Sandy Moore spotted them lounging in plastic chairs by the Ropers Motel pool. The husband was drinking beer, the wife sipping soda. The young woman had long, dark hair. Her full lips and olive skin, set off by a red one-piece bathing suit, gave her a slightly Mediterranean look. The slim man sported a blond crew cut and seemed about ten years older than his companion. They had checked in earlier that afternoon—July 5, 1966—scrawling their names on a registration card as Mr. and Mrs. Russell Battuon.

The single-story motor court on Highway 80, just outside the hardscrabble West Texas town of Pecos, had a Spanish tile roof, a flashy neon sign, and a steady clientele of oil-field workers and long-haul truckers. Moore, a dirty-blond fifteen-year-old from Clovis, New Mexico, was spending the summer at the motel, which her grandparents managed. She waited tables at the cafe, cleaned rooms, and worked the registration desk.

About three hours after she first saw the Battuons, Moore was in the motel office when a distraught maid rushed in and struggled to make herself understood in broken English. The maid led Moore to the pool, where she too was seized with alarm. A woman was lying facedown at the bottom of the deep end, about twelve feet underwater. No one else was around, so Moore plunged in fully clothed. She twice failed to bring the body to the surface before a motel guest, drawn by the commotion, jumped in to help. Together they managed to pull the woman up and out of the pool. It was Mrs. Battuon.

As an ambulance was summoned, Moore performed CPR. Another motel employee went to the Battuons’ room and found Russell apparently taking a nap. By the time he reached the pool, his wife was on her way to nearby Reeves County Memorial Hospital. Before heading there, Russell asked Moore for his registration card, explaining that he needed it to identify himself to police. Once she handed it over, he got into a dark-colored sedan and drove away.

At the hospital, Mrs. Battuon was pronounced dead on arrival. Russell never showed up. Reeves County Sheriff A. B. Nail issued a “Be on the Lookout” alert for the man, but the search was hampered by limited information. Without the registration card, the police didn’t know his car model or license plate number. All that was left behind in the Battuons’ room was a blouse, bra, and pair of shorts. The only Russell Battuon that the sheriff’s office could find was an active-duty Marine at Camp Lejeune, in North Carolina. The couple appeared to have been traveling under fake names.

Reeves County was too small to have its own medical examiner, so an Odessa pathologist performed the autopsy. There was a red, quarter-size abrasion above the woman’s left cheekbone, but it wasn’t determined whether that injury occurred before she died or as her body was dragged from the pool. Absent evidence of foul play, the death was ruled an accidental drowning. Nail never opened a homicide investigation. “The only thing we know that [the man] did wrong was leave without paying his motel bill,” he later told a reporter.

After the autopsy, the woman’s body was sent to the Pecos Funeral Home, where it was embalmed and kept in a back parlor for several weeks in the expectation that someone would turn up to identify it. Stories about the mysterious drowning appeared in newspapers across the country, prompting families from as far away as Kentucky and Illinois to write to the funeral home out of concern that the deceased might be a missing relation. Some of them traveled to Pecos to view the body. One couple from Odessa was certain they had found their child until the dental records failed to match.

Still, those heartbroken parents were so struck by the young woman’s resemblance to their daughter that they established the “Drowned Girl Trust Fund” to help pay for her funeral. Many Pecos residents were similarly touched by the tragedy. The funeral director donated a handsome wooden casket. A local clothing store supplied a blue polka-dot dress. Others chipped in to buy a simple headstone, which identified her as “Unknown Girl, Drowned.”

Pecos occupies a flat expanse of arid brushland on the northeastern edge of the Chihuahuan Desert in remote West Texas, not far from the New Mexico border. Founded as a cattle-drive camp in the late nineteenth century, the city hosts an annual rodeo that claims to be the world’s oldest, with roots dating back to 1883. Pecos became a regional supply hub after oil was discovered in the Permian Basin in 1920, and like that of many West Texas towns, its population rose and fell over the years in rhythm with the price of crude. In the mid-sixties, it was home to 16,000 residents—its all-time peak. It had one high school, along with two banks, five car dealerships, fourteen motels, and 24 churches.

Because nobody knew the drowned woman’s religion, her funeral service, attended by about fifty locals, was conducted by both a Catholic priest and a Protestant minister. Three sheriff’s deputies and three police officers served as pallbearers. “This girl is not known to us here, but most certainly she is known to God,” the minister told the assembled mourners. “If there is someone, somewhere, who cares for this girl, may they know she is now surrounded in love by those who care.”

The woman’s body was laid to rest in the city-owned Fairview Cemetery, across the street from Pecos High School. For years afterward, Moore would lay flowers at the grave each time she returned to town. “I’ve thought about it so much,” she recently told me by phone from her home, outside Lubbock. “Not knowing where she was from, not knowing if her family was looking for her.”

Decades passed, and it seemed as if those questions would never be answered. Then, in 2014, a strange email set off an unlikely chain of events leading to the reopening of the case. Using a combination of genetic testing and genealogical research, a team of investigators was finally able to give a name to the woman everyone had taken to calling Pecos Jane Doe—Pecos Jane, for short. As it turned out, Pecos Jane did have a family, one that had never stopped looking for her.

In 1966, however, the best clue to the woman’s identity was a message she’d inadvertently left behind. After her body arrived at the hospital, someone noticed handwriting on the sole of her right foot. Inked by a ballpoint pen were two words: “Joe” and “LEAN.”

Todd Matthews calls them “orphan cases”: bodies unidentified for so long that law enforcement has given up on them. The Department of Justice estimates that the remains of about 40,000 unidentified bodies are stored in evidence rooms or buried in graves scattered across the country, with another 4,400 discovered every year. Some are murder victims. Others met their deaths by accident or took their own lives. The longer they remain unnamed, the less attention they tend to receive from police. Often no one is advocating for them, and officers have little information to work from. “Nobody wants to take on the challenge, especially when you don’t have a family that is complaining,” Matthews said. “With an unidentified body, there’s nobody to bitch about it. They’re in the ground.”

A voluble, goateed Tennessean, Matthews has dedicated his life to solving such John and Jane Doe mysteries. He became interested in the subject after his wife told him the story of her father discovering the decomposing remains of a young woman wrapped inside a sheet of canvas alongside a Kentucky highway in 1968. (That it was a woman is unusual; the vast majority of unidentified bodies, like most homicide victims, are male.) Despite having no investigative training—at the time, he worked for a company that made automotive air conditioners—Matthews spent most of the nineties chasing down leads before successfully identifying her as Barbara Ann Hackmann Taylor, who’d gone missing from her home in Lexington, Kentucky.

One of the reasons his investigation took so long was the absence of a national clearinghouse for missing and unidentified persons. So Matthews decided to create one. In 1999 he helped launch the volunteer-run Doe Network. Dozens of amateur sleuths began compiling a list of missing persons and unidentified bodies throughout the country, scouring newspaper archives in search of forgotten cases. Each time they found one, it was entered into the organization’s online database. Soon Matthews was receiving hundreds of tips a year. The Doe Network’s list has grown to more than four thousand entries, and the group claims to have helped solve nearly a hundred cases.

Partially inspired by the Doe Network, in 2007 the Justice Department created the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. Known as NamUs, the organization enlisted the help of Matthews, who became its director of communications and outreach. As part of the job, Matthews was given administrator access to the NamUs database, which is managed by the University of North Texas Health Science Center, in Fort Worth. (UNT’s Fort Worth and Denton campuses are home to a cluster of units dedicated to forensic investigation.) Almost immediately, he started entering cases of his own, just as he had at the Doe Network. Only law enforcement agencies and medical examiners were supposed to do that, but Matthews rarely did things by the book.

In late 2014, Matthews received an email from a Hotmail account registered in the Netherlands. “There is an unidentified girl buried in Fairfield [sic] Cemetery in Pecos TX,” it read. “She isn’t on Doe Network or NamUs or anywhere, and I was wondering if she could be added?” The tipster, who went by the name “Jacy J,” directed him to several news stories about the Ropers Motel drowning. Matthews dutifully entered into NamUs all the identifying information he could glean about Pecos Jane from the contemporaneous articles.

One of the chief purposes of NamUs is to connect unidentified bodies to reports of missing persons. But no one matching Pecos Jane’s description was in NamUs. Perhaps her family didn’t know about the database. Perhaps they had long since given up on finding her. After years passed without much activity on the case, Matthews asked his colleague Mike Nance, a NamUs regional director responsible for all Texas cases, if he would take a closer look.

“That’s not the normal way NamUs works, but I had to do something,” Matthews explained. “None of these cases are conventional. There’s none of them that are normal. So I try to force them—to push to get some resolution. A lot of it is just bringing them back to living memory.”

Partly to placate Matthews, or so Matthews suspects, Nance agreed. (Nance declined to comment on the case for this story, citing departmental policy.) When Nance took another look at the entry, in 2019, he appears to have made a critical realization. Specifically, that despite the death certificate’s listing her age as “19 approx,” and witnesses including Moore guessing she’d been between 18 and 20, Pecos Jane may have been a juvenile. Armed with this new theory, Nance referred the case to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, a well-resourced nonprofit founded in 1984 by America’s Most Wanted host John Walsh.

