This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

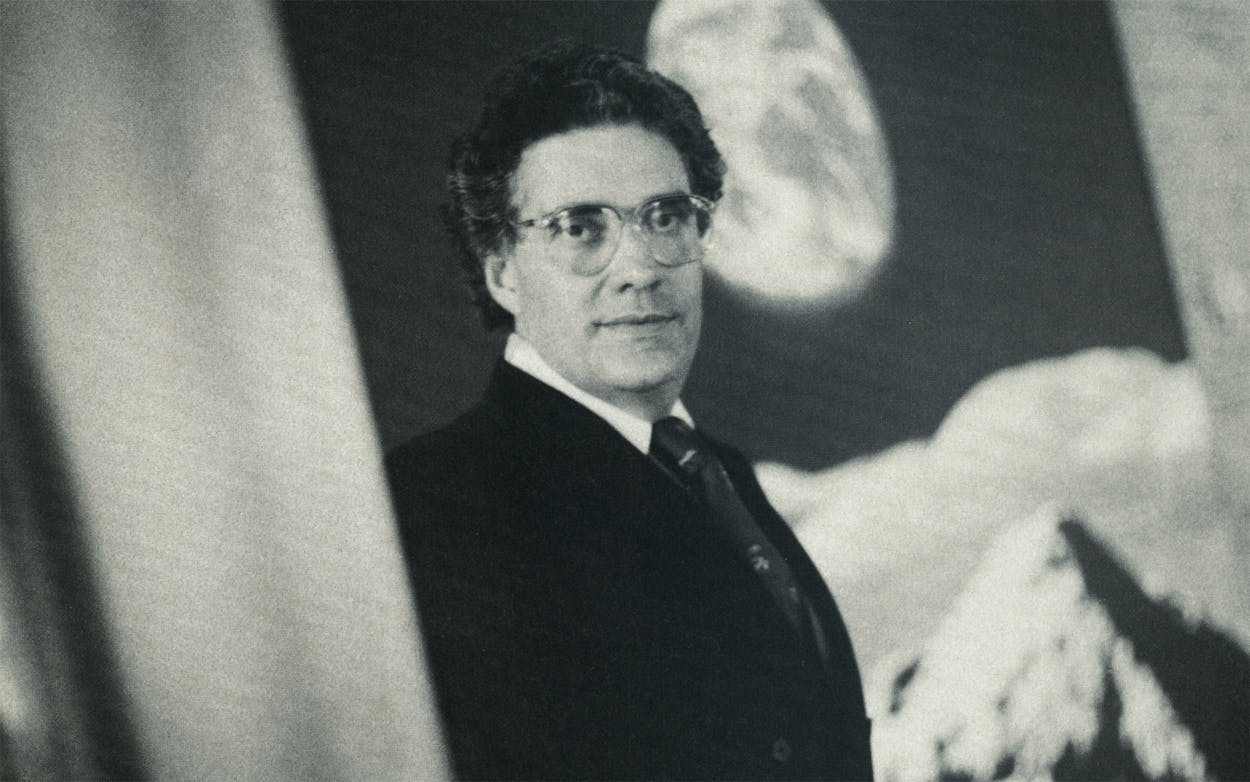

Like most captains of industry, William N. Agosto, the founder and president of Lunar Industries, is a man of vision. So when Agosto steps out upon his balcony at night to ponder the full moon as it rises above his Clear Lake apartment complex, he sees more than a pretty bowl of wavering light. Agosto sees cement.

No matter that the moon happens to be 238,857 miles from earth. The lunar surface is a quarry in Agosto’s mind, an exploitable new world loaded with raw materials for metals, ceramics, glass, and, especially, cement. There are those who roll their eyes. Agosto knows that. There are nitpickers who say that his plans for mining lunar cement are wildly impractical. So Agosto has taped inspirational messages on the walls of his tidy study. One reads “You can do it!” Another: “Grab the world by the tail!”

Agosto isn’t a flake. Formerly a principal scientist with Lockheed, he is one of the few engineers in the world to have done extensive studies on the industrial potential of the moon’s surface by using lunar samples collected during the Apollo landings. Agosto has held moon rocks in his hands, and his enthusiasm can be contagious. He’s convinced that billions of dollars can be made in space, and he’s not alone. His colleagues include aging astronauts, technocrats, high-risk capitalists, former NASA engineers, futurists, refugees from the oil business, who are all betting that Houston will be the terrestrial base for this new economy.

