When my grandfather retired from Armour & Company twenty years ago, he and my grandmother moved to Houston from Kansas City so that they could be near their only son. But, as is so often the case these days, the family didn’t stay put. My sister headed for Minnesota, my brother for Alaska, and then my father was transferred to Salt Lake City. My parents bought a big house in Utah and remodeled the lower level with the idea that Grandpa and Grandma might eventually want to join them. But they said no thanks. They liked the mild Texas winters and didn’t intend to do any more moving.

So, it’s only my grandparents and I in Texas now. They are well into their eighties and still chugging along quite independently, living in their own home, driving a 1965 Mercury with 50,000 miles on it, regularly attending the XYZ (Xtra Years of Zest) Club and other church functions.

Grandma still sews, although she is blind in one eye, and cooks three meals a day, despite her painful arthritis. In perfectly good cheer, she likes to recite a piece of doggerel entitled “My Get- Up-and-Go Has Got Up and Went.” Still, she hints from time to time that she has earned the right to retire after 64 years of heavy housework. She would prefer to live at one of the posh retirement homes that cater to the generally healthy elderly but also provide nursing care should it be needed. She coaxed Grandpa into visiting one of them last year. He got as far as the main lounge, plonked himself down in a comfortable chair, and announced, “I’ve had it.” He explained to me later, “I wouldn’t want to live there. You wouldn’t have any work to do, any groceries to shop for. You’d just be waiting for your meals.” So much for moving Grandpa into a retirement home. But Grandma says, “If anything ever happened to him, I’d hightail it out to that home just as fast as my legs would carry me.”

The family has had those “if anything ever happened” discussions from time to time, but we’ve never really faced up to the question of what to do if one or both of the grandparents become seriously incapacitated. It is reassuring to note that most of the elderly in this country function reasonably well into their eighth and even ninth decades. The majority live out their lives independently in their own homes. Most of those who are in nursing homes have frequent contact with family members or close friends. Contrary to the cruel myth we assign ourselves, we are not neglecting the aged. In fact, we often maintain them in our or their homes long past the point when we can give them adequate care. But there comes a time when the very old need nursing care, care which very few of us can afford except through a nursing home.

Unfortunately, for most of the elderly in Texas, there are only three alternatives: living alone, living with family, or living in a nursing home. There are currently 80,000 patients in Texas nursing homes, or, as the industry prefers to call them, “long-term healthcare facilities.” The residents, on the average, are older, sicker, and poorer than their counterparts in the com- munity. Medicaid, the federal-state medical assistance program for the indigent, pays about 60 per cent of the nursing home bills in Texas. Medicare, the federal health insurance program for the elderly, will assume the bill for up to one hundred days of skilled nursing home care after hospitalization, but this accounts for only 3 per cent of the nursing home tab in Texas.

Seventy per cent of the nursing home residents are women, primarily widows. Statistics show that women outlive men in every part of the developed world. Minorities are underrepresented in nursing homes because of differences in culture (Mexican Americans keep their old folks at home) and because the poor die younger.

Medical science has not made much progress in recent decades in treating infirmities of the aged. Even so, an unprecedented 75 per cent of the American population now reaches the timeworn marker of 65, primarily because of our success in reducing the death rate among children. Once the 65-year hurdle is cleared, a man can expect, on average, to live another 13.7 years, a woman 18 years. Unfortunately, very few live that long without developing chronic health problems. That’s why, for an American over the age of 65, the odds on spending time in a nursing home are one in five and rising.

We simply had not planned on so many people living so long. In addition, fewer and fewer families can care for their elderly in the family home because houses have gotten smaller and family members more mobile. Only the wealthiest families can afford household help, much less the services of a professional nurse. Women who once stayed home to care for both the young and the old are now working to help pay off the mortgage. So when grandfather has a massive stroke and needs physical therapy, needs to be fed and dressed and helped to the bathroom, the family begins the traumatic debate on whether they can care for him at home or whether they should send him to Siesta Manor or Autumn Leaves or Green Acres or Silent Night or Serenity Haven or Sunnyvale Manor or one of the other nursing homes, all of which seem to have nicey-nice names.

It is one of the most difficult and emotional decisions a family must face, and it isn’t at all true that keeping an elderly relative in your own home is always preferable to sending him to a nursing home. Sometimes, society being as mobile as it is, keeping a relative would mean moving him from the area where he’s lived for years, away from friends and familiar surroundings. Sometimes the relative is simply too infirm and needs the kind of care that a nonprofessional, no matter how loving, cannot provide. Sometimes there is a personality conflict between the old person and a child or spouse, which means that resentments will fester on both sides when the two people are forced to live close together, and which benefits no one. And sometimes there simply isn’t enough room or there are too many steps or something else about the house itself that makes it unsuitable for the aged.

Even after deciding that a nursing home is the only choice, family members not only have to bear the painful realization that they cannot personally care for their elderly relation, but they must also confront the nagging fear that they are dumping their relative into the kind of institution so often in the news—the one with unhealthy conditions or with attendants who are negligent or abusive. But, after touring a variety of nursing homes in the state, I am convinced that, with a little common sense and a few basic guidelines (which we will come to later), a family can easily avoid the bad homes (some of which we will also mention). Even more encouraging, the very best homes are not that difficult to recognize.

Golden Acres, the nonprofit Dallas home for the Jewish aged, is run by a nationally recognized authority on care for the elderly, Dr. Herbert Shore. He refers to his operation as “a campus for the aged.”