That’s how Pecos police chief Lisa Tarango ended up fielding a call from a senior forensic case manager for NCMEC who asked her to consider renewing the search for Pecos Jane’s identity. The Ropers Motel now sits inside Pecos city limits, within Tarango’s jurisdiction. “As a mother, what bothered me was imagining how her mom felt—not knowing where your child is,” she told me about why she agreed to take the case. “That had to be just tormenting to the mother and the family. Not getting to say goodbye. Just gone.”

Christian-themed artwork and inspirational posters adorn the walls of Tarango’s spacious office in the Pecos police station, less than a ten-minute drive from where Pecos Jane died. A “Blue Lives Matter” coffee mug sat next to her computer when she and I met there in early March. Tarango’s family moved to Pecos when she was an infant, in 1969, three years after the drowning, but she’d never heard of the incident before that call from NCMEC. She earned her master’s degree in criminal justice from Sul Ross State University, in Alpine, and worked for the Fort Stockton Police Department for 22 years, rising to lieutenant investigator. Pecos hired her as its police chief in 2018..

Some in law enforcement might have considered identifying a body from a decades-old case a waste of time. Not Tarango, whose West Texas politesse—she addresses everyone as “sir” or “ma’am”—belies a steely determination. “I read some old newspaper articles that said the girl may never be identified,” she recalled. “I was like, ‘That’s a challenge. We’re going to figure this out.’ ”

She assigned the case to Corporal Felix Salcido, a Venezuelan-born naturalized citizen and eleven-year veteran of the Pecos Police Department. Salcido’s investigation immediately hit a roadblock when the Reeves County Sheriff’s Office couldn’t find its original case file. It was probably destroyed in a flood or fire, he was told, or misplaced during a move. Also missing was the autopsy report from the Odessa pathologist’s office.

Salcido realized he would have to start from scratch. At first, all he had to go on were news stories from 1966. To make sure he hadn’t missed any of those articles, Salcido paid a visit to the West of the Pecos Museum, which houses microfilm archives of the several regional newspapers that operated in the sixties. It turned out that the museum’s longtime director, Dorinda Millan, a lifelong Pecos resident and the city’s unofficial historian, knew all about the drowning. In the mid-aughts she was browsing through the newspaper archives when she came across an account of the incident.

“That motel was just a block or two from where I grew up,” Millan told me in the lobby of the museum, where she’s worked since 1976. “Kids in my neighborhood would go swimming there.” She became fascinated by the mystery, making copies of every newspaper story she could find. When Salcido showed up, she was only too happy to hand over her research, grateful that somebody was finally investigating the case.

Next, Salcido and Tarango stopped by the Pecos Funeral Home, where Pecos Jane’s body had been prepared for burial. They met with 74-year-old Pablo Carrasco, who was about to retire after working there for decades. Carrasco had been a 19-year-old funeral assistant when Pecos Jane’s body arrived in 1966. “It was real sad, because nobody knew what her name was or nothing,” he told me. “We all attended the funeral so that she could have some people to mourn for her.” Carrasco led the officers to a file cabinet in the garage out back, where they found Pecos Jane’s records. Among them were a copy of the death certificate, an inventory of burial expenses, and more than a dozen letters that the funeral home had received, including several from families of missing young women.

Also in the file were six color Polaroids of Pecos Jane on the embalming table. They show her on her back, eyes closed, her nude body covered by a white sheet. “We’re going to find out who you are,” Tarango recalled thinking when she first saw the photos. A forensic artist at NCMEC used the Polaroids to create a reconstruction of Pecos Jane’s face, which the organization posted on its website and social media accounts.

In the end, however, the newspaper stories, the funeral home file, and the Polaroids provided few tangible clues. After fruitlessly chasing leads for a few weeks, Tarango and Salcido decided that their best shot at identifying Pecos Jane was getting a sample of her DNA. That meant exhuming her body. “People have tried for more than fifty years to solve this, but nobody pushed the envelope too far,” Tarango said. “Once we got going, we were going to see it to the end.”

To conduct the exhumation, the Pecos police enlisted the services of Mark Ingraham, a veteran forensic anthropologist at the University of North Texas Center for Human Identification. I reached Ingraham via Zoom at his Denton office, which is decorated with animal skulls he’s collected in the course of his career. Three or four times a year, Ingraham is called upon by some Texas law enforcement agency to dig up a body, typically a murder victim buried in a clandestine grave. Cemetery exhumations are less common. Unidentified bodies are often consigned to unmarked pauper’s graves, but with Pecos Jane the police knew exactly where to dig. Of all the kindnesses shown by the people of Pecos to the unknown woman, the gift of a proper headstone may have been the most significant.

