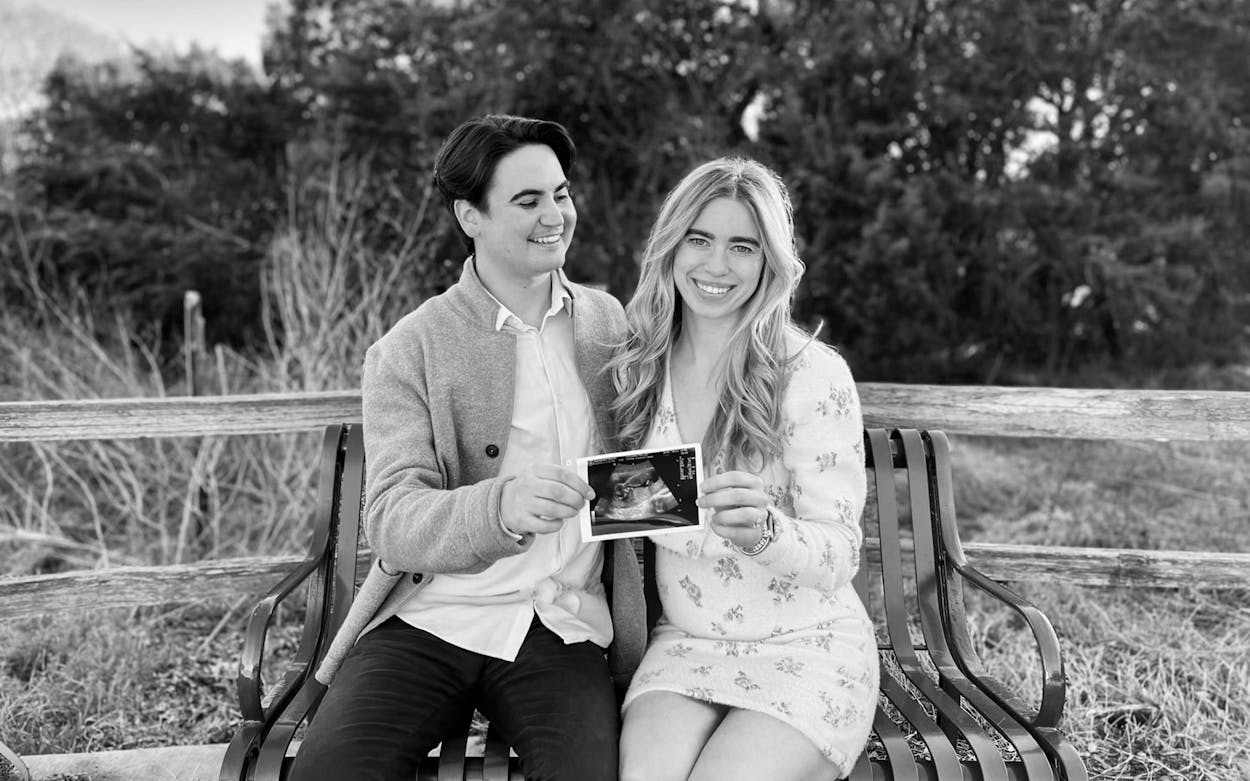

As my husband and I headed to our doctor for an anatomy scan of our baby on a Monday morning in February, we weren’t concerned. We had spent a few years trying for a baby: eighteen months of fertility treatment and three embryo transfers. We had learned to temper our optimism with caution. But this time five ultrasounds hadn’t revealed any complications. So on the day of the seventeen-week anatomy scan, we spent the ride to the clinic discussing our eighth-anniversary dinner, set for later that night, and excitedly considered posting a pregnancy announcement, along with pictures we had taken after a hike a few days earlier. We never ended up having that dinner or posting those photos. After that visit to the doctor, our lives would be forever changed.

The first half hour of our appointment was routine. An ultrasound technician dutifully counted the number of bones our baby had and pointed out her body parts as we watched her wiggle around like she had during previous ultrasounds. Seeing her growth over the weeks and watching her move around left us both in awe; we felt so much love for our baby. Then the routine broke. After the scan, a doctor walked into our exam room and asked me to get back on the ultrasound table so he could reexamine an area the technician had brought to his attention. I remember him mentioning something about the spine, but I couldn’t see it at first: my baby’s spine looked fine to me. Then, as he pointed to the base of her skull, I noticed it: a giant bubblelike structure protruding out from her back. Before my husband and I could ask questions, the doctor turned to us and said, in a straightforward manner, that our baby would not survive.