Golden Acres has 180 patients and 160 full-time and 24 part-time employees, which is a much more favorable staff-to-patient ratio than is found in profit-making nursing homes. In addition to a roster of qualified nurses, Golden Acres has the services of a psychiatrist, a podiatrist, a dentist, a pharmacist, three registered occupational therapists, a physical therapist, a dietician, a recreational therapist, and social workers. Although few pay the full rate, the cost per patient comes to about $32 a day. That’s actually just for board and utilities and nursing care and other services. It doesn’t include the cost of the buildings, which would be figured into the daily charges of a proprietary home. The Dallas Jewish community raised the money for the buildings at Golden Acres and makes up a yearly operating deficit of $300,000.

“I could fill this place with Whistler’s Mother, sweet little old ladies, and no one would ever know the difference,” Shore says. Instead he takes on many hard cases that other homes can’t or won’t handle, including patients with severe physical and mental impairments.

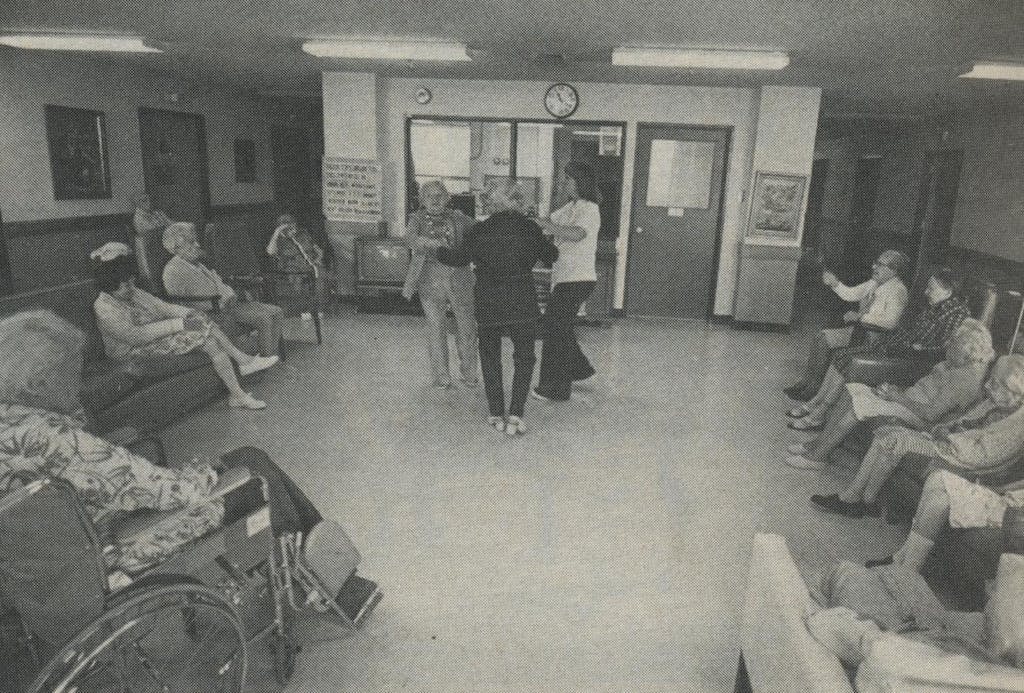

Like all good nursing homes, Golden Acres has a monthly calendar bulging with activities, some with a distinctly intellectual cast. In addition to the bingo games and the monthly birthday party for residents, Golden Acres promotes poetry readings, book reviews, a spelling bee, a quiz show, art appreciation, conversational Yiddish, holiday celebrations, and—a nice touch— happy hour with an open bar and old recordings by the likes of Sophie Tucker and A1 Jolson.

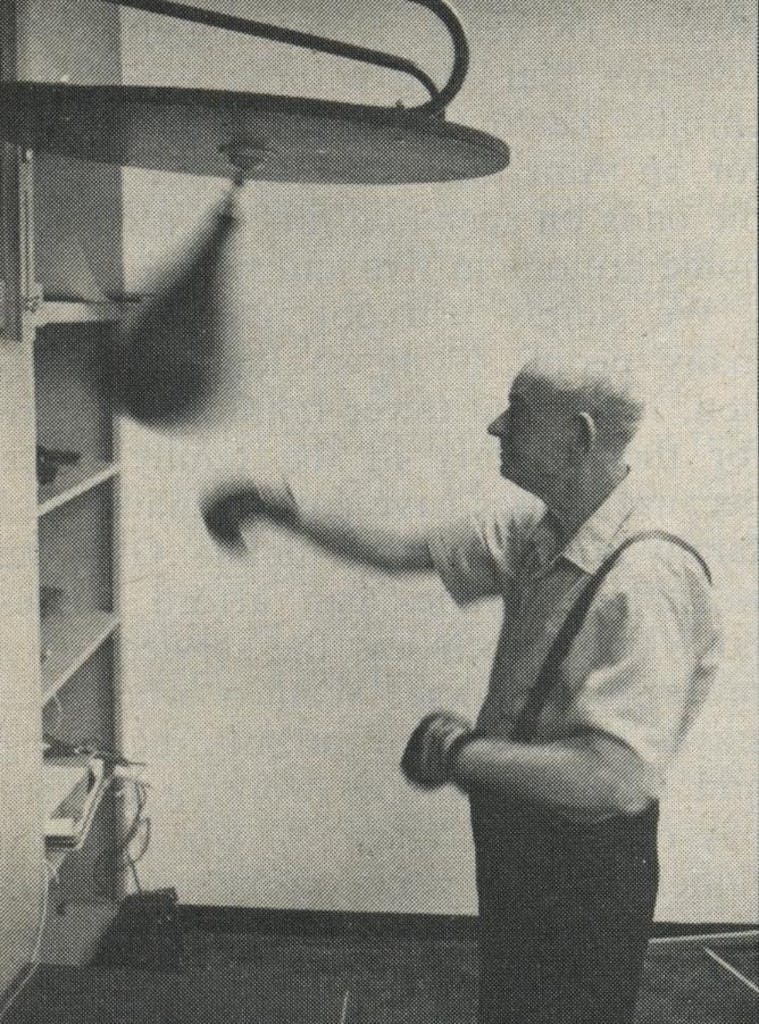

The Dallas home also has extensive craft and hobby activities, which serve as occupational therapy for residents. People are gardening, hooking rugs, working wood, and doing something called liquid embroidery. Golden Acres even has a sheltered workshop license from the Department of Labor so that residents can earn money tagging jewelry. My initial reaction was to wonder whether the old and tired and crippled shouldn’t rate an exemption from painting ceramic swans and attending current-events club meetings. I soon learned, however, that there is sound theory behind this everybody-out-for-volleyball approach. Gerontologists believe that old folks must make use of their mental and physical abilities or lose them. The aging process isn’t a straight downhill slide; it’s a series of ups and downs. Skills once lost can be regained, at least for a time, and new skills can be learned.

“Working here, you have to redefine success—it may be just holding your own or slowing the rate of decline,” explained Natalie Beers, whose specialty is recreational therapy. Beers runs Byer Activity Center, which is Golden Acres’ combination club, kosher dining hall, and therapy center for the people who live in the Golden Acres retirement apartments and the elderly from the surrounding community. About 25 people who live in the neighborhood come to Byer Center on weekdays for what Beers prefers to call “day service” rather than day care. Still, it’s tempting to make comparisons with classes for preschoolers—the same hot lunches and late-afternoon snacks, organized crafts and games, even a room set aside for people who want to take naps.

“Often people who come to Byer for day service have withdrawn. They’ve lost the social skills they once had. The line of least resistance for them is to draw further and further into their shells. So we try to create new jobs for some of them, hopefully using some of the roles they have used before. We want them to achieve something and feel they belong,” Beers explained.

Take, for example, Carl Johnson, a 75-year-old retired accountant with Parkinson’s disease. He lives in North Dallas with his sixty-year-old wife, who works and is unable to care for her husband during the day. When his wife is gone, he is a virtual prisoner in his own home (lack of transportation is one of the major obstacles to independence among the aged). Johnson needs assistance in walking, and he has fallen at home a number of times, where he had to lie floundering like a fish out of water until his wife returned to rescue him. Since he can’t fix his own meals, he often wouldn’t eat during the day.

Johnson had been an active man and a fine amateur painter, but he had become bored and lethargic at home. His mental condition was taking a distinct turn for the worse when a social worker referred him to Golden Acres. A van now picks him up daily and delivers him to Byer Center by 10 a.m. He has physical therapy to help him with his walking, participates in the mild exercise program offered twice a week, gets his blood pressure taken and his medication supervised. “I wanted to rekindle some of his earlier interests,” Beers said. “He can’t paint any longer, but now he’s teaching a class in oil painting and is learning to do macramé, copper tooling, and ceramics, all crafts that he can still handle. He’s a lot better off than he was at home alone.”

Day services for the elderly are still in the experimental stage in this country. With an eye to keeping people in their own homes as long as possible, the federal government has funded a few day programs around the country. So far the economic news is not good. Byer Center charges only $7.50 a day plus $1.50 for transportation, but the actual cost of the program is more like $16 a day per person. Skilled nursing and therapy programs—actually day hospitals—cost up to $60 or $70 a day in some urban areas.

Other government services are available in some parts of the state, primarily for the poor. Federal funds send lawyers, nurses, and trained homemakers into the homes of the elderly. Some receive home-delivered meals and door- to-door transportation services. There are even a few foster homes for the aged. But, because of limited funding, these programs reach only a small percentage of the people who need them. “The aged get the short end of the stick. They always will, unless we can redirect present thinking away from medically intensive services into more appropriate social services,” Dr. Shore insists. Of course, it’s easier to persuade taxpayers to fund programs for children than programs for the elderly, whose best years are behind them. But Shore argues, “People have a right to a full life, all of life. Too often I’ve seen society give up on people who still have productive and creative years ahead of them.”

At Golden Acres, the staff doesn’t give up on anyone, not even those who a few years ago would have been regarded as hopelessly senile. One of the stranger therapy sessions I attended was reality orientation, or, as the patients call it, “memory class.” It is designed to help confused people fix themselves in time and place. Thirty minutes a day, five days a week, the participants are wheeled into class and drilled on the date, temperature, upcoming holidays, all the common currency of daily living. Speaking in a very loud voice for the benefit of the hard of hearing, the nurse bombards them with questions: “Today is Tuesday. What is tomorrow? What color is my dress?” The key to the program is repetition. Shore explained that, in addition to helping patients keep some grip on a floating, shifting sense of reality, memory class is worthwhile because it encourages staff members to talk with the hard cases who might otherwise be ignored.

Touring the two nursing wings devoted to the mentally impaired was by far the most disturbing part of my visit to Golden Acres. Director of Nursing Muriel Browning moved me briskly along with the crisp compassion of someone who has seen such sad cases too many times before. The patients sat like zombies in the dayroom watching the shifting colors on the television set. One fellow shuffled down the hallway reciting numbers, “Zero-eight, zero-nine, zero-seventeen. I’ll be dead pretty soon.”