Just before dawn on August 27, 2019, Ingraham, Tarango, Salcido, and Carrasco gathered at Pecos Jane’s grave at Fairview Cemetery. As they looked on, a backhoe operator began digging away at the dry caliche soil, gouging a rectangular cavity in the earth. Once the hole was around six feet deep, the backhoe shovel hit the wooden coffin. Ingraham climbed down into the grave to get a better look. After more than five decades underground, the coffin had mostly disintegrated, but the skeletal remains were in good shape. Mixed among the bones, which had been dyed a reddish-tan color by the soil, were scraps of pantyhose and a blue polka-dot dress.

Using a trowel and a brush, Ingraham carefully removed the dirt from each of the bones and transferred them onto a clean white sheet he had spread out by the edge of the grave. They were laid out there in proper anatomical position. Once the entire skeleton had been exhumed, all of it was wrapped in paper, placed inside a blue body bag, sealed in a box, and sent off for DNA testing.

Nearly a year later, a FedEx courier dropped off a small package at the bucolic campus of Othram, a private forensic laboratory in the Woodlands, the master-planned community north of Houston. Inside the package was a molar taken from the jaw of Pecos Jane. Othram—the name means “city wall” in one of the elvish dialects invented by J. R. R. Tolkien for The Lord of the Rings—was founded in 2018 by David Mittelman, a scientist and entrepreneur who first became interested in genomics while working as an undergraduate research assistant on the final stages of the Human Genome Project, the thirteen-year, $3 billion effort that paved the way for modern genetic testing.

After earning a doctorate in molecular biophysics from Baylor College of Medicine, Mittelman worked as chief scientific officer at a number of genomics companies in Texas before striking out on his own with Othram, which bills itself as the only private DNA lab in North America dedicated to advanced forensic investigation. Over its three years of operation, the lab has performed DNA analysis for law enforcement agencies across the country, as well as nonprofits such as NCMEC. Last year, Othram helped the Fort Worth Police Department finger a suspect in the 1974 murder of seventeen-year-old Carla Walker, and it played a role in identifying the remains of a Florida hiker known as “Mostly Harmless.” In May 2020, Othram case manager Michael Vogen was browsing the roughly seven hundred unidentified bodies listed in NCMEC’s online database, looking for cases the lab might assist with, when he came across Pecos Jane.

After the 2019 exhumation, the remains went to Ingraham’s lab, in Denton, where a forensic examiner determined that the skeleton belonged to a white woman between the ages of fifteen and eighteen. A bone fragment was then sent to Fort Worth, where another UNT forensic analyst extracted a DNA sample and uploaded it to the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, a national database of genetic profiles submitted by law enforcement agencies. Pecos Jane’s DNA didn’t get any hits—not surprising, given that the database was established in the nineties, decades after her death.

The investigation appeared to have reached another dead end. Then, out of the blue, Tarango received a call from Othram. Vogen offered the lab’s services, telling her that the case could probably only be solved through forensic genetic genealogy, a relatively new investigative method that combines advanced DNA analysis with traditional genealogical research. Since 2007, when 23andMe released the first high-profile direct-to-consumer DNA test, millions across the world have submitted swabs of saliva to one of a steadily multiplying number of testing companies. Some of them submit DNA to learn about their ethnic backgrounds; others want to calculate their risks for various medical conditions. Once users receive their test results, many upload them to third-party websites, such as GEDMatch, which maintain massive DNA databases that allow users to search for distant relatives.

Among the first to make use of these public genetic databases were adoptees searching for their birth parents. The sites also became popular with genealogists, who were able to locate hundreds or even thousands of relations based on similarities in DNA. It wasn’t long before law enforcement agencies realized they might use these same databases to identify criminals. By uploading a sample of DNA taken from a crime scene, investigators could construct a family tree for their suspect, leading them, in many cases, directly to their target. In one famous example, in 2018, detectives in California used DNA from an old rape kit to identify Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. as the Golden State Killer, a serial murderer and rapist who had eluded police since the seventies.

Police also began using the genetic databases to identify dead bodies, a process whose success depends on the integrity of the recovered DNA. “If I swab your mouth, that’s clean—low-contamination, beautiful, high-quality, high-quantity DNA,” Mittelman explained while giving me a tour of Othram in April. Wearing a rumpled T-shirt, jeans, and unlaced sneakers, the boyish forty-year-old scientist told me that DNA degrades over time and can be contaminated by nonhuman sources of DNA, including bacteria.