Don’t, however, rush out to the mall and look for “Made in Space” products yet. In a brochure designed to sell Houston to the fledgling space industry, the Houston Economic Development Council published a list of companies and research institutions in Houston with an interest in space commercialization. The tally came to 44, though many on the list were large aerospace companies like Martin Marietta and Morton Thiokol, which maintain only branch offices in Clear Lake so as to be within easy walking distance of their favorite client, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The actual number of homegrown enterprises and consortia committed to space commercialization is closer to a dozen—maybe.

Their business plans read like scripts from science fiction films. Two engineers in Houston are designing reactors that will extract oxygen from moon rocks, and as Agosto presses ahead with his scheme for mining lunar cement, other visionaries are planning to plug into NASA’s space station, which is already in the final design stages. Attached like outbuildings to the $8 billion space station will be industrial pods that provide commercial manufacturers with the most unusual workplace known to man, a weightless environment of drastically reduced gravity, where lifesaving pharmaceuticals will be made in vats not test tubes, where huge but delicate crystals will be grown as they never are on earth, and where metal alloys will mix beautifully, free from the uneven settling caused by the earth’s gravitational tug.

If all the space buffs’ dreams come true, Houston’s commercial role will be similar to that of the Johnson Space Center; the city will provide the foundation—brains, management, capital. But because no big aerospace companies are in the area, it won’t be manufacturing any rockets.

The grim spectacle of the fireball that was the space shuttle Challenger hasn’t tabled the plans or dimmed the enthusiasm. The shuttle disaster may even boost commercial efforts in space, as private companies hustle to take up the slack by offering bargain-basement-priced launch services for grounded satellites waiting for a spot in the shuttle’s cargo bay or by developing their own version of NASA’s again-delayed space station. The true believers see the Challenger tragedy as a test of the young industry’s mettle and a reminder that the cost of exploiting space will be no less dear than that of crossing a continent in covered wagons or etching it with railroad tracks. A former astronaut now involved in commercial space efforts puts it this way, “If the explosion scared people off, they weren’t in the right business to begin with.”

Travel in the right circles, and Houston does seem to be gripped by space fever. At the University of Houston–Clear Lake there is a phone line that is answered cheerfully, “Space Information. May I help you?” The university also offers a class called “Our Future in Space” taught by a forecaster who hopes to win a $200,000 NASA contract to set up a data base on commercial space efforts for the Johnson Space Center. Lamar Savings runs advertisements as the first bank in space, complete with a burly guy in a pod using robotic arms to dig for rocks on a meteor.

Each month about 125 people, many for the first time, attend the Space Foundation’s Space Business Roundtables in downtown Houston. They each pay $22 to eat chicken Kiev and listen to astronauts, policymakers, NASA engineers, and space entrepreneurs discuss earth mapping, solar exploration, artificial intelligence, and plans for a space-based equivalent to Federal Express. The Houston chapter of the Space Foundation has spun off groups in Austin, Dallas, and Washington, D.C. At the Houston Club last January, an audience sat attentively, brows furrowed in polite concentration as Kenneth Demel, a representative from the Johnson Space Center, lurched into an esoteric spiel about the advantages of manufacturing in space, complete with a blitz of visual aids and much technical verbiage about hydrostatic pressure, fluid dynamics, pumping rates, and superior crystal growth. Unfortunately, many of the people attending the roundtable—lawyers, accountants, public relations types, investment brokers, realtors—had absolutely no idea what the man was talking about, until he used some magic words: think of NASA’s planned space station not as an expensive government experiment floating in an inky-black void but as prime real estate in space. The professionals perked up; they might not know much about hydrostatic pressure, but they do know about real estate.

Hanging in the Clear Lake offices of Space Industries, a Houston company that plans to launch a commercial manufacturing and research plant into orbit, is a photograph taken by former astronaut Joseph Allen, now the firm’s executive vice president. An astronaut floats above the open cargo bay of the space shuttle as it orbits the earth. He is holding up a sign. The sign reads, “For Sale.”