“If you don’t have enough personnel, you medicate them,” the nurse said. “I have a hundred and five people and sometimes I feel understaffed.”

Gerontologists now shun the term “senility,” preferring when possible to put a more precise name to the mental problems of the aged. Sometimes disorientation and short-term loss of memory are the results of institutionalization. Patients returning from a long bout in the hospital are frequently confused, but many of them can regain their former mental acuity. Other patients, however, suffer from organic brain impairments, which cause anxiety, paranoia, depression, childishness, and a gamut of other symptoms that are difficult to diagnose. The damage can be caused by anemia, infection, malnutrition, drugs, alcohol, or cerebral arteriosclerosis, which hardens the brain’s blood vessels and reduces its oxygen supply. In some cases the damage is reversible and in some it’s not. On top of these problems, a disproportionate number of old people suffer from depression and other functional mental disorders for which no physical cause has yet been found. The traumas of aging, pain, poverty, isolation, reduced social status, boredom, and loneliness take their toll.

It was a haunting experience, seeing what’s in store for the long-lived. The most vivid image I took with me from Golden Acres was of a group of patients tottering, shuffling, and rolling slowly down a well-polished hallway like a band of lethargic crustaceans. They moved ever so carefully with the aid of clanking aluminum walkers, crutches, and canes, with palsied hands laboring to propel wheelchairs. I had to keep reminding myself that these were the fortunate ones, the people getting the best care available.

Margaret Maxwell and her husband live in a home whose services and facilities are much more typical. Together they pay $42 a day for a small two-bed room in a corporately owned intermediate-care home (24- hour-a-day care with a registered nurse on duty only during the day shifts). Skilled nursing (a registered nurse on all shifts) costs a few dollars more a day. The Maxwells receive three uninspired but nutritious meals a day, medication at proper intervals, clean linens, and church services on Sunday. Their nursing home is reasonably clean, and the administrator is a relentlessly cheerful lady who breathes considerable life into the surroundings. The home is neither a firetrap nor a health hazard. The patients are neither neglected nor abused, but it is a dreary, closed-in atmosphere nonetheless.

When I asked Mrs. Maxwell to describe her life, it was as if she had been waiting months to answer that question: “I dreaded coming to a nursing home,” she said. “I only came because my son the doctor wanted me to. The whole thing was frightening. You heard people crying in the night. One of them would make a growling noise like a dog. And some of the senile ones, they have to be tied down. We’ve had our tragedies that don’t appear in the paper. We lost one man. He wandered away and a child found his body eight days later. So now, when we see someone who has no right to be out in the drive, we all sound the alarm.

“It’s hard to adjust. I was a dignified grown person and I couldn’t get used to being treated like a child. And the food, well, you never get adjusted to that. They feed you what they think is good for you, but it’s never like what you’d fix for yourself. For a while the roaches were so bad that we couldn’t keep food in the room, but they’ve fumigated and now it’s better.

“My husband has cancer. He and I don’t associate with the others much. So many of them are only half there. I gave the little thing down the hall a cookie one day and then she wanted a cookie every day. She just haunted me. We all love the patio and the lounge, but there are never enough chairs and there’s fussing over who gets them. I don’t play bingo either, because the big ones push you out of the way and grab all the best cards. You have to learn to watch out for yourself. There’s a cute little lady who lives down our hall. She was walking by and gave me a whack. Why, it almost threw me down. So I hit her back.

“Some of the aides, the ones who have been here a long time, are very nice. When I fell down and hit my head in the bathroom, an aide picked me up off the floor. She got me to the hospital just as quick as you please. And when I had my cataract operation, the staff gave me the feeling that I could try again. The woman right across the hall is an inspiration to us all. She has only one leg and terrible, terrible rheumatoid arthritis, but every day she gets up and puts on her makeup and sits in the lobby. You know, there’s always a smile on her face.

“I thought I would never get adjusted but, after three years, I have. My husband and I have a pleasant place to sit here. The view is wonderful. When the room closes in on me, I take my walker and walk just as far as I can. Sometimes there’s nothing to do but laugh. Someone asked me one day, ‘What are you in for?’ I told her, ‘I think I’m in for life, honey.’ ”

Mrs. Maxwell lives in one of the profit-making homes, which offer the advantage of not requiring a particular religious background, but which also have disadvantages—most stemming from the difficulty in balancing proper care against an income statement. The largest chain of nursing homes in the state is National Living Centers, which has 92 homes in Texas. Both NLC and Retama Manor, the third-largest chain, are subsidiaries of ARA Services (the initials don’t stand for anything; they’re just initials), a diversified holding company which is also involved in food-vending machines, school bus service, and periodical distribution. While many singly owned homes are going out of business, NLC is still growing, a fact that leads one to presume that the corporation is making a sturdy profit. No specific figures are available on NLC, but the State Department of Health reports that the average profit for proprietary homes in Texas is 7.9 per cent, compared to a 1.8 per cent loss for nonproprietary homes. Proprietary homes spend an average of $4 a day less on patients than their nonprofit counterparts. In some facilities this saving might be attributable to good management and economy of scale, but in most it is probably basic penny pinching. Corporate homes are run more like a business than a service. Even the best have what Herb Shore would consider skeleton staffs.