After scrubbing such contaminants from the DNA taken from Pecos Jane’s molar, Othram “read” the sample’s genetic sequence using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000. The washing machine–size device costs about $1 million and can map an entire human genome—a process that once took years—in a matter of days. From the NovaSeq data, the Othram team identified hundreds of thousands of Pecos Jane’s genetic variants, random changes in her genetic code that had been passed down through generations of her ancestors. Most of those variants, also known as single-nucleotide polymorphisms, occur in sections of DNA that don’t serve any identifiable biological function. Such variations are extremely useful in genetic genealogy, because they can be used to determine how closely two people are related.

Othram uploaded Pecos Jane’s sequenced genetic data to two public genealogy websites, FamilyTreeDNA and GEDMatch. Following the publicity surrounding the Golden State Killer case, many genealogy websites, respectful of some customers’ privacy concerns, enacted policies barring law enforcement agencies from their databases. FamilyTreeDNA and GEDMatch still grant police access, but only to the data of users who opt in to forensic investigative searches. Fortunately for Othram and the Pecos police, those companies boast roughly a million users each.

Last November, under an arrangement brokered by NCMEC, Othram handed off the Pecos Jane case to Innovative Forensic Investigations, in the small town of Emporia, Virginia, near the North Carolina border. The company was founded in 2019 by private investigator Jennifer Moore. Like many forensic genetic genealogists, Moore is self-taught; her introduction to the field came when she helped her husband track down his biological parents.

FamilyTreeDNA’s search algorithm turned up the best match for Pecos Jane’s DNA profile: a set of three siblings living in Texas. The percentage of shared genetic variants suggested that the siblings were the great-grandchildren of one of Pecos Jane’s first cousins. Born long after Pecos Jane’s death, they had likely never heard of their distant relative. Nor could they have known that uploading their DNA to a public website might help solve a decades-old cold case. (For privacy reasons, Moore declined to provide their names.)

Starting from those three Texas siblings, Moore’s team used traditional genealogical tools to trace their family tree up to the common pair of ancestors they likely shared with Pecos Jane. Then the investigators painstakingly followed the tree back down, one branch at a time, looking for someone who would have been Pecos Jane’s approximate age at the time of her drowning. After several weeks of work, they homed in on a Kansas family of fifteen children. Ten were still alive, and several had accounts on Facebook, which has become an invaluable resource for genealogists. Browsing those accounts, the team discovered that one sibling had been posting regularly about a sister who’d gone missing many years earlier.

A few weeks later, 74-year-old retiree Joyce Hemmy received a knock on the door of her trailer in the FairHaven Mobile Home Park in St. Petersburg, Florida. Outside was a cold-case detective from the St. Petersburg Police Department. The detective explained that he was there on behalf of the police in Pecos, Texas. Did she, by any chance, have a missing person in her family?

Joyce Hemmy started to sob.

Jolaine Hemmy grew up on a 160-acre farm outside the town of Salina, in central Kansas. The ninth of fifteen children born to Richard and Elverda Hemmy, she had a typical farming childhood, waking early each morning before school to help the family with chores. “The boys would help take care of the cattle, run the tractors,” her older brother Paul told me by phone from Salina, where he still lives. “The girls had the choice of cleaning the house or cooking. My mom was an excellent cook, and so were all the girls.”

The large Catholic family grew wheat and raised chickens, pigs, turkeys, and Angus cattle. Between their livestock and a large vegetable garden, the family was well provisioned; the six siblings I spoke to for this story fondly remembered big dinners. On weekends the Hemmys would sometimes picnic at nearby Kanopolis Lake, although the children mostly stayed out of the water. Many of them, including Jolaine, couldn’t swim.

The percentage of shared genetic variants suggested three siblings in Texas were the great-grandchildren of one of Pecos Jane’s first cousins.

