Like most folks in Kinney County, Donna Schuster recalls an era when migrants turned up on her property kindly asking for a sip of water and directions. But the rancher, who lives 25 miles from the border, says interactions with migrants have been different this year, to the point where she no longer feels safe. Back in April, as she got home one day, Schuster says she was startled by a man standing on her deck, sipping from a drink he’d taken from her outdoor refrigerator. She scared him away, she says, along with two others hiding in the brush, then called the county sheriff, who arrived after the men were gone. Schuster now packs a pistol, and has a rifle in her truck for good measure when she’s out tending to her cattle and angora sheep.

“I hear stories that they’re carrying guns, they’re carrying drugs, you know, and the trash they’re leaving, just an unbelievable amount of trash in the pastures,” Schuster tells me as we tour her ranch one day in September. “And you don’t touch the trash, because it might have fentanyl, but what if my cows eat it?”

To hear locals tell it, brazen encounters with migrants have become run-of-the-mill. “I’ve had eight break-ins, they’ve busted windows out, kicked doors in,” Cole Hill, a 32-year-old rancher who lives 35 miles from the border, tells me on a recent afternoon. Hill says he returned one night to his ranch hand’s house to find a group of migrants grilling meat outside and his car hotwired. The Kinney County sheriff came and arrested the men.