NLC and Retama Manor nursing homes have run afoul of the regulatory process more often than most other facilities. According to the Department of Human Resources, both exceed the state averages on Medicaid contract cancellations and vendor holds, the latter a punitive procedure in which the health department recommends to Washington that Medicaid funds be withheld until a home’s deficiencies are corrected. Perhaps that’s why NLC regional vice president Erling D. Benson chimed such a defensive note in our interview. It was an unhappy day for Benson. He had just received word of his father’s death after a long joust with cancer. Despite the fact that he had to make funeral arrangements and catch a plane that afternoon, Benson kept our appointment. Nursing home executives don’t have very many opportunities to tell their side of the story.

Wearing a bright orange sport coat in 100-degree heat, he drove me to two of NLC’s homes among the pine trees in Houston’s Memorial district. As he roamed the halls keeping an eye peeled for burned-out light bulbs and empty towel dispensers, the youngish, portly executive enumerated the woes of the nursing home business.

“The general public does not associate with a nursing home until there is a crisis, and then they are exceedingly demanding. They have some guilt, because they’ve had to admit that they can’t take care of father or mother any longer. Part of their faultfinding with us is an attempt to justify their own guilt. Approximately 90 per cent of our patients come from a hospital setting, where the average cost of care is $125 to $200 a day. Now, families just can’t expect that same level of care at a nursing home. As long as the family isn’t here, the patient is just fine, but as soon as the family comes in, the food is terrible, everything is terrible. You’d be amazed how many parents try to promote guilt in their children. Actually, most of our families are supportive, but some of them just don’t care. We had a Father’s Day program at one of our homes and invited all the sons to the party. Not a single son came, not a single son.”

Benson noticed a fresh urine puddle on the linoleum where a patient had parked his wheelchair in the hall. “Nurse, we’ve had an accident here,” he called. An aide appeared promptly with a mop. We proceeded toward the lounge area where a dozen patients were grouped around a TV, not so much watching the tube as absorbing its sound and color and motion.

My guide continued, “The regulatory agencies want us to put our patients in such a protected environment that they lose their dignity. There is a regulation for every aspect of living—you have to document everything in the chart. Can you imagine a man who’s been shaving himself daily for sixty years who is told he can’t use a straight razor any longer because a patient can’t have hazardous materials in his room? Or a lady being told she will not be able to keep knitting needles in her own possession? Or being allowed to have only round-point scissors like kindergarten children use? Smoking can be done only in supervised areas, like out in the hall next to the nurse’s station. That’s reasonable, because fires are a terrible problem in nursing homes. Some of the patients are like little children and try to sneak a smoke in bed in the middle of the night. And we have problems with families who bring in cigarettes and lighter fluid. What are we going to do? Frisk everyone who comes in here?”

We stopped by the administrator’s office for coffee and angel food cake and the subject changed to Medicare, the federal health insurance program which pays for up to a hundred days of nursing home care after hospitalization.

“Medicare is unbelievable,” Benson said. “Sometimes it takes three months for reimbursement and often the feds say your patient wasn’t sick enough to warrant convalescent care, so we’re not going to pay you. A patient almost has to have a stroke or a brand-new head fracture to be covered. It becomes a guessing game for the administrator, trying to predict whether a patient is eligible for Medicare. Why, these elderly folks need a Philadelphia lawyer to keep up with the regulations.”

For all his frustration with the rules, Benson conceded that government regulation is necessary. “In any industry there’s going to be some kind of abuse,” he said. “It would be helpful if the regulations had more practicality to them, more common sense.”

Later I talked with David Bragg, head of a nursing home task force in the Texas Attorney General’s Office, who agreed that many of the state and federal regulations miss the mark.

Bragg explained that the paperwork rarely tells the whole story. “For example,” he said, “we visited this beautiful home in Beaumont. It had no urine odor whatsoever [an easily detectable sign of poor maintenance]. While we were there, we had an opportunity to watch the staff respond to an emergency. A lady fell and immediately six or seven aides and nurses descended on her. They had the oxygen out; it was a smooth and efficient response. This place even had a petting room for amorous patients. The people who ran the home were concerned about the quality of the patient’s life as well as the quality of the nursing care, but the home happened to be on vendor hold because of charting problems. It was being punished for not keeping up with the paperwork.”

At the other extreme, Bragg said, was Forest Manor in black East Dallas, the first nursing home in the history of the state to be put into receivership (it is now under new ownership and has been relicensed). “Forest Manor was one of the worst hellholes we found, but it was in paper compliance with the regulations,” he said. When the AG’s investigators first visited Forest Manor they were appalled by the odor. Bragg said one of his staff later asked an auditor from the Health Resources Department why she hadn’t written about the odor in her report. “It’s not my job to smell,” she said.

Bragg maintains that top-level state health department officials act too often as industry consultants rather than as enforcers of the law. The AG’s Office has been much more willing to take action against allegedly substandard homes than has the health department, and the two agencies have clashed over policy during the past year.

Bragg’s task force became embroiled in gubernatorial politics when it sued a Dallas nursing home co-owned by Don Brewer, president of the American Health Care Association, and John Smith, vice president of the Texas Nursing Home Association. The TNHA, the lobbying group for proprietary homes, had endorsed Dolph Briscoe over Attorney General John Hill for the Democratic nomination for governor. The AG’s Office charged that the Dallas home was unsanitary and that it severely neglected patients. Brewer responded, “It’s extraordinary that the normal nursing home regulations work nicely except in an election year.” The suit is still pending.