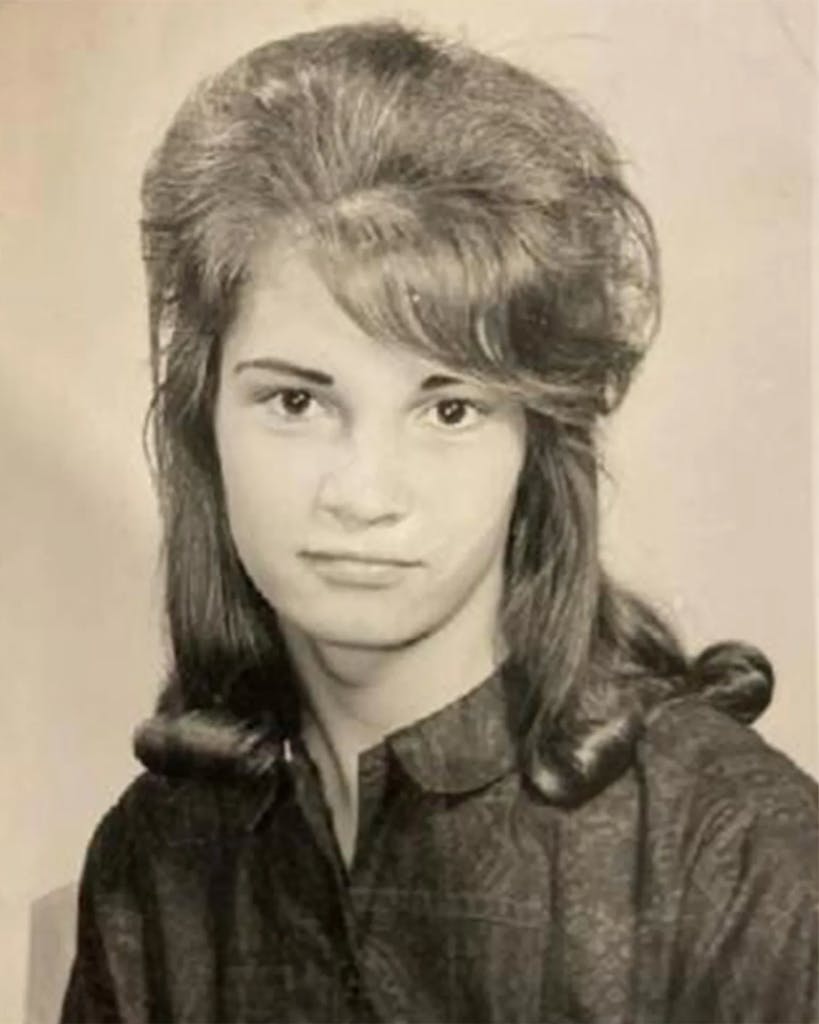

Rosemary, the eldest daughter, remembered Jolaine as an unusually quiet girl. “She was very, very shy,” she told me. “Never had a boyfriend that we knew of.” When company came over, Jolaine would go off by herself with a book rather than join in the conversation. She was closest to her sister Joyce, who was just fourteen months older. “They did everything together,” recalled Jolaine’s younger sister Marilyn. Two high school yearbook photos released by the family show Jolaine as a striking girl with a thoughtful, somewhat sad expression.

Shortly after graduating from Salina High School in May 1966, Jolaine moved to Kansas City. Her older sisters Joyce and Carolyn already lived there, in houses only a few minutes apart, and Jolaine divided her time between them. She waitressed on weekdays at Dale’s Drive-In restaurant and on weekends at the Nu-Way Drive-In. She told Joyce she was saving money to buy her own house, or a car, or maybe go to school, and that she wanted to become a secretary.

Sometime that summer, Jolaine met an older man while at work. Her siblings don’t remember his name, but Joyce, who met him a few times, guessed he was in his late twenties—perhaps a decade older than Jolaine. Joyce took an instant dislike to him. “He wasn’t nice to her,” she told me. “He was controlling. I told her she ought to find somebody else, but she said she liked him. I said, ‘Well, he doesn’t treat you very good.’ And she said, ‘That’s probably because I don’t do exactly what he wants.’ ”

On Friday, July 1, 1966, Jolaine stopped by Joyce’s house after work to invite her to see a movie with her, her boyfriend, and another girl. Joyce declined, explaining that she had plans to go fishing with her own boyfriend. That night Jolaine didn’t come home to either sister’s house. She didn’t return the next day, or the day after that either. “Me and my sister looked all over,” Joyce said. “We went to her work. We went to the police. We went to her girlfriends.”

Joyce and Carolyn learned that Jolaine’s boyfriend was also missing and that Jolaine hadn’t picked up her weekly paychecks from either of her employers that Friday. When they visited a police station to file a missing persons report, they were advised that Jolaine and her boyfriend had probably run off and would likely come home soon. Evidence that seemed to support that theory arrived in Joyce’s mailbox a few days later—a postcard stamped July 3 in Las Vegas. The front of the card featured a photograph of the swimming pool at the Flamingo Hotel. On the back, written in longhand, was a cryptic note:

Joyce,

Well, I got lost. See you in a couple weeks, maybe.

Jo

Joyce was immediately suspicious. The note didn’t appear to be in Jolaine’s handwriting, and her sister didn’t go by “Jo.” Jolaine’s mother, Elverda, received a letter with a similar message at about the same time. She showed it to her children, who agreed that Jolaine couldn’t have written it. Furious, Elverda tore the letter up and threw the pieces away. In Kansas City, Joyce and Carolyn began putting up flyers around town asking if anyone had seen their sister.

The letter and postcard from Las Vegas are the only clues to Jolaine’s itinerary between leaving Kansas City on July 1 and checking into the Ropers Motel on July 5. Tarango believes that Jolaine’s boyfriend may have sent both. Investigators have speculated that the couple could have eloped to Las Vegas to get married, but a check of Nevada marriage licenses for 1966 turned up nothing.

