I had intended to write this month about Norma McCorvey, a.k.a. Jane Roe, of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court case that decided a woman has the right to choose to terminate a pregnancy. But I got sidetracked by my own ambivalence: I knew that I was pro-choice, but I realized that I had never thought my position through. Perhaps, instead of profiling the 57-year-old McCorvey, who famously switched sides in the abortion war nine years ago, I might just talk to her, in hopes of learning to better articulate my own views. But when I first spoke with her by telephone in September, she interrupted me to ask, “Are you a believer?” I told her that I was a pro-choice Christian. “How can you be a Christian and pro-choice?” she demanded.

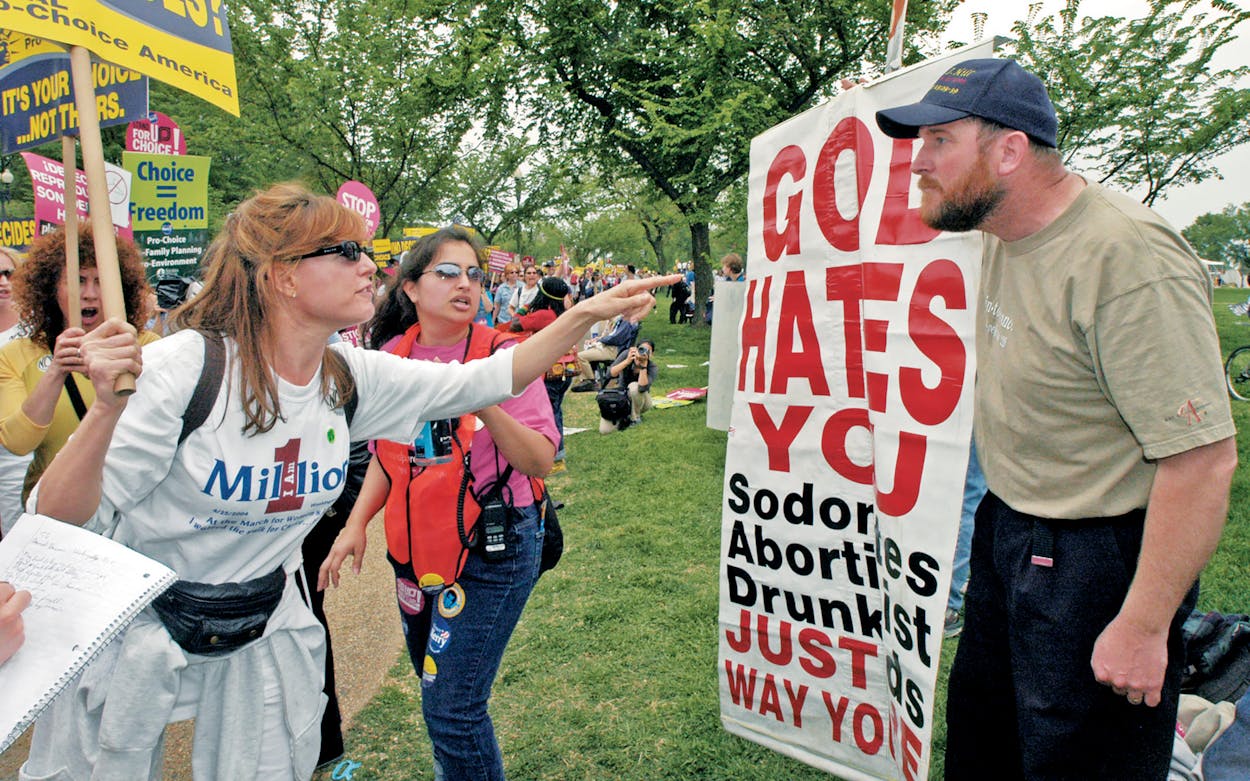

Okay, fair question. For the next few weeks, I set out to explore my beliefs. I read everything I could find on the subject and had dozens of conversations with people of all persuasions. What I discovered came as no surprise: The uproar of the true believers drowns out the moderate majority. Robert Baird, the chair of the Department of Philosophy at Baylor University, told me that if there was a spectrum of positions—with the extreme right advocating no abortions under any circumstances and the extreme left calling for abortions anytime a woman chooses, and for any reason—99 percent of us would find ourselves somewhere in between. “This is a moral issue,” he said. “When you begin identifying moral justifications—abortion to save a woman’s life or for rape or incest or for a thirteen-year-old girl who is clueless—the more reasons you find, the more you move to the left. The real debate hasn’t yet been properly framed: What should count as a morally justifiable position?”