James Calaway, the redheaded 28-year-old vice president and a founding member of Space Industries, is a fitting symbol for Houston’s high hopes. “If space is the final frontier, who better to exploit it than Texans?” he asks. Calaway’s father was an oilman who made his fortune drilling wildcat wells. The younger Calaway thinks of space as a wildcatter’s long shot, an industry full of deadly unknowns and high risks but with potential for an astronomical payback. “Billions of bucks are going to be made in space,” Calaway says. “And still people are sitting around, shaking their heads, and saying it’ll never happen. Ha! Those are the same kind of people who are always left behind.”

To be sure, nobody in Houston wants to be left behind in the present. With the price of West Texas crude dropping so low, everybody is scrambling to diversify. A cynic might say that Houston has been a little slow on the uptake, but the city is making up for lost time. It’s so hungry that the powers that be appointed Gerry Griffin, former director of the Johnson Space Center, as president of the Houston Chamber of Commerce in January. They could have picked an oilman or a developer, but they didn’t.

An astute public relations man, Griffin has a reputation as a personable and goal-oriented administrator. With a background in government service and high technology, Griffin brings to the post a more polished, forward-looking image than that of his predecessor, former mayor and recent mayoral candidate Louie Welch. Griffin understands the new mandate: “I was brought aboard specifically to help the city move toward the future, to make Houston a high-technology city.”

Studies conducted by the consulting firm of Arthur D. Little and funded by the Houston Economic Development Council targeted space as one of two 21st-century industries (the other was biotechnology) that the city should cash in on. “We’ve got all the ingredients to be a major player in space,” Griffin says, pointing out the proximity of the Johnson Space Center and the Texas Medical Center, in addition to the solid base of engineering expertise left over from the halcyon days of oil and the presence of moneyed individuals who understand the risks of wildcat investment. To get the ball rolling, the development council allocated $500,000 to woo space-related industries, money that has been spent on trips, mailers, promotional booklets, proposals to NASA, and even a poster that depicts Houston’s skyline on a space station orbiting a blue-marbled earth.

Experts predict that space could support a $100 billion business by the year 2000. That would be nice. Marc Vaucher, program manager at the Center for Space Policy (a private consulting firm from Cambridge, Massachusetts, that has contracts in Houston), warns that predictions of earnings are meaningless, adding that one mistake consistently made by young space companies is their optimism about timetables.

Despite these dreams for orbiting space factories serviced by weekly shuttle flights, the state of the space industry in Houston is represented best by ventures like Agosto’s Lunar Industries, a small company with a big idea but little capital, no customers, and no income. Most space operations in Houston support fewer than ten employees. Agosto’s company is tiny; he and his attorney are the only employees, and both are part-time. Offices are spartan; Lunar Industries operates out of a back room in Agosto’s apartment. Overhead is almost nonexistent. Peek into the typical space venture, and you will see an answering machine and two engineers sharing a personal computer.

Agosto’s scheme for getting cement from the moon is admittedly grandiose. Equally ambitious is Space Industries’ plan to put a factory in orbit. Because space-based manufacturing won’t become the rage until processing facilities are up there, Space Industries president Maxime Faget hopes to have his space plant in orbit by early 1990, at least four years before NASA’s space station goes on-line. About 35 feet long and 14 feet in diameter, Faget’s factory will be deployed by a shuttle into a low orbit some 230 miles above our planet. Unlike NASA’s space station, Faget’s free-flier won’t be permanently manned, but it will be serviced periodically by specialists who flip switches, harvest products, restock manufacturing systems, and take out the garbage. Faget had struck a unique fly-now, pay-later deal with NASA, his previous employer. Last August the space agency agreed to provide two and a half shuttle cargo bays to place two of Faget’s factories into orbit, a service valued at more than $175 million. Payment will be deferred for two years, after which Space Industries will begin paying NASA 12 per cent of the company’s cash flow until the debt is paid. The deal was a clever piece of work, and the young company is already the most talked-about space venture in Houston and perhaps the country. Part of Faget’s pitch is that all the technology going into his space factory is off the shelf. “We’re not going to do anything that hasn’t already been done by NASA,” says Faget, who supervised NASA’s development of manned space flight for twenty years. “We’re not reinventing the wheel. We’re just going to use the goddam wheel for a change.”