The police remain stumped about how the couple ended up in Pecos. The city seems an unlikely destination unless the man had some connection to its famed rodeo, which ran July 1 to 4 that year. A search of the rodeo records found no Russell Battuon among the 1966 contestants.

Several Hemmy family members believe he murdered Jolaine. They point out that she couldn’t swim. What was she doing in a pool?

Tarango and Salcido have also puzzled over the writing on the bottom of Jolaine’s foot, a detail that was reported in the Pecos Independent-News three days after the drowning. According to the article, “Joe” was written in longhand and “LEAN” in capital letters. The family pronounced her name “Jo-lane,” although Joyce recalled that some friends pronounced it “Jo-lean.” Maybe Jolaine was simply writing a variant of her own name, unaware that law officers would ponder its significance half a century later? Or was it, in fact, a clue to something more? Was Joe the name of her traveling companion? Was “JoeLEAN” a playful portmanteau, à la celebrity couples Brangelina and Bennifer? “We went back and forth, trying to think, ‘What is that?’ ” Tarango said. “You know, she was seventeen at the time. Was that a goofy kid thing?”

We now know that only four days elapsed between Jolaine’s disappearance and her death. If her body had been found today, Pecos police would be able to check it against missing persons reports in NamUs. But in 1966 no such database existed. The Hemmys appear never to have seen the nationally syndicated newspaper stories that prompted so many other parents to write to the Pecos Funeral Home.

So Jolaine’s family kept searching. They hired a private detective, but couldn’t afford to keep him on the case for long. As weeks turned into months and months into years, the tragedy wore away at them. Elverda was especially affected, according to her son Paul. “She would always ask us, ‘Do you think she’ll come home this year? Do you think she’s being held captive somewhere? Do you think she’s dead?’ ” he said. “She went on for probably thirty years thinking she was alive.”

Elverda passed away in 2000. On her deathbed, she told her children that she could see Jolaine in heaven and was looking forward to joining her. Jolaine’s father, Richard, died ten years later, at the age of 101. His daughter Marilyn remembers sitting with him on his porch in Salina in his later years, speculating about Jolaine’s disappearance. “I just wonder what happened to her,” he said. “I’ve always wondered.”

In January, Tarango and Salcido flew to Kansas to formally present the results of their investigation to the Hemmys. About fifteen family members gathered at the Salina home of Rosemary, the eldest daughter. Others joined via Zoom. The Hemmys listened as Tarango told the story of Jolaine’s drowning, her funeral, the inconclusive original investigation, and the events that led to the case being reopened. “It brought back a lot of memories,” her brother Bill said. “Hearing that she died that way—I mean, you kind of relive it.”

Several of the siblings expressed relief at finally knowing what happened to their sister. “I knew that she wouldn’t stay away from us,” Rosemary told me. She was glad to know that Jolaine hadn’t spent all those decades “lying in a ditch somewhere, or thrown away.”

The biggest lingering mystery in the case is the identity of the man who was with her at the Ropers Motel. If he’s still alive, he’s likely in his eighties. Several of the Hemmy family members I spoke with believe he murdered Jolaine. They point out that she couldn’t swim. What was she doing in a pool? Then there’s the abrasion on the side of her head. Sandy Moore, the motel owners’ granddaughter, recalls seeing broken glass around the pool when she pulled the body out. Could the man have smashed his beer bottle against Jolaine’s head during a fight, then pushed her into the water? In that case, though, why would he return to his room rather than immediately flee the scene? Perhaps he wasn’t responsible for her accidental death, but simply panicked and decided to disappear after learning she had drowned.

Whether or not he killed Jolaine, his decades of silence seem an act of extraordinary cruelty. At some point in the past 55 years, he surely could have dropped an anonymous note letting the family know what happened or at least where to look for her. Instead it was left to some unknown tipster with an apparent interest in obscure cold cases to reignite the search for Pecos Jane’s identity. Were it not for “Jacy J,” the mystery might never have been solved. (Matthews had heard from the account once before, and he received a message from “Jacy J” about a third case in 2015, but he has gotten nothing since. An email I sent to the Hotmail address was returned with a message saying the account was no longer active.)

Tarango and Salcido are still looking for the man who abandoned Jolaine to an anonymous burial far from her childhood home. But they hold out little hope of finding him. Even if they do, a criminal prosecution is unlikely because of the missing case file and the pathologist’s ruling that Jolaine’s death was an accidental drowning. “Can I ever prove that she was killed?” Tarango said. “Probably not.”

