisted he never used Clajon to market his gas at the expense of his competitors. “I gave my people strict instructions to treat my gas the same as everybody else’s, and I believe that’s exactly what they did,” Williams said.

After Williams reduced his involvement in the oil business, he tried to diversify. Between 1980 and 1984, he branched out into banking (ClayDesta National Bank in Midland) and real estate (ClayDesta Plaza), and he even started a company that sponsored safaris. The most ambitious project was the start-up in 1984 of ClayDesta Communications, a digital long-distance telephone network designed to link most major Texas cities.

But the bust turned Williams’ attempts at diversification into disaster. Williams’ bank ran into hard times, the value of his real estate dropped, and eventually ClayDesta’s customers couldn’t pay their telephone bills.

Then Williams was once again accused of cheating in a lawsuit. In 1987 Ed Moriarty, one of the first employees of ClayDesta, filed a lawsuit against Williams, claiming that the business plan for ClayDesta was his and that Williams in effect had stolen it from him. In the lawsuit, Moriarty said that he first took the idea of a long-distance company to Williams and that one of Williams’ top executives told him Williams wasn’t interested in financing other people’s ideas. According to Moriarty, Williams’ executive offered him 30 percent equity in the new company, and Moriarty accepted. ClayDesta was formed in 1984. Two years later Williams fired Moriarty.

In a deposition given in 1987, Williams said that he told Moriarty in a telephone conversation that if he pitched in and helped build the company, he would share in the net profits—but he denied that the idea for ClayDesta was Moriarty’s. “I fired him and gave him fifty thousand dollars in severance because he wasn’t doing his job,” said Williams. ”That’s more than the man deserved.”

Williams settled the lawsuit with Moriarty in 1989 for what Moriarty’s lawyer called “a very respectable amount.” The terms of the settlement were made confidential at Williams’ request. Williams takes pride in the way he treats his employees—most of his friends are people who work for him—but the Moriarty lawsuit reveals another side of him: When someone gets on his bad side, all goodwill is forgotten.

By 1987 Williams was mortgaged to the hilt and under pressure from banks. Reluctantly, he sold Clajon, the pipeline company he started in his grandfather’s office, for $230 million. Two years later, in March 1989, he sold ClayDesta Communications for $43 million—a net loss of $13 million. Later, Williams said of the loss, “I’m pretty proud that I was able to build it from nothing to a company that sold for forty-three million dollars in one of the worst economic climates that Texas has ever had.”

With the money he received from the sale of Clajon, Williams paid off all but some $200 thousand of his $500 million debt. He reportedly accumulated more cash early this year from the settlement of a lawsuit against Valero, the San Antonio–based pipeline company. He immediately started buying new oil leases in the Pearsall section of the Austin Chalk. The one time that he ventured into the modern world of high technology, he had lived to regret it. Now Claytie Williams is right back where he started: in oil and ranching—the womb of the myth.

For Clayton Williams, the downside of the Texas myth is a small piece of ground in Fort Stockton, dusty and dry, covered with rusty wire, and littered with potato-chip packages and other garbage. This is where Comanche Springs once emerged from the ground. In 1857 members of the Leach wagon train described Comanche Springs as “a beautiful spring some 10 or 15 yards wide, about 10 feet in depth, clear as crystal and running at a mill tail rate at a few miles and then losing itself in the earth.” For nearly thirty years, Clayton Williams and his father before him have pumped so much water out of the ground to irrigate their farmland west of Fort Stockton that the springs are now dry.

Comanche Springs is Williams’ Achilles’ heel. Nothing else in his public life so graphically illustrates the conflict inherent in his frontier values: the right of a man to exploit nature to accumulate vast wealth versus the public interest. When I asked Williams if he thought Comanche Springs would flow again if he stopped pumping 30 million gallons of water a day to irrigate twelve thousand acres of farmland, he told me, “They might, but I’m not going to do it. It’s my land, and I have the right to use the water.”

For as long as Clayton Williams has lived, Comanche Springs has played an integral part in his life. Williams learned to swim in the springs. The springs surfaced just around the corner from his boyhood home in Fort Stockton and right next door to his grandfather’s office.

In the summer of 1954 Williams’ father won a case before the Texas Supreme Court that affirmed landowners’ right to own and control the water beneath their land and to do whatever they want with it. That case still stands as law in Texas. Because of that ruling Comanche Springs stopped flowing in 1962, and the state today remains powerless to protect the Edwards Aquifer from being pumped dry or the area near the San Jacinto Monument from land subsidence caused by industrial wells.

Thirty-six years after the case, Kirby Warnock, a 38-year-old grandson of one of the 150 downstream farmers whose land dried up before their very eyes, is still fighting the battle over Comanche Springs. His farm east of town is crisscrossed with a network of empty irrigation ditches and floodgates. Where once his grandfather grew four to six cuts of alfalfa a year, there is nothing but brown, parched earth covered with mesquite and prickly pear cactus. “On my property what water we have is so alkaline that it kills the grass when we water it,” said Warnock. “We now have to get our drinking water from Balmorhea, sixty-two miles away, because Clayton Williams’ selfishness has made our wells unfit for use.” Once Warnock’s father told him, “I get mad every time I look out into that dried-out pasture.”

After unusually heavy rains in 1986, Williams and the other farmers in the long green valley west of town were able to reduce their pumping. Lo and behold, Comanche Springs started flowing again. A citizens’ committee tried to create a local water district to regulate pumping in the area, including the pumping that is done on Williams’ land. But Williams opposed the water district, and a decision was made to delay the whole idea until the United States Geological Survey completed an investigation of the aquifer and its effects on Comanche Springs. In the spring of 1987, Williams and the other farmers cranked up their pumps, and Comanche Springs went dry again. Meanwhile, Fort Stockton is still waiting for the USGS to make its report.