The Attorney General’s Office started its investigation last year about the same time the Lufkin News reported an incident at a home in which a 76- year-old woman patient was beaten with coat hangers and belts by four nurse’s aides. When Lufkin reporters looked further, they discovered evidence that in area homes:

- one hundred people were fed with only seven chickens;

- a patient lost 25 pounds in two weeks because of what was described rather vaguely in the paperwork as “an error” by the nursing home staff;

- patients were tied down in their beds overnight;

- a double amputee was left alone in the dark in a whirlpool bath;

- a patient had bedsores so bad that they required skin grafts;

- and a patient went 24 hours without insulin injections or pain medication because of an unpaid pharmacy bill.

Bragg says that “homes in which abuse and neglect occur are a very small percentage.” Still, many people have horror stories to tell. While I was touring nursing homes in Dallas, I fell into conversation with a waitress at my motel restaurant who had worked for a short but traumatic time as a nursing home aide in her hometown in East Texas. She said she had some idea of how a good home should be run because as a child she had helped her grandmother, who owned a small nursing facility. When she went to work for this new nursing home, the only one in town, she was shocked to see comatose patients who didn’t get bathed or turned in bed and to find dirty needles left on bedside tables. If a patient was difficult to feed, the aides would simply leave his food to cool uneaten by his bed. “We had this one colored lady,” the waitress remembered. “She couldn’t talk or anything, but she’d shake her finger at you. So some of the kids who worked as aides would pull on her hair or pinch her. They liked to tease her. They were just high school kids, but I really got after them for their meanness.

“The reason I finally left was that I found this one lady in bed with a high fever. I went to the head nurse and told her about it. She said not to worry because the old woman ran a high fever all the time. Well, I went back in the lady’s room four or five times that evening to check on her. She was acting funny, having convulsions. I kept reporting back to the nurse, but she kept saying not to worry and, without even looking in on that old lady, she went on her supper break. That’s when I walked out. I just couldn’t take any more.”

The waitress poured me another cup of coffee. I sipped and she hovered as we both tried to imagine how perfectly average people could become so callous working in a nursing home. Our question was answered the next day by Donald Learner, administrator of a downtown Dallas retirement home and the man Attorney General John Hill appointed as receiver of Forest Manor.

“You have to remember that the wages paid in all nursing homes are rock bottom,” he said. “The benefits are next to nil, the work disagreeable. And the nursing profession, even in hospitals, tends to draw a certain percentage of people who want to have power over someone else. It’s a constant problem that administrators have to watch. Psychologically, the aide’s only defense in going back to the nursing home day after day to filth, disease, and death is to say, ‘I don’t care, I won’t care.’ Many people are going to die and the nurses and aides are going to see it. You’ve got to get a good grip on your sanity to stand it.”

Nursing home personnel take a tremendous amount of abuse from patients, who may be querulous, disoriented, and even violent. The majority of nurse’s aides in Texas are uneducated black women, many of whom must endure racial slurs as part of an already dismal job. A journalist told me about his grandfather who had always hated Negroes. When he had a stroke, he was sent to a nursing home where all of the aides were black. “They came in to change his bedclothes and he would kick at them and try to strike them. He just couldn’t handle the idea of being touched by blacks,” the journalist said. “I think it literally killed him. He died after only two months in that home.”

I know a young man who was an aide at a top-rated proprietary nursing home in El Paso a few years ago. He said he had to guard against getting depressed and irritable. “There was a man who acted like a bowl of Jell-O every time I tried to dress him; he wouldn’t cooperate. I’d find myself becoming forceful with him. I never hit him but I wanted to. I’m sure that if someone had sat me down and explained to me that the man had no family and had a painful, incurable disease that left him grumpy and daffy half the time, then I would have been more understanding, but we got no training at all. The staff was so slim that I felt rushed all the time. I certainly wasn’t giving good maintenance care. I could have spent all day just changing beds, and never have found the time to give bed baths or move someone from bed to chair and turn on his TV set. I know that the sheets often weren’t changed on the night shift.”

Bill Flanary, an assistant attorney general who has been making what the nursing home lobby has branded as improper “night raids” on facilities, says that some of the homes that look the best during the day are the opposite at night. “After eleven p.m. all the patients should be in bed. You walk into a dank, smelly atmosphere and hear people moaning and crying. I’ve found as many as sixteen incontinent patients lying in their own feces and urine. There will be only nine or ten sheets allotted for changing, and all the aides are asleep. Some aides let the patients lie in their own waste all night and then change the beds right at the end of their shift.”

To avoid leaving one of your relatives in such a place you should begin by getting a list of licensed facilities from the Social Security Administration district office, local and state offices of the Department of Human Resources, the Department of Health, or one of the other agencies that deal with the aged. Various agencies also supply brochures that explain the levels of care available, the costs of services, sources of government financial aid, and the legal requirements for each type of home. Some of the books include checklists to use when inspecting the homes, but the best resources you have are your own sight, smell, taste, and common sense.

Your first visit should be by appointment with the administrator. Get precise information on the room rates of the home and what services are not included in the basic rate. Typically, the extras are physician services, brand- name drugs and medications, physical therapy, and personal services such as hairdressing and telephone calls. There should be a written agreement regarding all financial transactions.

Talk with the head nurse and the activities director and see what other resource people are available. Unfortunately, most proprietary homes operate with a staff that is about 98 per cent unskilled. Often the only people with any professional training are the administrator, the assistant administrator (if there is one), and the nurses. At many homes, even the activities director is paid the minimum wage. A licensed facility is required to have at least one nurse per thirty patients per 24 hours, but the more favorable the nurse-to-patient ratio, the better the care.