Faget, a small but intense bald-headed man with no love of bureaucracy, says he agreed to go in with Calaway to start Space Industries after his NASA colleagues told him that if he didn’t get a space facility in orbit, nobody would. NASA and Faget have been planning to deploy an orbiting station in one incarnation or another since the Mercury missions.

Ventures like Faget’s require enormous capital. The project will cost between $250 million and $300 million, and Space Industries officials aren’t saying how much they have raised so far. At this point most space companies in Houston subsist on government contracts or meager research grants. Agosto supports Lunar Industries by doing consulting work, much of it for a Japanese construction company. The few companies with seed money obtained it by tapping wealthy individuals and friends of the family.

Space Services, for instance, has survived because its founder, millionaire real estate developer David Hannah, has deep pockets. Just how deep is being tested. Six years ago Hannah started the first and only private company in the world to launch its own rocket into outer space. The new business arrived on the scene with, well, a bang. Its first rocket, the Percheron, exploded on the launchpad at Matagorda Island during a preflight test in 1981 (see “Mr. Hannah’s Rocket,” TM, November 1982). But its second expendable launch vehicle, Conestoga I went up without a glitch in 1982. Conestoga I, however, was the company’s first and last successful rocket.

Today Space Services is housed in a low-slung office building on the Gulf Freeway in southeast Houston. For $14.5 million, it will deploy a customer’s spacecraft into low-earth orbit, about 150 nautical miles above Houston. “You show up at the launchpad, and we’ll get you where you’re going,” says Donald “Deke” Slayton, president of Space Services and a former astronaut who races jets on weekends to relax. But that just isn’t happening. The company has that frayed-at-the-cuffs look of a business in trouble. It has only ten employees. One contract bid after another has been shelved, and the company has had to acquire a subsidiary to support the parent. In six years of operation, it hasn’t made a dime.

“Nobody’s knocking at our door,” says Slayton, a survivor from the days when space was conquered by laconic but steely test pilots, not schoolteachers and senators. Slayton believes in the space industry but isn’t sure when it will get off the ground. He rattles off a litany of problems. Money is tight. Risks are too high for bankers. For venture capitalists, who insist on seeing a return in three to five years, the time line for commercial efforts in space is too long; most schemes will take at least eight to ten years before they turn a profit. But even if a venture capitalist decides to invest, the amount of money required is prohibitive. The large aerospace companies have shied from high-risk ventures. “Forget those guys,” says Slayton. “The aerospace industry won’t do a damn thing unless the government pays for it.” Also, casualty insurance is almost impossible to place; in the last eighteen months the space industry has incurred more than $600 million in insured losses.

Worst of all, Space Services can’t beat NASA, whose prices for satellite launches are, in effect, federally subsidized to be competitive with Ariane, the three-stage expendable launch rockets developed by the multinational European Space Agency. Another problem for Space Services is that the largest satellite it can launch weighs about three thousand pounds. Many of today’s communications satellites weigh close to five thousand pounds, in addition to the five-thousand-pound booster rockets used to propel the satellites from the space shuttle’s low-earth orbit into the more distant reaches of the Van Allen belt. “Business is just going real slow, much slower than we thought it ever would,” says Slayton.

The availability of the space environment is so new that potential customers aren’t certain yet how to use it. Agosto, whose most-optimistic lunar-mining dates fall in the next century, has no customers. No matter. Space Industries doesn’t have clients signed yet, and it plans to be in orbit by the end of the decade. Hannah’s Space Services is not doing much better. After six years, it has only one customer, the Celestis Group from Florida, which plans to dump the cremated remains of 10,000 people into a shiny satellite and have Space Services blast the dear departed into near-eternal orbit.

“Getting funds is kind of a catch-twenty-two,” says Bill Huffstetler, manager of flight projects and the man in charge of commercial space programs at the Johnson Space Center. “To get customers, you need credibility. To get credibility, you need customers. Nobody wants to be the first to sign on.”