Comanche Springs is the only thing Williams gets defensive about. “I’m a businessman. I’m a cowman. I’m a conservationist,” he told me. “I didn’t dry up those springs. I bought the land. It’s mine, and if I didn’t pump water, it wouldn’t be worth anything.” Would Williams support regulation of other people’s groundwater, since he has opposed regulation of his own? “I hate to dance around with you,” said Williams, “but my general philosophy is we need some realistic conservation, and we may even need regulation, but regulation with reason.” Williams grew so animated as he talked that he took my notebook from me and started drawing a picture of an underground aquifer. “You know,” he said, “these aquifers are a mysterious thing. Nobody’s sure exactly how they work.”

The mood on Nicholson Heirs No. 1, a large well just outside Pearsall in what is now the hottest oil play in Texas, was ecstatic. Williams’ maroon-and-white tanks were storing oil at a comfortable rate of 380 barrels a day. Nearby, on Williams’ drilling rigs, the Aggie flag was popping in the hot August wind. The oil-field hands were in a downright festive mood. Before Iraq invaded Kuwait, the price of West Texas intermediate had been hovering between $15 and $18 a barrel, and these men weren’t sure they had a future in the oil patch. Suddenly oil was selling for $28, $30, who knows, maybe $40 a barrel, and what went on at this drilling rig and the thirty others that fly Williams’ A&M flags in South Texas was a matter of national security. “You wait,” one roughneck told me. “We’re going to kick us some Arab butt.”

The boom was created even before the Persian Gulf crisis by horizontal drilling, a technique that is based on drilling sideways into the earth instead of straight down. Horizontal drilling was proven here in the Austin Chalk in 1988 after Oryx Energy, an oil company based in Dallas, took a well that was producing only eight barrels a day and ran production up to a thousand barrels a day. Claytie wasn’t the first one in on this boom, but—as was his rule years ago in West Texas—he was the second one in, and he immediately put twelve land men into the area buying up three hundred leases. Now he has 140,000 acres under lease near Pearsall, and his business plan—which enables him to make a profit with oil selling for $18 a barrel—calls for him to drill three hundred wells by 1992. If the price of oil stays at $28 a barrel, Williams will be richer than he was before the bust.

Milt Shepherd, the geophysicist in charge of Williams’ operations in South and East Texas, pointed to a sleek oversized pump jack at work in a pasture off Interstate 35. “There’s an example of new technology at work,” he told me proudly as we whizzed along the road in his Suburban. “We’re using the new larger pumps down here because horizontal wells require greater lift capacity.”

Everywhere there were signs that the boom was real. Large trucks rumbled down side roads, creating traffic jams. The sky was full of smoke from flares on wells. In the morning, we passed an empty place in the road where workers were setting up a new pipe-and-parts yard. By the afternoon, the place was open for business. Little white trucks carrying $500,000 worth of seismic equipment could be spotted in deserted fields.

While we were driving around the countryside, Shepherd’s car phone rang. Williams was calling between campaign stops in Houston. “I sure am jealous of you guys,” Claytie told Shepherd. “There’s no place I’d rather be than in that oil patch.” Just then Williams told Shepherd he would have to call back because T. Boone Pickens was calling on another line. Within five minutes Williams was back on the line, his mood all business. Shepherd told him that two more wells had been completed that particular day. “Great,” said Claytie. He went on to explain that he was talking to Tony Sanchez, an oil operator—and a prominent Democrat—about the governor’s race, when Sanchez mentioned he might like to be a partner with Williams in one of his Pearsall wells. Could Shepherd follow up and negotiate the deal? Shepherd told him that he would get right on it. “Don’t drill any dry holes,” said Claytie before getting back to politics.

The play in Pearsall represents Williams’ future. He is proud of the new equipment and technology and uses it to refute the argument that he is hopelessly bound to the past. “This boom is tied to technology,” Williams told me. “There’s nothing old-fashioned about it.” But even in the heady atmosphere of $28-a-barrel oil, it is impossible not to be skeptical. Texas is the most costly producer of energy in the world, and as long as our future is dependent on a high price of oil, then we are doomed to living off of faraway crises.

Beyond the question of whether oil should be the business of Texas is the question of whether oil should be the business of Texas’ next governor. Tony Sanchez is not the only oilman in Texas who will want to be in business with the governor of Texas. Some of them, inevitably, will want something more—an appointment, perhaps, or the resolution of a problem at a state agency. This is a formula for scandal. Williams should either divest himself of his oil holdings or put them in a blind trust, as Bill Clements did. So far, at least, he has said he will do neither.

To be face to face with Clayton Williams is to be face to face with the full force of the Texas myth. It is, for the most part, a myth that has served us well. It has given us our uniqueness, our character, and a sense of unity found in no other state. But while the rest of the country has changed in the eighties, the myth has stunted our growth and kept us tied to a rural past that can provide for fewer and fewer people. All of Clayton Williams’ oil wells won’t fix the problem of the state’s outmoded economy; all his paeans to hard work and independence won’t solve the problems of a state welfare system that has just been saddled with $1.5 billion in new obligations by the federal government; all his homilies to local control of education won’t solve the problems of a public school system that is now being run by the courts; all his reverence for the principle that ownership of land is a sacred right won’t solve the problems of water shortages in El Paso, the Panhandle, San Antonio, and most of Texas in between. Texas’ infatuation with its myths has produced a dominant strain of politicians who think more about the state’s past than its future. And no one fits that description more than Clayton Williams.

“I’m not going to force anybody to wear cowboy hats, jeans, and act like I do,” said Williams. “But I’ve noticed that most people who hang around me long enough wind up owning a pair of boots.”