On at least one visit you should eat a meal to see if the food is bearable and plentiful and if the people who need assistance while eating are getting it. Bill Flanary says that he has seen homes with food budgets as low as $1.25 a day per patient, and that included not only three meals and snacks but a patient’s share of household supplies and non-generic drugs as well.

Check out the odors. The home should be spotless. Do aides arrive quickly to clean an incontinent patient? Are the patients neat and active and alert or do they look overmedicated and neglected? Do they talk to you freely or does the staff seem to interfere? Are there many thefts? If a couple is moving into a home, make sure that they will be allowed to stay together. Sometimes this is impossible because they require different levels of care, but some homes segregate the sexes unnecessarily. Sometimes people are transferred from room to room and even home to home without adequate notice or explanation. It is terrifying for an old person to go to the dining room for a meal and return to find that he has been moved into a new wing and all of his possessions are in disarray.

Check to see if the lighting is adequate and if there are any hazards, like unsturdy chairs and things to trip over. Are there sufficient guardrails in the halls and grab bars in the bathrooms?

It is quite common for a young person to insist that he will not live to see old age. He prefers to imagine himself dying an untimely and dramatic death. Or, he says, if worse comes to worst, he will commit suicide rather than slide into decrepitude. Such are the fantasies of people who can’t bear the idea of having no control over their fate. But by the time we get there, I’m sure most of us will agree with Maurice Chevalier, who said that old age isn’t all that bad when you consider the alternative.

Of course, in researching this article, I saw many things that only intensified my mistrust of those who put too favorable a light on old age. A certain amount of despondency—among young people contemplating the future and among the aged themselves—is only reasonable. Still, when I think of old people I admire, they are always the ones who keep on going despite the pain and loss and bad living conditions. I think of a black woman in a Dallas high rise who says she gets off her rocker every Thursday and lopes over to a North Dallas church to work with the children of the rich. I think of a 98- year-old dowager in a Stephenville nursing home who is still doing political organization despite her complaints that fellow patients “forget what you tell them by the time they get to the end of the hall.” I think of my own grandmother who, at 83, still has enough zing in her to get on a plane by herself and fly to Kansas City for a family reunion—of her in-laws. I only hope that in the future this country will be willing to devote more resources to giving the elderly an opportunity to keep on living and doing right up to the point when they’re all lived out.

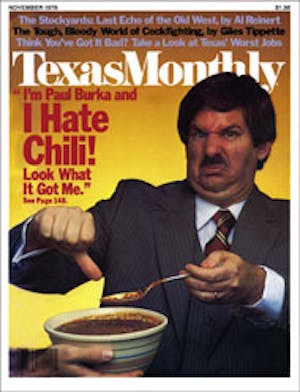

“Gay Nineties”