The only companies making money are doing it on earth by providing near-term terrestrial services. Eagle Engineering, perhaps the best known, works out sticky technical details for entrepreneurs like Faget and then drops the data, along with the bill, on its clients’ lap. One service company, Space Test, helps clients get their experiments onto the shuttle. Another provides software to solve space-based engineering problems. There’s even a company that will rent out an astronaut for a speaking engagement.

Cashing in on the final frontier isn’t a novel idea. The large aerospace companies have been under continuous contract with NASA since the civil space agency began operations 25 years and $200 billion ago. Each year NASA spends $7.5 billion, and the military goes through another $10 billion on space-related projects. The new satellite communications industry generates about $3 billion a year. Then there are the spin-offs that NASA loves to tout, about 12,000 products at last count, everything from Teflon frying pans and Velcro cuffs to solar panels and high-speed computers.

Exactly how the private space industry in Houston is going to make money isn’t clear. It has no track record, no success story to point to. Space Industries’ Calaway says his company hopes to rent space in its 2500-square-foot factory for $100 million a year, though it is doubtful that any one company would dominate the entire capsule for that long. Potential customers are companies like 3M, which has sponsored shuttle experiments to test an organic film that uses light to carry large volumes of information at high speeds. Two other possible customers include NASA and the military. The company hopes to get its first rent check in 1990.

More potential customers for the space plant are in the biotechnology industry. The Houston Economic Development Council thinks the city is in a good position to exploit the biotech sphere by focusing on pharmaceuticals, genetically engineered products for agriculture, and bioprocessing technology. All three technologies can be enhanced in outer space, where zero gravity—what scientists call microgravity—can be used to make superior metal alloys, huge crystals, and vats of ultrapure drugs.

Houston is suddenly so bullish on space-based biotechnology that it is making the new science the cornerstone of its bid to be named one of NASA’s five Centers for the Commercial Development of Space, a package deal awarded to a research consortium with commercial aspirations. The award is coveted because it includes guaranteed room on upcoming shuttle flights and $3.75 million in seed money over five years. More important than the government’s money, however, is the credibility that winning one of the centers would bring to Houston.

Houston’s first bid for a center was turned down by NASA in 1985. Space City was passed over for centers in Cleveland, Nashville, and Huntsville, Alabama, and two centers in Birmingham, Alabama. Despite much carping from Houston’s business leaders, there were good reasons for the rejection. The city’s proposal was based on the creation of a brand-new research institute. And the proposal, which NASA deemed too broad, focused on three distinct research areas: biotechnology, material processing, and robotics. NASA didn’t feel confident about the newly created consortium and fretted that Houston didn’t have enough industry participation, one of the main aims of the program. Huffstetler of the Johnson Space Center says that four of the five centers were already involved with microgravity research programs and had near-term results and established institutes at hand, in addition to strong support from local industry.

Walt Cunningham, a gruff former astronaut and venture capitalist in Houston who is the architect of Houston’s second proposal, makes it clear that the current attempt has little in common with the first. The city’s pitch centers on space-based biotechnology and names as the managing consortium the Southwest Research Institute, the third-largest organization of its kind, with research grants and contracts totaling $140 million a year.

One of the most promising academic partners in the second proposal is the Bioprocessing Research Center at Houston. The center was organized during the first go-around; when that proposal went belly-up, the University of Texas Health Science Center decided to support the endeavor anyway. That was a wise move, since the center just signed a $2.4 million contract with NASA to support development of its own bioreactor-electrophoresis system to grow large quantities of pure culture mammalian cells. It will then sort valuable hormones out of the cellular soup by tagging their electrical charges.

“The system culls the few rare and precious molecules you want from a sea of junk,” explains Baldwin H. Tom, associate director of the bioprocessing center. For example, human kidney cells secrete small quantities of hormones that stimulate new cell growth in bone marrow and help dissolve blood clots. As pharmaceuticals, those types of hormones are almost priceless. Researchers at the center are working out a system whereby they would take a small square of living tissue from a human kidney, place it in a growth medium, and get the capsule into space, where enormous numbers of cells can be cultivated, free from the effects of gravity. Only in space can the huge number of pure culture cells be grown to make such enterprises economically feasible.