In many other states, that might have been the end of our nightmare. But in Texas, it was just beginning. After what could have been ten minutes or two hours—time has seemed to blur since then—we collected ourselves and tried to have a conversation about what came next. The doctor explained to us that our baby had an encephalocele—a defect of the neural tube—that he compared to “being struck by lightning”—a random occurrence that could not have been prevented. The prognosis, he explained, was poor in most cases, but was made even worse when portions of the brain are herniated into the encephalocele sac, as was our baby’s. She was almost certainly not going to survive outside the womb. In the unlikely event that she happened to remain alive after birth, she would live at most a few hours and be unable to breathe on her own as she died a painful death.

I asked the doctor if he was 99 percent sure he was correct on this diagnosis, and he told me he was 100 percent sure, but that we should still get a second opinion for peace of mind before doing anything. When it came to “doing anything,” however, he explained that our options would be limited. If we had been in the same situation just a few years ago, we would have been able to terminate the pregnancy for medical reasons right here in Texas with the medical team we trusted. But in the 2021 legislative session, state lawmakers passed two bills that fundamentally changed access to abortion. One, Senate Bill 8, also know as the abortion bounty law, allowed private citizens to sue anyone who helps someone obtain an abortion in Texas beyond about six weeks after gestation. The other legislation, the so-called trigger law, made abortion illegal in the state except in cases in which the life of the mother was at risk or in which there was a chance of “substantial impairment of a major bodily function,” effective one month after the Supreme Court overturned the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade decision.

By the time I was pregnant, no one in Texas was offering the procedure except in cases of medical emergencies—and even then, many providers were uncertain about which abortions qualified and were scared of potential lawsuits from state attorney general Ken Paxton. While my life was not in immediate danger and my pregnancy might not constitute an emergency under Texas law, the doctor assured me it was safer for me to get an abortion than to carry the pregnancy to term—to say nothing of the mental anguish of carrying a baby who was never going to live for another twenty weeks. Immediately after booking an appointment for a second opinion, I called a clinic in New Mexico to schedule a termination for a week later. As I researched how to get to the clinic, I felt like someone navigating the black market for illicit drugs or explosives, instead of a grieving mother accessing necessary medical care.

During our next anatomy scan, I sobbed the entire time, repeating to my baby that I loved her so much and I was so sorry. The doctor confirmed the initial diagnosis and didn’t object to our plan to terminate the pregnancy. We proceeded to sleepwalk through the remainder of the week. While our doctors treated us with compassion and provided us with useful medical information, they were limited in how much they could help us for fear of potential lawsuits. We were left on our own to research options and coordinate interstate travel while dealing with the most traumatic situation of our lives.

The following week, a few hours before we were scheduled to head to the airport, I received a call from the clinic in New Mexico that, because of a shortage of medication for the procedure, it would have to cancel. We already had all our accommodations booked and now had to scramble to find another clinic. We had to wait another week to have the procedure in Colorado. The emotional toll of waiting was compounded by the financial burden of last-minute travel changes. Because of a bill passed by the Texas Legislature in 2017, I also was not allowed to use my medical insurance for this procedure and had to pay for it out of pocket.

We spent more than $6,000 between the travel and the medical bills for something that elsewhere would have only cost us $1,000 or so—probably less with a medical co-pay. Still, we are lucky. Countless Texans in our shoes cannot afford these costs. And while abortion-rights groups in the state have raised funds to help cover travel expenses, five bills in front of state lawmakers this session would effectively outlaw such funds.

When I underwent the procedure in Colorado, I was terrified; I was nineteen weeks pregnant, and all I’ve ever heard of second-trimester abortions from Texan politicians is that they are rare and dangerous. Instead I was treated with dignity, and every medical professional respected the gravity of our situation. The abortion was a safe outpatient procedure. I was able to fly home the next day. At the Denver airport, I bought a stuffed bear and clung to it, running all the possible scenarios in my head of what would happen once we were home. I was bleeding, 24 hours post-op, and had just lost my very wanted baby, but all I could think about was being viewed as a criminal.

Of course, I’m not a criminal. I’m a mother who made the best decision she could out of love for her baby, who was terminally ill. After the passage of Senate Bill 8 last session, state leaders claimed they were putting an end to a cruel practice. Ken Paxton called abortions “barbaric,” and a press release from his office declared that the law “protects the unborn from gruesome medical procedures.” When he signed the bill, Governor Greg Abbott said he was “cultivat[ing] a culture of life.” That is not what the law does. For two weeks, after learning my desperately wanted child would not have a life, I experienced cruel emotional torture trying to access an abortion I had never wanted but desperately needed. State lawmakers legislated without knowing, or caring about, the pain they would cause.

- More About:

- Texas Lege

- Abortion