Sandy Moore thinks often about the day she pulled Jolaine’s body out of the motel pool, the day before she turned 16. Now a 71-year-old known by her married name, Sandy Massey, she still feels guilty about being tricked into handing over the registration card. “That has bothered me all these years,” she told me. “I blew that one real good.” She recently spoke by phone with some of the Hemmy siblings, who thanked her for trying to save their sister’s life and invited her to visit them in Kansas.

Todd Matthews was fired from NamUs last year, supposedly for his “inability to generate unique marketing content,” though he believes it was because he kept butting heads with the organization’s bureaucracy. (NamUs, which declined to comment on Matthews’s firing, is in the middle of a shake-up. The Justice Department recently announced plans to transfer responsibility for its programs from UNT to a North Carolina–based consortium that includes nonprofits and universities.) Matthews has continued his work with the Doe Network and is developing a podcast with actor Morgan Freeman’s production company. He remains obsessed with identifying John and Jane Does across the country. “I’ve had people say, ‘Well, they’re gone. What does it matter?’ It does matter,” he said. For the loved ones, “missing can be worse than dead.”

Since 2018, when the Golden State Killer case first brought widespread attention to the method, forensic genetic genealogy has become more popular with law enforcement. It has been used to solve scores of cold cases across the country, including ones involving murders, sexual assaults, and long-unidentified bodies. The Department of Defense is considering using forensic genetic genealogy to identify the remains of unknown soldiers. “I try to stay on top of the forensic side of policing, but this has been an absolute eye-opener to me,” Tarango said. “I think this is the future of policing.”

Demand for the technique is great. The DOJ estimates there are roughly 250,000 unsolved murders on the books among the nation’s law enforcement agencies, in addition to the country’s 40,000 unidentified bodies. For Texas alone, nearly 1,700 unidentified bodies are listed in NamUs, with about 60 new entries so far this year. DNA analysis costs roughly $2,500 a sample but is getting cheaper as technology improves. Civil liberties advocates remain worried about law enforcement access to massive genetic databases, such as GEDMatch—which could affect the privacy of all Americans, from genealogy hobbyists to suspected offenders—but users continue to voluntarily upload their DNA profiles.

At Othram, David Mittelman is building his own database dedicated solely to forensic investigations. Anyone can share their DNA with Mittelman’s DNASolves.com, in hopes of helping law enforcement catch, or identify, one of their relatives. Mittelman also uses the website to raise funds to support some Othram investigations. Last year, he collected $700 for the Pecos Jane case. “Viewed through the lens of 2021, using forensic genetic genealogy to solve cases seems like a novelty, a lucky break,” he recently told me. “A few years from now, it will be the standard.”

The Ropers Motel is still in operation, under new management, although its best days seem far behind it. When I visited in March, a few cars sat in the parking lot, the office was locked, and no one answered the phone. (I called again later, and a man who would only identify himself as the owner explained that he has 37 properties and can’t always be there.) The swimming pool where Jolaine drowned was long ago filled in with dirt and broken chunks of concrete, a slag heap from which sickly yellow weeds have sprouted. Only a stainless-steel pool ladder remains, half buried in the detritus.

A short drive away is Fairview Cemetery, where Jolaine was buried for 53 years. Her plot is outlined by a border of white lace staked into the bare ground with solar lamps. Candles, small stones, and plastic bouquets surround the headstone, which reads, “Unknown Girl, Drowned, July 5, 1966.” Well-wishers have been leaving mementos at the grave for years, long before the case was reopened. “When people visit their own relatives at the cemetery, sometimes they bring Jolaine flowers as well,” said Millan, the director of the West of the Pecos Museum. “The town pretty much adopted her.”

Jolaine’s remains are being held in a climate-controlled evidence room at the Pecos police station. Once the bureaucratic hurdle of getting the state to issue a new death certificate is overcome, she will be cremated by an Odessa mortuary. Her family will bury her ashes in Salina, near the graves of her mother and father. First, though, some of the remaining Hemmy siblings plan to visit Pecos to retrieve Jolaine’s ashes and visit Fairview Cemetery. “The people down there treated her so well,” Rosemary’s husband, David Divilbiss, told me. “It’s just unbelievable that the town took such an interest in her.”

In a place populated both by older residents who remember the drowning and by younger folks who learned about it only recently from the news, the Hemmys are likely to receive a warm welcome. Jolaine’s tragic death has woven itself into the fabric of the small West Texas community.

“It’s hard to let her go,” Tarango admitted. “She’s part of Pecos.”

This article originally published on June 14, 2021. It appeared in the August issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Death and Rebirth of Pecos Jane.” Subscribe today.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Sandy Moore’s grandparents owned the Ropers Motel in 1966. They only managed the property.