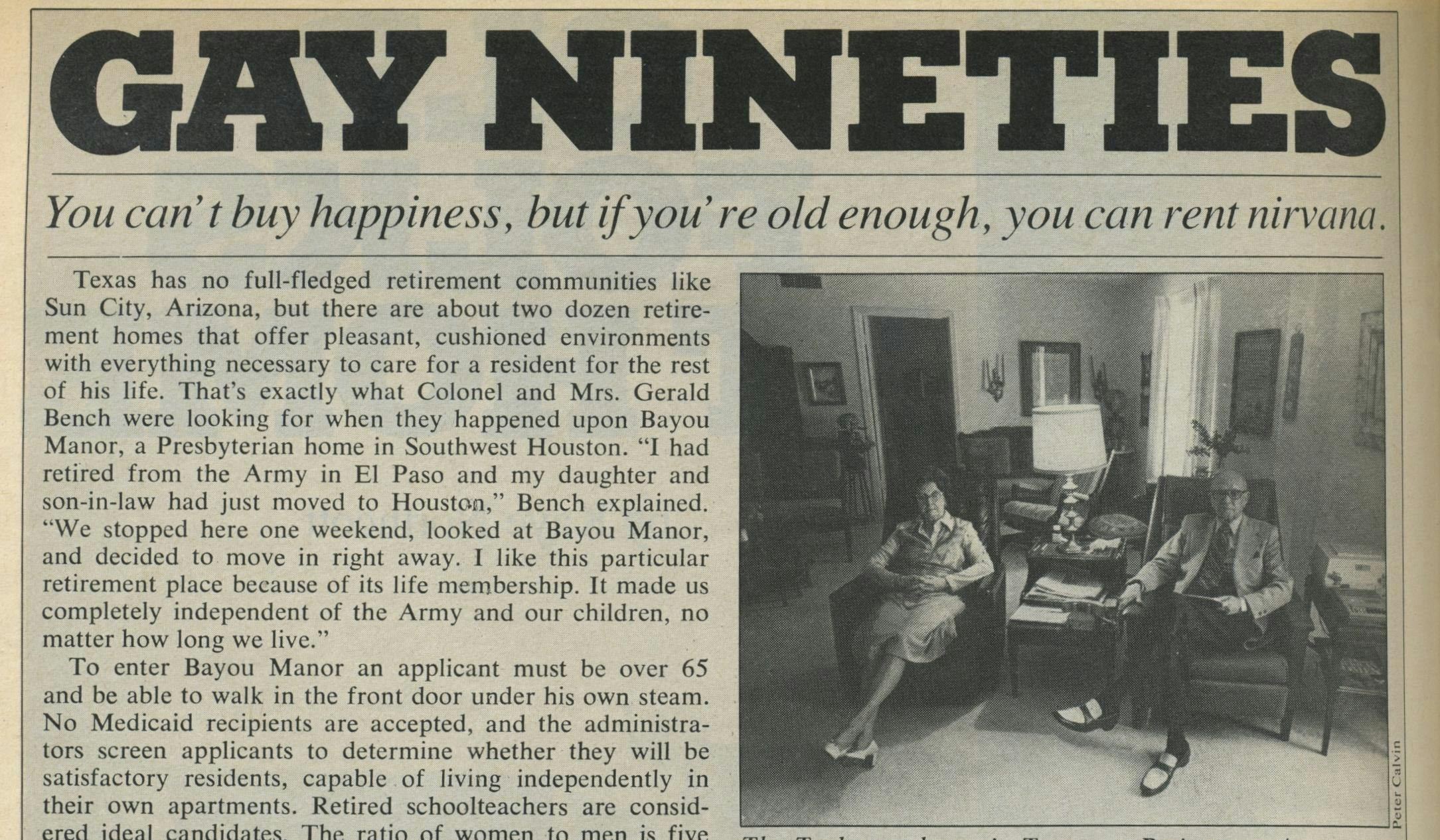

Texas has no full-fledged retirement communities like Sun City, Arizona, but there are about two dozen retirement homes that offer pleasant, cushioned environments with everything necessary to care for a resident for the rest of his life. That’s exactly what Colonel and Mrs. Gerald Bench were looking for when they happened upon Bayou Manor, a Presbyterian home in Southwest Houston. “I had retired from the Army in El Paso and my daughter and son-in-law had just moved to Houston,” Bench explained. “We stopped here one weekend, looked at Bayou Manor, and decided to move in right away. I like this particular retirement place because of its life membership. It made us completely independent of the Army and our children, no matter how long we live.”

To enter Bayou Manor an applicant must be over 65 and be able to walk in the front door under his own steam. No Medicaid recipients are accepted, and the administrators screen applicants to determine whether they will be satisfactory residents, capable of living independently in their own apartments. Retired schoolteachers are considered ideal candidates. The ratio of women to men is five to one. There is an initial “life fee,” which runs from $10,000 to $30,000 and which pays for the right to occupy an apartment at Bayou Manor for life. The occupant gets no equity in the apartment, but a refund is made if he lives there forty months or less. In addition to the life fee, Bayou Manor has a “monthly care fee,” ranging from $430 a month for a single person in a small one-room apartment to $920 for a couple in a two-bedroom garden apartment. This fee, which is subject to adjustments for inflation, pays for three meals a day, apartment maintenance, utilities, weekly maid service, treatment by Bayou Manor physicians, an unlimited number of days of nursing care in Bayou Manor’s health care center, and any outside hospitalization and surgery expenses (except for preexisting medical conditions) not covered by Medicare or insurance. The Presbyterian Church helps residents who cannot afford the entire fee. There is always a long waiting list for the larger apartments.

Other retirement homes operate on a flat rental fee. Treemont, a proprietary home with facilities similar to Bayou Manor’s, charges a minimum of $395 a month for an efficiency apartment, daily meals, utilities, maid service, and the use of the clubhouse. Double occupancy in the biggest apartment is $1200 a month. Trips to the adjacent nursing home cost extra, as much as $45.50 a day for a private corner room.

Colonel Bench, my guide at Bayou Manor, is the socially active kind of person who flourishes in a retirement home. He sets up the home’s public-address system before meetings, handles the outdoor Christmas decorations, and pins the little flags on the map that displays the birthplaces of Bayou Manor’s residents. “I’ll run your legs off,” he warned, as we set out from the visitors’ lobby on the first floor. We buzzed through the post office, the lounge where residents play cards in the evening, the carpeted dining room, the chapel and auditorium, the library, the guest rooms for visitors ($12 a night), and the resident-run convenience store. Occupants rarely have to venture outside the complex, but there is a shuttle service for people who like to visit nearby shopping centers, and some residents drive their own cars.

The Colonel ushered me out into the soupy Houston heat to admire the home’s two fine rose gardens. Gardening is by far the most popular outdoor activity at the retirement homes. Walking ranks a poor second, but a few residents try to log a mile a day, which is six and a half laps around Bayou Manor’s paved walkway.

Like all the nursing and retirement homes I visited, Bayou Manor’s apartments have special adaptations for the elderly. There are handrails in the hallways, benches by the elevators, and grab bars and raised toilets in the bathrooms. A telephone by each bed is linked to the Bayou Manor switchboard. Many homes have emergency pull cords in the bedrooms and bathrooms.

There was a cruise-ship bonhomie at Bayou Manor, much joshing and formal pleasantry in the elevators. But more than any other living situation, Bayou Manor reminded me of a college dormitory with the usual cliques, petty jealousies, and well-oiled gossip machine. I was told of the widow who fell in the elevator one morning. Although she only tore her stockings and sustained no injuries beyond a couple of bruises, the news was all over the building by the next morning. At breakfast when a friend asked her how she was doing, she answered tartly, “I feel all right and I don’t want to hear any more about it.”

In addition to visiting some of the most expensive homes, I saw three federally subsidized apartment buildings for the elderly in Dallas and Houston. Rental fees are based on one-fourth of the resident’s adjusted gross income, which is about $50 a month for someone living on a monthly Social Security check. A federal nutrition program provides hot meals at the buildings once a day for as little as a quarter a meal. The apartments are comparable to those at Bayou Manor and Treemont, except that the floors are covered with linoleum rather than carpeting. The government buildings have fewer recreational facilities and provide no health care, but they are in such great demand that some have five-year waiting periods.