The bioprocessing center could have its bioreactor on-line in the next few years. But Tom says he hasn’t seen the necessary commitment from Houston’s business community. “We’re not going to be the next biotech center,” Tom says. “I laughed out loud when I heard [San Antonio mayor] Henry Cisneros talking about that. Where are the pharmaceutical companies? Where are genetic engineering companies?” There has been too much hype and not enough money. “It’s that simple,” he says. “It takes commitment. And don’t fool yourself. The other guys—in Philadelphia, Boston, Southern California—they’re not waiting around for us.” Nor are the French, the Germans, the Japanese, the Chinese, or the Russians, whose subsidized space programs continue to gather momentum, surpassing even NASA in several areas. The Japanese, in particular, are working toward commercial applications in space, including their own space manufacturing plant.

The amount of financial support from Houston’s business community will determine whether Houston will be the next center for commercialized space. By the time the city’s second pitch was submitted to NASA in April, Cunningham had signed ten industrial partners, whose contributions for the first year will total more than $1 million in money and equipment. The members include such heavyweights as Shell and Rockwell, in addition to Granada Corporation, a Houston-based biotech company. And at least five smaller companies are willing to put up about $5000 a year to peer through the consortium’s research window. Though none of the industrial partners has generated projects for the first year, Cunningham says they will design subsequent research. Houston’s bid is in the running with those of 25 other cities. “Our proposal is not in the bag,” Cunningham cautions. NASA will make its selection in August.

Vaucher from the Center for Space Policy places Houston among the top five U.S. cities in terms of space commercialization, in the pack with Los Angeles; Boston; Orlando, Florida; and Huntsville, Alabama. He agrees that Houston’s greatest strength is the engineering expertise pouring out of the Johnson Space Center, followed by the financial pool created by a legacy of oil. But Houston’s drawbacks are substantial: few high-technology companies are operating in town, and the defense and aerospace industries have offered little commitment to Houston.

A true believer like Agosto acknowledges those drawbacks with a wave of his hand. Like his fellow visionaries, Agosto hasn’t nailed down all the details of his elaborate schemes, and he doesn’t expect Houston to have all the solutions hammered out yet, either. “The industry is in its infancy,” he says. “The companies that will become the next huge international conglomerates haven’t even been started yet. But no one denies that space is the final frontier. It’s all up there. It’s all going to happen, and happen much sooner than anyone realizes.”

Ask him how he plans to make cement on the moon, a lifeless satellite that lacks readily available hydrogen and oxygen, not to mention water, and he says, “Don’t you see? It’s really quite simple.” Oxygen is easily extracted from ilmenite, an iron ore plentiful on the lunar surface, he explains. There’s reason to think hydrogen is there too, deposited in the lunar soil by solar winds. “And as I’m sure you know, you get your hydrogen and oxygen together”—Agosto smiles, the molecular matchmaker—“and presto! There’s your water.”

What possible use could old-fashioned cement have in space? Agosto is glad you asked. Lunar cement would be an effective radiation shield and an efficient thermal insulator, and it could serve as hardy protection against showers of micrometeorites. Mix cement with industrial byproducts in space, and it’s good for stabilizing hazardous garbage. Pluck some feral debris out of orbit (five thousand pieces of junk at last count), and use the burned-out satellite parts as aggregate filler to make cement’s sturdier cousin, concrete.

“Some people think I’m absolutely nuts,” Agosto says. “Cement in space? Am I out of my mind? I have to sell the idea every time I talk about it, but that’s okay. Once I explain to people that it’s really much, much cheaper to get cement into orbit from the moon than from the earth—because the moon’s gravity is one sixth that of the earth’s—people start to pay better attention.”

A visitor to the headquarters of Lunar Industries leaves Agosto’s apartment a little dazed but excited by his glimpse at the new economy, as dangerous as it is romantic. The explosion of the Challenger has demonstrated to the nation, especially to Houston and Clear Lake, that it will take more than marketing schemes to exploit the heavens. Still, when the visitor drives back to Houston along the Gulf Freeway at night, it’s hard to look at the full moon and not think of William N. Agosto—dreamer, engineer, hustler, mogul of nonterrestrial building materials—mixing up a batch of his crazy cement on the floor of the Sea of Tranquility.

William Booth, a writer who lives in Austin, has recently been awarded a Bush Fellowship from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Space

- Longreads

- Houston