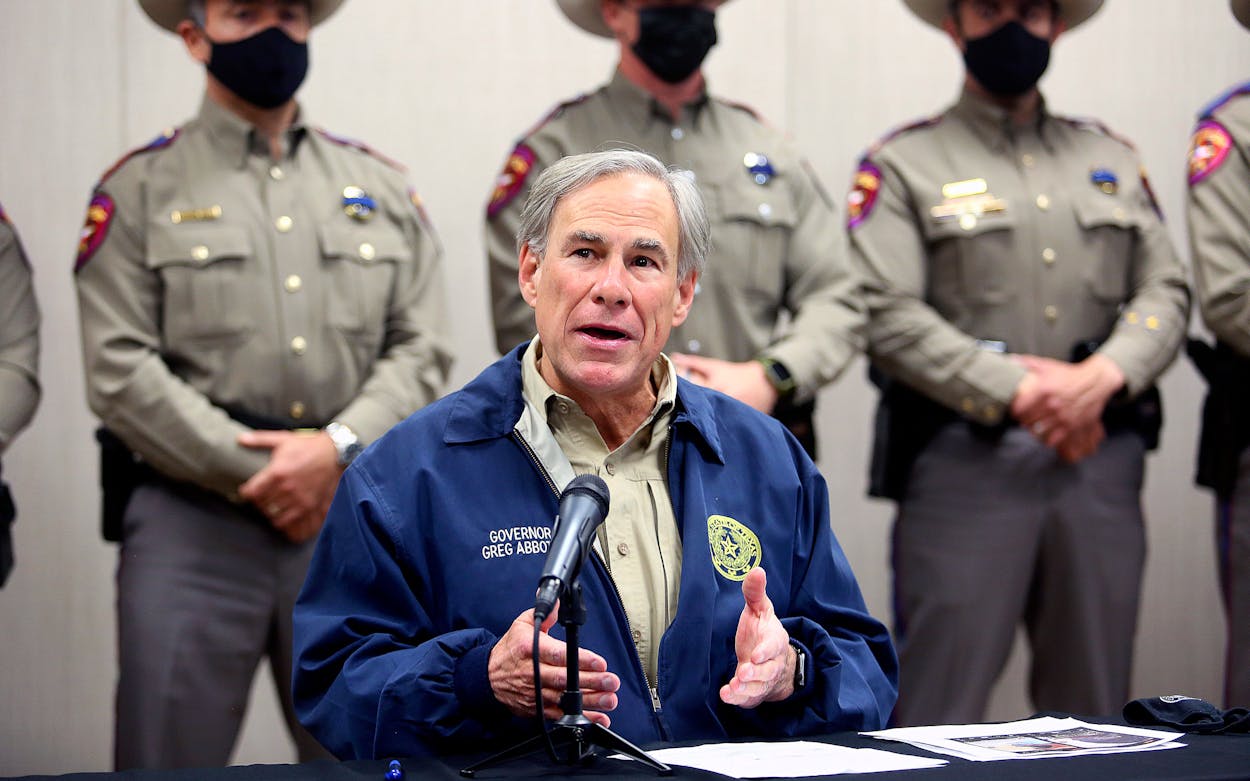

Over the past month, the border town of Del Rio, in neighboring Val Verde County, has captured headlines with the arrival of thousands of Haitian asylum seekers. But Kinney County, whose population is less than four thousand, has arrested more migrants, who’re arriving from throughout Central America, than any other county in Texas. Earlier this year, Governor Greg Abbott announced the multibillion-dollar Operation Lone Star to crack down on migrants crossing the border, deploying one thousand Department of Public Safety troopers and Texas National Guardsmen to assist federal agents in fighting the smuggling of migrants and drugs, with as many as 70 percent assigned to Val Verde and Kinney counties. Then, in the summer, he deputized state police and military to arrest migrants for trespassing charges, but he needed the cooperation of landowners to press charges, and county officials willing to take on a tsunami of prosecutions. In Kinney, more than anywhere else, Abbott found both.

With more than 1,300 arrests, overwhelmingly on misdemeanor charges, the Kinney sheriff’s office has caught more migrants, by a wide margin, than all other counties combined. Though hundreds of those apprehended have been released on bond, 792 of the 914 immigrants currently in state prison were arrested in Kinney. With few exceptions, ranchers in the county have legally empowered Brad Coe, the sheriff, who brings a cutout of Vice President Kamala Harris to press events to chastise, to arrest migrants on their properties and to act on their behalf to testify against them in court—a system that some scholars say is legally dubious. In September, Coe also appealed on social media to the hospitality of Kinney residents to put up police in need of a place to stay. He found close to one hundred willing ranchers, including Hill, who agreed to host sheriff’s deputies reassigned from Galveston to the South Texas county under Abbott’s operation.

Whether the arrests are helping ranchers, or even addressing an actual problem, is uncertain. The complaints of many locals about migrants are hyperbolic, if not outright false, and inaccurate dialogue abounds on social media. Mark Zigmond, owner of a popular barbecue restaurant in Brackettville, is convinced that migrant smugglers dine in his restaurant, an allegation based on conversations in Spanish that he overheard and described as suspicious. Worried that a high-speed chase might end in a fiery wreck on campus, the Brackettville Independent School District spent $7,000 this summer to install a series of thigh-high boulders along the grassy medians of its schools. And on a recent weekend, Coe fielded dozens of calls from terrified locals inquiring about 150,000 migrants headed straight for Kinney, based on a post on Project Camelot, a conspiracy site better known for coverage of extraterrestrials. “That was the wildest rumor over the weekend,” Coe said. “I probably had fifty people asking if it was true, if (migrants) were taking over and that shots had already been fired.”

Many in Kinney are also influenced by xenophobia, describing the influx of migrants as an “invasion” and voicing language similar to that of the “great replacement” conspiracy theory that foreigners will seize power in the U.S. through immigration and reproduction. “Biden is diffusing all of these people in our country to change our culture,” says Kinney County Judge Tully Shahan, whose office is decorated with photos of actors on the set of great Westerns filmed in Kinney, including Lonesome Dove, Streets of Laredo, and The Alamo. “The left is on the way.” Tim Ward, one of four county commissioners, tells me “these people are obviously bringing diseases. There’s leprosy, tuberculosis, measles, chicken pox, they’ve had some show polio, and COVID as well.”

And while many ranchers say they’ve encountered more migrants on their properties than in the past, claims of an influx of crime verge on the hysterical. Matt Benacci, a reporter for the weekly Kinney County Post, chalks this up in part to the fact that while the county shares a border with Mexico, no residents live along it—meaning the empathy common to towns that straddle the international line is in short supply here. “There’s no deep, abiding connection across the border,” Benacci says. Around 800 of the arrests the county has made involve trespassing misdemeanors, compared with just 160 for felony criminal mischief for cutting fences and damaging property. After parsing the crime data, Coe confessed that despite hyperbolic claims of a crime wave, the reality is different. There have been just two attempted assaults pegged to unauthorized migrants this year, and one of them involved a store owner who felt threatened when asked for a ride. Burglaries and car thefts in the county edged up slightly over last year, yet in some cases locals were to blame. “It could be part of illegal alien trafficking or it could just be local meth heads,” Coe said of criminal activity in Kinney. “It’s really a bit of both.”