My search for an answer to Baird’s question led me back to McCorvey. We met in San Antonio at a rally of true believers, a fundraiser for the Texas Justice Foundation, whose main mission is to overturn Roe v. Wade. McCorvey is a small, feisty woman with close-cropped hair and a viper’s tongue, and she moved inconspicuously among the pageantry of praying and patriotism and firebrand oratory. She is not what you would call an articulate defender of the pro-life position; she is driven not by ideology but by gut instinct. I liked her. She played the street tough but didn’t try to hide her soft side. She flipped open the screen of her cell phone to show me a photograph of her granddaughter, born to the first of three children she bore and gave up for adoption or to relatives. When we parted, she gave me a small gift, an ornament that contained a single mustard seed. “Jesus said that with faith no bigger than this mustard seed, you can do great things,” she reminded me.

I couldn’t determine whether the people at this rally loved or merely tolerated her: Though she and her longtime partner, Connie Gonzales, have renounced lesbianism, they continue to live together, an arrangement that can’t be comfortable to true believers. At the same time, she is vital to their cause. In June 2003 she went back to federal district court in Dallas, where Roe v. Wade was originally filed, asking that the decision be reconsidered. Only the original plaintiff or defendant can do this. Judge David Godbey denied McCorvey’s motion, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit likewise rejected her request. Now she is hoping to have her case heard by the Supreme Court. Having once been accused by the pro-life movement of murdering 35 million babies, McCorvey is now its standard-bearer. I wondered if she recognized the bewildering complexity of a conflict in which both sides had made her their poster girl.

The following day, over a riverside lunch outside her hotel, I read her two quotes from interviews she had given over a wide span of her life: “When you were a celebrity in the pro-choice movement, you told a reporter, ‘This issue is the only thing I live for. I live, eat, breathe, and think . . . about abortion.’ Now that you’re a star of the religious right, you say, ‘I’m one hundred percent sold out to Jesus and one hundred percent pro-life . . . No exceptions. No compromise.’ It seems to me that these two extreme points of view spotlight the enormous divide that is tearing our country apart. Is there no common ground?”

“No,” she said bluntly. “Not when human life is concerned.”

“When do you think life begins?”

She told me a story. Back in the mid-nineties, when she was working for an abortion clinic in Dallas and doing daily battle with the clinic’s next-door neighbor, the militantly anti-abortion Operation Rescue, she was cavalier about fetuses: “I’d call next door and say, ‘We’re barbecuing some babies for lunch. Why don’t you come over?’” Then one day she saw a fetal development chart and—bingo!—it became clear to her: Life begins at conception. “Then I started remembering all the dead children I’d seen, little arms, little legs,” she said, biting her lip. “We had to count them to make sure the abortionist got them all out of the womb. Then we stuffed them in freezer jars, six or seven to a jar. We had no sense of reality about what we were doing.”

“What I don’t understand,” I told her, “is why people who love fetuses so dearly seem mostly indifferent to children after they’re born.” I mentioned in particular the 1.4 million children in Texas who have no health insurance, to the apparent unconcern of the religious right.

“That’s not the problem of the pro-life movement,” McCorvey said. “I’m a grown woman and I don’t have health insurance. We are fighting for the unborn.”

But what about the rights of the mother? “Do the unborn have more right to life than the born?” I asked.

“Yeah,” she shot back.

The nut of the issue—when does life begin?—is also the point where faith and science diverge, or get intentionally mangled. McCorvey’s attorney, Allan Parker, the founder and president of the Justice Foundation, explained his belief this way: “You’re human . . . when you have forty-six chromosomes, because unless your life is interrupted, you’re going to develop and die the same way as every other member of the human species does.” One of the arguments that Parker will take to the Supreme Court is that, in the time since the original Roe justices considered this case, “vast scientific evidence [has emerged that] conclusively [proves] that life begins at fertilization.” What is this vast evidence? He cited such things as cloning and DNA. “If you send two samples of DNA to a lab,” Parker told me, “one from the mother and one from the fetus, they will tell you the samples come from two separate people.” Does that make a fetus a person? I put that proposition to Robert McFarlane, a Palestine cardiologist and a good friend of mine. McFarlane told me, “The chemical reaction that is life clearly begins at conception, but when those dividing, moiling cells become a person depends on what you define as a person.” Is it logical to define these cells as a person, thereby giving them greater rights than the woman in whose body they are situated? I don’t think so.

None of us have a hotline to God. The Holy Scriptures are filled with messages that advocate respect for the woman and the child, but there are no specific commands in the Bible about abortion. Jewish tradition teaches that life begins when the baby’s head emerges from the mother. “The life of the mother is our top priority,” explained Cantor Jaime Shpall, co-clergy of Congregation Beth Israel, in Austin. “Anything that jeopardizes the physical or emotional health of the mother must be put aside.” The mother’s health is also the primary concern of groups like Planned Parenthood, which prefer prevention of pregnancy to abortion.

The case against abortion is absolute; the case for choice is relative. “Life is messy,” explained the Reverend Kathleen Ellis, of Austin’s Live Oak Unitarian Universalist Church, who serves on the local Planned Parenthood advisory council. “We can’t always find one rule that fits every situation.” The Reverend San Williams, a pastor at University Presbyterian, in Austin, my spiritual home, told me about his attending the Presbyterian General Assembly in 1989 and listening to Mother Teresa. “She was so passionate, talking about the least among us, which obviously includes the unborn,” Williams told me. “My conscience was moved by her words. At the same time, I was on the Planned Parenthood board in Corpus Christi. Abortion is an agonizing choice.” The Presbyterian Church (USA) believes that abortion is the “ethical decision of the patient . . . and therefore should not be restricted by law.” Talking with these clergy members, I discovered the answer to McCorvey’s question: How can one be a Christian and still be pro-choice? By recognizing that life is indeed messy. A Christian doesn’t have to view every moral decision as determined by God’s word or even the word of church hierarchy. We are individuals who are created by God with the ability to make ethical decisions based on our own personal beliefs and experiences, within the framework of Christianity. In the event Scripture has not specifically spoken—and I believe abortion is such a case—it is wrong to speak in moral absolutes.

But it is also wrong to refuse to acknowledge the moral force of the pro-life argument. Several pro-choice friends have talked about how their faith in their stand was shaken when they saw sonograms of their own developing child. “When you see little arms and legs moving, you know it’s a tiny human,” one friend said. Jan Williams, the wife of my pastor, made a similar observation. “I don’t believe that a cluster of cells is a person,” she said. “But you have to start this discussion with the admission that you are killing something.” Baird, the Baylor philosophy chair, told me, “I find every abortion tragic. At the same time, I think there are times when it’s morally permissible. I object to any repeal of Roe v. Wade. I think we need to leave that option open.” I agree: Sometimes abortion is the best of bad alternatives.

So what to do? For starters, the moderates have to reframe the abortion debate. They should start by affirming the moral seriousness of the pro-life position, even while holding fast to their belief that there are situations where abortion is morally justifiable, ranging from rape, incest, and life-threatening pregnancies to teenage flings and middle-age mistakes where women never intended to get pregnant and can’t emotionally or physically handle parenthood. Pro-life advocates who say they love fetuses should care about the prevention of pregnancies as well as their termination and about children as well as fetuses.

The right-to-life movement is so certain that life begins with fertilization—and that its conclusion forecloses all other discussion—that it feels entitled to force its belief on the rest of us, not only through the church but also through the political system. Two new laws backed by the pro-life movement were passed by the Texas Legislature in 2003. One makes it a crime to kill a fetus in the course of harming a pregnant woman; although it specifically exempts abortion, the law states that a fertilized egg is “an individual,” thereby throwing the weight of the state behind the idea that a fetus has legally enforceable rights. Another bill makes having an abortion more difficult by imposing such requirements on abortion clinics as a 24-hour waiting period, parental consent for minors, and informing patients that they have the right to view photographs of dead fetuses. Pro-choice advocates vigorously oppose these restrictions, perhaps too vigorously. The weakness of the pro-choice side is that it risks coming across as pro-abortion rather than pro-choice. I believe that the avoidance of abortion is a legitimate goal, that if a woman who has had to go through these state-mandated obstacles changes her mind and decides to carry the baby to term, everyone wins. Abortion should always be the last choice. At the same time, those who are dead set against abortion should stop opposing birth control, sex education, and other things that help prevent pregnancies. Nobody is really for abortion, but unless people stop having sex, it’s here to stay.

I thank Norma McCorvey for making me explore my own beliefs and for helping me understand and respect her position on abortion. But ultimately, I agree with Robert Baird and Jan Williams and with the teachings of my church: Abortion has to be a woman’s choice. Regardless of what happens to Roe v. Wade, that should be the law, and from it moderation should flow.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Abortion