One thing is certain: Because of the high number of arrests, Kinney County is now facing a self-inflicted judicial crisis. Coe said the cost of jailing migrants in Kinney, and transporting them to Del Rio, where they go before a magistrate, has cost his office in excess of $100,000, a bill he intends to send to Vice President Harris. So far, Kinney officials have filed charges against nearly one thousand migrants, with hearings scheduled for the last week of October through November and December. But for a county that hasn’t had a jury trial in seven years, according to the county clerk, the prosecutorial ambitions are wildly unrealistic. “We’ve already seen them dismissing cases,” Kathryn Dyer, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law’s criminal defense clinic, says.

As arrests pile up at a clip of several dozen per week, the task of preparing cases against hundreds of migrants also comes at a hefty price. During a typical month court costs may run $25,000, but Shahan said the expenses for cases involving migrants over the next ninety days will cost about $59,000, and estimates that, over the next two years, prosecuting at least 1,300 migrants, and perhaps thousands more, will cost nearly $5 million. In mid-October, Abbott awarded $36.4 million to fund law enforcement and prosecutions in support of Operation Lone Star, $3.19 million of which will go to Kinney.

For now, the colossal task of prosecuting 1,300 immigrants, and counting, largely falls to Brent Smith, the fresh-faced county attorney. Smith knows locals will judge his term, which began in January, by how he handles these cases. He expects he can shoulder the load. “It’s kind of like eating an elephant,” Smith, an avid hunter, says of his approach. “You take one bite at a time.” He believes if he prosecutes effectively, he can reduce crime. “At the very least I can create a deterrent so that maybe the next time they’ll go through another county.”

Yet Smith acknowledges that when it comes to trials, the prospect of Coe testifying in hundreds of cases, in place of those who directly witnessed the alleged crimes, will create headaches. “The sheriff is just standing in as a witness for the purpose of arrest, but that won’t hold up as a witness at trial,” Dyer says. “You have to have the landowner.”

Immigrant advocates and defense attorneys have already secured the release of imprisoned migrants who were not charged within the window of time the state requires. And that’s because county attorneys along the border have struggled to keep pace with caseloads that grow by the day. In late September, Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, a legal services nonprofit, secured the release of 243 migrants on personal recognizance bonds. The migrants, some of whom were arrested in Kinney, had been held in state prison without formal charges being filed within fifteen days, as required by state law for a class B misdemeanor. “We know of people who are sitting for up to two and three months in prison that haven’t been charged,” Dyer says. “It’s a complete failure of the legal system.”

As Kinney County hemorrhages money taking care of prisoners and prosecuting them, it’s unclear whether the arrests have spared ranchers—the supposed victims of trespassing crimes committed by migrants—significant financial headaches. Within three months of launching Operation Lone Star, Abbott issued a disaster declaration for nearly three dozen counties, including Kinney, encouraging landowners to report damage to the Texas Division of Emergency Management, which informs the state’s disaster assistance efforts. But by early October the agency had registered just 56 claims. Some are from Kinney County, but many ranchers I spoke with there were unaware of the TDEM reporting option, while others held out little hope that logging damages would make a difference. Still others might not actually have claims significant enough to report.

Ballpark figures of the costs ranchers say they’ve incurred range from a few thousand into the tens of thousands of dollars. One afternoon in late September, I walked Cole Hill’s property with him, as he checked a fence line for signs of damage. He spotted fresh tracks in the dirt, and a warped wire fence that he said migrants had climbed like rungs of a ladder to the neighboring property. Hill estimated his damages, and investment in preventative measures, such as security cameras, to be around $9,000, all of which he has paid out of pocket.

Later that day, as she navigated her pickup truck over the bumpy dirt roads of her ranch, Donna Schuster told me that trash cleanup, along with damages to fences and a line from a water-storage tank that supplies several pastures, could run as high as $10,000. Though she hasn’t reported damages to the state, she said she agreed to press charges against migrants caught on her property, via the sheriff, because “something needs to be done.”

This story is part of Reporting the Border, a project of the International Center for Journalists in partnership with the Border Center for Journalists and Bloggers.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott